Poison Ivy: “It was easier for me to consider playing guitar because I was such a misfit. For me, anything was fair game”

In this previously unpublished interview, the guitarist, songwriter and producer of the Cramps looks back over decades of hoodlum music

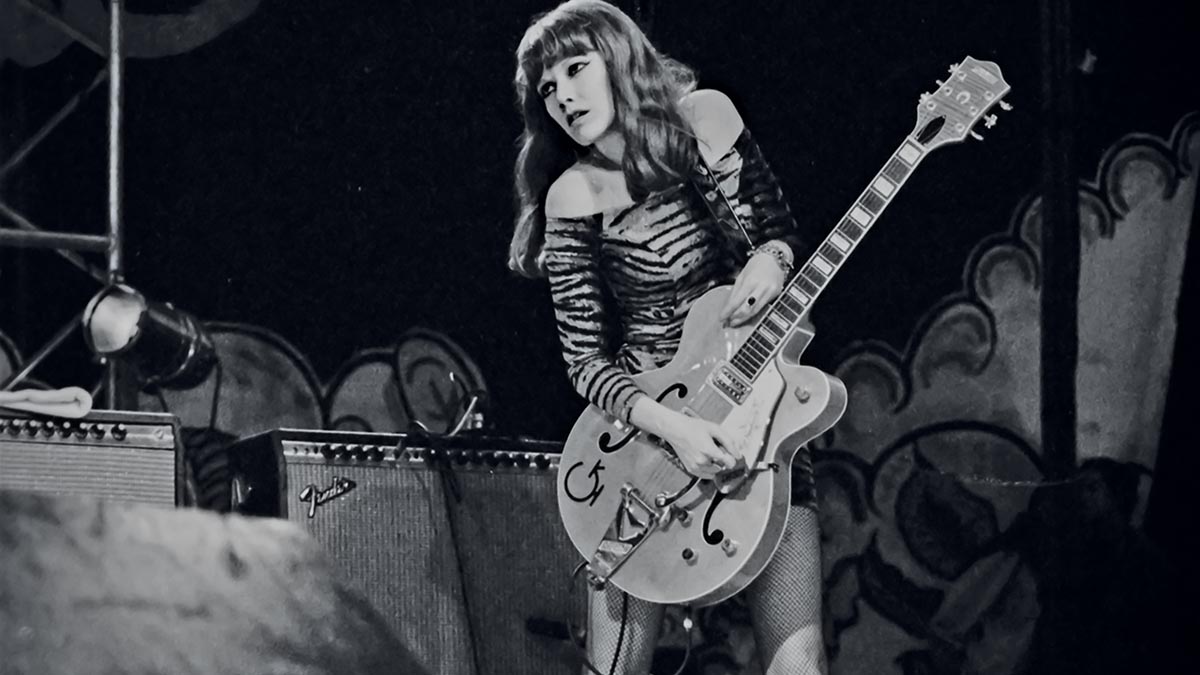

They came outta Sacramento, California, and Akron, Ohio, their heads full of B-movie violence, cut-throat rock ’n’ roll and fetish-mag filth. They were the Cramps. The men looked like creeps and killers. The woman, Poison Ivy, looked like a high priestess or a '50s movie queen.

In a flip of the usual showbiz dynamic, the singer wore high heels and ended almost every gig naked while his partner – the woman – ran the show. She produced, managed, wrote the music, played the guitar and frequently reached over to tune the guitars of her bandmates.

They might have seemed deviant, but the Cramps nevertheless played all-American music – the kind of music that had rocked the country before the British Invasion – a Frankenstein’s monster stitched together out of the blues, doo-wop, rockabilly, country, R&B, exotica, garage rock, psychedelia, instrosurf and more.

The Cramps were rock ’n’ roll as remodeled by Roger Corman, Russ Meyer and John Waters. Their sound – and that of the music they popularized and reintroduced – echoes in the movies of Quentin Tarantino and haunts the soundtracks of Angelo Badalamenti.

They hung out with the Ramones and toured with the Police. The White Stripes owe them. Queens of the Stone Age covered them. Nick Cave nicked two of their band members. My Bloody Valentine’s Kevin Shields told Guitar World that he formed a band because of Cave’s the Birthday Party and the Cramps. Fugazi/Minor Threat’s Ian MacKaye once claimed that a Cramps gig kickstarted the D.C. hardcore scene.

They were an influence on grunge, pioneered psychobilly and they spilled over into goth. They made other rock ’n’ roll revivalists – with their songs about drive-ins and hot rods – look lame. The Cramps, you see, were born bad and stayed sick. Their songs were about drugs and sex, monsters and perverts.

They were dangerous, yeah. But, man, they were funny.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

And at their heart was a couple. For all the drugs, deviance and delirium, the story of the Cramps is a love story – the story of Lux Interior (vocals, words) and Poison Ivy Rorschach (guitars, music). Lux took the vocal tics of rock ’n’ roll and exaggerated and amplified them: stuttering, hiccupping, yelping and gulping for air. Equally, Ivy made her guitar squawk like a chicken or buzz like a fly.

She took the mannerisms of Duane Eddy, Link Wray and Dick Dale and turned them up a notch. She took reverb, tremolo, sustain and fuzz – those bad, bad boys – and whipped ’em into shape, handcuffing them to licks sharper than stilettos. Other band members came and went. It didn’t matter: Lux and Ivy were the Cramps.

When Lux died suddenly in 2009 (from aortic dissection – his heart literally burst), the story ended. Ivy went underground – and still doesn’t get the credit she’s due.

I interviewed her in 2003 for the guitar magazine I worked on at the time. I got a new job weeks later and the interview was never used. Until now.

“Nobody ever talks to me about music or guitar,” she once said. “I’m the queen of rock ’n’ roll, and for this not to be recognized is pure sexism.”

Bow down before your queen.

In the beginning, there was The Chord. “Link Wray is all about The Chord,” Ivy says. “A monumental chord and the drama of it. It’s very haunting, stark. He had that thing I call ‘the grind’ – that really fast, grinding, dead strumming. With Link Wray it’s about the chords and the drama. It sounds dangerous to me, it sounds spooky.”

And alongside The Chord comes The Note.

“With Duane Eddy, it’s all about The Note,” she says. “A single note, just the ultimate twang. Duane Eddy also sounds spooky. They both have drama. He had those backing vocals that sound like they’re ghosts, y’know, from hell.

“They just sound like they’re dead to me. I always pictured it like they’d been on a chicken run or some-thing and got killed and now there they are, howling away on Duane Eddy records. His early stuff like Ramrod and Stalkin’ was just rough, dangerous hoodlum music. That’s who bought that stuff.”

And once you’ve got The Note and The Chord, the final ingredient in this hoodlum gumbo is... aggression?

“Another guitarist I love is Ike Turner,” she says. “He produced a lot, and he considered himself more of a piano player, but his guitar playing was totally unique. He musta got a Stratocaster the day it came out and he went nuts with the vibrato bar. It’s insane. If you see pictures, he has these really long fingers and huge hands wrapped around a skinny Stratocaster neck.”

A fascination with Jack Nitzsche’s 1963 hit The Lonely Surfer led Ivy – or Kristy Marlana Wallace, as she was known then – to pester her older brother Jerry into showing her the basics of guitar playing. “Then when I was a teenager, I got even more interested,” she says. “I had boyfriends that played guitar, and I was more interested in the guitar than I was in them. I would trick them into teaching me things.”

Her life changed on Valentine’s Day 1970 – the day she went to the Sacramento Memorial Auditorium to see Quicksilver Messenger Service, supported by Eric Burdon’s War and Bo Diddley. It was a lightbulb moment.

Diddley had long included a female guitar player in his band. From 1957 to 1962 he had Lady Bo, aka Peggy Jones – aka “the Queen Mother of Guitar” – who played on classic singles like Hey! Bo Diddley, Mona and Road Runner.

When Jones left to go solo, Bo replaced her with another female player, the Duchess, aka Norma-Jean Wofford. Norma-Jean lasted until 1966. Bo apparently replaced her with a series of women he called the Duchess, but it’s possible that the woman Ivy saw that night in Sacramento was actually Lady Bo, who had returned to the touring band that year.

Whoever she saw, the powerful woman onstage playing rock ’n’ roll and oozing sex and style made an impact. “That did it,” Ivy later told an interviewer. “They did all this synchronized box-step dancing, and she was in gold lamé. That just burned through my brain permanently.”

By the time she met Lux, then called Erick Lee Purkhiser, she was an outsider and confirmed rock ’n’ roll obsessive. (Was it Ivy’s outsider status that led her to guitar playing? “Maybe it was,” she says. “I didn’t even think of that ’til you said it, but maybe that made it easier for me to consider playing guitar because I was such a misfit anyway. Maybe it’s harder for someone who fits in to do that. For me, anything was fair game.”)

In Erick she had met her match. He was as batshit crazy about rock ’n’ roll as she was, and they set about forming the Cramps.

In an age when band names were getting more abstract – Iron Butterfly, Aerosmith, Grand Funk Railroad – they wanted an old-school name like the Kinks, and they came up with one that referenced menstrual cramps. Kristy had already become Poison Ivy in 1973.

The name came from the Leiber and Stoller-penned 1959 Coasters hit. “She’s pretty as a daisy,” go the Poison Ivy lyrics, “but look out, man, she’s crazy / She’ll really do you in / If you let her get under your skin.” Seemingly about a dangerous female, and therefore befitting Poison Ivy’s tough-gal schtick, Jerry Lieber later admitted the song was “a metaphor for a sexually transmitted disease – the clap.”

Her band was named after period pains – and she was named after VD. Sex and danger were there from the beginning. “Lux and Ivy were rock ’n’ roll names,” she says. “We were 24-hours-a-day rock ’n’ rollers.”

In a method that prefigured sampling, throughout their career the Cramps borrowed bits and pieces from obscure tracks to make their own material. On their first single, Human Fly, Ivy makes her guitar sound like the buzzing of a fly, in the same manner as the Tune Rockers’ 1958 novelty hit The Green Mosquito.

The Riptides’ Machine Gun and Bo Diddley’s Dancing Girl went through the blender and were squirted out as Call of the Wighat. Ivy borrowed the intro chords of the Instrumentals’ Chop Suey Rock (and Lux rewired the lyrics from Dall Raney and the Umbrellas’ 1964 single Can Your Hossie Do the Dog) for their far more salacious Can Your Pussy Do the Dog?

They did blistering covers of lost rock ’n’ roll, garage and country classics – the Sparkles’ Hipsville 29 B.C., Macy Skipper’s Bop Pills, Charlie Feathers’ Can’t Hardly Stand It, Jack Scott’s The Way I Walk, the Trashmen’s Surfin’ Bird and Roy Orbison’s A Cat Called Domino.

Sometimes the songs were so wild, and so perfectly welded to the Cramps’ aesthetic, that you couldn’t believe they were covers; take the Novas’ The Crusher – a twisted “dance” record that instructs you to eye-gouge and “squeeze your partner’s head until she’s blue in the face.”

Then there was Goo Goo Muck, the song that became a viral hit after Netflix's Addam's Family reboot Wednesday featured it in a dance scene, a 1962 novelty song transformed by Ivy into a sinister Duane Eddy-eque nightmare for the Cramps’ second album, Psychedelic Jungle (the lyric “I’m the night head-hunter looking for a head” changed to “looking for some head”). It turns out that American music in the '50s and '60s was some sick shit.

Ironically, this musical archeology was inspired by the British Invasion. “The first Led Zeppelin album came out when I was a kid,” she says. “I played it to death. It’s interesting to me now that bands that are influenced by Led Zeppelin don’t go back to the things that Led Zeppelin and the Yardbirds would’ve been influenced by. They only go back to Zeppelin and Aerosmith. With us, we’d take it right back.

“My favorite Rolling Stones period is the early '60s. That’s what got us into all the things the Rolling Stones were into – Howlin’ Wolf and Sonny Boy Williamson and all that. Everyone we knew did that. Everybody who was into the Kinks and the Rolling Stones was also buying all those blues records.”

The Cramps guitar sound came naturally. “I had one thing as a kind of criteria,” she says. “We loved Chuck Berry, but we had a rule that we wouldn’t do Chuck Berry licks. All rock ’n’ roll from the '60s, going into the '70s, was based on Chuck Berry, at the exclusion of any other influence. So even though we loved Chuck, we decided to do all we could to not have that influence. There was too much, y’know?”

Even the Sex Pistols had Chuck Berry licks. “Yeah. And it’s astounding; you never would hear Link Wray influences or Duane Eddy. We couldn’t figure it out because it was pure rock ’n’ roll. It’s as monumental as Chuck Berry, and for it to be ignored seemed strange. So to this day, it’s a rule: we will not throw in a Chuck Berry riff.”

Do you have any other rules like that? “Uh, yeah. But I don’t know if I want to say ’em.”

Oh, go on.

“No,” she laughs. “They’re fetishes, mainly. Just pure fetish. But we’re in a position to demand our fetishes and get them. No-one ever complains. People say, ‘If you join their band you’ll be a slave to their whims.’ But what’s so bad about that? We have really good whims, so what’s wrong with being a slave to that? I would have loved that opportunity.”

For the early part of their career, Ivy played a Bill Lewis guitar – made in Vancouver, and perhaps most famous as the guitar David Gilmour used on much of Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon – that was broken after a security guard fell down some stairs with it after a gig in Paris.

From the mid-'80s onwards, she played a 1958 Gretsch 6120, with patent-applied-for Filter’Tron pickups and a Bigsby. Her standby guitar was a reissue Gretsch 6120 Junior with TV Jones pickups. Both are strung with D’Addario XL115 strings, .011-.049.

Some people say Gretsch guitars don’t stay in tune. Not Ivy; she insists that she has always had an understanding with hers. “Yeah, it’s uncanny how much mine does stay in tune,” she says.

“People say they can’t believe it. I think it’s a psychic relationship I have with it. An agreement. Sometimes it’s hard to keep in tune if it’s cold, and studios are cold, unfortunately, so I get tuning problems there. We did a show at London’s Brixton Academy once and I couldn’t stay in tune through one song because it was freezing. But if it’s warm enough, that guitar will just work with me. And, uh [stern voice], it’d better. We have an understanding.”

Live, she used a Blackface Fender Twin Reverb. “But in the studio I like to record with small amps, just totally cranked.” It was something she learned from British guitarist Chris Spedding, who produced the band’s first demos.

“It’s not really good to fill the room with sound leaking,” she says. “It’s better to have a small amp with a good sound. I have this beautiful-sounding Valco amp. Valco made National and Supro, evolved out of Chicago. Just one 10-inch speaker, beautiful reverb and tremolo, and I’ve been using that at least since [1990’s] Stay Sick!”

The Cramps made eight studio albums and one classic live album (1983’s Smell of Female), but their career was dogged by record company politics. 1986’s career high point A Date with Elvis – a delirious, hilarious album on which Ivy played all the guitars and bass, and produced it too – didn’t come out in the US until 1990.

Flamejob [1994] came out on Creation Records and was buried as founder Alan McGee had a drugs-induced breakdown and their new signings, Oasis, went stratospheric. (“Creation crapped on us,” Ivy says. In what way? “In every way.”)

Early co-guitarists like Bryan Gregory and Kid Congo Powers got more credit than they were due, even though Gregory was really employed for his looks. He couldn’t tune his guitar and would wander over to Ivy’s side of the stage for her to help out.

“Bryan was mainly more of a visual thing. It’s hard to say what he brought, guitar-wise. I had to do a lot of his parts on the albums, simply because he wouldn’t even show up.

“Kid Congo had a unique style,” she says. “On that first Gun Club album [Editor’s Note: The Cramps poached Kid Congo from Cramps-inspired LA rockers the Gun Club], Ward Dot-son’s the guitarist, and he’s so good, but the parts he’s playing were parts that the Kid was doing in the Gun Club. But again he was someone who couldn’t tune his guitar.”

The album that turned out to be their last – 2003’s Fiends of Dope Island — featured a classic sign-off from Lux, a song called Elvis Fucking Christ that was borne out of the two of them at home watching a music-awards show. “The big rock awards / Crowned a brand-new king,” go the lyrics. “It shoulda been me instead / Don’t they know that I’m Elvis Fucking Christ?”

“We were watching some awards show and Lux was like, ‘Aw, you’re kidding! If those guys are the kings of rock ’n’ roll then I must be Elvis fucking Christ!’”

He was, too. The guy could eat up a stage. “It goes back to the rock ’n’ roll tradition of boasting – like Bo Diddley and Howlin’ Wolf,” she says. “It’s a blues tradition to boast about yourself that you’re the king, with the biggest dick, the biggest queen, whatever.”

The king might be dead, but the Queen of Rock ’n’ Roll is still out there somewhere. Ma’am, we salute you.

Scott is the Content Director of Music at Future plc, responsible for the editorial strategy of online and print brands like Guitar World, Guitar Player, Total Guitar, Louder, Classic Rock, Metal Hammer, Prog, Guitarist and more. He was Editor in Chief of Classic Rock for 10 years and, before that, the Editor of Total Guitar and Bassist magazines. Scott regularly appears on Classic Rock’s podcast, The 20 Million Club, and was the writer/researcher on 2017’s Mick Ronson documentary Beside Bowie.

“I suppose I felt that I deserved it for the amount of seriousness that I’d put into it. My head was huge!” “Clapton is God” graffiti made him a guitar legend when he was barely 20 – he says he was far from uncomfortable with the adulation at the time

“I was in a frenzy about it being trapped and burnt up. I knew I'd never be able to replace it”: After being pulled from the wreckage of a car crash, John Sykes ran back to his burning vehicle to save his beloved '76 Les Paul