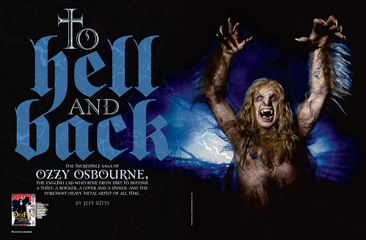

Ozzy Osbourne: To Hell and Back

The incredible saga of Ozzy Osbourne, the English lad who rose from dirt to become a thief, a rocker, a lover and a sinner—and the foremost heavy metal artist of all time.

Ozzy Osbourne was up shit’s creek. The onetime lead singer of metal superstars Black Sabbath had been fired by that band in 1978, and now, just one year later, the man who gave the world such classics as “War Pigs” and “Paranoid” couldn’t get even a nibble from the record companies. Ozzy looked washed up. But all that was about to change.

Rejected by nearly every label, Osbourne finally found a supporter in CBS Records executive Tony Martell, who immediately signed him to a contract. Unfortunately, among CBS execs, Martell was pretty much alone in his enthusiasm for Ozzy. Sensing the company’s disinterest, Sharon Osbourne, Ozzy’s manager and future wife, arranged for a lunch meeting at the label’s New York City offices in May 1981 as a way to introduce the staff to Ozzy and get them behind the project. Sharon had Ozzy bring two white doves to the meeting, which he planned to release as a gesture of goodwill. As the birds flopped around the room, Ozzy introduced himself to the 25 or so CBS executives gathered for the meeting. For a brief moment, Ozzy—a little buzzed from some cognac he’d downed earlier in the day—quit making the rounds and sat on the leg of a girl who worked in the publicity department. As the chords of “Crazy Train” roared in the background, one of the birds landed on the singer’s knee. He picked it up and, without hesitation, put it into his mouth and bit off its head. The CBS suits, horrified at the site of the headless dove’s carcass convulsing on a polished conference table, summarily dismissed Ozzy and Sharon. “We were asked to leave the building,” remembers Sharon, who was herself shocked by the actions of her future husband.

Word of the incident spread quickly. Ozzy Osbourne, depraved rock and roll lunatic, was back in business.

These days, Ozzy Osbourne has it all: a rock-solid marriage, three happy children, mansions on two continents, a clean bill of health and the abiding love and admiration of millions. But his almost bourgeois contentment is only a recent phenomenon. He has spent much of his tumultuous 30-year-career contending with depression, various personal tragedies and a fierce drug and alcohol addiction. He’s been to hell and back, the burn marks clearly visible in his occasionally blank stare, marked stutter and limp.

John Michael Osbourne was born in Birmingham, England, on December 3, 1948, the fourth of John and Lillian Osbourne’s six children. His parents were factory workers, which meant that money, food and clothes, were, particularly for a family of eight, quite scarce. “I had one pair of shoes, one pair of socks—never wore underclothes—one pair of trousers and one jacket,” says Ozzy. “That was it.” Adds Sharon: “All six children slept in the same bed, and they had no bathroom inside the home. He came from nothing.” Lacking the most basic amenities, Ozzy would regularly lose himself in the pounding beat and passion of rock and roll, which helped him imagine a more exciting life beyond his blue-collar hometown. “I loved music as a child, the magic behind rock and roll,” says Osbourne. “My sisters would bring home Chuck Berry records, and I would sing and dance around the house. At night I would lie awake and fantasize about doing something really great.”

Ozzy’s impoverished existence may have been difficult, but the truth is that it was pretty much all he could expect, as he and his family lived a typical Birmingham life. His school days, however, were truly nightmarish. He was often tormented by bullies and, suffering from dyslexia, he consistently scored low grades. One of his regular abusers, an older schoolmate, was a guitarist named Anthony—a.k.a. Tony—Iommi, who would, years later, team up with Ozzy to form Black Sabbath. “I used to hate the sight of him,” recalls Iommi. “I couldn’t stand him, and I used to beat him up whenever I saw him. We just didn’t get on at school. He was a little punk.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Ozzy left school at 15 and bounced from job to job, working for a time at a car-horn factory and in a slaughterhouse. By age 17, however, he was no longer earning an honest day’s pay, having turned to a life of petty crime. Spending a few months in jail—he was caught stealing a television—was enough to make him rethink his career as a larcenist. He emerged from Winson Green prison with the letters “O-Z-Z-Y” tattooed on his knuckles, and a new determination to pursue a career in music.

* * * * *

In 1966, when Ozzy was 18, the Beatles were at the peak of their fame, and no rock and roll band had a more profound influence on him. Swept away by Beatlemania, Ozzy Osbourne knew what he wanted to do with his life. “The whole hysteria around the Beatles just sucked me in. I felt like it was my way out,” says Ozzy. “I wanted to be a Beatle. I used to fantasize about stuff like one of the Beatles marrying my sister.”

Armed with nothing more than his rather nasal singing voice and a small, 50-watt Vox P.A. system purchased on credit by his father, Ozzy set out to form a band by placing an ad in a local music shop window. “In those days,” he recalls, “if you had a P.A. system you were accepted as a singer whether you could sing or not, because nobody could afford the equipment.”

First to respond to the ad was a local guitar player named Terence “Geezer” Butler. He and Ozzy formed a band called Rare Breed that broke up after two gigs. Soon afterward, two other local Birmingham musicians—Tony Iommi, Osbourne’s old schoolyard antagonist, and drummer Bill Ward—saw Ozzy’s advertisement and headed over to his house at 14 Lodge Road.

“It’s pretty amazing, actually,” says Iommi. “Bill and I were looking for a singer, and we spotted this advert that said, ‘Singer looking for a gig. Call Ozzy at…’ I said to Bill, ‘I know an Ozzy. It can’t possibly be that one.’ So we went to the address listed in the ad, and knocked on the door. Sure enough, Ozzy appeared.

“I said to Bill, ‘Forget it, forget it.’ But Bill wanted to chat with him. We talked, but when we left I said, ‘No way, Bill, I know him.’ Three weeks later, we ended up together anyway. Life moves in mysterious ways.”

With Tony handling all guitar duties, Geezer switched to bass by removing two strings from his guitar. Ozzy named the group the Polka Tulk Blues Band, and the foursome began learning blues covers and writing original material. The band quickly changed its name to Earth and hit the local blues clubs in search of gigs. Earth was a competent band, but no better than the countless other English groups then trying to imitate traditional black American blues. It became clear to Osbourne, Iommi and the rest that local music fans were beginning to have enough of being force-fed mediocre blues and wanted something different.

Earth’s response was to turn up the volume to frightening decibel levels and start playing heavier, more distorted riff-based material. The result: when Earth took the stage at a local pub, audiences had no choice but to take notice.

“It used to drive us mad to think that we were up there working so hard, playing our guts out while all these guys were sitting around and chattering,” says drummer Bill Ward. “So we turned up the volume louder and louder until it was impossible for anyone to have a conversation.”

As their sound developed into a more bruising dirge, the band took on a new, more frightful persona that would further distance themselves from the local blues competition. Lyricist Geezer Butler suddenly turned his attention toward darker subjects, like nuclear war and the supernatural, while Iommi and his trusty Gibson SG produced one chilling detuned mudslide after another. It quickly became obvious to the band that a name change was in order.

As they headed into rehearsal one day, they noticed that the movie house across the street was showing the 1935 Boris Karloff horror classic Black Sabbath. “I asked myself,” remembers Ozzy, “Why is there a line of people with money in their hands, paying to get the shit scared out of them? It’s because people get a thrill out of being around evil.”

While it was true that the band had struggled up to this point, in part due to its lack of direction, it was equally clear that changing its name to Black Sabbath amounted to a very shrewd decision. Though most of England’s record companies evinced no interest in releasing Sabbath’s first album— recorded toward the end of 1969, in eight hours, for a mere 1,500 American dollars—the Vertigo label had the foresight to release it (in February 1970) and was soon reaping the benefits as rock fans throughout the world embraced Sabbath as the perfect antidote to Sixties flower power. “The whole hippie thing was still happening around that time,” says Ozzy, “and for us, that was bullshit. We lived in a dreary, polluted, dismal town in Birmingham, and we were angry about it. And that was reflected in our music.”

No doubt due to the music’s demonic nature and unforgiving heaviness, radio wanted no part of Sabbath, and the critics lambasted them at every turn. Yet their debut album sold well, eventually reaching Number 8 on the U.K. chart and Number 23 in America. For the first time in his life, Ozzy was a success, and money started coming in, if at first slowly. With his first royalty check, he gave his mother 50 pounds, then took the rest and bought a pair of shoes and a bottle of cheap cologne, “because I hated the way I smelled.”

* * * * *

As Sabbath grew in popularity, the band’s—particularly Ozzy’s—drinking and drug habits worsened. “We had money to burn and booze coming out of our ears,” says Ozzy.

Later Sabbath albums like Paranoid (1970), Master of Reality (’71), Vol. 4 (’72) and Sabbath Bloody Sabbath (’73) broke the band wide open, earning it international superstar status. But there was a steep price to pay for all the fame: the band members adopted wild lifestyles and rampant substance abuse that began to undermine their creative output. Ozzy remembers the atmosphere surrounding the recording of Vol. 4, an album which, save for a few gems like “Snowblind” and “Supernaut,” is widely regarded as a convoluted mess. “When we did that album it was like one big Roman orgy. We’d be in the Jacuzzi all day doing coke, and every now and again we’d get up to do a song.”

Tony Iommi recalls one particularly heinous incident from around this period. “We were all in an elevator in this really plush hotel, and Ozzy decides to take a crap. As he’s doing it, the elevator is going down to the reception floor. The door opens suddenly—and there’s Ozzy with his pants around his knees. And all these people in fur coats are just staring at him with their mouths open.”

Clearly, Ozzy and Sabbath were riding high, living the wild rock and roll life they had always dreamed of. Unbeknownst to them, all was not right with their financial affairs. Despite selling millions of records, the members of Sabbath realized they were broke, in 1974, thanks to years of mismanagement. Down, but far from out, the band took to managing itself for a while and eventually hired a well-heeled English manager named Don Arden. His introduction to the fold had only a marginal effect on the band’s career, but it did mark a turning point in Ozzy’s personal and professional life. Arden’s 18-year-old daughter, Sharon, worked in his management company as a receptionist, and it was she who would eventually spearhead Ozzy’s solo career and be the rock in his otherwise unstable life.

“He frightened the life out of me,” Sharon says of her first meeting with Ozzy. “He had on a pajama top, no shoes, and was wearing a faucet on a string around his neck. That was his idea of jewelry. But we kept meeting found him to be very sweet and very funny. He was like a little puppy—very vulnerable.”

Ironically, it wasn’t long after Sabbath began working with Don Arden— and Ozzy began falling for his daughter— that the relationship between the band and its frontman began to unravel. As evidenced by the musically disjointed and poor-selling album Technical Ecstasy (1976), Sabbath were losing their focus as a band, a circumstance that more than likely was the product of a lethal combination of the group’s recent mass success, managerial distractions and excessive drug use. As Ozzy grew more distant and disinterested in making music with Sabbath, the band’s frustrations neared the boiling point. “We had totally lost our way by that point,” says Iommi. “And we were all into drugs, not just Ozzy. It was taking longer and longer to make records.”

* * * * *

Ozzy received a crushing blow in 1977 when his father died, sending the singer into a severe state of depression. Unsure of whether he wanted to continue with his career, Ozzy actually quit Black Sabbath for a brief period while the band was writing material for its next album, Never Say Die! He returned two days before recording began but refused to sing any of the material written in his absence. “We ended up having to write in the day so we could record in the evening, and we never had time to review the tracks and make changes,” says Iommi. “As a result, the album sounds very confused.”

Though Ozzy had returned to complete the album and subsequent tour, it was clear to Tony and the rest of Sabbath that the time had come to replace Ozzy. “We knew we had to bring in somebody else,” says Iommi. “Geezer and Bill would say to me, ‘Either Ozzy goes, or we go.’ At that point, Bill was becoming the businessman of the band, with his briefcase and his haircut, and he fucking goes and tells Ozzy, ‘Tony wants to get rid of you.’” He laughs. “Ozzy always thought that I fired him on my own, when it was really the other two who wanted him out. But I wasn’t too pleased with Ozzy, either.”

Ozzy had battled depression on and off for most of his life, but being fired from Sabbath brought him to his all-time lowest point. “I wasn’t just depressed,” remembers Ozzy, “I was suicidal. I stayed in a hotel room in Hollywood for six months and never opened the drapes. I lived like a slob.”

With his body ravaged by excessive drug and alcohol intake, his psyche near the breaking point and his personal wealth all but gone, Ozzy—who was now pretty much alone in the world—desperately needed a savior. He got it one day during the summer of 1979, when Sharon Arden came to his hotel to collect the $500 a mutual friend had given Ozzy to hold. Of course, Ozzy had long since blown the money on booze and drugs, and Sharon was furious. Yet somehow her anger was overshadowed by her fondness for Ozzy and her conviction that he could still revive his sagging career. “I would lecture him like a school teacher about the way he was living,” says Sharon. “I told him he had to pull himself together, and he did.”

“She saved my life,” says Ozzy.

* * * * *

With Sharon’s prodding, Ozzy geared himself up for the next phase of his career: that of a solo artist. For Sharon, still working for her father, Ozzy’s solo venture was the opportunity she had been looking for to strike out on her own as a rock manager. “I never had any doubts about Ozzy going out on his own,” says Sharon. “He just has this natural gift to entertain.”

Rejuvenated, Ozzy began holding auditions in the fall of 1979 in Los Angeles. After hiring former Uriah Heep drummer Lee Kerslake and former Rainbow bassist Bob Daisley, all that remained for Ozzy to find was a guitarist.

Randy Rhoads was a 23-year-old local guitarist who had recorded two albums with L.A. rock outfit Quiet Riot (released only in Japan) and had come to the audition on the recommendation of Dana Strum, a friend of Sharon and Ozzy’s who later became the bassist for the group Slaughter.

“When Randy first walked in, I thought he was a guy in drag,” recalls Sharon. “He was so beautiful and so little.” While these were hardly the physical attributes Ozzy was looking for in a guitarist, Randy walked into Ozzy’s L.A. hotel room, fired up his Charvel guitar and let loose with a blazing fury of classical runs and hard-edged riffing. His physical grace and demonic speed floored Ozzy, who, despite being in a “delicate” condition, almost immediately knew that he had found the last piece of the puzzle. With his band together, it was time for Ozzy to show the world that he could be an even more potent performer on his own than he was during his years with Sabbath.

He had a lot of help. It wasn’t long before Ozzy and Randy became close friends, something Ozzy had lacked during his Sabbath tenure. Their relationship was even stronger when it came to work: feeding off each other’s distinctly different musical sensibilities—Ozzy’s flair for coming up with good hooks, Randy’s disciplined virtuosity—they made a magical duo. “Since Randy was a guitar teacher, he had a lot of patience and would give me the time to come up with ideas,” says Ozzy. “Whereas Black Sabbath would just say, ‘Okay, here’s a riff. Put a vocal line here.’ ”

* * * * *

Though Ozzy was still far from clean and sober at this point, he did have more fire than booze in his belly. With Randy at his side, Ozzy regained his confidence and, in March 1980, recorded his debut solo album. Released in September of that year on Don Arden’s Jet Records label (distributed through CBS), Blizzard of Ozz quickly became a benchmark album for Ozzy. Despite its creepy Sabbath-esque cover image depicting a red-caped, demon-possessed Ozzy wielding a crucifix, Blizzard of Ozz was a markedly different animal from anything by his former band, offering a cleaner and more sophisticated alternative to Sabbath’s trademark sludge. But it did rock in a serious way, proving to be a far tighter and more substantial effort than anything Sabbath had done in years.

Young female metallers who had no use for Sabbath’s monolithic brutality suddenly gravitated toward Ozzy’s melodic, radio-friendly hooks on songs like “Crazy Train” and “I Don’t Know,” while the guitar community embraced Randy’s blistering neoclassical fretwork and gothic pop compositions. Blizzard of Ozz spearheaded a new era in metal and put Ozzy at the top of his game. Ultimately, it sold more than four million copies.

His good fortunes continued the following year with the release of Diary of Madman, also on Jet/CBS Records. For this album, Blizzard drummer Kerslake and bassist Daisley were replaced by Tommy Aldridge, formerly the drummer with Black Oak Arkansas, and Rudy Sarzo, who had played in Quiet Riot with Randy. To some, Diary—with its thunderous opening track, “Over the Mountain,” and the Rhoads showcase “Flying High Again”—was an even stronger album than its predecessor. It posted equally impressive sales figures.

“When we were recording, he would disappear into the studio for days,” Ozzy says of Rhoads. “I’d ask him what he was doing and he would say, ‘I’m working on this solo and I still can’t get it.’ Finally, it would come to him, and he would call me and say, ‘Listen to this!’ It would always tear my head off.”

By this point, Ozzy and Sharon were inseparable, as business partners and lovers, but there remained one enormous impediment to their happiness: Ozzy was still married to Thelma Riley, a local Birmingham girl with whom he had two children, Jessica and Louis. As time wore on, Ozzy and Thelma’s relationship grew strained, no doubt due to Ozzy’s long stretches away from home and his continued substance abuse. “I was taking drugs so much I was a wreck,” recalls Ozzy. “The final straw came when I shot all our cats. We had about 17, and I went crazy and shot them all. My wife found me under the piano in a white suit, a shotgun in one hand and a knife in the other.”

The Diary of Madman tour was a smashing success, but Ozzy’s excesses were nearing dangerous proportions. The heavy metal hero, adored by millions of youngsters, rapidly degenerated into every mother’s nightmare.

* * * * *

It wasn’t uncommon for Ozzy to spend an entire night after a show drinking, which is what he did one night in January 1982, while on a tour stop in San Antonio, Texas. Sharon, in an effort to keep Ozzy confined to the hotel, hid all of his clothes. At 7 a.m., frustrated by his captivity, Ozzy put on one of Sharon’s dresses and a pair of high heels and headed outside. Some time that morning, he stopped to urinate on an old wall. It turned out to be part of the Alamo, site of a legendary 1836 battle between Texans and the Mexican army. Ozzy was promptly arrested and barred from playing in San Antonio for the next decade.

During a concert later that month in Des Moines, Iowa, a fan hurled a dead bat up on stage. Thinking it was a toy, Ozzy picked it up and bit off its head. He was rushed to the hospital after the show as a precaution and had to receive preventative rabies shots for the next few weeks. Diary of a madman, indeed.

For a period of five years, Ozzy’s life had ping-ponged between tragedy and triumph—the death of his father, his firing from Black Sabbath, his resurgence as a heavy metal icon, his ongoing battle with drugs and alcohol, and so on. But it all paled in comparison to the catastrophe that struck on March 19, 1982, the day his best friend and musical inspiration, Randy Rhoads, died in a freak plane crash in Leesburg, Florida. Sharon recalls the events surrounding the incident:

“It was an overnight drive to Orlando, where we were scheduled to play at the Rock Superbowl XIV festival with Foreigner and UFO. We had to go past the home of the bus driver, Andrew Aycock—he lived at this place called the Flying Baron Estates. The buses were kept there, and he needed a couple of spare parts. We pulled into this area, and there was a small landing strip with some small aircraft. There was a big green field, three houses and the airfield.

“Ozzy and I were asleep on the bus. There was also [bassist] Rudy Sarzo, [drummer] Tommy Aldridge, Randy, Ozzy, a tour manager named Jake Duncan, [keyboardist] Don Airey, the bus driver’s ex-wife and Rachel Youngblood, who was a 58-year-old lady who took care of all the band’s clothes and cooked for them. She was a great friend of ours.

“It was about nine in the morning. Don Airey and the bus driver were awake, and they saw the planes. It turns out that the bus driver was also a pilot, even though none of his paperwork was in order. We also learned later on that he had been in a previous crash where a young boy was killed. Anyway, Don asked the driver, who apparently took one of the planes from the compound without permission, to take him up for a ride. So they go up for a while and land. Don then comes back in the bus and wakes everybody else up to go on the plane. Well, nobody else would go except Randy and Rachel. They went up, and the bus driver’s ex-wife was standing outside the bus, watching. And then, before you knew it, the plane came down and went right through the bus and into one of the houses.

“Ozzy and I woke up, the back of the bus crushed down on us, and we had no idea what was happening. I ran to a nearby house to call for help, and it turned out that the owner of the house was also the owner of the plane. He and his wife just sat there, not offering to help and refusing to believe that a house across the way was on fire.

“It was just a horrible scene: The house was on fire, airplane pieces were scattered all around, the bus was destroyed and there was blood and bodies everywhere. There was nothing left—the pilot died, Rachel died, and Randy died. Instantly.

“The whole thing will always be a mystery to us. Randy was terrified of flying! What would make him go up there? Ozzy and I will wonder about it until the day we die. In my opinion, there was more going on. In the autopsy report, they found cocaine in the bus driver’s system, a considerable amount, and of course he had been fighting with his ex-wife. I think for that one instant, while flying, he looked down at his ex-wife and said ‘forget this,’ and tried to kill her. Why Randy and Rachel—who, incidentally, didn’t even like each other—had to be on that plane, though. It was just a horrific day.”

Though Ozzy prefers to not discuss the bizarre circumstances surrounding Rhoads’ death, he is quick to acknowledge Randy’s brief but undeniable impact on the rock guitar community: “He was an exceptional musician, a dedicated guitarist, and he was always fun to be around,” says Ozzy. “He could be so shy, but then people would hear him play and he’d blow them off the face of the earth. If he were still here with us, he’d be at the forefront of what guitarists were doing. He’d be the leader. Not a day goes by that I don’t think about him.”

Though clearly devastated and uncertain of his future as a solo artist, Ozzy made immediate plans to return to the road. For one thing, he needed the money that a lengthy summer tour would generate (“After selling 5.5 million copies of the first album, Ozzy only received $15,000 in royalties,” says Sharon, referring to Ozzy’s unfavorable contract with her father’s record label). For another, it was a form of instant therapy to help him cope with Randy’s death. “Getting back on point,” says Sharon. “If we had stayed home and done nothing, the band would have fallen apart. I never would have been able to get Ozzy back onstage again.”

Says Ozzy, “When Randy got killed, I said to Sharon, ‘I can’t keep doing this.’ And she said, ‘Yes you can. If Randy was alive, this is what he would want you to do.’ So I decided the best thing to do would be to get back out on the road. And it wasn’t the most amazing show, but we did it.”

* * * * *

Finding a suitable replacement for Rhoads was not an easy task for Ozzy. First to be approached was ex–Thin Lizzy guitarist Gary Moore, who was also managed by Sharon, but he declined. Michael Schenker volunteered, but his asking price was too high, especially in view of Ozzy’s financial troubles. Then, as singer Ian Gillan disbanded his own outfit, Gillan, to join Black Sabbath, Gillan’s guitarist, Bernie Tormé, was tapped by Ozzy to replace Randy on the tour. But Tormé, a disciple of the Hendrix school of blues-based rock guitar, was clearly not the right man to fill Rhoads’ stylistic shoes. “Bernie was okay, but Randy wasn’t dead a month, and it’s a hard thing for any guitarist to be in that position,” says Ozzy. “I wouldn’t have done it.” After a few weeks, Tormé told Ozzy he was planning to leave the tour, and Ozzy found himself once again in search of a new guitarist.

Longtime Night Ranger guitarist Brad Gillis tells how he, at the time a 24-year-old Californian, was suddenly thrust into the spotlight as Randy’s second replacement. “I was with the band Ranger before we were Night Ranger, and we were looking for a record deal. But we weren’t doing very many gigs, so just to keep busy I put together another rock band called the Alameda All Stars. We played around California, and during the shows we would do two Ozzy songs, ‘Flying High Again’ and ‘Mr. Crowley.’ About two weeks after Randy died, a friend of mine who also knew [Ozzy’s drummer] Tommy Aldridge told Tommy about me, and Tommy told Sharon and Ozzy. Next thing I know, I get a call from Sharon asking me to fly out to New York for an audition. I had about two days to learn the entire set list. I thought it was going to be a rigorous audition process, but when I got there, it was just me.”

For the next five days, Gillis traveled with the band, watching the shows, learning the set and practicing for 10 hours a day. Finally, with Tormé about to leave, Ozzy asked Gillis if he was ready. Their first show together was in Binghamton, New York, “one of the scariest nights of my life,” says Gillis. “I pretty much pulled off every song that night except ‘Revelation (Mother Earth),’ which starts off slow, then picks up speed somewhere in the middle— and I came in one verse too early. Ozzy looked over at me after realizing that I was in the wrong section, and I quickly had to recover and find my place. After that show, everyone congratulated me for doing a good job, and Ozzy came over to me and said, ‘We won’t screw up on “Revelation” anymore, will we?’ And I said, ‘No we won’t!’

“But it was tough in the beginning for me. A lot of the fans out there were holding up ‘Randy Lives!’ signs and giving me the finger and stuff. But they came around eventually.”

* * * * *

In July 1982, Ozzy and Sharon were married in Maui, Hawaii. Gillis recalls the celebration: “That was a trip. They had a little Hawaiian band playing at the reception: a couple of acoustic guitars and a two-piece drum kit. And we got up and did ‘Paranoid’ on acoustic guitars, with Rudy Sarzo playing an upright bass and Ozzy singing in his little wedding outfit!”

With his new marriage, the successful continuation of the tour despite Randy’s death and both Blizzard of Ozz and Diary of Madman climbing back up the charts, things were clearly going well for Ozzy. Yet, despite all the good fortune in his life, Ozzy’s drinking and drug abuse had once again spun out of control.

“I remember we had to cancel a show in Bakersfield, California, because Ozzy pretty much couldn’t play the gig,” Gillis recalls. “We told the audience that he had food poisoning and that we’d taken him to the hospital, but really he was just passed out in the back of the bus. He was drinking a lot in those days and dabbling in other things, and we helped him out as much as we could by being supportive. And things were going good for him. All the shows were sold out and the records were selling, but he was still depressed over Randy’s death. He needed real help to pull him through this.”

Around this time, Sharon and Ozzy were desperately trying to break free from the financially constricting contract Ozzy had with her father and Jet Records. “My father used to take 90 percent and give the artist only 10 percent,” says Sharon. But Arden wouldn’t budge, aware that letting Ozzy go would mean losing millions of dollars in potential income. A vicious legal battle between Sharon and her father ensued, and while the two had not exactly seen eye-toeye since her departure from his company a few years earlier, this power struggle led to the final break in their relationship—professionally and personally. Eventually, after paying Don Arden $1.5 million for Ozzy’s contract and delivering one last album to fulfill the artist’s contractual obligations to Jet Records—1982’s live Speak of the Devil, which featured only Black Sabbath songs recorded on the current tour—Ozzy and Sharon’s dealings with her father and his company were over. While this was considered a victory within the Osbourne camp, it’s clear that certain scars still have not healed. Asked if her father is still alive today, Sharon’s icy response is, “Yes he is, unfortunately.”

Not long after the release of Speak of the Devil, with the successful world tour winding to a close, Gillis felt that the time had come to leave Ozzy’s band and return home to pursue a career with his own band.

“When Night Ranger finally got a record deal, I had to make a choice,” he recalls. “I had spent many years with those guys, and I was more comfortable in a band situation than being a sideman. So I told Ozzy, and he was cool about it.”

“I’m forever indebted to Brad because he put his own project on hold so he could come out and help me on the tour,” says Ozzy. “And when he was ready to leave, I said, ‘You should go with your heart, Brad, because you don’t owe me a thing. If anything, I owe you.’ ”

* * * * *

For the fourth time in little over three years, Ozzy was in need of a new guitarist. Again, he enlisted the help of Dana Strum, the man responsible for introducing Ozzy to Randy. Strum handpicked 25 guitarists from around the L.A. area and sent tapes, pictures and bios of each to Ozzy. One of the candidates was 24-year-old Jake E. Lee, who’d been sitting idle since leaving his band, Rough Cutt, three months earlier.

“George Lynch [of Dokken] actually got the gig before I did,” recalls Lee. “He went on the road with Ozzy’s band for about two weeks to watch and learn the material. I figured that George had it, but then Dana called me and said that Ozzy wanted to audition me and Mitch with the band. So a few days later, we went to S.I.R. Studios in New York for the audition. Mitch went first, I went second, and after I played Ozzy came up to me and said, ‘If you want it, you got it.’ Then George walked in, and Ozzy turned to him and said, ‘You’ve lost the gig. It’s his,’ and walked away. I’ve seen Ozzy fire a couple of people, and it’s never pleasant.”

Though they would work together for only a few years and eventually part under not-soamicable circumstances, it was clear that Ozzy Jake E. Lee. Their first album together, 1983’s Bark at the Moon, showcased Lee’s fiery shred ability and penchant for wah-wah-saturated leads and razor-sharp metallic riffing, making him the ideal successor to Randy Rhoads and an important figure in the evolution of Eighties rock guitar. His flashy showmanship both as a player and performer radiated a confidence that quickly endeared him to Ozzy’s fan base—though Ozzy himself was hardly tickled by Jake’s cocksure attitude.

As one might expect, Jake, too, has less-thanfavorable recollections of his time working with Ozzy: “He was fucked-up and drunk most of the time—pretty much for the whole four years I was with him. He would guzzle whole bottles of cognac—I never saw anyone drink like him. It created a lot of communication problems between Ozzy and the rest of the band. There were plenty of nights where he’d knock on my hotel door at three o’clock in the morning, get me out the tape recorder, and he’d start trying to tell me about this idea he had for a song, but it would be all mumbling and incoherent. And he’d get really pissed off at me because I couldn’t understand what he wanted me to do.”

Ozzy’s drug and alcohol consumption were at an all-time high during his years with Jake E. Lee, sending his health into decline and his weight into the stratosphere. (He ultimately reached 220 pounds, which, he says, was “all from beer.”) In the liner notes to his 1986 album, The Ultimate Sin, Ozzy thanked “all friends at the Betty Ford Centre.”

“There was one show that I’ll always remember,” says Jake. “It was at some outdoor festival somewhere, and Ozzy and Sharon had gotten into a big argument before the show, and she took off with the kids on the tour bus. Ozzy drank so much that day that he was totally fucked up by showtime. He put on one of Sharon’s dresses, some high heels and a big, flowery sun bonnet and put on some lipstick. We started the first song, and halfway through Ozzy just quit singing. Then he started telling the audience about how he and Sharon had had a fight, and that she had left him, and what was he going to do? The tour manager was off to the side of the stage, yelling at me to start the next song, so I did. And Ozzy got real pissed. He made me stop playing, and then he started telling the story again. A couple of the road crew guys came out and took Ozzy off the stage, and the band left, too. I don’t think the crowd was too pleased about it.”

* * * * *

On March 19, 1987—exactly five years after Randy Rhoads’ death—Ozzy released the Tribute album, a collection of never-before- heard live music (from a 1981 Canadian performance) featuring the late guitarist. “After Randy’s death, I just wanted to hold on to the material,” remembers Ozzy. “It was locked away in a vault. I didn’t want to hear it, I didn’t want to even know about it. When we found the recording years later and listened to it, it only took about a minute and we were devastated. It was that good. Any initial fears or worries we had about putting the record out were put to rest that fast. People just had to hear it, hear Randy play. That’s all I could think. This is actually the only official recording of us live with Randy. That’s why it’s special.”

Soon after the release of the Tribute album, Jake E. Lee was relieved of his position in Ozzy’s band. (“Ozzy started telling people that I didn’t want the Tribute album to come out, but that was never true,” says Jake. “I think it was just his way of trying to justify firing me, because there really didn’t seem to be a reason.”) Ozzy was in need of a guitarist yet again. Only a few months would pass before he would make yet another discovery, this time a 19-year-old unknown from New Jersey: Zakk Wylde.

With his bell bottoms, Confederate-flag guitar and screeching shit-kicker licks, Wylde was a fresh face on the guitar scene, a grungy, unbridled combination of Rhoads’ skill and Lee’s flashiness, yet clearly his own player. Though Zakk ceased being an official member of Ozzy’s band in 1995 (“He was negotiating with Guns N’ Roses, had his Pride and Glory project going and said he wanted to tour with me,” says Ozzy. “He obviously didn’t know what he wanted to do, so I made up his mind for him.”), his trademark squeaks and squeals and churning metal riffs grace the last three Osbourne studio albums, No Rest for the Wicked (1988), No More Tears (1991) and Ozzmosis (1995). Today, Ozzy is taking a wait-and-see approach as to which musicians he selects for touring and recording. “I’m at a point in my life now where I don’t have to have a permanent band,” says Ozzy. “The beauty of being Ozzy is that it doesn’t matter who I get up there with, as long as I get up there.”

* * * * *

It’s been 30 years since Ozzy first picked up a mic with Black Sabbath, a dizzying career in which he has frequently scaled the heights of heavy metal stardom—and hit rock bottom just as often. “I haven’t sat on my ass all these years picking up royalty checks off a conveyor belt,” says Ozzy. “I’ve worked damn hard to get where I am.” Today, he has few battles left to fight. Drug-free since 1991, Ozzy continues to lead a healthy lifestyle that includes an intense daily workout regimen (his weight is back to its normal 165 pounds). He even recently triumphed over one of his last remaining vices: nicotine. “I’ve done all kinds of drugs, but cigarettes are one of the most addictive things I’ve ever put into my body.”

His annual Ozzfest tour continues to be one of the highest-grossing summer packages, knocking Lollapalooza from its perch as the festival du jour. Ozzy is currently putting the finishing touches on a new project with a reunited Black Sabbath: a live recording of two shows the band played last December in its hometown of Birmingham, England. The album, set for release this fall, will also feature two new studio tracks, a possible sign that a full Black Sabbath reunion album is on the way. “It’s so nice,” says Ozzy, “especially after all the hostility, the anger and the bad things we’ve said about each other over the years, to come full circle and be friends again.”

His career is on track, his financial status and family life are secure, his health is no longer in question and he’s even reconciled with his former sparring partners in Sabbath. Clearly, the madman side of Ozzy Osbourne has been laid to rest, along with a few headless winged creatures and a houseful of shotgunned cats. He’s survived all his battles and come out on top, at ease with the many misfortunes it’s been his misfortune to endure…well, almost.

“I have no real regrets,” says Ozzy, “except that I wasn’t up to keeping Randy Rhoads from getting on that plane. I’m no superman, no person from another planet. I’m just a lucky guy.”

“The Strat was about as ‘out’ as you could get. If you didn’t have a Floyd Rose, it was like, ‘what are you doing?’”: In the eye of the Superstrat hurricane, Yngwie Malmsteen held true to the original

“He got that from me. I used to throw my guitar as high as I could, like, 20 feet, and my guitar tech would catch it”: Dez Dickerson on Prince, his iconic Little Red Corvette solo, and why he left the Revolution