Ozzy Osbourne: Crazy Train

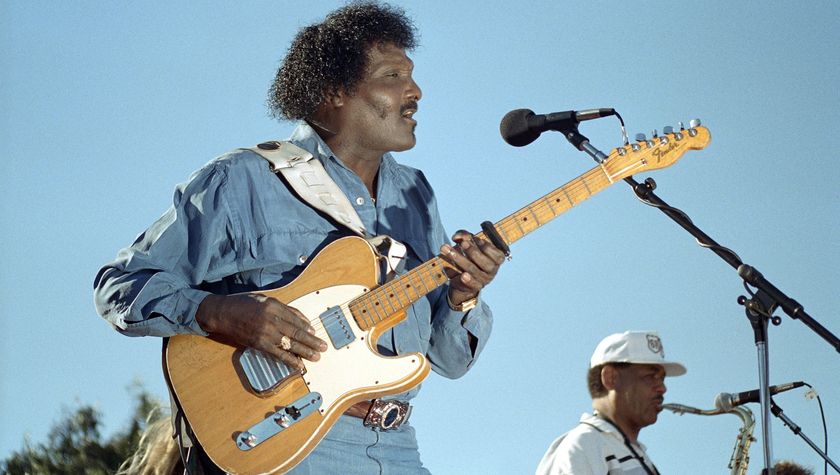

His rise was meteoric— swift, brilliant and all-too brief. In March 2002, on the 20th anniversary of his death, Guitar World paid tribute to Randy Rhoads, the ground- breaking guitarist who helped Ozzy Osbourne get his career on track.

“There are some people who are like a shooting star. They come and hit the planet and explode into a beautiful rainbow of colors. Then they shoot off somewhere else. And that was the life of Randy Rhoads.”

Ozzy Osbourne waxes uncharacteristically poetic on the subject of Randy Rhoads. The legendary guitarist was just 25 years old when he died in an airplane accident on March 19, 1982, while on tour with Ozzy’s band. These days, Osbourne is a metal icon; as figurehead for the annual Ozzfest he’s become a tattooed patriarch for a whole new generation of hard-music fans, but things were very different when the singer first met up with Rhoads in 1979. Ozzy had just been fired from his original band, Black Sabbath. For all intents and purposes, he was holding a one-way ticket to Palookaville.

“I was a drunken, drugged-out, fucked-up slob,” Osbourne admits. “But Randy was patient with me.”

Rhoads’ composure benefited them both. Osbourne’s solo career was launched by means of the two albums he recorded with Rhoads, 1980’s Blizzard of Ozz and ’81’s Diary of a Madman, and those records form the basis for Rhoads’ own formidable legend. More significantly, his stunning guitar technique, classical influences and admirable musical discipline on those albums helped launch the Eighties shred boom.

But Rhoads’ appeal has long outlived the era of big hair and spandex leotards. While he doesn’t have the status of dead rock stars like Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison or John Lennon, Rhoads nonetheless holds a special place in the rock guitar subculture. He is the all-American guitar hero, the golden-haired patron saint of every kid who ever labored long and hard to master metal licks in a suburban bedroom.

Rhoads was born December 6, 1956, in Santa Monica, California, and raised in the L.A. suburb of Burbank, which for many years was an enclave of conservatism and traditional family values amid the bizarre cultural circus that is greater Los Angeles. Rhoads’ earliest musical instruction was given to him by his mother, Delores, a professional musician who ran a music school in Burbank and raised her three kids single-handedly.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

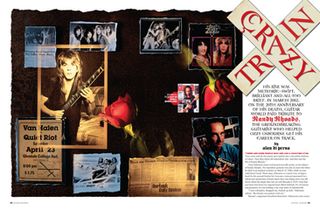

By the time he was in his teens, Rhoads was teaching guitar at his mom’s music school. He taught his junior high school friend Kelly Garni how to play bass, and together they worked their way through the usual assortment of garage bands, ultimately forming Quiet Riot with drummer Drew Forsyth and singer Kevin DuBrow. By the mid Seventies, Quiet Riot became the house band at the Starwood, Hollywood’s archetypal rock dive. The Sunset Strip glam-metal scene was in its formative stages back then.

“The real hardcore music was going on at the Starwood,” Garni recalls. “You had Van Halen down the street at Gazzarri’s. They were doing a Top 40 thing.”

Eddie Van Halen and Randy Rhoads were the two prime originators of the pyrotechnic guitar style that would come to dominate Eighties metal. Both brought a new level of technical expertise to rock guitar playing. But while Eddie’s approach was intuitive and rooted in traditional rock aesthetics, Randy’s arose from a classical foundation he acquired through his formal musical training. For the most part, he broke with rock’s long tradition of spontaneously improvised solos, a custom that stemmed from African-American musical forms like jazz and blues. Instead, Rhoads brought the rock guitar solo closer to the spirit of the classical cadenza—a set piece specifically designed to showcase technical virtuosity.

Rhoads frequently shunned blues-based, African-American– derived pentatonics in favor of classical scales and modes, such as the natural minor (Aeolian) intervals heard in his solos for Ozzy’s “Crazy Train” and “Believer.” Rhoads was not the first axman to use these modes; earlier metal guitarists like Deep Purple’s Ritchie Blackmore had also favored minor scales. What sets Rhoads’ use of these modalities apart is the level of articulation he was able to bring to even the most difficult passages. His fluid legato feel was unique in all the world of rock.

Progressive rock bands such as Yes, Gentle Giant, Focus and Emerson, Lake and Palmer had also previously popularized the use of European classical modes and virtuosity in rock music. But Rhoads’ appropriation of these elements is completely devoid of prog-rock’s “high-brow,” Euro leanings. Instead, while astoundingly precise and harmonically astute, his playing is unmistakably Caucasian American—and 100 percent heavy metal. His biggest heroes, after all, were people like Leslie West and Alice Cooper guitarist Glen Buxton, not Beethoven and Mozart.

In terms of his instrument and stage look, Rhoads took a major cue from the transgendered glam-icon image of David Bowie guitarist Mick Ronson and even began playing a white Les Paul, as Ronson did. Rhoads’ stage outfits were designed by his longtime girlfriend Jody Raskin. They featured huge polka dots, which later became something of a Rhoads trademark, and big bow ties, generally worn over a bare torso. While DuBrow was Quiet Riot’s extrovert onstage and off, it was Rhoads who “unquestionably stole the show,” according to Garni.

“He was five feet seven inches, and he weighed only 105 pounds,” says Garni. “His guitar was almost bigger than him. But he’d run around like a wild man with it and just be humongously loud. As shy as he was, Randy was the star.”

The band recorded two albums, Quiet Riot I and Quiet Riot II, but was unable to secure U.S. releases for either disc; both records originally came out in Japan only. (Highlights from the albums were posthumously reissued in 1994 on the CD Quiet Riot: The Randy Rhoads Years.) Disillusioned with the band’s inability to get any farther than Sunset Strip, Garni left in 1979, shortly after the recording of Quiet Riot II. He was replaced by Rudy Sarzo. The Cuban-born bassist, a former hairdresser, became Rhoads’ new friend and took charge of his coiffure. The two would also go clothes shopping together. “The funniest thing,” recalls Sarzo, “is that because Randy was so little—like, a size one—we used to go to girls’ stores for his jeans and stuff like that. He couldn’t find the right size in a men’s store.”

Despite his newfound friendship with Sarzo, Rhoads exited Quiet Riot a few months after Garni. “We were doing everything possible to get ourselves an American record deal,” says Kevin DuBrow, “but the band was going nowhere fast, and Randy knew it. In October 1979, Randy—unbeknownst to me—heard that Ozzy Osbourne was auditioning guitar players, so he took his little practice amp and tried out.”

Osbourne takes up the tale. “Even though I was fucked up on cocaine and booze, I remember when I first met Randy Rhoads. I was staying at a hotel called Le Parc on West Knoll off Santa Monica Boulevard [in West Hollywood]. I used to live like an animal then. And Dana Strum from Slaughter says to me, ‘I’ve got this fucking amazing guitar player for you.’ And I go, ‘Yeah, sure.’ ’Cause at the time, everybody was a fucking Hendrix clone. So it was one in the morning and I was fucking smashed. Off the wall. And this little guy comes in. I thought he was gay at first. He was very effeminate looking, and he wore little boots. He looked like a fucking doll. But even in my stupor, I realized he was great as soon as he started playing the guitar.”

By this time, Ozzy had been ejected from Black Sabbath in a manner less than friendly. His excessive drinking and drug use had estranged him from his first wife, Thelma Riley. His management had been undertaken by Sharon Arden, daughter of former Sabbath manager Don Arden. Sharon and Ozzy’s business relationship grew into a love affair, a frequently explosive romance that, nonetheless, would eventually result in marriage. Along with Rhoads, they recruited two British rock vets: former Rainbow bassist Bob Daisley and ex–Uriah Heep drummer Lee Kerslake. This would be the group to launch Ozzy’s solo career.

Singer, manager and band decamped for England, where they began preparations for Ozzy’s solo debut album. Despite differences in age, nationality, personal discipline, professional experience and capacity for alcohol and drug consumption, Ozzy and Rhoads soon became fast friends. “Sharon, Randy and I and a couple of roadies, we’d go out and be goofy,” Ozzy recalls. “We loved that. I remember Randy liked to drink Kahlúa and milk. We’d get drunk and start fights. And Randy was a hundred and fucking five pounds wet, you know.”

Rhoads’ legend tends to paint the guitarist as something of a choirboy, an innocent adrift in the decadent world of rock and roll. But the human being behind the legend wasn’t quite so angelic. “Randy’s consumption of drink was nowhere near Ozzy’s,” says Sharon. “But when Randy did drink, he had a wicked little sense of humor. He would love to wind people up. Like we were once in a hotel bar somewhere. Randy went and pissed in his drink, then he gave it to the waitress and said, ‘You know, this scotch doesn’t taste right. You wanna taste it?’ And she was tasting it and, like, dying.”

Women in particular seemed to be Rhoads’ chosen prey when it came to practical jokes. “He used to fuck around with girls—not sexually, but mentally,” says Sharon. “He used to like to play games with them. He was a gorgeous-looking guy, but he was terrible with women! He would really make fun of them.”

Perhaps it was a defense mechanism, or a way of venting frustration as he struggled to remain faithful to Jody, his girlfriend back home, amid the temptations of his new surroundings.

“Jody was Randy’s real girlfriend,” said Ozzy. “But he’d go out on dates. Whether it was physical or not, I don’t know.”

For a while Ozzy and Rhoads shared an apartment in Kensington, one of London’s tonier neighborhoods. By all accounts the household was like a heavy metal reenactment of The Odd Couple, with Rhoads playing Felix Unger to Ozzy’s Oscar Madison. “I was always fucked-up stoned and drunk, like a big, bloated, beer-drinking pig on the floor,” Ozzy recalls. “And Randy used to clean the pots and pans, clear away the empty beer bottles and fuck knows what else.”

Shortly afterward, Ozzy, Sharon and Randy took up residence together in the nearby, but more working-class, London environs of Shepherd’s Bush. “Above the Townhouse recording studios they had apartments that they rented,” Sharon recalls. “We all lived together there. And it was just fucking mad. Shepherd’s Bush is a very Irish area, and on every corner is a pub. On a Sunday in England, the pubs would close at three o’clock, and the streets would be full of drunken Irishmen. So the three of us would make this ‘special mixture’ and throw it out of the window on all the Irishmen walking down the street. The guys used to piss in a great big bowl. We used to put soup in it, and stale old food. There was crap in it; we used to shit in it. Then we’d warm it up on the stove until it smelled. And then as people would walk past, we’d pour it on them. It was funny for a while, but eventually it became a big-time problem. Irishmen would gang up and wait on the corner for us!”

Somewhere amid the boozing and excremental pranks, the band buckled down to write and rehearse material for Ozzy’s solo debut album. “It was a writing team,” says Ozzy. “Randy wrote the riffs, Bob Daisley wrote the lyrics and I came up with the vocal melodies.” The material that became the Blizzard of Ozz album marked a move away from the sludgy sound and satanic overtones of Black Sabbath. The album is relatively devoid of demonic imagery, apart from the goat horns and skull in the sleeve art and a song about British occult author Aleister Crowley. Tracks like the classic rock radio staple “Crazy Train” seem to owe more to the pop metal style Rhoads cultivated back when Quiet Riot were vying with Van Halen for control of the Sunset Strip. Rhoads turned out to be an ideal musical partner for Ozzy. While Ozzy possessed the veteran rock perspective Rhoads lacked, Rhoads had the discipline Ozzy had never cultivated.

“I remember when we started to work on ‘Goodbye to Romance,’ ” says Ozzy. “Randy said, ‘Maybe if you tried it in this key…’ He worked with me. He had the patience because he was a guitar teacher. And he gave me a lot of confidence. He wouldn’t intimidate me. Because, believe it or not, I’m quite easily intimidated.”

Once writing for the album was completed, Ozzy, Sharon and the band repaired to Ridge Farm, a residential recording studio in rural Sussex. Ozzy was still without a record deal; the sessions were financed from his own private funds, so the project was on a tight budget. The sessions were initially engineered by Chris Tsangarides, who’d helmed the console on Judas Priest’s Sad Wings of Destiny. But the band was reportedly dissatisfied with the initial sonic results, and Max Norman, who would later produce Megadeth and Grim Reaper, took over as engineer.

“The sessions went pretty fast,” Norman recalls. “Everyone played together, and the stuff was already written, except for the vocals and guitar solos.” Norman reports that Rhoads would always record scratch guitar solos as part of the basic track. “Randy would recut the main solo as an overdub, and then he’d recut the [outro] solo as well. And Ozzy would tell me, ‘No, turn that off and put on the original one.’ And then Randy would go, ‘Oh, all right, but at least let me double it.’ So he’d get in there and double or triple it, and whip some other stuff on there as well.”

According to Norman, Rhoads mainly used a polka-dot Gibson Flying V and his white Gibson Les Paul for the sessions. These were played through a 100-watt Marshall head with two cabinets. “Randy had read somewhere about using the Variac [variable voltage regulator],” says Norman. “So we dragged it in and dropped the Marshall down to 90 or 92 volts. You get a creamier edge to the distortion that way.”

Rhoads’ cabinets were pointed at a flight of stone steps leading up from the basement area at Ridge Farm and close-miked using two Shure SM57s per cab. In addition, a Neumann U87 mic was placed six to eight feet from the cabinet and a second U87 was situated 12 feet to 20 feet away to pick up room ambience. His effects consisted of a pedal board containing some MXR effects and a Vox wah. Norman treated the guitar with control-room effects as well. “The main thing we had in the studio back then was the AMS 1580 digital delay, which was the first good, long digital delay,” he says. “It went to 408 milliseconds, which was a big deal in those days. A lot of the echoes on Randy’s guitar on that album are 408 milliseconds.”

The actual recording of guitar solos was a lengthy process, according to Norman. “Randy would say, ‘I’m going to need to listen to this a lot of times. You can just go to the pub for a couple of hours.’ I’d make him a 1/4 stereo mix of the backing track: I’d record maybe 15 or 20 passes of the section where he’d be soloing, starting about 15 seconds before the solo and ending about 20 seconds after. I’d play that back and send it through Randy’s headphones or through the two big 15-inch Tannoys that we had out on the studio floor. Randy would stand at the top of the steps [leading to the basement where the amps were] and try out ideas for solos. I’d go to the pub for a couple of hours. And when I got back, he usually still wasn’t ready. But once he knew what to do, he’d slam down a good one, and then we’d get it doubled and tripled up.”

The Blizzard album also contains Rhoads’ solo acoustic composition “Dee.” The title comes from a nickname for his mother, Delores. “Randy absolutely adored his mother,” says Ozzy. “And one day Randy came to me and said, ‘Do you mind if I do this classical guitar piece for my mum?’ And I said, ‘Fuck, what yer askin’ me for? Go ahead.’ ”

Max Norman remembers Rhoads as a confident, focused studio musician. “I think everybody was in awe of his composing. His chord changes were great. He was the sort of guy you didn’t argue with; you just tried to keep up. At some point, Ozzy would say, ‘This is taking forever. We don’t need all these tracks.’ Remember, the first album was being done on Ozzy’s money and it was all the money he had in the world, I think, for four weeks in the studio. So we didn’t have a lot of time to hang around trying different ideas. But if Randy really wanted to do something, he could usually bring Ozzy around.”

Actually, quite a bit of time was spent “pulling vocals out of Ozzy,” as Norman phrases it. “It would take about six or seven hours. And it was always a question of getting it out of him before he collapsed, because he’d be drinking scotch or doing blow. One time, toward the end of those sessions, I was recording Ozzy and I couldn’t hear anything. I soloed out the track and I could hear this dribbling sound. And it was Ozzy pissing on the studio carpet. He didn’t even bother to sing. Another time I listened in and he was throwing up.”

Like everyone else, Norman remembers Randy’s consumption of intoxicants as being very moderate. “He’d never take a drink in the studio. Maybe after the session, but that was it. One of his little fingers had a very long fingernail on it, and maybe he’d have a tiny bit of cocaine on there, maybe at the end of the week. He was a very straight guy; he was into playing. I saw him do coke maybe three times I can think of. And in those days, that was like being a Christian. Everybody else was crazy.”

Shortly after Blizzard of Ozz was completed, Ozzy signed a deal with Don Arden’s CBS-distributed Jet Records, and the band started to tour behind the album’s September 1980 release. At first, the going wasn’t easy. The general perception was that Ozzy’s best days were behind him and that he’d become just another booze-and-dope casualty. And at the dawn of the Eighties, heavy metal was far less popular than it is today. Seventies metal, the music’s first wave, had long since peaked. A significant portion of the rock audience had moved on to newer styles such as punk, post-punk, hardcore, industrial, Two-Tone ska, new wave, no wave, synth pop and the rockabilly revival, among other genres. Ozzy Osbourne and his new band had to scramble to gain a toehold.

“We had nothing in the beginning,” says Sharon. “We weren’t earning a lot of money from the dates, and it was really, really rough. When we were first starting out, the hotels we stayed in were shit holes. I mean, Motel 6 was a luxury for us. And the first thing Randy would do when he got into one of those rooms was jump up and down on the bed and put the light under the fire alarm. We wrecked a few hotel rooms together.”

According to Sharon, however, Rhoads was not discouraged by the spartan touring conditions. “Randy wasn’t a limo kind of guy. That wasn’t his thing. All he wanted was to play.”

The band’s bassist and drummer, apparently, were somewhat less tractable. “Bob Daisley and Lee Kerslake did nothing but complain from day one,” says Ozzy. “I remember one occasion where Sharon comes to us and says, ‘Good news, guys: our show at the New York Palladium sold out in half an hour and they want to add another show.’ So Daisley and fucking Kerslake go and have a little chinwag, and they come back and say, ‘Okay, we’ll do the second show if we can have double per diem.’ Randy looked at me and said, ‘What the fuck are they on about?’ He didn’t even know what per diem meant.”

Rhoads, of course, was considerably less seasoned than Daisley and Kerslake. To be seeing the world while touring with Ozzy Osbourne was plenty for him. “Every country we went to, Randy would love it,” says Sharon. “He was a real little tourist. When we got to a town, he’d find out what the local tourist attraction was and go visit it. He loved to collect model trains, so he’d go find some local toyshop that specialized in that. You would never have Randy stuck in the hotel room. He’d be out exploring. I mean, he did find the food in Europe a bit difficult. He loved his American food. But he ate a lot of McDonald’s and candy, so it was fine.”

In a sense Ozzy and Sharon became surrogate, if somewhat dysfunctional, parents for Rhoads in his strange new surroundings. “I remember, we were somewhere on the road and Randy had a toothache,” Ozzy recounts. “The problem was a wisdom tooth. Have you ever had a wisdom tooth pulled? It’s like having your fuckin’ head ripped off. So Randy goes to this dentist that rips his face out. By the time we got him back to the hotel, there was about six big Kleenex boxes soaked in blood. And I go, ‘What the fuck have they done to him, Sharon?’ And Sharon’s going crazy, like a mom.”

The band’s hard work paid off and Blizzard of Ozz became a substantial success, with two singles—“Crazy Train” and “Mr. Crowley”—making the charts. Eager to capitalize on their good fortune, Osbourne, Rhoads, Daisley and Kerslake returned to Ridge Farm studios to cut a follow-up to Blizzard of Ozz, with Max Norman once again at the controls. Pleased with the way Blizzard turned out, they went about things much the same way, even down to the placement and miking of Randy’s amp.

“The main difference was that Randy wanted to be in the control room when we recorded the second album,” Norman recalls. “So we set him up using D.I.s [direct injection]. What we ended up doing was preamping the guitar through the board, which was cool because we could actually change the amount of drive into the front end of the amp without killing it. This was before people started making separate preamps and power amps for guitar.”

While preamping the signal to the board, Norman also took the opportunity to add a wider variety of control room effects to the signal. This was partially because more gear had become available since the making of Blizzard. “On the second album, we had a Lexicon 240 [reverb unit] with new chips in it. We used it for some of the spacey clean-guitar stuff. The Lexicon had a long, 30-second delay, and we doubled those guitar figures into it. That made them sound kind of spooky.”

The guitar sounds are generally bigger and warmer on Diary of a Madman, the second Ozzy Osbourne album. Octave-divider and envelop filter–style effects from an Eventide Harmonizer and AMS Flanger impart a sense of depth. In addition, Randy played a wider range of guitars on the album than he had on Blizzard. In the time since making the first album, he’d supplemented his Gibson Les Paul and Flying V with several custom-made V-shaped Jacksons. Compared with Blizzard, the music on Diary of a Madman has more of the stagey, dark melodrama one might reasonably expect from Ozzy Osbourne. The guitar tones have more depth, and much of the soloing possesses a kind of hellbent urgency.

“I remember Randy wasn’t really happy with the guitar solo on ‘Diary of a Madman,’ ” Ozzy recalls. “I said, ‘You know what, Randy? The studio is yours. You can spend as much time on that solo as you want. It’s my record deal, and as far as I’m concerned, you can stay a fuckin’ month in there.’ I remember him coming out of the studio a few days later with this big shit-eating grin on his face. And when I heard the solo, it blew my fuckin’ mind, man.”

But all was not well in the Osbourne camp. Toward the end of the sessions for Diary of a Madman, Ozzy and Sharon fell into a dispute with Bob Daisley and Lee Kerslake. “There was a bit of contention about the publishing,” Norman says. “I remember Daisley and Lee getting pretty pissed off about it at the end. I remember Ozzy talking to Sharon and saying, ‘They’re fucking gone.’ And Ozzy fired them, basically. Ozzy fires everybody. He’s fired me more than once!”

The dispute has never really been settled. Daisley and Kerslake are currently in litigation with the Osbournes over production credits and financial compensation for their work on Diary of a Madman. But Ozzy claims that Randy also had a role in his decision to fire the bassist and drummer. “Randy never liked Lee Kerslake,” Ozzy states. “And Bob was always intimidating him. And I can remember that Randy’s mum came to him and said, ‘What the fuck are you playing with those fucking idiots for?’ I was sitting next to Randy’s mum at the time. And she said, ‘What’s wrong with you, Randy?’ Then Randy said, ‘I think I’m gonna leave the band.’ I asked him why. We had a chat apart one day and he said, ‘The band is just a lot of geeks. You drink too much.’ I said, ‘Well, that’s just me. But what do you mean “a band of geeks”?’ And he said, ‘Look, how are we gonna conquer America with that fucking lot?’ ”

Rhoads suggested his old Quiet Riot pal Rudy Sarzo as a replacement for Daisley. And Tommy Aldridge was a drummer that Ozzy had known and admired for years. A veteran of Black Oak Arkansas, as well as Pat Travers’ and Gary Moore’s bands, Aldridge had first met Ozzy back in the Seventies, when Black Oak Arkansas opened for Black Sabbath.

The appearance of Sarzo and Aldridge meant that Randy was no longer the rookie of the team. “I depended on Randy just to get a feel for surviving the sometimes chaotic world of Ozzy,” says Sarzo. “It was my first experience playing in an arena band, so I was as green as they come. Randy had already been with Ozzy and Sharon for about two years. There were basic questions I had, like, ‘Why are they doing this or that?’ And he’d say, ‘That’s just the way they are.’ ”

“There was a lot of upheaval going on between Ozzy and Sharon at times,” says Tommy Aldridge. “That’s inevitable when you hook up two people as volatile as them. So there was a lot of drama going on.”

Perhaps too much drama for Randy Rhoads. The guitarist’s childhood friend Kelly Garni would sometimes get calls from Randy out on the road. “It’s no secret that he was trying to get out of Ozzy’s band,” says Garni. “After struggling so much for success, I think it was a big letdown for Randy when he finally got there with Ozzy. I don’t think he enjoyed being famous. He didn’t say too much about it, just that it was really grueling and that there’s a lot of weird people out there—which is what Ozzy attracted. Things like a guy coming backstage with a dead goat and saying, ‘Here, I brought you this as a sacrifice.’ That kind of thing really put the sap on Randy’s head. He didn’t understand that.”

But Sharon didn’t see it that way. “Was Randy disturbed by all that? No way. We all used to laugh about it. Randy had such a great sense of humor. He would find humor in everything.”

While the Sarzo-Aldridge lineup never made a studio recording with Ozzy, a live show from ’81 was captured on tape and released in ’87, five years after Rhoads’ death, as the Tribute album. And while Ozzy’s intentions in releasing the disc may have been sincere, Tommy Aldridge feels that Randy would not have been pleased to have people hear that particular tape. “Randy and I both hated the recording,” says the drummer. “It’s sloppy. It’s all over the ranch. I have boxes of board cassettes that are better than that.”

Another thing that Rhoads wasn’t particularly crazy about was having to play Black Sabbath material every night as part of Ozzy’s live set. “Randy understood that there is a legacy to Ozzy prior to his solo career,” says Sarzo. “He knew the importance of doing those songs. But I wouldn’t go so far as to say that was his favorite part of the show. After spending an hour onstage playing the Blizzard and Diary of a Madman songs that he cowrote with Ozzy, Randy just felt uncomfortable doing Black Sabbath songs, which were not really his style.”

“Randy was most disheartened to have to play ‘Iron Man’ and all those Black Sabbath tunes,” Aldridge confirms. “Neither he nor I were big Sabbath fans. Sometimes there were train wrecks on those songs, only because we were not that diligent about putting them together, to be painfully honest.”

While Rhoads may or may not have been freaked out by Ozzy’s morbid Sabbath followers, it’s certain that, toward the end of his life, he was certainly looking to a musical existence beyond touring around with heavy metal’s number-one madman. His interest in classical guitar had grown obsessive over the years, as Rudy Sarzo witnessed. “From the start of the Diary of a Madman tour on December 30, 1981, up until the time Randy died, every time we arrived in a new town he would take out the yellow pages, look for a music school and line up a classical guitar lesson. I would say 99 percent of the time he knew more than the teacher. Sometimes he would wind up paying for a lesson that he would give rather than receive.”

“Not long after I joined the band,” says Aldridge, “Randy confided in me that he had aspirations to do something else other than play with Ozzy. Just before his death, I know he wasn’t the happiest camper out there.”

According to Ozzy, Rhoads confessed as much to him on the final night of his life, as the band traveled from a gig in Knoxville, Tennessee, en route to a show in Orlando, Florida. “We’d just got Diary going,” says Ozzy. “Blizzard was happening. We were filling up arenas. And Randy turns to me on the bus and says, ‘I want to quit rock and roll.’ I said, ‘What?’ I asked him, ‘Are you fucking serious?’ He said, ‘Yeah, I want to go to UCLA to get a degree in classical music.’ I said, ‘Randy, put your head on right. Make your money in rock and roll and then when you get enough dough you can fuckin’ buy UCLA.’ But that wasn’t Randy.”

As it turned out, Rhoads never had to decide between Ozzy and UCLA. The 600-mile bus ride from Knoxville to central Florida was to be his last. The horrific events that took place on the morning of March 19, 1982, are still vivid in the minds of those who survived them. The band had been traveling all night in order to make a gig in Orlando: the Rock Superbowl XIV festival with Foreigner and UFO. The bus driver, 36-year-old Andrew Aycock, had persuaded Sharon that it was necessary to make a stop at the Flying Baron Estates in Leesburg, Florida, to obtain spare parts for the vehicle. Aycock lived there, and the stop would enable him to drop off his ex-wife, who had been traveling with him.

The Flying Baron Estates, according to Sharon, belonged to Jerry Calhoun, who owned the bus company, Florida Coach. “It was a huge piece of property—private property—and there were two houses on it [one owned by Calhoun, the other by Aycock]. There was also a little landing strip with helicopters and small planes.”

The bus arrived at the compound in the early hours of the morning. Aycock, also a licensed pilot, talked the band’s keyboardist, Don Airey, into going up for a spin in one of the aircraft on the site: a small, single-engine 1955 Beechcraft Bonanza F-35. In some accounts of the incident, tour manager Jake Duncan is also said to have been on this flight. At this point, most of the band and crew members onboard the bus, including Rhoads, were still asleep. But Tommy Aldridge remembers being awakened by the sound of the airplane in flight. “I kept hearing the plane fly overhead. That’s when Don Airey had gone up with our bus driver. I was trying to go to sleep, but the plane was so loud it was irritating.”

After a brief joyride, the plane landed. Airey got back on the bus and apparently persuaded Rhoads to go up on a second flight, despite the fact that the guitarist had a well-known fear of flying. Fifty-eight- year-old Rachel Youngblood also agreed to board the plane. The band’s seamstress and cook, Youngblood was an old friend of Sharon’s, having worked as a domestic in Don Arden’s home when Sharon was growing up. Rhoads also invited Sarzo and Aldridge to join him and Youngblood on the plane. Neither one accepted.

“Randy woke me up and tried to get me to come on the plane,” Sarzo recalls. “That was the last time I saw him. Rachel was with him. She was a wonderful woman. I can still remember the smell of the chili she used to cook for us on the bus. She thought it would be a special occasion for her to go up on a small plane, so she got all dressed up and everything. The pilot knew that Rachel had a heart condition. So the pilot told Jake that it would be just going up and down. Nothing fancy. Nothing crazy, right? And that’s why Randy had said, ‘Well, in that case, I’ll join you guys. I want to take some photos.’ Randy loved taking photos, and he really enjoyed being in Florida. So he went up there, basically, just to take a photo.”

“Randy actually stuck his head in my bunk when he was going off the bus to get on the plane,” Aldridge remembers. “If I recall correctly, I said to Randy, ‘That guy’s been driving a bus all night. I don’t think he has any business flying a plane.’ ”

Apparently no attempt was made to awaken Ozzy or Sharon to invite them onto the plane, a detail that haunts Ozzy to this day. “Without a shadow of a doubt in my mind,” he says, “I know that, had I been awake at that time, I would have been on that plane with Randy.”

Aycock, Rhoads and Youngblood left the bus, boarded the plane and took off. Sarzo went back to sleep, but Aldridge remained awake. “I tried to get back to sleep,” says the drummer, “but the plane just kept getting louder and louder. I got up to fix a cup of tea, since I couldn’t sleep because of all the racket. I was leaning against the microwave, mixing my tea and—ba-da-boombam!— all of a sudden there was an impact. It didn’t seem that big, but there was a strong smell of fiberglass. The top section of those Greyhound Eagles at the time was essentially made of fiberglass. The wing tip had hit the side of the bus, and I remember the bus driver’s [ex-wife] was standing in the doorway of the bus, scream- ing, ‘Oh my God, they’ve hit the bus, they’ve hit the bus!’ ”

The impact jolted Sarzo awake. “I jumped out of my bunk and went into the lounge,” the bassist remembers. “There was glass all over the place. I looked to my right and saw Jake Duncan, our tour manager, down on his knees pulling his hair out, crying, ‘They’re gone, they’re gone!’ ”

The left wing of the plane had clipped the back of the bus at about five feet two inches above ground level, by the estimation of Sarzo, who later stood beside the bus and measured the gash against his own five-foot-seven height. After striking the bus, the plane flipped over, severed the top of a large pine tree and crashed into the garage of a large house near where the bus was parked.

“I go running out of the bus and the [driver’s ex-wife] is screaming,” Aldridge resumes. “I yelled, ‘Who’s on the plane?’ And she said, ‘Randy and Rachel.’ I think at that point I started kinda numbing out. At 7:30 in the morning it was really muggy and hot. It all seemed surreal. We were in the middle of nowhere. I looked to the left and we had parked the bus in the cul-de-sac drive of this big antebellum-looking southern home. I don’t see another house anywhere. I’m trying to figure out where the heck we are and what the heck we’re doing here. And then I see smoke coming out of the house. So I go running around the side of the house and the garage door was open. I stuck my head in the house and there was a man sitting there in his underwear reading the paper. I ran in and said, ‘Your house is on fire!’ And he just kind of looked at me wide-eyed and sat there. I don’t know if he was deaf or he was just shocked to see a guy like me running into his house in the middle of the morning. I went out and ran back around to the side of the house and by that time the whole garage was in flames. When I had first looked at the garage, you could still see the outline of the plane. But it wasn’t that way for long.”

“The last thing we remember was being on the fucking freeway,” says Ozzy, “and the next thing we know we’re in this fucking field. And I didn’t know where the fuck we were. I thought we’d just rolled off the fucking freeway. And I couldn’t find the freeway, you know? And everyone’s pointing at this fucking big colonial house on fire. I’m going, ‘Where is everybody?’ I’d just been asleep on the bus. Sharon was out of her mind.”

“Sharon was visibly very upset with Jake Duncan,” Aldridge recalls. “ ‘How could you let that baby get on that airplane?’ she was screaming. But it wasn’t Jake’s responsibility. It was a day off and people were doing what they wanted to do.”

“Everyone was in total shock,” Sharon recalls. “You have to realize it was Randy and Rachel, who was my best friend in my life. They were both missing, and I kept screaming and screaming, and everybody was terrified. Nobody could talk. Most of them were in a seated position on the grass, just crying.”

Three bodies, burned beyond recognition, were later recovered from the area in and around the razed garage. Rhoads’ remains were identified by the jewelry he was wearing, Aycock’s via dental records. Toxicology reports later revealed that Aycock had cocaine in his system. Nothing stronger than nicotine was discovered in Rhoads.

“There were some theories that [Aycock] was trying to kill his ex-wife and commit suicide at the same time,” says Aldridge. “But I don’t believe that. What I believe is that he got too close to the friggin’ bus. I think that his flying skills had been somewhat compromised by the fact that he was up driving the bus all night. And I know for a fact that he wasn’t unassisted in being able to stay awake all night. I never told anyone this before, but I found a big freezer bag filled with cocaine stashed on the bus, beside the driver’s seat. I knew there was something up there ’cause [Aycock] was always tweaked, you know? So I pulled the top off the instrument panel to the left of the driver’s seat, where all the knobs and switches are. And there was a huge bag in there. I’d never seen that much before. The last thing I wanted to happen would be for some redneck Florida cop to come out and find drugs on a rock band’s tour bus. So I took the bag and threw it in the woods. I don’t know if that was the right thing to do or not, but I thought it was the best thing under the circumstances.”

Numb with grief, Ozzy and Sharon decided to continue the tour, albeit reluctantly. “I said to Sharon, ‘It’s over,’ ” Ozzy recalls. “ ‘This is a warning, a sign that my career is over.’ And Sharon yelled at me. She goes, ‘No, we do not stop now. Because Randy would not have liked it that way.’ ”

Guitarist Bernie Torme filled in for Rhoads on a gig at Madison Square Garden in New York. Then Brad Gillis finished out the tour on guitar. “That Madison Square Garden show was the toughest I’d ever done,” says Sarzo. “’Cause Randy had really looked forward to playing the Garden for the first time. It became very hard to get up onstage every night. Everything was the same—the staging, the set list—but Randy was missing. I never got rid of that feeling.”

“Sharon took it real, real bad for a long time,” says Ozzy. “She couldn’t listen to the set. She’d have to leave when we started playing the old songs. Or we’d be moving house and she’d find a piece of Randy’s clothing. It’s fuckin’ weird, man.”

Some four months after Rhoads’ death, Ozzy’s divorce with his first wife was finalized. He and Sharon were married. “But it was a bittersweet occasion,” says Sharon. “Yes, it was one of the best things that’s ever happened to me in my life. Yet Randy and Rachel weren’t there. And I so wanted them there when we were married. Because they had gone through so much with me and Ozzy and our crazy relationship. I wished they could see that we ended up together.”

But Tommy Aldridge delivers perhaps the best eulogy for his fallen bandmate. “They say no one is irreplaceable. That’s bullshit. Randy Rhoads is irreplaceable.”

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.

“I get asked, ‘What’s it like being a one-hit wonder?’ I say, ‘It’s better than being a no-hit wonder!’” The Vapors’ hit Turning Japanese was born at 4AM, but came to life when two guitarists were stuck into the same booth

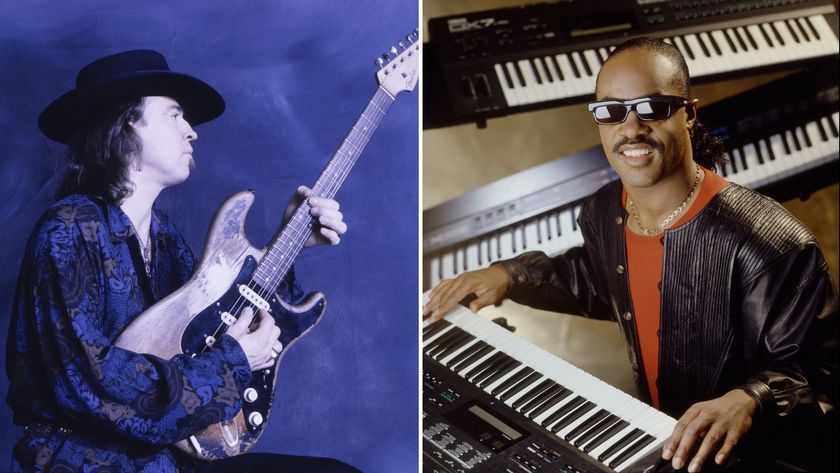

“Let's play... you start it off now, Stevie”: That time Stevie Wonder jammed with Stevie Ray Vaughan... and played SRV's number one Strat

![[L-R] George Harrison, Aashish Khan and John Barham collaborate in the studio](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/VANJajEM56nLiJATg4P5Po-840-80.jpg)