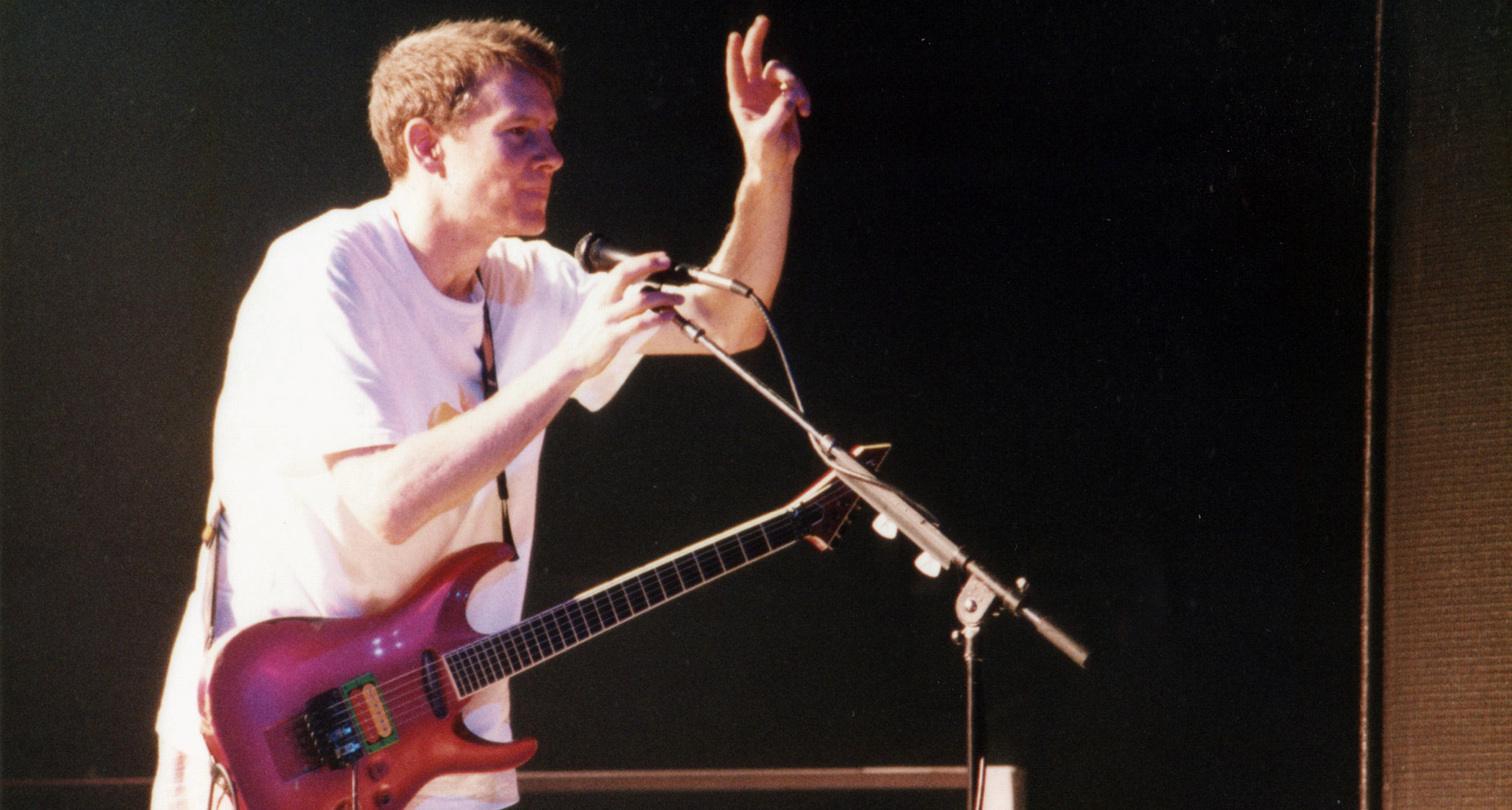

“Everybody was trying to make money off us, and we were oblivious. I thought everybody understood what we were doing. We weren’t trying to be Nirvana”: Page Hamilton on Helmet’s 1994 classic Betty – the unsung curveball the critics tried to kill

After the claustrophobic intensity of Meantime, Hamilton opened up the doors and chased down different sounds on album number three. No one was ready for Betty

In 1992, Page Hamilton appeared to have won the music lottery. The jazz-trained guitarist’s alt-metal/post-hardcore band, Helmet, darlings of the New York City downtown music scene, had signed a whopper of a deal with Interscope Records (worth a reported $1.2 million, staggering numbers at the time) and released their major-label debut, Meantime, which went gold in a matter of months.

Helmet’s music was easy to digest: the guitar riffs and rhythms were brutal and direct, the grooves were pummeling and unrelenting, and Hamilton’s vocals were perfect if you were into the “Ozzy Osbourne as drill sergeant” thing.

It all worked like a charm. MTV played the video of the attack-mode single Unsung in regular rotation, and the band’s touring dance card was checked off for the next year.

Any other rocker would have pressed “repeat” for the follow-up record, but Hamilton had other ideas. The band’s 1994 album, Betty, packed a few sure-fire bangers, most notably Milquetoast and Wilma’s Rainbow, but the rampaging pace was dialed down throughout most of the record, and there were even forays into jazz and avant-garde funk. For buzz-cut headbangers lusting for the hard stuff, Betty felt soft.

“The funny thing is, everybody who slagged the record now thinks it’s great,” Hamilton says. “That’s happened so many times with me, especially with critics. They write a review and kill an album, and 10 years later they re-review it and say, ‘I was wrong.’

“Here’s what I believe: If you’re trying to repeat what you did last time because it was successful, that’s kind of weak. That’s why I’m such a fan of [the Replacements’] Paul Westerberg and [the Kinks’] Ray Davies. They made it okay to shoot yourself in the foot, as long as what you’re doing excites you. I’m not doing this to please an audience. I only try to please myself.”

Even though Meantime went gold, Helmet had signed to Interscope for a huge sum at the time. Was the label expecting platinum or double platinum? How much pressure did that put on you?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I never gave it a thought. I didn’t give it much thought when we signed, either. I remember talking to [Interscope co-founder] Jimmy Iovine around the holidays. I said, ‘We’re thinking of putting the album out sometime next year.’ He said, ‘Get into the studio as soon as you can and do it now.’ And I was like, ‘Oh, shit. I better finish these songs.’ Which I did.

“We went into the same studio where we did our first album, Strap It On, and worked with the same engineer, Wharton Tiers. The only difference was we had a larger budget, so we got Andy Wallace to mix. I loved him.

“People from the label would come around the studio and say things like, ‘This smells like another ...Teen Spirit,’ which was absurd. But I remember Jimmy saying, ‘I’ve worked with Tom Petty, Bruce Springsteen and U2. You have your own vocabulary that you came up with. I’m not going to tell you what to do.’ Nobody was doing what we were doing when we came out, and he got that.”

Was the label okay with you deciding to produce yourselves on Betty?

“They didn’t frown on it. After we had just won a fucking Grammy nomination and had a gold record, Jimmy Iovine asked me who was going to produce the new record. I said, ‘Uh, me.’ I thought we had done okay. We were on MTV and had sold something like 650,000 records.

“Before Betty, we did that song Just Another Victim with the House of Pain guys for the Judgment Night soundtrack. T-Ray remixed it, and the album went platinum, so our manager said, ‘Maybe we should have a hip-hop guy do the Helmet record. Let’s throw people a curve.’ I was open to it.

People tell me, ‘You’re a control freak.’ I’m like, ‘Yes, I am. So be it.’ I put in the time because it’s my music

“The problem was, T-Ray worked his own way. He made tracks and would have guys come in and write words over them. Whereas I write the words, I write the tracks, I sing the lead vocal, I play the lead guitar, and I write the arrangements. I do everything myself, and then my band turns it into music.

“T-Ray said to me, ‘Your shit is so together. I don’t have anything to do.’ And I was thinking, ‘Why are you here then? Why am I paying you money?’ He’s a sweetheart of a guy, and eventually we did some other stuff, but he comes from a different world. People tell me, ‘You’re a control freak.’ I’m like, ‘Yes, I am. So be it.’ I put in the time because it’s my music.”

How did you come to work with Butch Vig on Milquetoast?

“We had met when we did the Led Zeppelin tribute album, Encomium, with our old pal David Yow from the Jesus Lizard. I was a big fan of Killdozer and other things Butch produced. Of course, after he did Nevermind, everybody wanted him.

“But we hit it off and talked about working together. He had just finished the album with his own band Garbage, and he said, ‘It probably won’t do anything, so I’ll be available.’ Then the thing went multi-platinum, and he became unavailable! [Laughs]”

I loved working with Butch. I adore the guy... Every idea he had sounded fantastic.

Ultimately, Butch had time to work on that one tune with you.

“Right. And it came out on The Crow soundtrack, too. I loved working with Butch. I adore the guy. I remember he said, ‘How about a guitar dropout for the first verse?’ I was like, ‘Whoa, what a great idea!’ He said, ‘Let’s do a far-away vocal thing.’ Every idea he had sounded fantastic.

“He couldn’t do the whole album, which is probably for the best, because it would have been Butch Vig and Andy Wallace – the same people who did Nirvana. Don’t get me wrong: We loved Nirvana, and we were friends with them. We played together with their old drummer, Chad [Channing], and later with Dave Grohl, but we didn’t want to be Nirvana. We were a completely fucking different band.”

Before cutting Betty, your other guitarist, Pete Mengede, left.

“He was let go. Let me clarify a few things. We have some kind of non-disclosure agreement or whatever bullshit is probably passed at this point after he sued us. He was let go for reasons that are absolutely viable and significant, and I care for him as a former member of the band. But I knew at that point that I didn’t need him to play on the albums.

“There were songs that he’s not even on because I’m a much better guitar player than he is. I was writing stuff to my ability, not his. Early on it worked, and then it stopped working. We let him go and it turned into a big dramatic thing.

There were songs that Pete's not even on because I’m a much better guitar player than he is. I was writing stuff to my ability, not his

“Then Rob Echeverria came in. He was a really good guitarist and a great guy. It just got to the point where I was tired of holding another guitar player’s hand. Rob learned all the songs and played on Betty, but after a couple of years I said, ‘I don’t want to do this anymore.’ I need another guitarist live, but I don’t want to deal with anyone in the studio.

“So I let Rob go, and it was amicable, and then I read all this shit about how he quit to join Biohazard. I’m like, ‘Please. Leaving Helmet to join fucking Biohazard?’ And then he was like, ‘I got tired of playing math equations.’ I’m like, ‘Math equations? Give me a break. It’s not math equations, bro. It’s called groove.’”

What was your guitar setup on Betty?

“My ESP Horizon Custom. It was my first endorsement guitar that I paid $600 for, and they never charged me again. The amp was my Marshall JCM800 2204S. I believe I used a 1960s greenback Marshall cabinet, which I stupidly sold when the band broke up. I had found it in a pawn shop in Cleveland sometime in 1990.”

Did you use a different guitar and amp setup for the jazz number, your cover of Beautiful Love?

“I did. For that song, I used my 1986 Fender Super Champ, and the guitar was my 1986 Les Paul goldtop that I bought from Sam Ash in Queens. It was always my dream to have a goldtop, and I bought it when I was 19 and went into deep credit card debt.”

After Betty, the band didn’t release another album for three years. Was it a difficult period? Did you need to reassess and regroup?

“Yeah. We had gone from playing to 10 kids at CBGB or the Pyramid Club to headlining Roseland. Money changed everything. The other guys were chilling when they were home, but I was writing songs. They were like, ‘You’re getting more money than us,’ and I was like, ‘I’m spending months writing these songs for us, and I’m doing all this work that I love and have to do to not go crazy. But at the same time, I get compensated for that.’ That created tension.

Everybody was trying to make as much money off of us as they could, and we were oblivious

“Plus, we were constantly going and going. Everybody was trying to make as much money off of us as they could, and we were oblivious. We were like, ‘Yeah, great, okay. We’re playing, we’re touring.’ I look back on it now, and it’s like, ‘Yeah, milk these guys for all you can.’

“There were great people that I still respect and am still friends with, but there were a lot of shitheads that didn’t give a rat’s ass about us and didn’t know the first thing about our music. I thought everybody was getting it. I thought everybody understood what we were doing. We weren’t trying to be Nirvana. It’s never what I set out to do.”

- Betty is out now via Interscope.