“I made my own bass and used bicycle brake cables as strings…” How Richard Bona went from homemade guitars to being hailed as “the African Jaco”

"I don't want to play for bass players – I want to play for truckdrivers! I want people to dance!" The rise of a reluctant virtuoso

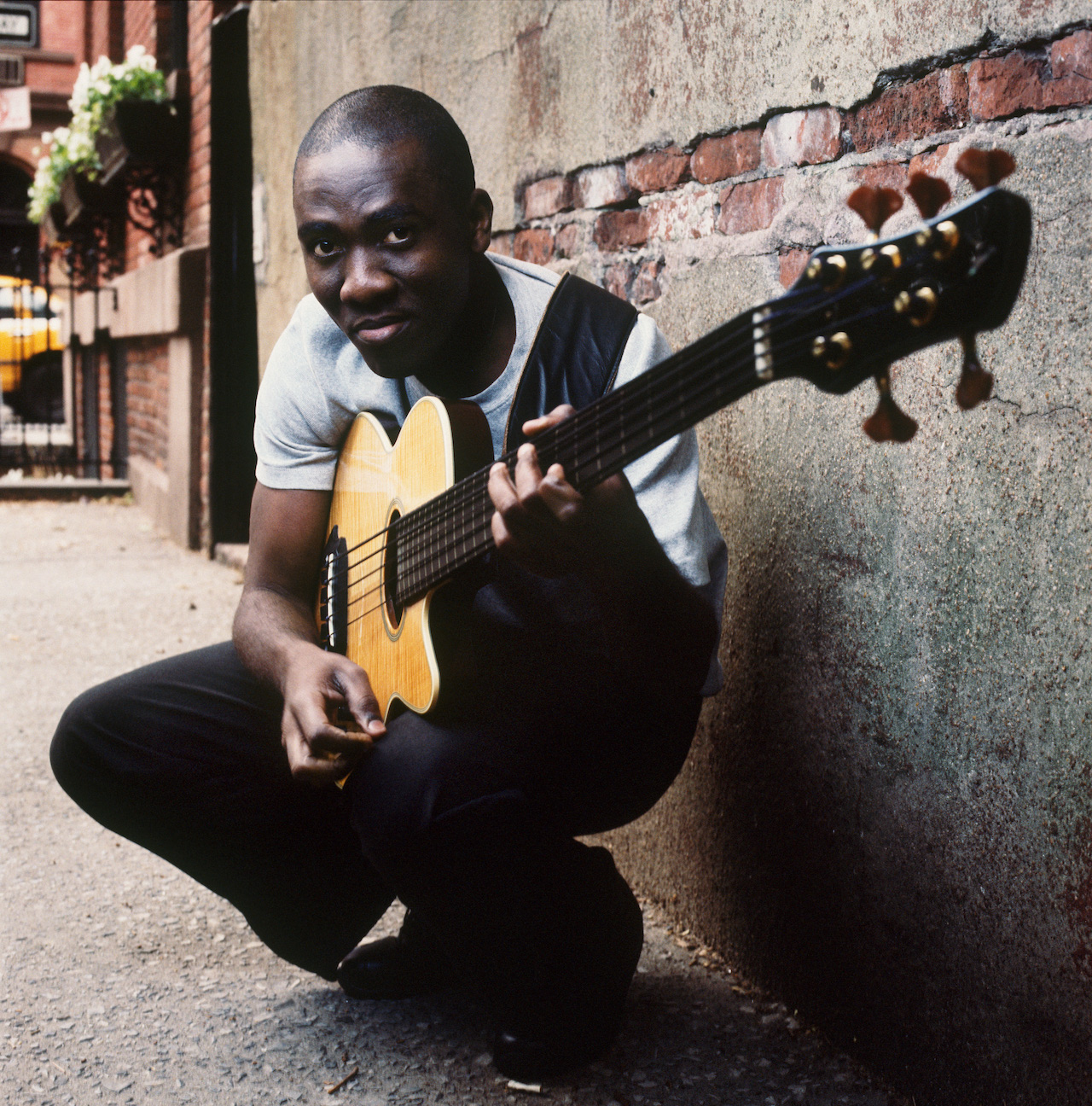

Richard Bona is tired. Tired of posing for photographs, tired of being shuttled around London from one interview to the next, tired of talking about his past, and tired from doing two shows a night at London’s Ronnie Scott's, tired of finishing at three in the morning.

"Man,” he says, "I'm so darned tired of bass playing."

We think he's joking.

It is summer 2000 and Richard Bona is working hard to promote his debut solo album Scenes From My Life. Already he has played with the great Manu Dibango and Salif Keita, played with the Brecker Brothers in New York and done sessions for George Benson, Chaka Khan, Steve Gadd and Bobby McFerrin, and he will go on to greater things. But back in 2000, he was stepping out of the shadow of these famous collaborators and quietly blowing the minds of everyone who heard him. (In the bar at Ronnie Scott's we bumped into Terry Gregory, the sometime bass player for Martin Taylor. What did he think? Terry rolled his eyes: "He's just full of music, isn't he?" he said.)

Born in a small village in Cameroon, West Africa in 1967, Richard Bona's story is a remarkable testiment to his talent – which he took from that village to the jazz clubs of Paris and then New York, playing with some of the world's best jazz musicians and being compared to the most revered bassist of them all.

Weather Report's Joe Zawinul used to introduce him onstage as "the best bass player I've ever worked with". ("It was nice," says Richard now, "but I had to say to him, ‘How about you introduce me as Richard Bona? This is too American for me'") and Bass Player called him "the African Jaco", which perhaps ignored another important part of his talent: Richard Bona isn't just some Jaco copyist, big on bass solos and 100 mph chops, but a great singer and songwriter. Scenes From My Life is African jazz: beautiful melodic vocals, sweet melodies and fantastic but understated bass parts.

Live, Bona is an even more exciting proposition for a bass player, as the band lock into the most amazing grooves. The word we often use to describe playing like Richard Bona's – 'fluid' – just isn't adequate in his case. Richard Bona's playing is fluid like the Niagara Falls is fluid: we're talking rivers of bass here, fountains of bass, swelling dams of the stuff. 'Fluid' just doesn't cover it.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Part of a musical family, Richard Bona grew up playing percussion and the balafon ("an African xylophone, like marimba"), and as an infant played at weddings and celebrations in his village. His life changed when a Western tourist with a guitar came to his village. "I saw a tourist – an English guy, I think," says Richard, "with an acoustic guitar and he stopped and played a song for me. I'd never seen a guitar before. I looked at how it was built and I started building one of my own the next day.

"I went to the guy who repaired the bikes in the village and stole the brake cables for the bikes and used them as strings. I was a comedian. I cut my fingers about 3000 times! They were so hard! But the hardest thing was trying to tune the guitar, so I used my own tuning, based on the balafon tuning. And I just made up my own chords. Then my father got a job in the city as a truck driver so he took us to the City – I was 11 years old. I had a homemade 12-string guitar – and the kids in the city were playing real acoustic guitars and they just laughed at me: 'Ooh – that's not a guitar! Fffff. Who made that nasty-looking thing?'"

Getting himself a proper guitar, Richard (aged 11, remember) was soon playing in all-night bars. "In the city there's a lot of bars and people dancing every night, so I would start at nine and play until six in the morning, non-stop. And I did that for 11 years."

One night, when Richard was 15, a French guy came to check him out. He wanted to set up a jazz club in the city and had heard of this amazing young guitarist. "Because I had played balafon for many years, my ears were so sharp rhythmically and play the same thing. But he saw me and he said, 'I don't want this dance music, I want jazz.' I said, 'What the fuck is jazz? What are you talking about, man? First of all, how much are you gonna pay? 'Cos you want me to play music I don't even know, man. I never heard of this music'.

“He says, 'How much money are they paying you here?' I tell him. He says, 'Okay, I'll pay you 20 times that a night.' I said: 'Hey, alright – I want to play jazz now!"

But first of all, Richard had to find out what jazz actually was. "I went round to this guy's place. He had like 400 albums, all jazz music. I hadn't heard of any of them. So I picked an album and played Portrait Of Tracy by Jaco Pastorius. Now bass players back home – they're good, very good, but always in the background – so I heard this and thought 'Wow’. I thought the turntable was running fast – so I checked it and it was at 33rpm. I was like, 'That guy's fast, man! How does he play the bass like that?' And that day I switched from the guitar to bass. In three months I knew every solo on that album."

Bona's all-night shows at the bar became bass-only shows. He then moved to Paris to get more involved with jazz and then to New York, where he got the hallowed bass job with Joe Zawinul and worked as Harry Belafonte's musical director. And despite the 'new Jaco' tag (a description he's ambivalent about – reluctant to be seen as a mere disciple, but more than willing to acknowledge his debt – every Thursday when he's in New York he does a tribute to Jaco at a city bar), he didn't want to follow in the footsteps of so many Jaco-inspired bass players and do a 'bass album'. Thank God.

"I didn't wanna do that," he says. “'I wanted to really get away from that." He points at Paul McCartney on the cover of an old copy of Bassist magazine: "He was great. The Beatles – one of the greatest bands ever. They were songwriters, man. I mean, you take them aside; they weren't great on their instruments, but that is where the magic of music comes in: it's not all about playing. My vision of music is the big picture, and the bass is here [holds finger and thumb apart] and the guitar is here [holds them apart again], but they all make music.

"There was this bass player I know. I went to Berklee and I said to him, 'I saw you playing in New York and when I saw your album I was so happy that I bought it and went home and have to use my heart was broken! It's about the music. You can't just focus on one thing. Bass is a part of the music. I want to play some music – not just for bass players – I want to play for everybody. And that's how people on the street are going to discover more bass.

“You play them one of those bass albums? Those guys on the street'll be like, 'Oh, I don't get it, man'. Bass is a wonderful instrument, but we have to use it to play some music, not this 'circus' thing. That's putting bass in a ghetto. I don't wanna play ghetto bass. I wanna play bass for carpenters in London, or truckdrivers in Manchester! I came from a culture where we make people dance. That was my culture, not showing off.

"I used to play with my grandfather," he says to illustrate the point. "We'd play a song for two hours. You don't move, man. In the schools, they don't teach that. They teach them what you can do over the rhythm. It's what I said last time I went to Berklee and Los Angeles: 'You play bass, okay, but one thing you have to learn is what the role of the bass in the music is. Look at the role of the violin, the guitar, the harp, the bass. What makes the bass sound good in the music?'

"They don't teach kids that concept. They teach them scales and all these things, and as soon as you start playing in a groove, all of a sudden they want to experience something else over the groove.

They haven't even caught the groove yet. It takes a lot to understand the groove of a song, to be into the line. Some people it takes them one year, two years. They play the line, but they're not in the center, where you and the line become one."

So this is Richard Bona: the bass player who can play like Jaco, but just wants to get you dancing. The virtuoso who isn't all that impressed by virtuosity. The guy who used to build his own guitars and doesn't much want to talk about gear. He plays a Federo five-string, a four-string Pensa Suhr and has a fretless Fender Jazz that he doesn't like to use: "When people hear me play on the Fender, right away they say, 'Oh – Jaco' So the Fender will stay home for a while."

Richard Bona: the singer who's known for his musicianship ("I always tell my students: 'Sing your lines, all the time. Anything you play on the bass, sing it. That's how you catch that groove easy. And then singing will become easier too'"), the bass player that realizes that you have to be more than good on the bass to move people. You have to be an artist.

"Sometimes I write songs on the bass," says Richard, "sometimes I do it just walking in the street. You hear a coin falling: 'bing!'” He scat-improvises a jazz melody based on the sound of the coin falling. “I'm a storyteller. I want people to relate to the story. And as an artist I think we have a responsibility to make this world beautiful, to always remind people that life is wonderful."

Follow Richard Bona on Instagram

Scott is the Content Director of Music at Future plc, responsible for the editorial strategy of online and print brands like Guitar World, Guitar Player, Total Guitar, Louder, Classic Rock, Metal Hammer, Prog, Guitarist and more. He was Editor in Chief of Classic Rock for 10 years and, before that, the Editor of Total Guitar and Bassist magazines. Scott regularly appears on Classic Rock’s podcast, The 20 Million Club, and was the writer/researcher on 2017’s Mick Ronson documentary Beside Bowie.

“I asked him to get me four bass strings because I only had a $29 guitar from Sears”: Bootsy Collins is one of the all-time bass greats, but he started out on guitar. Here’s the sole reason why he switched

“I got that bass for $50 off this coke dealer. I don’t know what Jaco did to it, but he totally messed up the insides!” How Cro-Mags’ Harley Flanagan went from buying a Jaco Pastorius bass on the street to fronting one of hardcore’s most influential bands