Out of the woods: the environmental challenges facing guitar makers

Traditional tonewoods are under pressure. Can luthiers create a new generation of planet-friendly acoustic guitars?

Where’s your next acoustic tonewood coming from? It’s a question that’s been getting harder to dodge for some years – and especially since the multilateral wildlife treaty CITES moved in 2017 to protect a handful of wood species that happen to be favoured by acoustic guitar makers and players.

In truth, the trade clampdown was just the latest sign that business as usual is no longer an option for traditional tonewoods – the tropical species such as rosewoods and mahoganies, and mountain-grown softwoods like Sitka spruce. Rising prices, tightening supplies, falling quality, ecological pressures… all have been in play for some time.

But as pressures to innovate mount, what’s next for music woods? We’ve spoken to acoustic guitar builders, from major American brands to mid-sized European companies, and independent luthiers, as well as forest researchers and campaigners, about how they’re responding to questions around supply, quality and sustainability of tonewoods – and whether buyers are ready for change.

CITES strikes

It’s early 2017. There’s a virtual freeze on imports and exports of the entire rosewood (dalbergia) genus. Guitar builders Michael Bashkin and Ervin Somogyi are chewing the fat on the podcast Luthier On Luthier.

Bashkin: “I really think we’re at an inflection point now where it’s not just the guitar-making community but also the guitar-buying community that realises we have been operating off a limited resource and one that could have been used sustainably but has not been. And I think that’s going to force some changes.”

Somogyi: “Well, I would hope so.”

The limited resource that they’re talking about is wood – and it includes species that generations of makers and players have come to regard as essential to great acoustic guitars. So powerful is the reputation of those species that many think it’s a barrier to change.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The industry has done “too good a job of convincing the vast majority of guitar players that high-end acoustic guitars must be made from rosewood, mahogany, ebony and spruce,” says Martin Guitars CEO, Chris Martin IV. “And, yeah, they work – but other woods work also.”

Somogyi sounds more wishful than hopeful about the prospects for change. So how are guitar makers reacting to the turning of the screw on traditional tonewoods, of which the 2017 CITES listing was just the latest and sharpest twist? How far and how fast are we prepared to move on from the old formula?

We’ll come to that in a little while. First, a recap of rosewood’s CITES moment.

Previously, on the rosewood files

“They went out fishing for tuna and they caught a dolphin,” says Chris Martin. When the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) cast its net around rosewoods, bubinga and kosso in early 2017, its aim was to protect a number of exotic species from being wiped out – though not, it’s generally agreed, by instrument makers, who use a tiny sliver of global timber.

The feeding frenzy in the forests seems to have been driven by surging Chinese demand for red ‘Hongmu’ furniture. CITES was trawling for chairs; guitars were by-catch.

Fast-forward two years and guitars are off the hook. Following a period of outcry and consternation among makers, buyers and sellers, CITES dialled back: as of the end of November 2019 it no longer requires musical instruments or parts of instruments containing rosewoods to have permits to cross international borders. (This doesn’t apply to Brazilian rosewood, which is still highly restricted.)

So, as you were? Up to a point. Certainly, the tweak to the trade regime will mean private buyers and sellers not having to sweat over documentation for each instrument containing rosewood. It will probably speed up delivery times for buyers.

And it could be a relief to officials who had reportedly been swamped with CITES permit applications. A few indie luthiers might be calming down, too – some had apparently threatened to burn their pre-CITES rosewood stash in protest at the clampdown.

This is the first D-28 ever made by Martin, in 1932. With its Brazilian rosewood body and spruce top, it set the tone for many acoustic guitars that would follow. But do high-end guitars really need to be made of such traditional tonewoods?

Andrew Thoms, executive director of the Sitka Conservation Society, says that the quality of Sitka spruce is dependent on the tree growing in an area that's had the "ecological luck of the draw" for the past 700 years.

"“I know where there are some stands of trees of that quality here around Sitka," he says. "To get to them I have to paddle in my kayak or take a boat for a couple hours and hike through a forest and through a bear estuary and then get to a flat bottom-land forest, and it’s also the prime habitat and the ecological heart of the forest. And those are also the places that have been targeted by logging over the past 60 years."

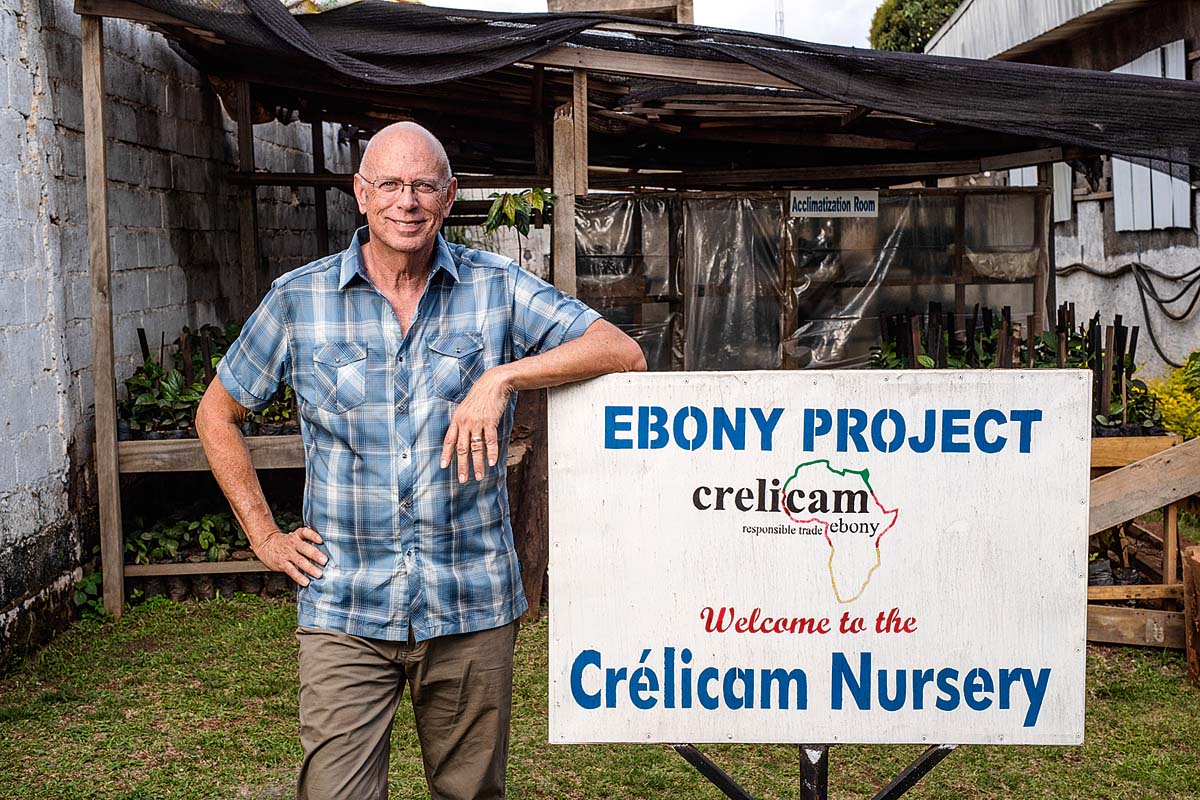

Bob Taylor of Taylor Guitars at the Crélicam Nursery. Taylor started the Ebony Project in 2011 to create a sustainable supply of the tonewood.

Not everyone welcomed the exemption for finished instruments. Environmental experts have pointed out that it could become a loophole, weakening protection of the species.

Bigger manufacturers, meanwhile, had generally been taking the paperwork on the chin, as Taylor Guitars founder Bob Taylor explains. “We’re completely happy to operate under the umbrella and the permit structure of CITES for all the wood we bring in. But once we turn it into a guitar we would like the dealer and consumer to be free of that obligation as they’re not able to honour that obligation, and it makes criminals out of people who had no idea what they did wrong.”

What will CITES do next?

For now the onus is off consumers and retailers. But guitar makers will be preoccupied with the detail of the CITES process whenever it moves to protect the next species, and the next. And that’s the enduring point: rosewood was a rehearsal.

As if to underline the point, at the same time as easing the net around rosewoods, CITES tightened up regulation of the entire Cedrela (cedar) genus. That includes Spanish cedar (Cedrela odorata) – another wood that’s important to the guitar trade.

Lots of Martin guitars, for example, include Spanish cedar as ribbon lining, and it’s a staple for the classical guitar industry. As with rosewoods, musical instruments containing Spanish cedar won’t need a CITES permit, but sawn cedar from Central America will come under greater scrutiny from August 2020.

While major guitar makers were expecting these latest changes, and timber suppliers seem relaxed about them, worries over the health of species are more likely to intensify than go away. And so the question is not if but when CITES will reach out to protect more.

The current state of geopolitical forces are not in favour of well-maintaining tropical forests

Michael Bashkin

Looking ahead to the next full CITES meeting in 2022, Taylor’s sustainability lead, Scott Paul predicts “an uptick in commercially traded trees being listed and some of those are destined to be used in musical instruments. We had Brazilian rosewood in ’92, big-leaf mahogany in 2002, then the entire rosewood genus in 2016. In three years I predict you’ll see another species or two, and in another three years you’ll see another three.”

The CITES action on rosewood and cedars is just one marker of the mounting pressure on wild species and habitats. You’ll have heard that we’re in the midst of the sixth mass extinction on Earth. And the ongoing ravaging of healthy forests matters a lot: they provide oxygen, biodiversity, homes and livelihoods to hundreds of millions of people, and they lock up billions of tonnes of carbon.

The world’s forest area shrunk by over three per cent in the 25 years to 2015, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation, with industrial-scale farming and ranching leading the rampage. And although the rate of loss has slowed in recent years, that’s thanks to legislation, enforcement and an expansion of the area under forest management plans – and these things can be undone.

Take Brazil, where the government looks bent on opening the Amazon to renewed exploitation: a decade of decline in deforestation halted in 2019 with a spike in illegal logging and fires.

The guitar industry can no longer be passive observers… We can help to educate policy makers

Bob Taylor

Guitar makers know it. Michael Bashkin was a forest scientist before he started turning trees into guitars. “To sum up the state of the world’s forests in two words?” he says. “Not good. There’s certainly the knowledge and management skills to manage tropical forests efficiently, responsibly and legally. But the current state of geo-political forces, global economics, are not in favour of well-maintaining tropical forests.”

Less of what we want

Even if the only thing that mattered was what woods are left over for guitars once the ranchers, miners, loggers and road builders have taken their cut, we’d still be lamenting what’s happened to forests since our great grandparents sat under some shady bough. Because for several major tonewoods, the story of the past three generations is one of declining availability of the best specimens, which usually means the oldest.

“Generally speaking, better quality wood was available decades ago,” says Michael Bashkin. “The Honduran mahogany I can buy now is really not of the same quality as the Honduran mahogany I was buying 20 years ago.

“Mahogany as a species is not endangered if you look at a count of individuals,” he adds. “But the larger and old-growth trees have been preferentially harvested and, over decades, if not centuries, the effect has shifted the age and size to younger, smaller trees and what most guitar builders would regard as lesser quality wood.”

It’s a similar tale for other species. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) casualty list makes worrying reading for many exotics that happen to wind up in guitars: many are critically endangered; Cuban mahogany and wenge – endangered; Spanish cedar, cocobolo, Macassar ebony, khaya (African mahogany), Honduran mahogany, okoume, sapele, utile, walnut (claro) – all vulnerable.

Gaboon ebony (diospyros crassiflora) was tagged as endangered until evidence in 2017 suggested millions more trees were standing in west Africa than previously thought. So it’s now listed as merely vulnerable – at “high risk of extinction in the wild”.

It’s not only tropical woods that are causing alarm. Specialists have worried for some time about Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis) – the straight-grained giant favoured for guitar tops.

“Sitka spruce as a species is of least concern in terms of how much is out there, but the tonewood-grade quality of those trees is extremely rare – they harvested most of that already and there aren’t many virgin stands of trees left,” says Andrew Thoms, who heads up the Sitka Conservation Society in Southeast Alaska’s Tongass National Forest (Thoms explains more on this in ‘Good Wood’ opposite).

Now, he says, “they are clear-cutting in the Tongass to get to tonewood and other high-grade quality. Is it right to clear-cut 2,500 acres to get 200 trees that are of music wood quality?”

Pressure from the US administration to scrap legislation currently protecting vast areas of the Tongass from exploitation only adds uncertainty to the picture. Guitar builders worry also about the impact of global warming, disease and fire.

Bob Taylor has “big-time concerns over Sitka”. On its 500 series, Taylor is already deploying Canadian-grown Lutz, a hybrid of Sitka and White spruce. He describes this tonewood as “pretty global warming-resistant, with some of the size of Sitka, great tonal qualities”.

Taylor’s use of Lutz is one example of one major brand looking to futureproof against the squeeze on traditional tonewoods. Next issue, find out how builders, from bespoke luthiers to the big names, are adapting, and what that means for the guitars we play.