“I’ve had all of the great guitarists in the world say to me, ‘Pete, you’re not in the top 10 for virtuosity, but you’re certainly No. 1 as an acoustic rhythm player’”: Pete Townshend on Who’s Next, Lifehouse, and fun times with Superstrats

In this brand-new interview, the Who mastermind looks back on Who's Next, the grand designs of Lifehouse, and why he is still having fun on the guitar thanks in no small part to Charvel and Jackson

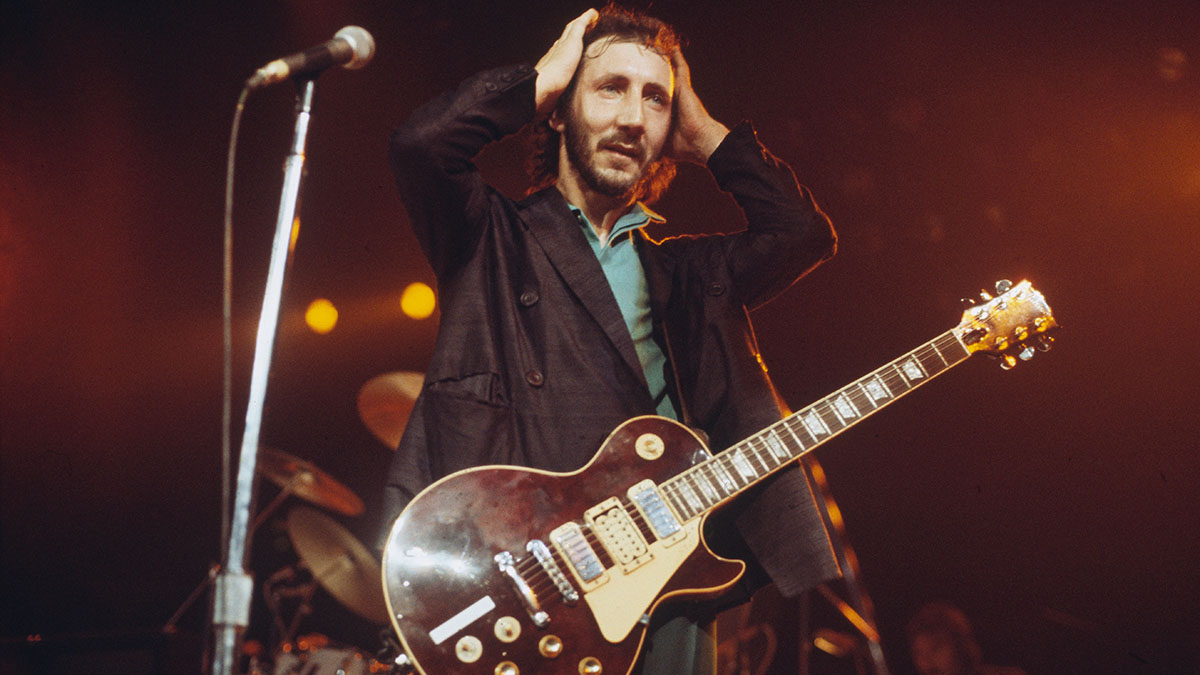

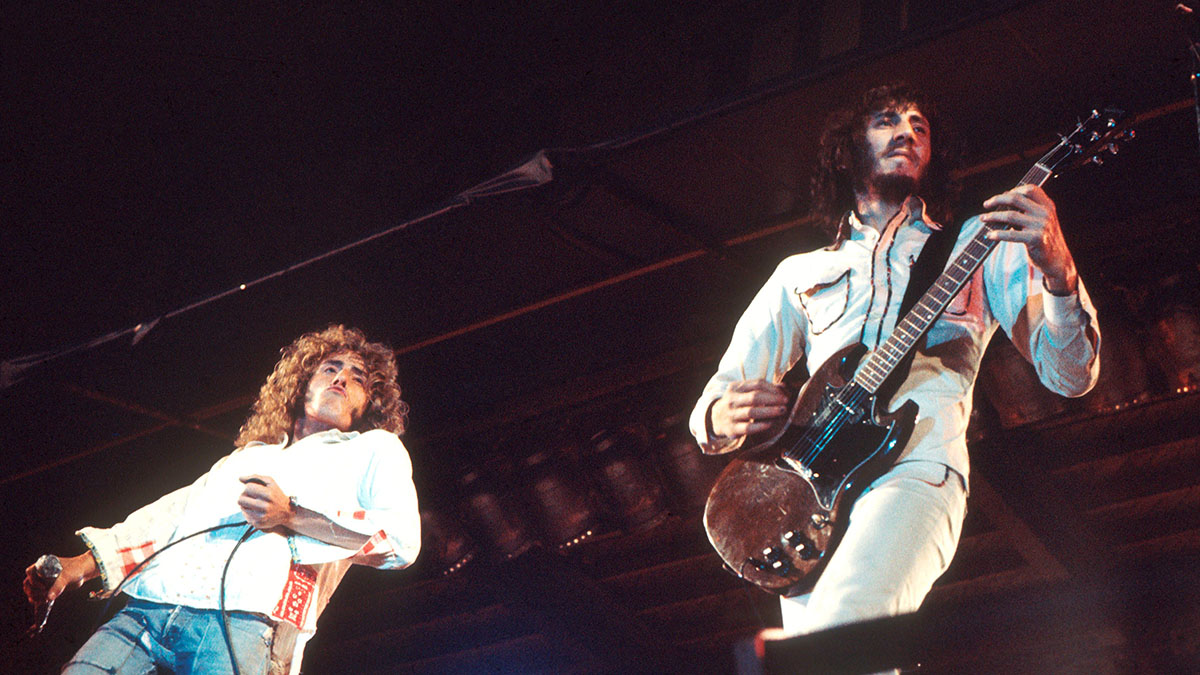

During the golden age of rock ’n’ roll, Pete Townshend helped define and redefine both the electric and acoustic guitar several times over. As the Who’s guitarist, he pioneered an aggressive, almost punky approach to the guitar in the mid-1960s, at least a decade before punk was a genre.

And his rampant destruction of his instrument on stage – which he later attributed to his studies at Ealing Art College of Gustav Metzger, the pioneer of auto-destructive art – became not just an expression of youthful angst but also a means of conveying ideas through musical performance.

“We advanced a new concept,” Townshend wrote in his memoir. “Destruction is art when set to music.”

It also set the Who apart from just about every one of their contemporaries, but most especially guitarists like Jimmy Page, Peter Green, and, of course, Townshend’s friend Eric Clapton, who were peddling an English version of American blues back to the country of its origin.

“No-one who saw the Who at that time could deny that they were the best live band going,” Richard Barnes, the Who’s biographer and Townshend’s flatmate at the time, recalled in 2021.

“Even the biggest Kinks fan, if the Kinks and the Who were both playing in town, would go see the Who over the Kinks. They were a real show when no-one else was putting on a show. And that catapulted them into that rarified company.”

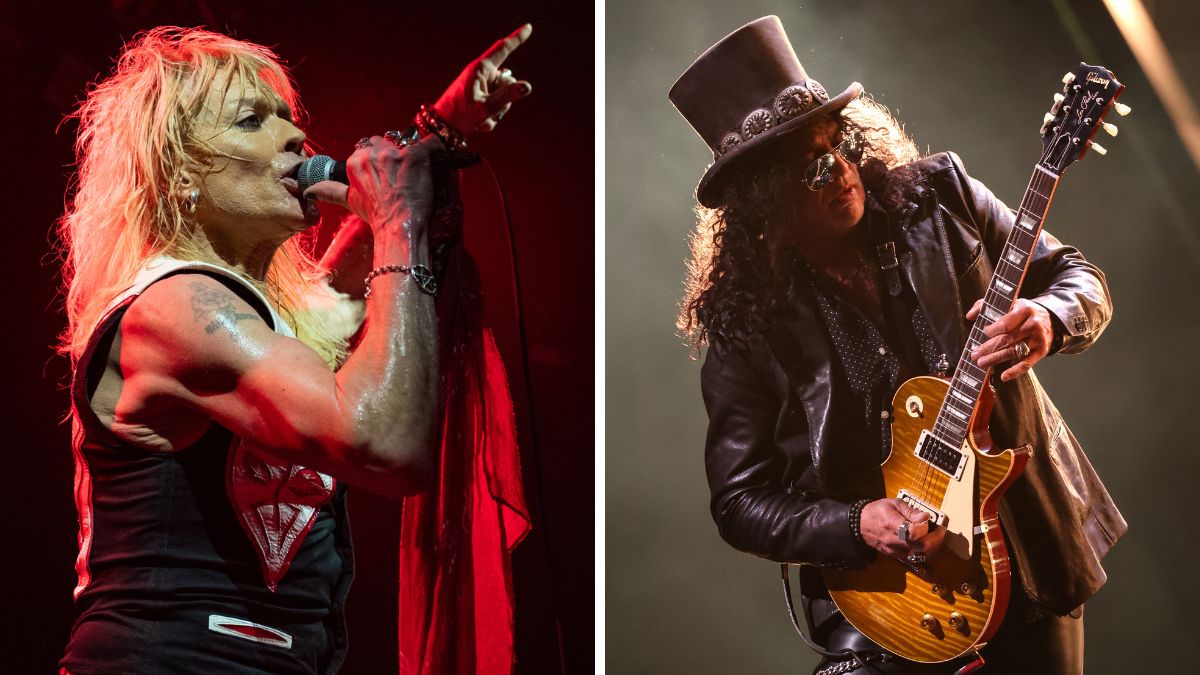

Townshend’s aggressive but melodic approach to the guitar, in a style that combined both lead and rhythm guitar, was hugely influential on guitarists from the Sex Pistols’ Steve Jones to Guns N’ Roses’ Slash, and many others.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Recently ranked No 37 on Rolling Stone’s 2023 list of 250 greatest guitarists of all time, he was also one of the first musicians to use large stacks of amplifiers and feedback as a musical tool, often ramming his guitar against the deafeningly loud speakers.

“Our managers signed Jimi Hendrix to their label and had me take him down to Jim Marshall’s,” Townshend told this writer in 1993, recalling a trip to the legendary amplifier designer’s shop. “At the time I had two cabinets of four speakers each. Jimi bought four cabinets. He didn’t do my act. He stole my act.”

“Pete Townshend is one of my greatest influences,” Rush’s Alex Lifeson, a guitar virtuoso in his own right, said of Townshend’s often underrated talent on the guitar. “More than any other guitarist, he taught me how to play rhythm guitar and demonstrated its importance, particularly in a three-piece band.”

And as an acoustic guitarist, Townshend’s staccato, cod-flamenco approach and precise rhythm – often doubled with an electric rhythm guitar that pushed and pulled against drummer Keith Moon’s brazen drumming – set a bar for players unmatched by anyone save, perhaps, Keith Richards of The Rolling Stones. It’s a style of playing born from necessity, as Townshend describes it.

“Keith had spent so long playing the drums, but not being a drummer, being a decorator, being an interpreter, being somebody that created energy around what I was doing, I became very metronomic,” Townshend tells Guitarist today. “I’m still very accurate.”

But it is also a style that owes a huge debt not just to the Who’s astonishing live performances of the era, but from Townshend’s groundbreaking use of home recording as a way to demo and perfect the songs he was writing for the Who.

As a result, Townshend’s songwriting developed in leaps and bounds from the aggressive pop of I Can’t Explain to the mini-opera A Quick One (While He’s Away), and full-blown operatic aspirations of Tommy, which broke the Who as international superstars.

Eventually came the peerless sophistication of the songs from Who’s Next, perhaps the greatest rock ’n’ roll album ever, as well as the rough elegance and power of Townshend’s greatest songwriting achievement, Quadrophenia, which took the rock opera as far as it could go.

“I’d got my first really proper 3M tape machine,” Townshend today recalls of that home studio‑slash-workshop. “And I was using Dolby. I was using Dolby before recording studios were using Dolby. It wasn’t innovation, it was just good luck. My company that made studios for people was based next to Dolby on Clapham in London, and so I knew Ray Dolby, and I could work on my 8-track, but I could also do loads and loads of dumping – combining tracks – so I could add more and more elements.”

Endurance Test

On a balmy October afternoon in France, Pete Townshend meets Guitarist to discuss Who’s Next, the Who album that has always, and probably will always, define the band. His piercing blue eyes hidden behind wraparound shades, at 78, Townshend is still as animated as ever when discussing – and defending – his band.

“I don’t think we’ve done a show since the '70s that didn’t include at least three or four songs from it,” Townshend says.

But Who’s Next is also the Who album that almost wasn’t. With his bandmates, not to mention management who also ran the Who’s record label, champing at the bit for a big, bold follow-up to Tommy, Townshend, in between dates on a relentless touring schedule, dug in at his home studio – a luxury that was unheard of at the time.

“It rivaled Abbey Road, technically,” he recalls, and started expanding his songwriting palette via the latest – though ridiculously crude – synthesizer technology. The results? Lifehouse.

Along with some of the best songs Townshend had ever written – Baba O’Riley, Behind Blue Eyes, Bargain, Going Mobile, and Won’t Get Fooled Again would all end up on Who’s Next, while Naked Eye, Pure And Easy, Too Much Of Anything, and a host of others would trickle out during the era – over a couple of days in September 1970, he also wrote a futuristic script that foretells a planet on the verge of ecological collapse, with a population locked into virtual reality suits controlled by autocratic rulers and pacified by an endless stream of mind-numbing content.

While that may sound pretty easily digestible, if not downright prescient, today, even in the wake of the moon landing and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, Townshend drew quizzical blanks from just about everyone he tried vainly to get onboard.

The fact that the plot twist came in the guise of rock ’n’ roll being outlawed, leading to a revolt and a stand-off at the Lifehouse, where music had allowed masses of people – who have ditched their “experience” suits – to congregate and merge into a single, universal mind, didn’t help matters.

More than 50 years later, Townshend is in some ways still chasing his dream of the Lifehouse project, as a massive new 11-disc boxset entitled Who’s Next | Life House proves, coming complete with a remastered Who’s Next, loads of Who tracks, and a raft of home demos from the era, plus a book by Townshend and Who experts Andy Neill and Matt Kent, and a graphic novel expanding the story of Lifehouse.

Along the way, Lifehouse was never far from Townshend’s mind. He nearly had a nervous breakdown during the early days of the project, barely sidestepping jumping out the window of the Manhattan hotel suite of one of his then managers, Kit Lambert.

And, after abandoning the Lifehouse project in favor of the nine-song single-LP Who’s Next album at producer Glyn Johns’ urging – plus Quadrophenia and an aborted rock opera called ‘Long Live Rock’ – Townshend enlisted the Who’s singer, and then au current movie star, Roger Daltrey, to revisit the Lifehouse script. Townshend fleshed out and updated the story with songs like Slip Kid, Who Are You, and Sister Disco – which would go on to become Who staples – before giving up again.

Finally, at the turn of the century, Townshend released the Lifehouse Chronicles boxset on his own Eel Pie label, which included home demos and even a radio play of Lifehouse and a book, and performed two shows in London that once and for all put the pieces of Townshend’s massive work into a cohesive narrative.

It’s basically just conceptual art. In other words, it’s just coming up with an idea, putting it on paper, and then it not happening. And for me, I’m perfectly happy with that idea

Still, like Brian Wilson’s aborted Smile and so many other great, lost rock albums, Lifehouse was really more an idea in Townshend’s head than anything else.

“You’re right that, like Smile, there’s a sense of there being a lost concept,” Townshend says. “Somebody wrote recently something that feels true but also feels sort of a little bit wonky, which is that Lifehouse, as it exists, is an unfinished project, both as an experiment between artist and audience but also as a story, and also as an integrated series of songs that helped to demonstrate and illustrate that story.

“It’s basically just conceptual art. In other words, it’s just coming up with an idea, putting it on paper, and then it not happening. And for me, I’m perfectly happy with that idea, but the fact is that there is no set of songs that tell the story. It’s a very poetic idea, and that has never really properly come across.

“So, I meet people in the street, and they say, ‘I love Tommy, I would listen to it when I was 13 years old, and it changed my life.’ And that happened again with Quadrophenia, of course. But that didn’t happen with Lifehouse because it wasn’t complete enough. It was just ideas that were unfinished.”

In fact, the Lifehouse recordings were strewn all over the place. There were songs on Who’s Next, several on the 1974 compilation album Odds & Sods, and across B-sides, like the fantastic Greyhound Girl on the flipside of Townshend’s 1980 hit, Let My Love Open The Door. But it wasn’t a cohesive project.

And, like Brian Wilson, Townshend had a serious mental breakdown during the making of what eventually became Who’s Next. The members of the Who were at their most band-like at the time, but the pressure on Townshend, as the creative force and visionary and spokesperson, was intense.

Meanwhile, he kept getting thwarted. Co-manager Kit Lambert wanted to make a Tommy movie – so there were competing projects – so Townshend didn’t have the man who had helped him realize the Tommy project. Very much on his own, even though he had a band that was functioning at its absolute peak, Townshend recalls his frustration as palpable.

As co-producer Glyn Johns recalls in his 2014 book, Sound Man, even as late as when he was brought on as producer, Townshend gave him not just a raft of demos but the script for Lifehouse. Townshend clearly hadn’t given up on his grand concept just yet.

“I was still hoping for a double-album,” he recalls. “It became a tough time. But it was also a very important lesson for me. I’d given up, in a sense, on the idea of working with Kit, which was a very big thing. I still had the band, and the band was still behind me. So when Glyn took over, I was hoping that he would make a double-album. That was all.

“That’s why I gave him the script. I sat down with him before, and he said, ‘I really don’t understand this at all.’ And I just remember saying to him, ‘Listen. I hope you don’t feel I’m insulting you, but you really don’t fucking need to. This is my project. Just do what you do.’

“I didn’t think that we would get to the end of the project and he would decide that the double-album was going to be a single album. And leave off Pure And Easy! I remember thinking that was like leaving Amazing Journey off Tommy. Because it’s the song that sets the scene; that gives the story its backbone.

Leave off ‘Pure And Easy’! I remember thinking that was like leaving ‘Amazing Journey’ off ‘Tommy.’ Because it’s the song that sets the scene; that gives the story its backbone

“Glyn chose The Song Is Over instead because it was a good closer to the album. He wasn’t thinking about Lifehouse, he was thinking about a bunch of songs, and he made the decision based on that. But I decided to trust his instincts and his intuition – because by the time we got to the end of the recording, it was clear that Kit was gone for me, and that there was no way I was going to rescue the movie side of the project.

“And also, the idea that I might be able to do anything technological with the band had drifted into space. But remember, what we had invented was the use of backing tapes. And they fucking worked! And they worked so well partly because of Keith Moon. He didn’t need a click. He was the click!”

Synth Horizons

Townshend’s pioneering use of synthesizers, set against that often sparse acoustic/electric combination, gave the Who a new sound to play with, one that was, again, unlike any of the band’s contemporaries.

“It gave us this extra harmonic and musical implementation because we were just a three-piece band,” Townshend explains. “We didn’t even have a keyboard player. So it enriched our sound. And it was very, very exciting.”

Although The Beatles had used a Moog on Abbey Road in 1969, when Townshend began writing the demos for what would become Who’s Next, the use of synthesizers was both unheard of and nigh on impossible.

“Chris Thomas was assigned to help George Harrison figure out how to use the damn thing,” Townshend says with a laugh, recalling those early synths to be large, unwieldy things. But Townshend was looking to augment the spare yet still relatively grand, guitar-based demos he was concocting.

“When I got my first little EMS box, one of the first things I thought is, ‘I can play flutes, I can play clarinets, I can play trumpets!’” he recalls. “They’re funny little noises. But I wasn’t thinking about East Coast type [or] Don Buchla, mad electronic music, or even the electronic music that I’d been listening to by people like Malcolm Cecil and Morton Subotnick and people like that.

“Or Terry Riley, which was astral, ecstatic, uplifting music. Or Subotnick, which was interesting and sometimes rhythmic. Instead, I discovered that these little machines allowed me to experiment with melody. Plus, I also had a Lowrey organ, rather than a Hammond, which people in rock loved so much, and all made exactly the same sounds.

“Only Garth Hudson of the Band played a Lowrey. And I had a Lowrey, and it made all these little thin trumpet sounds and little thin violin sounds. Baba O’Riley came from the marimba sound that was built into the Lowrey Berkshire that I owned at the time. So I was excited to have these tools, and I think that excitement translated into some pretty interesting stuff. I was on a real high.”

Set against the relatively dry Gretsch 6120 that Joe Walsh had gifted him, Baba O’Riley was duly turned into the epic show-stopper it was destined to be.

“I kept the drums dry, I kept the bass clicky, I used the Lowrey as a decorative machine, sometimes I got the Leslie going and swirled it a bit, but the guitar work was often an afterthought,” Townshend tells us. “On songs like Behind Blue Eyes, Bargain and Won’t Get Fooled Again, those songs began with guitar, and it’s just me strumming away. And I’ve always been really good at that.

“I don’t think I was any better or worse at that than I’d been on Pinball Wizard. My acoustic work – I’ve had all of the great guitarists in the world, all of the great virtuosos in the world, say to me, ‘Pete, you’re not in the Top 10 for virtuosity, but you’re certainly No. 1 as an acoustic rhythm player.’ So, in a sense, that’s something that just happened to me because I was in a band with Keith Moon. I just had to hold it down. I had to be a metronomic, clear-cut, rhythmic player.”

Lifelong Love

Today, Townshend says he’s still enamored with the guitar, and points around the room at some of the instruments he’s been playing lately.

“I’ve got a Collings mandolin,” he says, gesturing. “I’ve got a Fylde Ariel, an old Jazzmaster from 1958 – one of the first – a brand-new short-scale Jaguar bass from Fender, which is incredibly good, a Guild 12-string, which is extraordinary and stays in tune over time, and I’ve got a J-200. And that will do me for here, this little studio that I have in France that I visit occasionally. I feel incredibly spoiled.”

So how has Townshend’s relationship with the guitar as a creative tool changed over time? And does he still have a sense of possibility in the instrument?

“Definitely!” he replies, emphatically. “What I’m happy about is that I can do two days of practice and learn some really flashy runs if I want to, though I’m still stuck with the old order, which is trying to make sure that I don’t let my fingers play a series of clichés.

I remember Leslie West saying to me about Eric Clapton: ‘I prefer your licks, Pete, to Eric’s, because Eric seems to be playing things that he’s learned, that he’s picked up from other blues players’

“I remember Leslie West saying to me about Eric Clapton: ‘I prefer your licks, Pete, to Eric’s, because Eric seems to be playing things that he’s learned, that he’s picked up from other blues players. And I think that is a fair comparison, although I have seen Eric play live, where he really goes sky high.

“I think one of the things that all guitar players of today are intimidated by is these young guys on Instagram that shred to hell and back, or to heaven and back, I should say, who started when they were six. But we are just our fingers.

“So the Who have just done a tour of the UK, and I don’t expect people to go on YouTube and get their minds blown, but I do think that some of the playing, some of the solos, some of the chordwork, some of the surprises, some of the avoiding tricks and being willing to take risks is really what I still feel the guitar is great for.”

Of course, most people know Townshend as a songwriter, or perhaps as the flamboyant, high-jumping, guitar-smashing showman of the Who’s heyday. But while he’s no virtuoso, Townshend is a peerless rhythm player who’s made an indelible mark on guitarists of all stripes over the past 60 years. So, what’s his latest guitar discovery?

The other day, I thought, ‘It’s time for me to try a Charvel, or one of these sort of heavy metal guitars’

“The other day, I thought, ‘It’s time for me to try a Charvel, or one of these sort of heavy metal guitars,’” he confesses. “I’ve stuck with Eric Clapton-style Strats for such a long time now, though I do pick up Les Pauls and SGs and I love them, but they don’t allow me enough scope and change on stage.

“So I’ve always thought, ‘If I buy a Charvel or a PRS or any of those super-fast new jazz guitars, I’m going to have one sound and it’s going to be finger memory.’ But the other day, I thought, ‘Fuck it. I’ll try one out.’ I bought a Jackson. I didn’t know that they were owned by Charvel and that Charvel is now owned by Fender, but I bought a Jackson.

“I got it out of the box and it’s got very light strings on and a notch where the strings are locked down, and it’s got the strings locked at the other end, too, and you tune them with little buttons. And so, the whammy bar is extraordinary!

“I was playing faster. No question. I was playing at three times the speed that I normally play at. And when I did fingering, drumming, it didn’t stop. It didn’t go thunk; it went ding. Because these guitars are built for a particular kind of thing. So I’m still learning and I’m still having fun with guitars.”

And does he still collect? “I had [guitar tech] Alan Rogan in my life for so long, and whenever we finished a tour, he would always buy me a guitar,” Townshend recalls. “And, of course, he bought me and gave me some fantastic guitars. I’ve never been really that interested in owning a ’57 Les Paul or anything. I picked up a few in my life and thought, ‘What’s the story here?’ Because what’s important about guitars is that they need to be played, and I think, unfortunately, it’s difficult to play them all properly.

“They need to be played to stay alive. Japanese guitars, particularly the old Yamaha 12-strings, when you bought them from the store, they were terrible. Now, they’re really good. Sometimes people don’t get it, but the wood has dried out. So, while none of us will seriously do this, we probably shouldn’t buy or own more guitars than we can play.”

I’ve kind of got to the point now where, when I pick up a guitar, I have to do a Joni Mitchell. I have to tune the guitar up to something that is completely illogical and then find something new in it

As for acoustic guitar, Townshend is, as always, pushing at its limitations.

“I’ve kind of got to the point now where, when I pick up a guitar, I have to do a Joni Mitchell,” he explains. “I have to tune the guitar up to something that is completely illogical and then find something new in it, because, even if you go into the jazz chord book, it may be a little bit richer than the four or five chords that are part of the legacy of rock, but you’re still limited.

“So it’s interesting that a song like Girl from Ipanema, which is a guitar song, is only a few major 7th chords. A lot of the chords are just major chords and minor chords pushed up together in an interesting way.

“So the discovery in the work with guitar can be about chords, it can be about composition, it can be about harmony, it can be about shredding. But the thing about shredding is that thing about letting your fingers do the work. It’s difficult when you’ve watched, for example, some of the great shredders performing live, and they look disconnected.

So the discovery in the work with guitar can be about chords, it can be about composition, it can be about harmony, it can be about shredding

“You think, ‘Are they really playing this or are their fingers playing it?’ In a way, if their fingers are playing it, that’s okay because then what they’re doing is they’re listening. They’re not playing, they’re listening, and that creates another sort of interesting fact about what’s called ‘found music,’ when we sample and we listen to music and we’re inspired by it because we’re listening.

“Keith Moon was a nutty drummer, but he listened. John Entwistle, too. So they were a very formidable rhythm section. And I knew I could play anything and they would follow. John Entwistle would know the notes that I was playing sometimes before I did! So the importance of listening is vital.”

So, does Townshend think that, since those speed players are less listening, more performing, that’s why there’s less of a lyrical nature to that speed playing? Or is it the nature of the beast, that if you’re playing that fast, it’s hard to be melodic and lyrical?

“Well, Prince could shred and he often would play a really soulful blues track, and then in order to get from one bit of blues to the other, he would do an extraordinary shred,” Townshend counters, emphatically. “So it was a bit flashy [vocalizing]. Maybe it was just to show he could do it. So, I don’t know. I think it’s just the disconnect that has happened sometimes.

“And where you see it stop is when that kind of artist, and there are many on Instagram – one of my favorites is a guy called Angel Vivaldi, who’s a brilliant, brilliant player – but when he works with other musicians, he changes. He actually listens to them and fits in. He can play anything that he wants to play. And there are a couple of others that I follow as well, but a lot of them are just solo musicians that have mastered their craft and got really, really fast.

“So, I think what needs to happen is they need to be fitted into the music world, somewhere other than Instagram. That’s the challenge for them. I think it’s the challenge right now, as it is for a lot of electronic music musicians: they are very isolated, working on their own.”

As we wind up our hours-long chat about all things the Who, Lifehouse, expanding guitar music by way of synthesizers, and the guitar itself, Guitarist asks Townshend to reflect on his 60-year love affair with the instrument that made him a household name.

“I swing my arm 15 times, I have an adrenaline rush, and I just let my fingers fly,” he says of his approach, even to this day. “But I go back to Live At Leeds and I’m all over the place. I watch my hands and go, ‘Fucking hell.’ Because most of it is bum notes, but it’s also incredibly powerful stuff. So I’m enjoying learning to both appreciate and play the guitar, still, to this day. Because you never stop learning. So, yes, I still love the instrument and, yes, I still have hundreds. I mean, literally!”

- Who's Next | Lifehouse Chronicles is out now via Geffen.

“Last time we were here, in ’89, we played with Slash on this stage. I don't remember what we did...” Slash makes surprise appearance at former Hanoi Rocks singer Michael Monroe's show at the Whisky a Go Go

“I’m inspired”: John Mayer has been spotted playing a Neural DSP Quad Cortex live for the first time – could this be his new amp modeler of choice?

![John Mayer and Bob Weir [left] of Dead & Company photographed against a grey background. Mayer wears a blue overshirt and has his signature Silver Sky on his shoulder. Weir wears grey and a bolo tie.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/C6niSAybzVCHoYcpJ8ZZgE.jpg)

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)