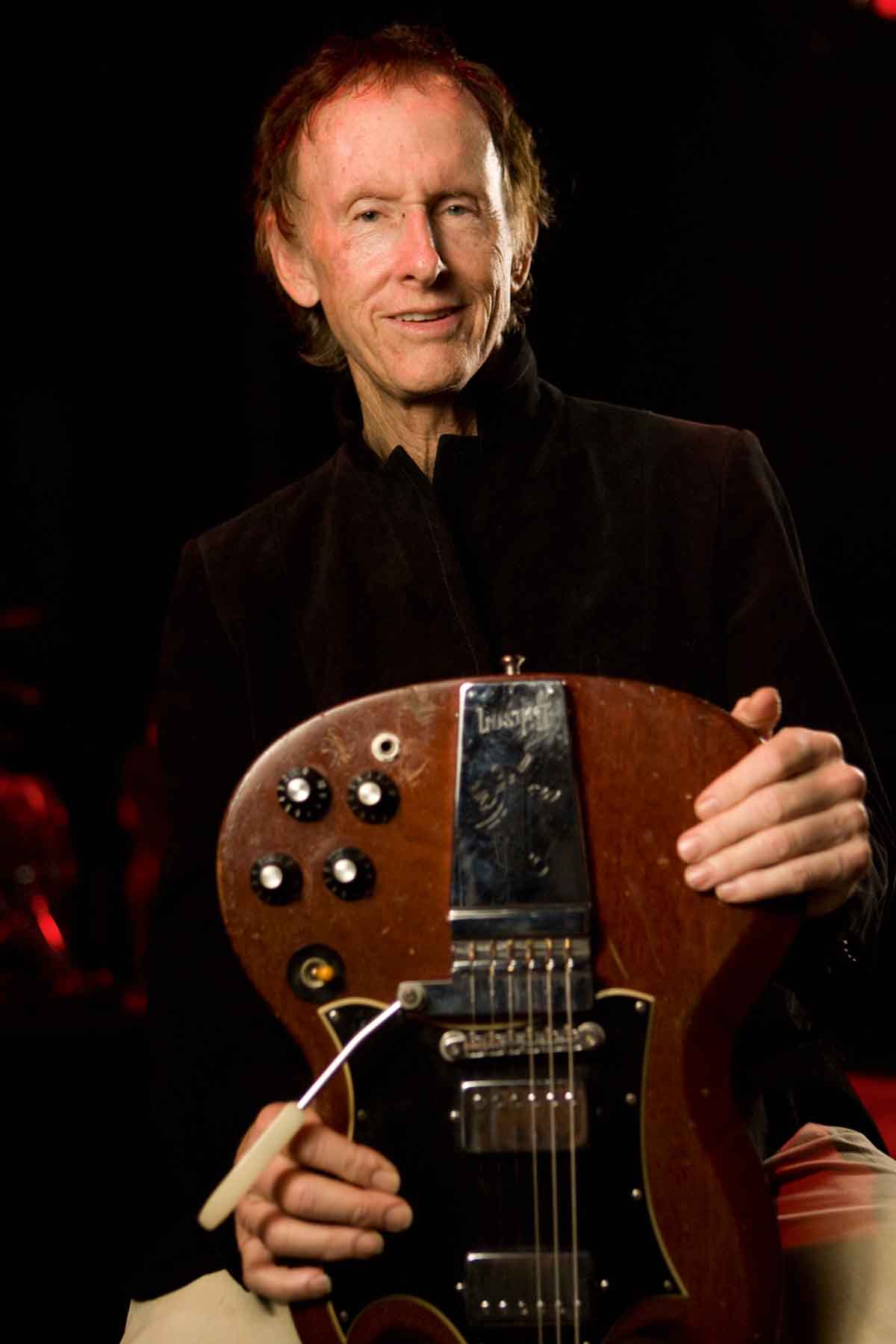

Robby Krieger: “In the Doors’ music there are a lot of silences. We weren’t the type of band that had to fill up every little gap“

The ex-Doors man on developing his style, free-form sensibility and how it was jazz informing the band all along

The Doors were many things. They played rock. They played jazz. They played blues, too. And the LA group’s charismatic singer Jim Morrison, inheriting the Beat Generation’s countercultural posture, wrote poetic lyrics oscillating between the psychonautic free-lovin’ spirit of the '60s and a foreshadowing of the darkness that would consume that decade’s end.

There was light and shade in The Doors’ sound. There were psychedelic pop hooks, proto-funk rhythms, morbid visions, sex and death.

As a guitar player, Robby Krieger pushed the envelope. He developed a hybrid jazz-blues style, was red-hot with a slide, and had flamenco chops gleaned from lessons with the late theatre actor Frank Chin.

The only one I had was a fuzz pedal, which was a Gibson [FZ-1 Maestro] fuzz pedal. I used it live more. In those days you couldn’t rely on effects to do much

This flamenco hot sauce often found itself spicing up The Doors’ compositions because... well, why not? There was an element of chance to The Doors’ writing and no rules, a dynamic that felt entirely in keeping with an era riven with chaos - when everything was up for grabs.

The escalating war in Vietnam, the assassination of Martin Luther King, the Manson Family murders; The Doors’ discography came together as America’s social fabric came apart.

Of course the '60s cataclysmic denouement would take its toll on The Doors. Morrison’s drinking worsened with a thunderhead of external crises gathering overhead – sex and death in life and in verse. Yet their songwriting lost little of its prescience in charting the emotional cadences of the decade’s bloom and ultimate rot.

But, perhaps most of all, The Doors were a state of mind. Taking their name from Aldous Huxley’s 1954 hallucinatory observations from his experiments with mescaline, The Doors Of Perception, how could they be anything else?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

As Robby Krieger tells it over the soft clipping of a lo-fi Skype line, the expansion of their minds – chemically, musically and otherwise – was a crucial staging post in The Doors’ evolution.

With the acid and the marijuana, I know it really helped Jim to write songs

Krieger is going to be telling us about his new album, The Ritual Begins At Sundown, a work of freewheeling instrumentals written and recorded with his old friend and Frank Zappa collaborator Arthur Barrow, among others, but all in good time, because the story of The Doors’ sound and Krieger’s guitar methodology is inextricably linked.

And so, back to the mid-'60s and mind-altering creative epiphanies, as Krieger, drummer John Densmore and keyboard player Ray Manzarek bonded over an interest in transcendence, and finding a natural alternative to LSD...

Perhaps it was kismet that such a headspace would draw three acid freaks together for an audience with the father of Transcendental Meditation and The Beatles’ spiritual consigliere, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.

As Krieger recalls, chuckling: “John and Ray and I had taken acid quite a bit before The Doors. I think we had taken too much acid, so we were looking for something different!

“And that’s how the three of us really met, in a meditation meeting the first time the Maharishi came to LA. It was at my friend’s house and it just so happened that three out of the four Doors were at that meeting.”

The fourth Door, meanwhile, was beating his own path to transcendence, and it was a route familiar to Krieger.

“Jim was just getting into acid at the time,” says Krieger. “He was all excited about it, and it was great because it kept him from getting drunk which was his normal thing in college, and which I don’t think helped his creativity or anybody else’s that much.”

Like Manzarek, Morrison was a graduate from UCLA film school. Both studied under the likes of Josef von Sternberg, viewed cutting avant-garde films and pursued a bohemian lifestyle. Dropping acid and smoking pot helped Morrison dial in his mojo.

“With the acid and the marijuana, I know it really helped him to write songs,” says Krieger, “because the first five or six songs that he wrote, Jim was living at a friend’s and was on a rooftop, and he smoked this Acapulco Gold and he said it was like a concert playing inside his head and all he had to do was write it down.”

Ideas came easy. By 1966, the Doors had residencies at the London Fog and Whisky a Go Go, workshopping their sound onstage. If there was freedom in how The Doors shared ideas, there were practical considerations to work around.

The likes of Doug Lubahn, Harvey Brooks and Lonnie Mack would become studio pinch-hitters on bass, but, live and when writing, Krieger and Manzarek had to fill the space in the mix. Manzarek used his Fender Rhodes Piano Bass.

Krieger, for his part, adjusted his playing style accordingly. “We never really planned it or talked about it much,” he says. “It just kinda happened. That was really where I developed my style, because we didn’t have a bass player.

“So Ray would play left hand on the piano bass, and because of that it would make him play a certain way with his right hand, and it would make me play a certain way, too. And Densmore. It was just a very odd group of musicians who came together but the results were pretty good.”

In a taste of things to come, Morrison’s confrontational presence got the band fired from the Whisky, his Oedipal ad-libs while performing The End were considered beyond the pale. But The Doors were going places, signing with Elektra in 1966 and entering Sunset Sound to record their eponymous debut.

Paul A. Rothchild was hired as producer, Bruce Botnick as engineer. Krieger couldn’t have been happier.

“We loved Paul,” says Krieger. “When I learned that he was going to produce us, I was really excited. I thought that was amazing. In fact, he was my favorite producer way from before The Doors, because I had been listening to the stuff he produced when I was in high school, like the Paul Butterfield Band, the Even Dozen Jug Band and there was an album called The Blues Project that he did with all kinds of cool and unknown players – at least to us on the west coast.

“He was from Boston. It was a whole different scene going on there. When I was at Menlo School, this private school up in Menlo Park [in San Francisco Bay Area], a lot of the kids were from back east and they brought all of this music that I had never even dreamed about.

“A lot of it was produced by Paul. He really did help us on the first three or four albums because we had never recorded before. He taught us a lot. By the time we did [1971 album] LA Woman, we all knew how to produce a record, pretty much.”

In the studio, recording the debut album, there were tantrums and magic. Having been distracted by its glow while tracking Light My Fire, Jim Morrison launched a TV set at the control room window, ending Botnick’s chances of sneaking a peak at the LA Dodgers game between takes.

On another occasion, Morrison nearly destroyed the studio with a fire extinguisher after a bad trip. But the music was coming together. Krieger had few options when it came to choosing stompboxes to place between his guitar and his trusty Fender Twin Reverb, but that sort of restriction can be liberating, and besides, Sunset had some good stuff on-site.

“The only one I had was a fuzz pedal, which was a Gibson [FZ-1 Maestro] fuzz pedal, the first one they had,” says Krieger. “Yeah, it was pretty good but I didn’t really use it that much, especially for recording. I used it live more. But, yeah, in those days you couldn’t rely on effects to do much.”

Krieger did make full use of Sunset Sounds’ echo chamber. “We had this great echo chamber for the first two or three albums,” he says. “It was a real room, and it had the hard walls. You’d put a microphone in there and it made an echo.

“Some were better than others. Up at Capitol, they had some really great ones, too. But this one at Sunset was really a nice sounding echo. If you go back and listen to that first record, I might have overdone it on the echo! [Laughs] But it was so nice. We couldn’t help ourselves.”

There were dynamics, which you don’t tend to find today at all. That was a jazz thing. People who really listen to each other when they play more than just shredding

When the album was wrapped, The End, the most debauched epic of the '60s, had made it onto the record. Butnick’s TV was swept up and Light My Fire was completed, becoming the Doors’ biggest hit. The Doors were established.

With Krieger’s unorthodox phrasing trading classical and Muddy Waters licks with Manzarak’s Vox Continental, Densmore’s touch-sensitive drumming and Morrison’s total conviction as the poet-singer, there was no band like the Doors.

What can we learn from them? What did Krieger learn? Maybe the biggest lesson is you’ve got to listen, you’ve got to give your songs space to breathe.

“Well, if you notice in the Doors’ music there are a lot of silences,” he explains. “We weren’t the type of band that had to fill up every little gap. Not only that, there were dynamics, which you don’t tend to find today at all. That was a jazz thing. People who really listen to each other when they play more than just shredding.”

Much of the Doors was a ‘jazz thing’. Krieger and Densmore – a high-school jazz band alumnus – would hit jazz clubs and immerse themselves in it. It opened Krieger’s mind to the potential of in-the-moment composition. Jazz seemed to count out infinite possibilities.

“It was definitely a factor in our music. Definitely,” says Krieger. “If you listen to Light My Fire, that part in the middle, the instrumental part, that was inspired by Coltrane’s My Favorite Things. It is the same chord structure.”

And it has so many chord changes. “When I wrote that, I said to myself, ‘Okay, I’m going to put every chord I know into this song! [Laughs] So yeah, the way it starts off, I think there’s seven chords just in that intro. G to D to F to Bb, Eb, Ab, A. People don’t realise how many chords are in that song.”

Jazz was definitely a factor in our music. Definitely. If you listen to Light My Fire, that part in the middle, the instrumental part, that was inspired by Coltrane’s My Favorite Things

The Ritual Begins At Sundown continues in this trajectory, loosely orbiting jazz, fusion and funk. The lineup features a number of Zappa alumni; Barrow on bass, Jock Ellis on trombone, Sal Marquez on trumpet and Tommy Mars on keys.

And they’re joined by Joel Wackerman and Joel Taylor on drums, AeB Byrne on flute, and saxophonists Vince Denim and Chuck Manning.

Krieger painted the album cover, an abstraction of a sunset. When asked, he describes his painting as “very free-form” but isn’t that true of his approach to the guitar, too?

“Well, I never thought of it that way, but yes, for me, painting and playing music is very similar,” he says. “There’s an element of chance to it. I try not to be constrained by your normal verse/chorus kind of thing.”

There’s a version of Yes, The River Knows, one of Krieger’s favorite Doors tracks, on the record. “If you listen to Ray’s part, it really is one of the best piano parts he ever did,” he says. It features Krieger’s slide guitar sitting in for Morrison’s vocals.

The first guitar I had when I first was in The Doors was a cheap Gibson Melody Maker, a $180 Gibson, and that sounded pretty good. I always say it is not the guitar that matters

Krieger would typically use his Gibson SG or Les Paul "Black Beauty," but not this time.

“I was over at Arthur’s house and he has this cheap, old Kay guitar and for some reason it sounds good on the slide, so I used that,” laughs Krieger. “I used that quite a bit for my slide in the last five years or so.”

Is that another lesson in there – that you don’t need a $2000 guitar? “The first guitar I had when I first was in The Doors was a cheap Gibson Melody Maker, a $180 Gibson, and that sounded pretty good, y’know? Not even a real SG, just a Melody Maker with those single-coil pickups, and it worked. I always say it is not the guitar that matters.”

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to publications including Guitar World, MusicRadar and Total Guitar. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.