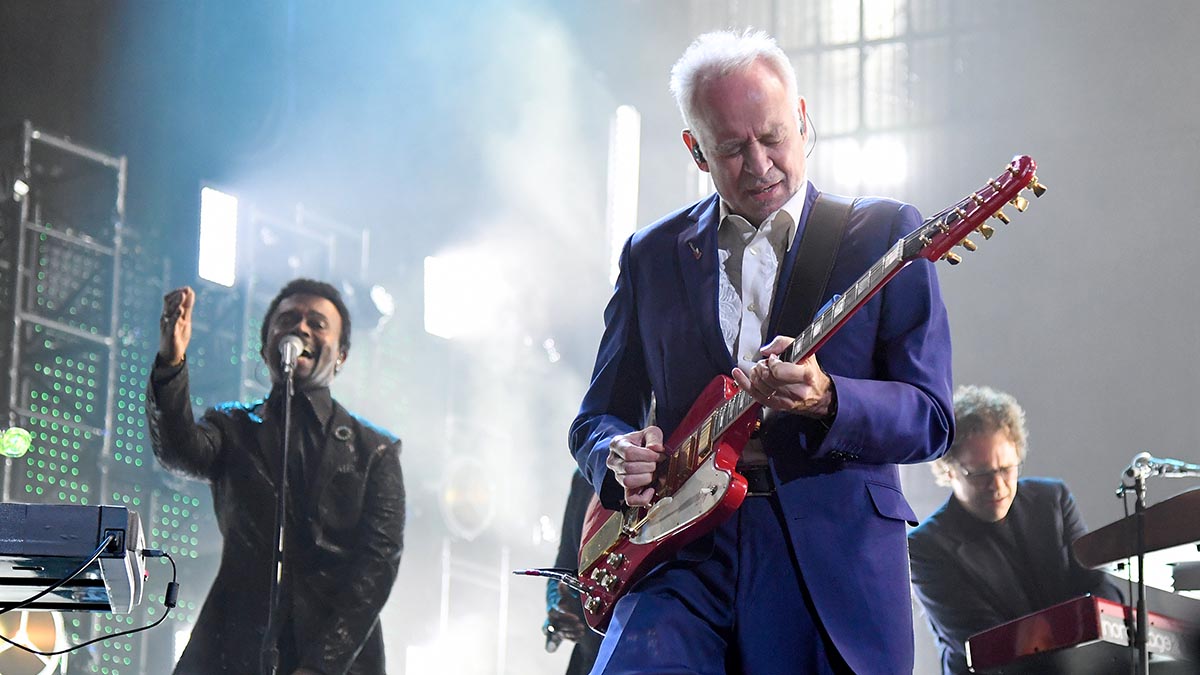

Phil Manzanera: “I didn’t really want an incredible technique: I thought that would impede my ability to enjoy music for the whole of my life”

The Roxy Music icon on home recording, the art of songwriting and the limits of technicality

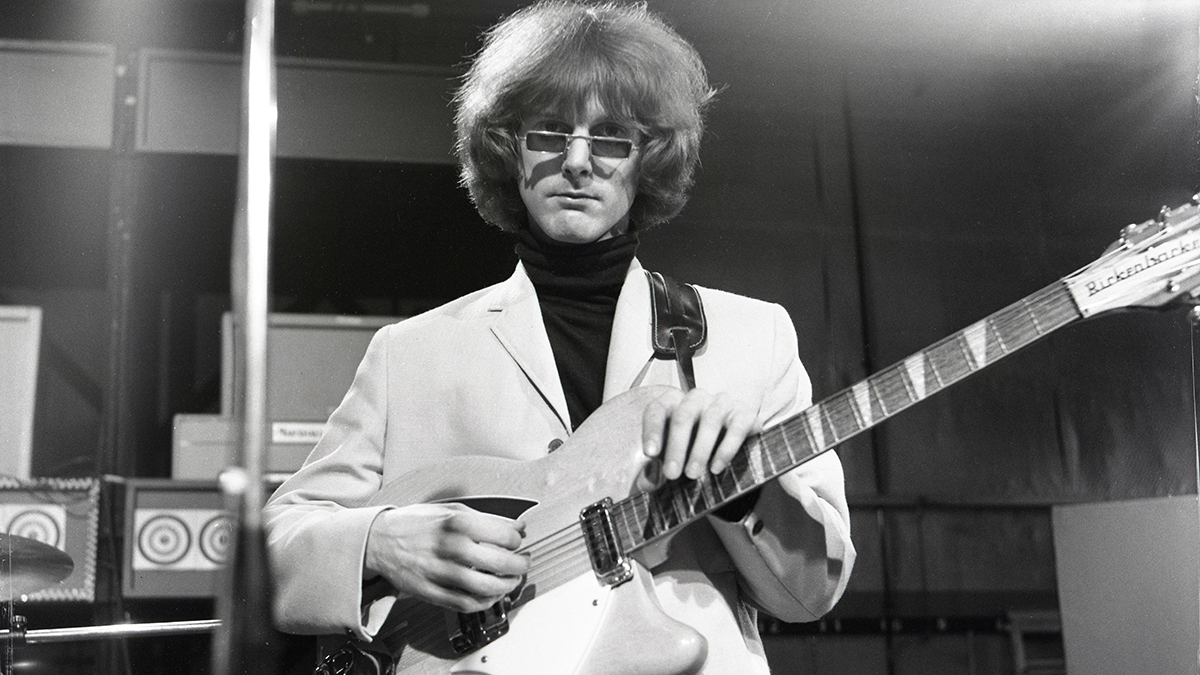

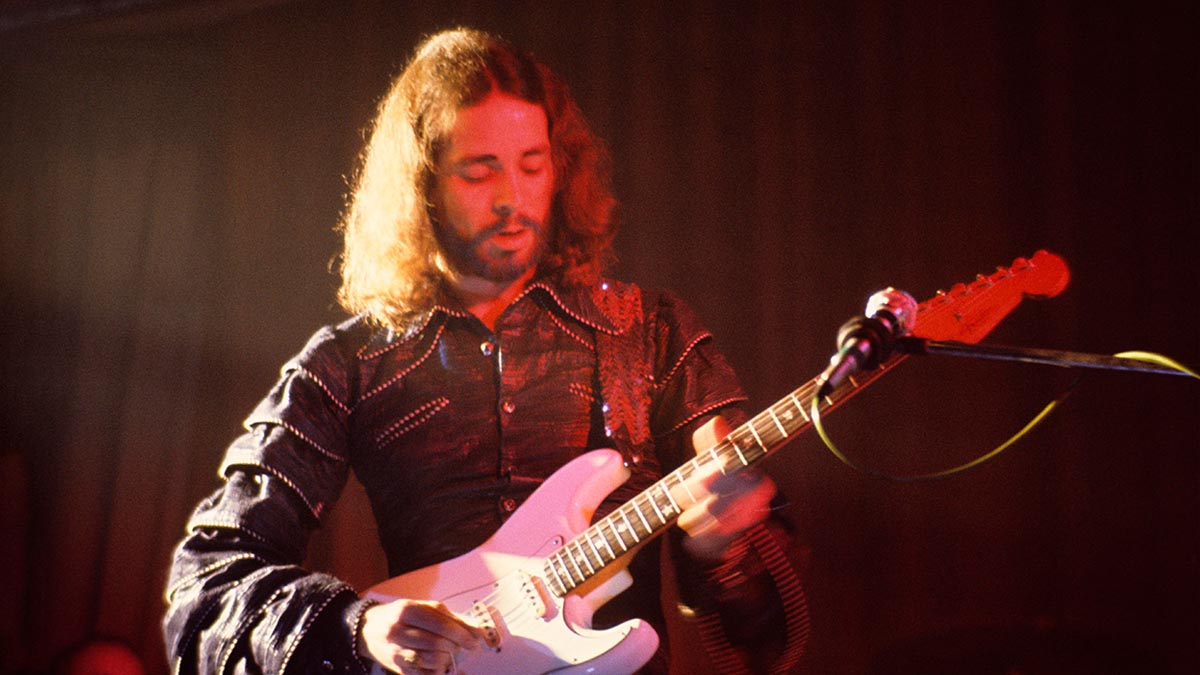

In Roxy Music, Phil Manzanera was the guitarist who put the addictive hooks into hits such as Love Is The Drug and Angel Eyes. A lifelong sonic innovator, Phil worked closely with Brian Eno to create Roxy Music’s experimental pop classics of the 70s – but Roxy’s albums also showed him to be a player of rare taste and poise.

Phil’s also produced albums as diverse as David Gilmour’s On An Island and John Cale’s Fear – but he’s far from done making his own music. In fact, he’s just completed a new album entitled Caught By The Heart with Tim Finn, formerly of Crowded House and Split Enz. A multi-layered melange of sound with a Latin heartbeat, it brims with soulful sounds from all corners of the world.

Despite its eclecticism, Caught By The Heart was recorded while both Phil and Tim were confined to their home studios, separated by thousands of miles, during lockdown.

With the album now out and the music world slowly emerging from the long shadow of Covid, we joined Phil in the ‘hut’ that became his musical sanctuary to hear his perspectives on the art of recording, learn how he crafted Roxy’s timeless guitar lines, and find out what guitar gear has captured his heart in recent times.

How did you first meet Tim Finn?

“Well, we first met in 1975 when we were on the first Roxy Music tour of Australia. We just arrived in Sydney after a humongous long journey. In those days, it seemed really like a huge adventure to go to Australia. And so I spent 24 hours or something in a plane, I got into my hotel room and collapsed on the bed, turned on the telly and the first people I see are Split Enz.

“And it wasn’t what I was expecting. I don’t know what I was expecting, actually, just some sort of weird folk music or something. And I thought, ‘Who the hell are these freaks?’ I found out later that they’d come over from New Zealand and that was their first appearance on the telly. And so I thought, ‘Wow, that’s great.’ So then I go to the Hordern Pavilion, which is where we were going to play the next day, and they’re our support act! Couldn’t believe it…

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“So I just watched them from the side on stage. Then, when they came off, I went past the dressing and said, ‘Hey, guys, wow, that was great – anything I can do to help?’ and a little head popped out and said, ‘Will you produce our first album?’ And I thought, ‘Oh really? And how’s that going to happen?’ And, in fact, they did go on and record their first album in Sydney, I think. But then, bizarrely, they came to England and we re-recorded it with some new tracks in Basing Street Studios in London in ’76, I think it was.”

How did you come to work on this album with Tim?

“I bumped into Tim’s brother Neil at the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame a couple of years ago when Roxy was being inducted, and we had our picture taken. I sent it to Tim and said, ‘Look who I found in New York…’ and then we started conversing over email and then suddenly, you know, lockdown happened.

“I’m in a little home studio an hour and a half from London, in West Sussex. I’m in this little hut and my screensaver is an island in the Pacific. And suddenly an email pops up from a guy [Tim] on an island in the Pacific saying, ‘Have you got any slow Latin grooves that I can write stuff to?’ And I was actually preparing an album, a Latin sort of album. So by complete happenstance, I said, ‘Well, yes, I’ve got a whole bunch of stuff.’

“So I went through my Logic sessions and thought, ‘Well, I wonder if this would be any good?’ Then I’d send something to him and, because of the time difference, by the time I go to bed he’s received what I sent him. He would then put stuff on it, send it back, then I’d wake up and marvel at what he’d done – because he really is incredibly good at songwriting and singing. I mean, literally, I’d send him a backing track and it’d come back the next day with singing and words on it. I’ve never been in a process like that before.”

Almost sounds like a game of chess, where each player makes a move and then waits for the other to take their turn – what are your feelings about working that way?

“What was interesting this time was working with somebody who is on par with you because you’re not going to get away with everything you might otherwise do. All musicians think that what they do is absolutely brilliant. But you need somebody to say, ‘Hmm, could you try a little bit harder?’

“And, you know, occasionally Tim, in the nicest possible way, would say that to me and I’d think ‘Oh, damn! I thought that was fine.’ [Laughs] But, you know, he made me work a bit harder. He was always right, actually. So it was me and Tim sending stuff backwards and forwards.

All musicians think that what they do is absolutely brilliant. But you need somebody to say, ‘Hmm, could you try a little bit harder?’

“But there was also this other person, a proper engineer, who’s on his computer in Greenwich or somewhere – and that was Mike Boddy, who is almost like the third person in this relationship. He really is very important because there’s a lot of technical stuff that I create, which is a mess, quite frankly. And he has to then sort it out and he has to improve everything that me and Tim do sonically because he’s got the most amazing plug-ins and stuff like that…

“I never claimed to be a hands-on producer, tweaking the desk. I am definitely from the George Martin school of thinking conceptually: ‘What’s this song about?’ I don’t want to be twiddling the knobs, although I’ve sort of had to, to a certain extent. But I’ve kept it very simple, my recording process here in my room, you know? I do have a studio in London – but I’ve only been there once in 18 months. I’m very happy in my little room.”

Modern recording tech allows musicians to create really powerful studios in their own homes. Does this render the large studio approach obsolete, do you think?

“Well, I always thought that there is no one-stop solution to the whole recording process. Having gone from a time when everything was analogue to sitting in front of a computer with endless possibilities of tracks, I can say they’ve all got the good points and bad points.

“Roxy never really wrote a complete song and then performed it in the studio because we couldn’t write like the [career] songwriters. So it was always: record backing tracks, get them overdubbed and then give it to Brian and he would try and write the top line for it. In some ways, it was very much like the modern way of doing stuff now.

Roxy never really wrote a complete song and then performed it in the studio because we couldn’t write like the career songwriters

“But if you’ve got a band and you’ve been together for some time, and you create something special by all playing together, then that is fantastic. But if there is a weak element in that band then that’s a problem. If you’re all playing together and you think, ‘Oh, the drummer’s not playing in time…’ it’s like, ‘Oh, no, what are we going to do here?’ Over the years I’ve done all sorts of crazy things trying to keep a drummer in time before they invented click tracks.

“So recording is very much an accumulation of all sorts of recording practices over the years. But at the end of the day, you’re serving the song and you’re trying to get across what the song is about so that it resonates with the listener.”

Your guitar lines on the Roxy albums are masterpieces in terms of being instantly memorable, but never more than the song required. How did you develop that knack?

“I’ll tell you what it is. If you’ve grown up loving George Harrison, The Beatles, you know that every single guitar part or almost every part on every Beatles song is absolutely the best one. And if you listen back to the different takes and different versions of the songs they went through until they reached the one that we all heard, it is amazing how they got there. They got the right sound and the right guitar part in the right place on each song.

“Well, I was very lucky to have Chris Thomas as a Roxy producer in 1973. Chris Thomas was the assistant producer with George Martin for The Beatles. So we sort of learned about part-playing, if you like, from Chris Thomas, which he learned from George Martin.

“The British tradition, Abbey Road style... on your first couple of times in the studio you had that drilled into you by the top person. It stays with you, you know? But then combine that with working with Brian Eno and you get a mixture of the traditional Beatles-type stuff and Eno, where it’s like anything goes.

“Try the craziest thing, you know? I used to love Miles Davis as well – I loved the economy and the tone of what he was into. It’s almost like an artist, just putting one dab of colour somewhere in the painting.

“And so context became important to me because Roxy was all about the musical context, the world that we created behind Brian Ferry for his weird voice. Also, I didn’t have – and still don’t have – incredible technique. I didn’t really want an incredible technique: I thought that would impede my ability to enjoy music for the whole of my life. When I was like 17 or 18, I thought, ‘I’m just going to spread it out.’ So I really like listening to people who have got incredible technique, but I don’t want to do that myself.”

I didn’t really want an incredible technique: I thought that would impede my ability to enjoy music for the whole of my life

We’ve often said if you want your solos to be remembered, play fewer notes...

“Yeah, I think you’re right. ‘Less is more’ is the phrase. It’s like the choice of where you put the note, when, and with what sound can have a great resonance with people. They hear something that really gets to them sonically. And you have to sort of keep your nerve.

“To start with in Roxy I got a bit frustrated because people would say, ‘Well, there’s no guitar on this,’ because I was doing that weird kind of guitar that had been treated by Brian Eno [laughs] and I was thinking, ‘Hang on! I am playing guitar.’ So I ended up thinking that I’d eventually have to play something flashy because I’m not getting any recognition here! So there was always that pull [towards flashy playing], but I think I sort of resisted it.”

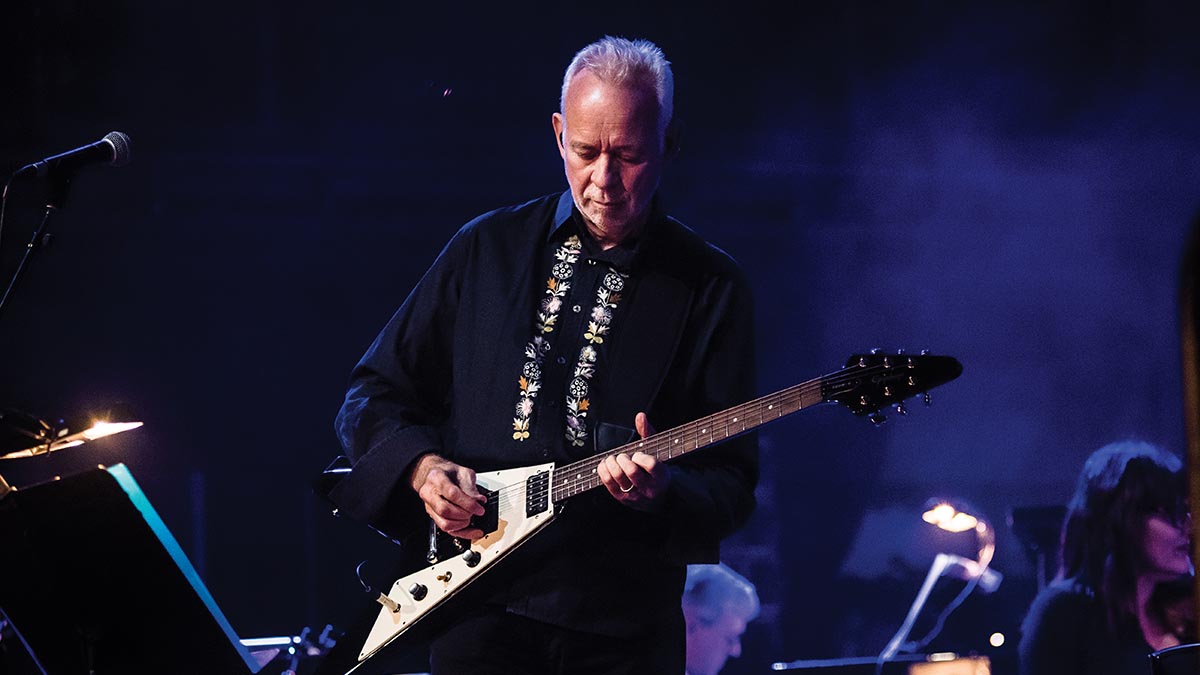

What was your recording rig for Caught By The Heart?

“I’ve got the studio up in London where I’ve got all the amps I’ve ever had, every fuzzbox you can imagine, delays – all that. But for this album and for everything I’ve done in the last 18 months, it’s been one Shure SM57 microphone, six inches away from a little Fender Pro Junior amp, which is linked up to Universal Audio Ox [Amp Top Box, a reactive load box].

“I used four main guitars on the album: I’ve got my red 1965 Firebird, the one that I’m most identified with; I’ve got a ’51 Telecaster; I’ve got a sort of 90s Strat; and I’ve got an Epiphone Flying V. And then I’ve also got a nice Spanish guitar and a Cuban guitar, which is the first guitar I ever learned guitar on in 1957 – a Spanish guitar from Cuba. That’s all I used.

“What I found was that this simple setup using the Ox brought out the qualities of these guitars. They sounded better than they’ve ever sounded before. I remember times in the studio... taking hours with Hiwatt 4x12s and things, and using this or that amp… But this time, for some reason, I just plugged straight in [to the Ox] and they sound like they’re meant to sound, these great guitars.”

“What I would always do is record one track totally without anything on, clean. And then if I needed to have echoes or any other weirdness that I wanted, I would use the plug-ins on Logic on another track and then blend the two together. And it’s forced me to try harder with just the basics and anything that’s lying around. I’ve got, like, a fountain pen here, which tends to be my slide or for doing weird sounds and bouncing it off the strings or whatever with them.

I will go through each take and just pick out any bits that sound good. So I’m left with this sort of patchwork quilt on the screen – and that’s the craft

“All my tricks that I’ve learned over the years are in these tracks. And if I did something and it wasn’t quite right, Tim might say, ‘Mmm, that’s not quite the sound…’ I’d try it again, however many times and eventually I’d get one and he’d say, ‘Yeah, that’s it.’ Thank God! So it has simplified things a lot, if you like.

“It’s actually been a lot more satisfying than the hours and hours I’ve spent not only in the studio trying to get sounds but also when I’m producing other people, where they would play a solo for a week or so [laughs]. I try not to do that.

“Also what I do is I will play intuitively. I’ll put the track on and I’ll play it 20 times. Then I will go through each take and just pick out any bits that sound good. So I’m left with this sort of patchwork quilt on the screen – and that’s the craft part of it. But I’m very happy with the sound that I’ve got out of these few guitars.”

The reverbs on the album are beautiful – what did you use?

“Well, I tell you what, on this Universal Ox, there are hundreds of different combinations of reverb and amps and mics and all sorts of things. So it’s sort of a double process, really. You’ve got the initial sound, you’ve got the Ox sound and then I would use the whatever in Logic… and then Mike Boddy will use anything that he fancies if he thinks it needs a little tweak as well.

“He knows what I like. I mean, if I was up in my studio then I’d probably be using my Roland Space Echo that I’ve used on almost everything I’ve ever done. I’ve got my original ones there and I’ve got my original Revox that I used to get real tape-echo from.

“As technology developed since 1972, I’ve been there at the forefront, whether that was with Eno or whatever – I’d be using the new equipment as it came out and everything like that. But now I’ve sort of pared it down to the essentials.

“One thing is a great tube amp, a simple one, with maybe a 10- or 12-inch speaker and a cheap mic for the guitar. I mean, I’ve got a Neumann here, but I only use that on the Spanish guitar, not on the stuff coming out of the Fender. Actually, I also used a Carr amp to tell you the truth, which has been absolutely terrific: a Carr Mercury.”

What’s the best recording tip you’ve learned over the years?

“I would say when you approach a track, just play without thinking. Often, if somebody sends me a track I don’t even listen to it before I plug in and play. I just put it on and then just react to whatever’s there – because if you think about it too much you can just end up just playing your basic riffs that you have in your locker.

“So if someone asks me to play on something, I think, ‘Great, send it to me.’ I put it on, but I don’t listen to it at first, I just get all my guitar stuff ready and everything. And the minute it comes on I start playing and I have to quickly find which key it’s in or whatever. But sometimes that’s great because you end up playing something you never thought you were going to play.”

- Caught By The Heart is out now via Expression.

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.

“For years, the only 12-string acoustics I got my hands on, the necks always pulled off after a bit. I earned a lot of money replacing them!” Why one of the UK’s most prolific luthiers is a bolt-on acoustic die-hard

“It holds its own purely as a playable guitar. It’s really cool for the traveling musician – you can bring it on a flight and it fits beneath the seat”: Why Steve Stevens put his name to a foldable guitar