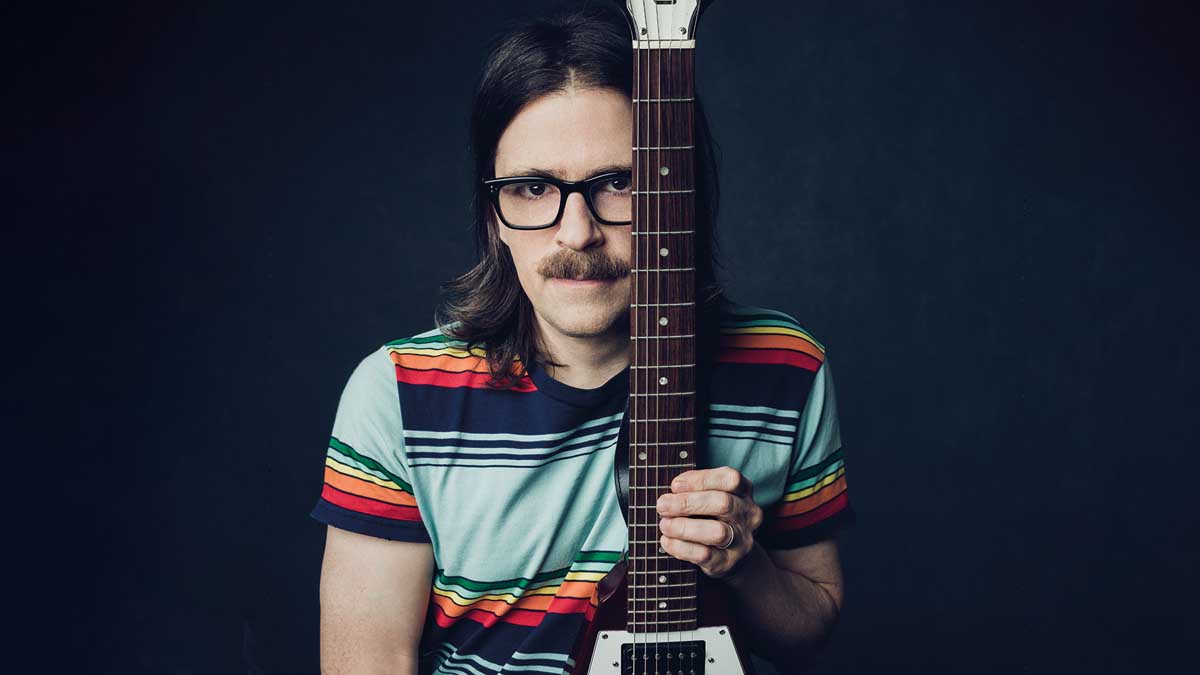

Rivers Cuomo: “We suppressed these impulses for many years... It was a real joy to open up that Pandora’s box of evil guitar tools and go crazy“

Given the fact that Weezer's latest album is called Van Weezer, (this from a band that has famously fashioned its flying “W” logo after Van Halen’s iconic “VH” wings), one might easily assume that the group’s frontman, lead guitarist and songwriter, Rivers Cuomo, is an avowed fan of the late six-string legend and company. This is a notion that he immediately puts to rest.

“Honestly, I’m not the Van Halen guy in the band,” he states emphatically. “I don’t really know anything about them. I got seriously into music and guitar with the micro generation right after Van Halen, so that would’ve been Ratt, Mötley Crüe, Iron Maiden, Judas Priest and Metallica. The other guys in Weezer were all super-into Van Halen.”

Interesting. However, the album is called Van Weezer, so one might surmise that in some way, even tangentially, it’s a tribute to Van Halen. Right? Cuomo chews on that for a second, and, without sounding the least bit coy, says, “Well, it could be Van Beethoven or Van Morrison. The first person I mentioned the record to said, ‘Oh, it’s a Beethoven reference.’ The second person said, ‘Oh, it’s a Van Morrison reference.’”

Finally, he owns up to it: “But you’re right. It’s a tip of the hat to probably the best-known band in the mainstream public consciousness to represent guitar shreddage.”

Van Weezer is the band’s second full-length release in 2021; earlier this year, the foursome (which also includes guitarist Brian Bell, bassist Scott Shriner and drummer Patrick Wilson) issued the transporting, orchestral-pop set OK Human (yes, its title is a winking nod to Radiohead’s OK Computer).

As it turns out, both albums were supposed to come out last year, but the COVID-19 pandemic threw a monkey wrench into Weezer’s plans.

The whole tour industry got shut down, the tour got bumped a year, and we realized it wouldn’t make much sense to put out a big rock album when we couldn’t even play

“This is confusing even to me,” Cuomo admits, “so let me figure this out. We started OK Human in 2018, and we were pretty much done. We started thinking about a release date and putting together a theater tour with an orchestra. Just then, our manager called and said, ‘Great news. You guys just got booked on the Hella Mega Tour with Green Day and Fall Out Boy, and you’re going to be rocking stadiums around the world.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Realizing that introspective, baroque pop wouldn’t exactly go over on a stadium tour, the band quickly changed gears and threw themselves into Van Weezer.

“We wanted to have a super-intense hard rock album so we could compete with the other bands we’d be playing with,” Cuomo says. “We worked fast, and we even got the first single [The End of the Game] out on iTunes. And then the pandemic hit. The whole tour industry got shut down, the tour got bumped a year, and we realized it wouldn’t make much sense to put out a big rock album when we couldn’t even play.”

With sure signs that the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic might be in our rear-view mirrors (at the time of this writing, the Hella Mega Tour is back on the books for June), Van Weezer might be the perfect album for our times – the anti-quarantine record.

Lyrically and musically, this takes us back to what we grew up playing. We suppressed these impulses for many years, so it was like coming home

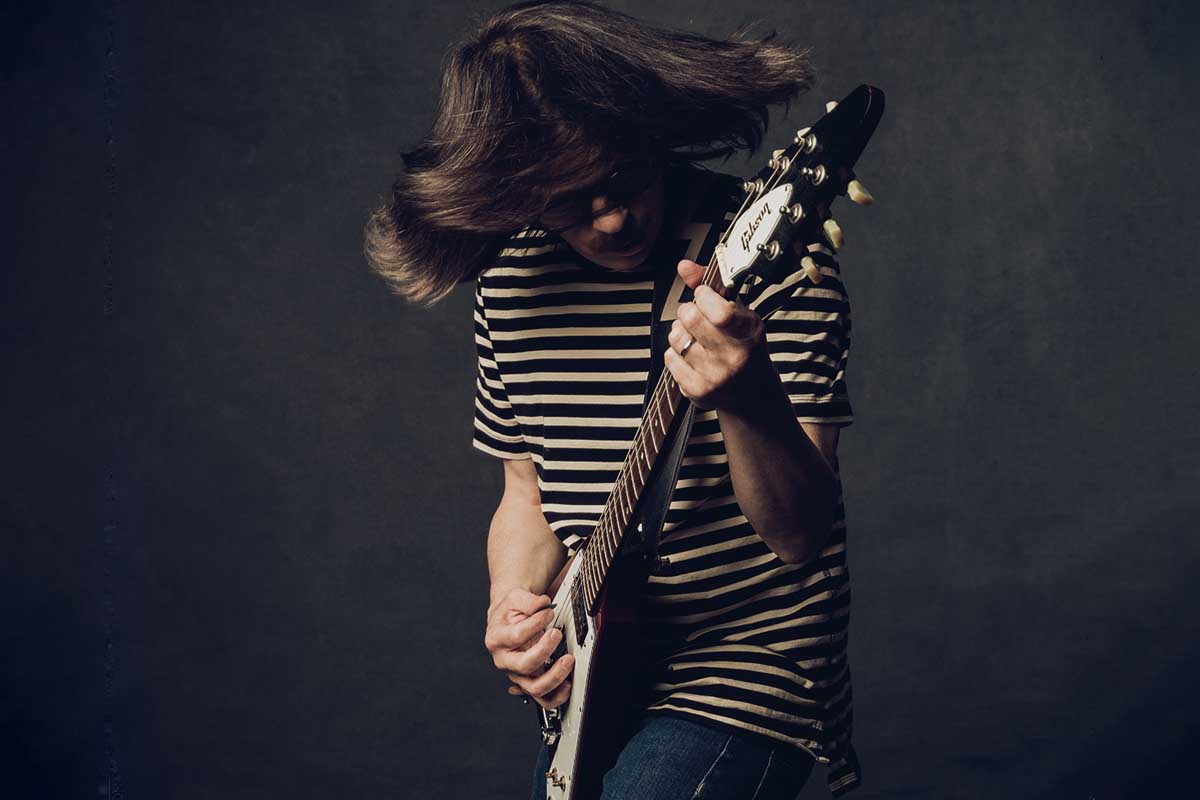

For sheer, unadulterated, roll-down-the-windows-and-crank-it-loud fun, its 10 tight, super-rocking, action-packed tunes – most of which don’t even crack the three-minute mark – deliver in spectacular fashion.

With its shredtastic intro, smart-alecky guitar squawks and anthemic pop hooks, The End of the Game gave listeners a good idea of things to come, and the band ups the ante on fast-ball doozies like Sheila Can Do It, Beginning of the End and Hero.

Lyrically and sonically, the album is an affectionate, nostalgic look at Cuomo’s formative, youthful rocking days during the '80s: amid squealing, twin-guitar leads, he recalls being “a little punk” listening to Aerosmith on the sing-along scorcher I Need Some of That, and while detailing teenage rock dreams of glory in Blue Dream, he lifts whole sections of Ozzy Osbourne’s Crazy Train (including Randy Rhoads’ iconic intro).

Even on the disc’s lone acoustic moment, the endearing set-closer Precious Metal Girl, he lets his mind race back to the Aqua Net-coiffed, spandex-clad female fans who used to chase bands like Faster Pussycat and L.A. Guns on the Sunset Strip.

“Lyrically and musically, this takes us back to what we grew up playing,” Cuomo says. “We suppressed these impulses for many years, so it was like coming home. It was a real joy to open up that Pandora’s box of evil guitar tools and go crazy.”

Evil guitar tools? Asked to elaborate, Cuomo explains, “Bar dives, two-handed tapping, artificial harmonics… It was like we had this intentional limitation of the colors on our palette. What’s striking to me was a very conscious decision to not employ the majority of guitar techniques that were at our disposal when we made our first record.

“Since the time I was 13, I had practiced really hard to master all these guitar techniques, but at a certain point the scene in L.A. decided that stuff wasn’t cool anymore. So it was like we pretended we don’t know how to do any of that – there’s not a single palm mute or any of those other techniques on our first album. And these are all things that I could do very well and had done in all my other bands up until that point.”

While acknowledging that Van Weezer has a decided thematic focus, Cuomo points out that making a concept album was the last thing on his mind.

“This is what we do now – we make very thematically tight albums,” he says. “Each album creates its own little world, but I think if we called it a concept album, people would get the wrong idea. They’d think there was a plot and a story and characters, and it’s not that type of record.”

At 50, Cuomo is now firmly ensconced in middle age, but he reveals that harkening back to his youth while writing the new record came easily.

“It’s interesting… My perception of time keeps getting distorted the older I get,” he says. “My twenties, that was a good decade there. After that, the thirties, and forties and beyond, it all becomes a blur. I still feel quite connected to my teens. Those are the formative years, and they’re still right there inside of me.”

Let’s go back to your introduction to hard rock and heavy metal. What was the first band that hit you?

”I think the moment I was converted to being a metal head, when it really became more than just music, was when I heard Quiet Riot’s Metal Health on the radio. That was when I started to feel this sense of identity and belonging to a community.”

Were you already playing the guitar?

”I had a drum set. My brother got a guitar, and I noodled a bit. But right after I heard Quiet Riot, for my eighth-grade class night, there was a group of boys who put together a band, and they covered Metal Health. They played the opening riff, and the singer slid across the stage on his knees while screaming.

”I couldn’t believe kids just like me, my age, got these instruments and were making this sound. It was so exciting. Within a few weeks, I got a white Yamaha Strat copy. That was for my 14th birthday, and I just started practicing and practicing.”

Over the course of high school, I got pretty good at the heavy metal thing, and I went to Berklee School of Music for a summer program

Were you a natural on the guitar? Was it arduous?

”It was frustrating at first, because there were so few resources back then. There was obviously no internet, and even songbooks – I got a Kiss songbook, but it was for piano and vocal. They had chord diagrams so you could strum an acoustic guitar, but I was trying to play the Cold Gin riff, and it didn’t sound right.

”On the other hand, nobody had anything else to do, so it was easy to get some friends and form a band in a shack over at my friend’s house. We’d play Cold Gin over and over, and we gradually figured it out. We learned by ear. Over the course of high school, I got pretty good at the heavy metal thing, and I went to Berklee School of Music for a summer program.”

You must’ve had your chops together to be accepted.

”Well, it wasn’t Berklee proper. It was a five-week summer program for high school kids. I don’t remember how selective it was, but I was pretty good.”

Who were your main guitar heroes at this point?

”The first one was Ace Frehley. I learned all the Kiss songs, and my first band was a Kiss cover band called Fury. With my 14-year-old logic, I thought I could make it as a musician playing somebody else’s songs. I just thought we were going to be Kiss, but called Fury, and that we’d make it somehow. And then I had another band called Warlock, and we did Priest and Maiden, Mötley Crüe – everything that was popular in the early and mid-'80s.”

With my 14-year-old logic, I thought I could make it as a musician playing somebody else’s songs. I just thought we were going to be Kiss, but called Fury

”I also have to give due credit to the later metal bands. I got into a Metallica cover band, a Fates Warning cover band. I got into Yngwie Malmsteen and a band called Cacophony that featured Jason Becker and Marty Friedman. I just loved that so much, so that’s where my head was at when I moved from Connecticut to L.A., right after high school. My band hit the Sunset Strip, and we were like, 'All right, we’re going to take this place over, because we shred like nobody else!'”

I assume you mastered tapping. Thanks to Van Halen, it was de rigueur.

“Yeah. I didn’t get it from Eddie, but from the guitarists he influenced. Definitely, whatever the cool new guitar trick was, that’s what I was learning. At the time, it felt like it was really hard. I remember my fingers hurt from all the practice, but it all seemed to happen within a couple of years. I was thinking, 'I’m pretty hot on guitar,' which is kind of funny.“

There was a decided macho and sexist element to hard rock and metal in the '80s. Guys were wearing leather, and the videos featured women in strip clubs. All of which doesn’t seem like you, certainly not at that age.

“I don’t know… I think the whole gender thing in metal is pretty complicated. I don’t think it’s as simple as metal being macho or uber-masculine, because I think quite a lot of it was hyper-feminine, with the long hair, makeup and glam. I remember we all thought being really skinny and not built was cool. If you were muscular, it was like, 'Ew, that’s not cool.' It’s complicated, and I don’t have the gender studies background to understand it.“

Whatever the cool new guitar trick was, that’s what I was learning. I remember my fingers hurt from all the practice

If I can attempt to draw a parallel between you and Eddie Van Halen, it seems that while your high school friends were out partying, the two of you spent a lot of time practicing alone. Fair comparison?

“Yes, except I had great friends, and we were all in the same boat together. We were all learning together, and there were so many musicians in my school trading ideas. I definitely didn’t feel like a loner in my work as a musician.“

Eddie was a pioneer in guitar construction. He made modding guitars very popular. Did you do any of that?

“No, I didn’t, and I have never had any kind of technical skill or interest around anything mechanical. My brain doesn’t go there. I’ve thought about that recently, because in the last five years, I’ve discovered this incredible enthusiasm and knack for computer programming. It’s not a physical object, but it’s a lot of modding other people’s scripts, and I just love it. But put a physical object in front of me, and I’m pretty much useless. I can’t even figure out the TV remote control.“

I got a job at Tower Records, and while working there I was exposed to all kinds of music. The people there schooled me. They’d put on Pet Sounds, the Pixies, Sonic Youth…

At a certain point, you switched gears from metal. You got into the Beatles and the Beach Boys. I understand that the Pixies also made a big impression on you.

“When my band got to L.A., the Sunset Strip was in the midst of the Guns N’ Roses phase. Everybody was trying to figure out who was the next Guns N’ Roses, and nobody knew what to make of us. We couldn’t get off the ground, and most of the guys in my band went back to Connecticut. I got a job at Tower Records, and while working there I was exposed to all kinds of music.

“The people there schooled me. They’d put on Pet Sounds, the Pixies, Sonic Youth… At first, it just sounded like a bunch of painful noise. Coming from my metal background, I didn’t know what to make of it, but over the course of 40 hours a week, week after week, I was like, 'Oh, this is kind of great. I kind of dig this.'

“My focus shifted from 'How clearly can I play these harmonic minor scales and sweep arpeggios?' to 'How catchy can I make a chorus?' Or 'How emotionally honest can this verse be?' It was still the same focus on intense achievement, but now my trade was as a writer [rather] than a shredder.“

It was a real growth period.

“It was. But also, let me talk about singing. Even in my early days, I sang. I sang in the Kiss cover band. I sang in the school chorus, in a barbershop quartet, in madrigals. I loved singing, but I didn’t think of myself as a deep singer. I couldn’t hit the high notes like Geoff Tate from Queensrÿche or Rob Halford from Judas Priest. I just didn’t think I could sing like that.

“In my serious metal bands, I was never the singer; I just thought of myself as a guitar player. But as I was exposed to all these alternative bands while working at Tower Records, I started to realize it wasn’t so much about how high or how powerful you could sing. It was more like, 'Do you have something to say?'

“When Weezer started, that’s when I really became a lead singer, because I realized I didn’t have to try to be like a lead singer. I could just be my normal self and sing like I did in choir. After that, it was quite easy. And the best training for a singer is to play shows, so we did that all the time. We played show after show in clubs.“

So much of my technique is from learning Ratt songs or even the Scorpions

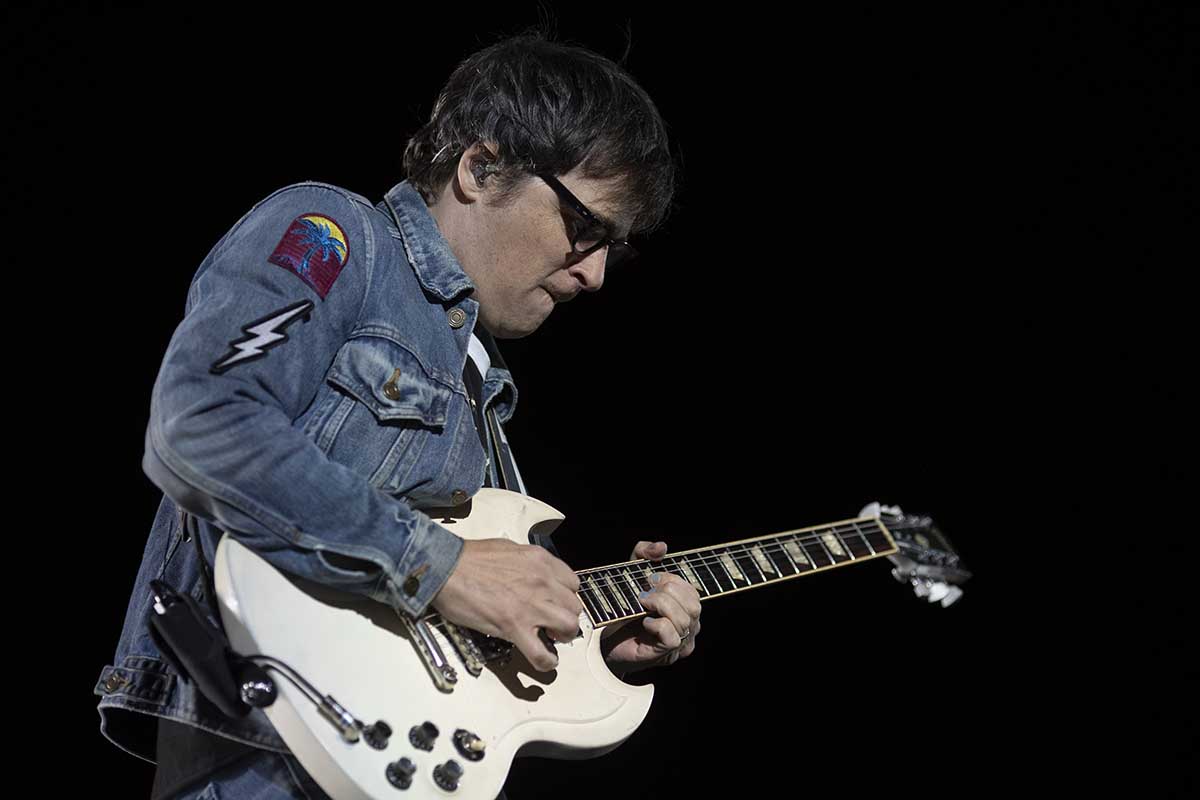

Let’s get into Van Weezer. The End of the Game starts off with some tapping that sounds very Eddie-esque, though you’ll probably disagree.

“Actually, I was trying to emulate AC/DC’s Thunderstruck. It’s not even tapping, I don’t think. I was just like, 'How can I do something like that?' So I pulled out the first technique that sounded somewhat like that. I think that’s how it came out. I really like that harmonized tapping, and I also like the bar dive on the double artificial harmonic.

The rhythm patterns are really forceful.

“That’s got to be from Ratt, I think.“

Warren DeMartini – he’s quite underrated.

“Yeah. I mean, I have no idea how any of those records were made. It was before I knew how to research that stuff. But definitely, so much of my technique is from learning Ratt songs or even the Scorpions.“

I Need Some of That is such a sweet look at youthful rocking. You namecheck Aerosmith and sing about plugging into a Marshall stack…

“That one’s tough for me, because, man, we wrote so many versions of it and had so many different lyrics. I’m pretty sure I was thinking about those days at the shack at my best friend Justin’s house. That’s where we used to practice all the time.“

What’s going on in Blue Dream? The riff, and even the drums and the verse chords – that’s Crazy Train by Ozzy Osbourne.

“[Laughs] Pretty similar.“

I’ll say. Did you have to split the songwriting?

“Yeah. They get half the song or something like that. It’s kind of like a sample, really, but we played it.

How did it come about? Were you playing Crazy Train and you thought, “I’m going to write a song around that”?

“The song existed with another riff. The song was good, but the riff was… It was OK, but it wasn’t the greatest guitar riff of all time, which I felt like it should be. Coincidentally, at the same time, our manager said, 'Hey, you guys should sample the Crazy Train riff in a song.' I know he was thinking: 'What’s going to get people talking? What is going to confuse the internet?' He had no idea what I was making, but it just seemed to me like the perfect suggestion. So we tried it. The tempo fit, and it all just seemed to come together.“

Did you ever hear a reaction from Ozzy?

“They approved it, so I’m assuming he heard it. I don’t know what their approval process is, but I didn’t get a specific reaction.

“That’s not the first time we contacted Ozzy. Actually, once, I think it was in 2000, he asked if I had any songs for him, and I just happened to have written Hash Pipe. I sent it to him, but he didn’t end up using it. In another reality, it might be interesting to hear him singing that song.“

We haven’t really talked about thrash metal. One More Hit has a section that’s pretty doomsday and thrash-like.

“That dissonant Slayer mosh riff was a satisfying moment. That’s an itch I haven’t been able to scratch in all previous years of Weezer’s history. I went through a huge Slayer phase. I remember right around the time I was learning to drive my parents’ Toyota Tercel, I’d drive up and down the driveway blasting Reign in Blood.

“We had a short driveway, so I’d turn around and come back – over and over, just gunning the car. That record was exactly what I needed in my junior and senior years of high school. It had a lot of aggression.“

Nothing feminine about Reign in Blood.

“[Laughs] No. Not a lot of hairspray and makeup on that album.“

Speaking of hairspray, on Precious Metal Girl you do a beautiful acoustic love letter to the women on the Sunset Strip in the '80s.

“Yeah. They were really special. I don’t know if those girls exist anymore, but I have good memories of the smell of the hairspray and the makeup. They’re just great inspirations.“

You namecheck some of the mid-level bands of that era – Faster Pussycat, L.A. Guns. Were you a fan?

“I was more into the girls that were into them.“

[Laughs] I see. I want to ask you about Suzy Shinn. She had been your engineer on a few records, but on Van Weezer she makes her production debut.

“You know, I’m very resistant to new people around me, especially when I’m singing or writing in a very deep space. I need familiar surroundings. When I first met Suzy, we were making the White Album. I went to a session and was going to finish writing California Kids. I was there with [producer] Jake Sinclair, whom I was really excited to work with. Suzy was in the room, sitting behind a desk, and I was immediately thrown off my game.

“Not only was some random person there, but she was this young woman. I was like, 'How am I supposed to operate here? This is not cool, Jake.' But she had the perfect temperament. She was very laid back and unobtrusive, but at the same time she worked really hard.

“As I got more comfortable with her, she started pushing me more than any producer ever did. So I got dependent on that, and every time I had to sing, I would ask her to basically produce my vocals. After a while, it just seemed like, 'Why not have her do the whole record?'“

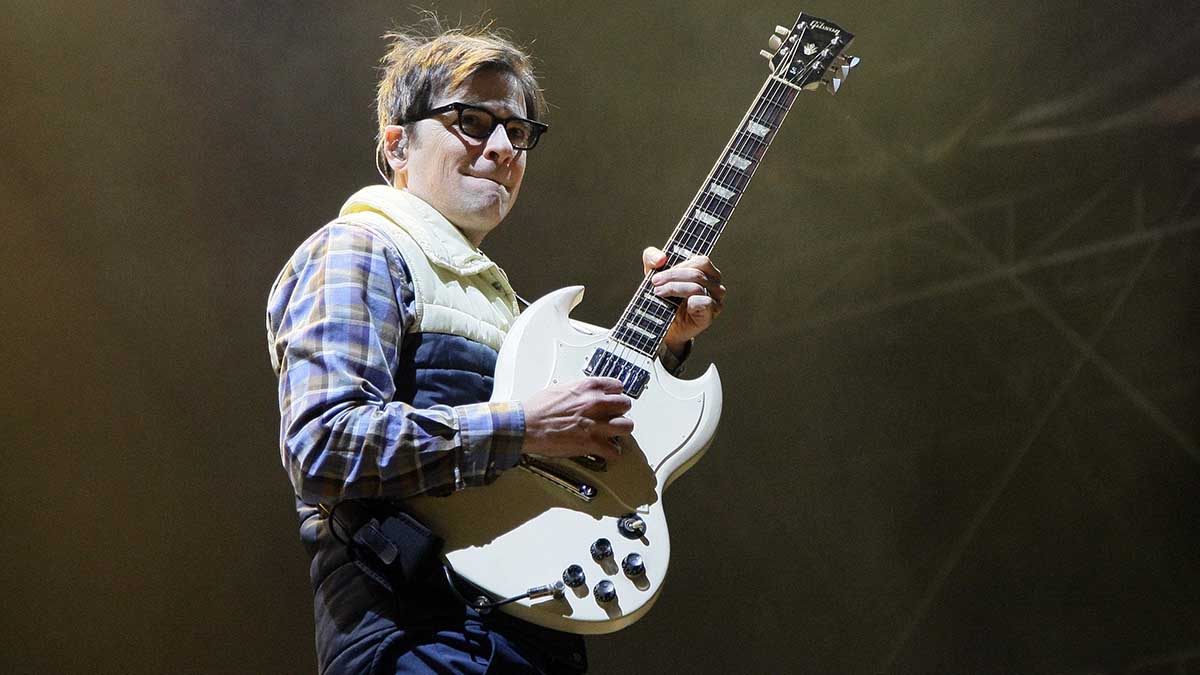

What were your Van Weezer guitars?

“We started with the idea to pull out some of the guitars from that era and get some of those sounds, but then we realized the album is called Van Weezer, so you’ve got to have as much Weezer as you do Van. So we made sure the meat and bones of the album were straight-up, classic Weezer sounding. I used the Les Paul Junior that I got from Ric Ocasek and played on our first album. I used the same Boogie amp, too. I think it all sounds like classic Weezer.“

How about your Warmoth Strat copies?

“I never use those on records. They sound good on stage, but they can’t compare to the Les Paul in the studio.“

Anything else?

“There was some Explorer and other guitars. But then we’d send out for guitars. It was like, 'We need an absurd guitar with a whammy bar on it,' so we’d sound out to Truetone in Santa Monica or to Lon Cohen Studio Rentals – 'Send us a crazy guitar.' The studio quickly turned into Guitar Center, with all this mad shredding going on. It was super-fun.“

- Van Weezer is out now via Crush Music/Atlantic.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.