Mikael Akerfeldt on 20 years of Opeth's Blackwater Park: "I was bitter and beaten down – I didn’t have much hope for us. All I knew was I liked the music I’d written"

The Swedish prog vet reflects on the gear picks, hybrid techniques and creative vision that led to the band's boundary-smashing landmark album

Widely regarded as one of the greatest progressive metal records of all-time, 2001’s Blackwater Park was the album that saw Opeth step out of the underground and into the limelight, establishing themselves as one of the most exciting prospects in heavy music.

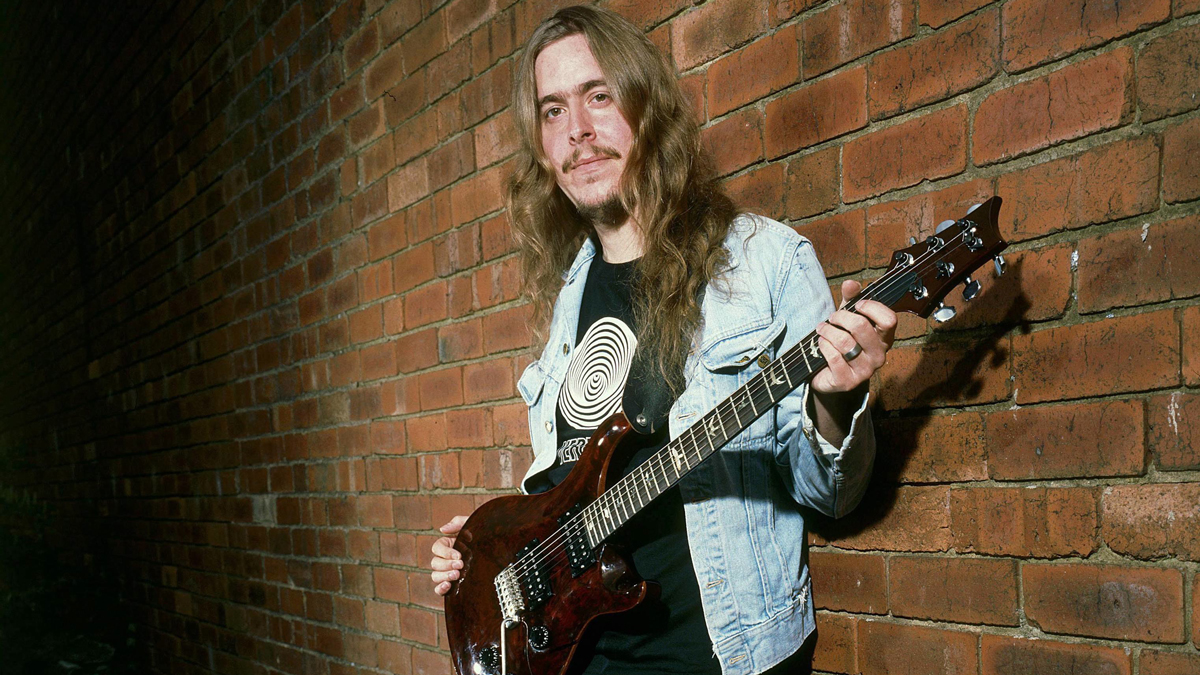

More stylistically diverse than the four albums preceding it, with a crisper sonic clarity courtesy of Steven Wilson’s production treatment, its eight sprawling tracks showcased the wild breadth of singer, guitarist and leader Mikael Åkerfeldt’s imagination – then just 26 years old.

Frenetic death metal and melodic symphonies entwine and then fade into ethereal acoustic lullabies, with moody jazz interludes and folky fingerpicking softening the attack to majestic extremes. And despite the finger-twisting assault course of ideas and intricate embellishments detailing many of its riffs, there’s a striking fluidity to match the flawless execution.

Album number five would pave their path to world recognition and the accolades that come along with it, though at the time life was very different for Åkerfeldt – who, by his own admission, felt like he was on the road to nowhere…

“It’s weird talking about these songs now being 20 years old,” he tells Guitar World, speaking from his home in Stockholm, Sweden on a warm summer’s day.

“I was living in a small one-bedroom flat and didn’t really have much going for me or the band. We’d done four records prior and there was little interest, I would say. I mean, the people who liked us really liked us but there were too few.

“We never had any feedback or any help. So to me our future looked bleak... just like the song! I didn’t have any high hopes, but I was proud of the material I’d written. I’d also kinda come to terms with the idea that ‘it’ might not happen for us. When we started, I was young and figured a record deal meant it was pretty much done… I wasn’t so much of a fuck-up or failure after all! But that didn’t turn out to be true. We’d done four albums and I was a complete loser [laughs].”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

It’s hard to imagine the Opeth leader thinking of himself in that way, but that sense of never quite arriving was something that weighed on his mind. Though he appreciated their underground success, he couldn’t just shake off the feeling his band could be doing a lot better.

“You’d compare yourself not even with musical peers but people from your school,” he continues. “Old classmates, who you might run into from time to time and they’d have flourishing careers. Even if I thought their careers sounded boring, at least they had something to survive on. I was bitter and beaten down, I think, writing for this record. I didn’t have much hope for us. All I knew was that I liked the music I’d written…”

Not that there was much of it. A lot of the tracks came together at Studio Fredman almost haphazardly, with many parts being written and rewritten only moments before being recorded. Åkerfeldt’s logic was that the snippets of music he’d already come up with were a good enough indication of how this album could turn out – it was just a case of getting started and letting creativity dictate where to go...

“Most of the tracks had some major changes,” he explains. “I’d demoed parts of Bleak, Harvest, The Drapery Falls and perhaps the title track at a friend’s house, but I came up with a lot of stuff in the studio. This album and its predecessor, Still Life, were done like that and left up in the air. It was a stepping-stone into that way writing and recording, because for the following records, Deliverance and Damnation, I had no songs!

“I was brimming with confidence in some weird way, so decided to make two albums with no songs written, which was a bit rich! I figured I was some type of genius who could come up with all of this music overnight. That turned out to be a bad decision for the sessions [laughs]! For Still Life and Blackwater Park, it seemed to work. I had so much music inside of me...”

From what we know, the main guitars on Blackwater Park were your PRS CE24 and a Gibson Les Paul Custom...

“That sounds about right. Peter played a 1973 Les Paul Custom – he wanted one made the year he was born. It was in beaten shape, the neck had been broken and fixed up but it was a pretty good guitar. I’d bought my first PRS from Anders [Nyström] who plays in Katatonia...”

And then for acoustics, you had a Seagull S6CW acoustic and a Yamaha 12-string...

“I loved that Seagull guitar. I don’t know where it is now. Maybe [Opeth co-guitarist] Fredrik [Åkesson] has it! It was in two pieces when I got it: the neck was completely broken off the body. I worked in a guitar shop in the early '90s and another shop distributed these Canadian Seagull guitars...

“I had a friend there and asked if I could borrow one for recording. He gave me this broken acoustic. I was actually thinking of going to a landfill and throwing it, but I decided to fix it up. I glued it back together and did a lot of work on it, so it looked awful but sounded nice and had good intonation. There was a big bump on the 14th fret but it was a nice guitar, overall. I can’t remember a Yamaha, but there might have been one.”

You started using Laney amps for your live shows around this time, but what amps are we hearing on the record?

“Yeah, I think we landed the Laney endorsement just after Blackwater Park was finished, right around the tour. I don’t think we recorded through Laneys, though. We were at Fredrik Nordström studios and he had just acquired an Engl amp. He told me it was the kind of thing Ritchie Blackmore would use and I said, ‘Okay, that’s great… perfect!’ I think he also had a 5150, but I can’t remember which we used where.

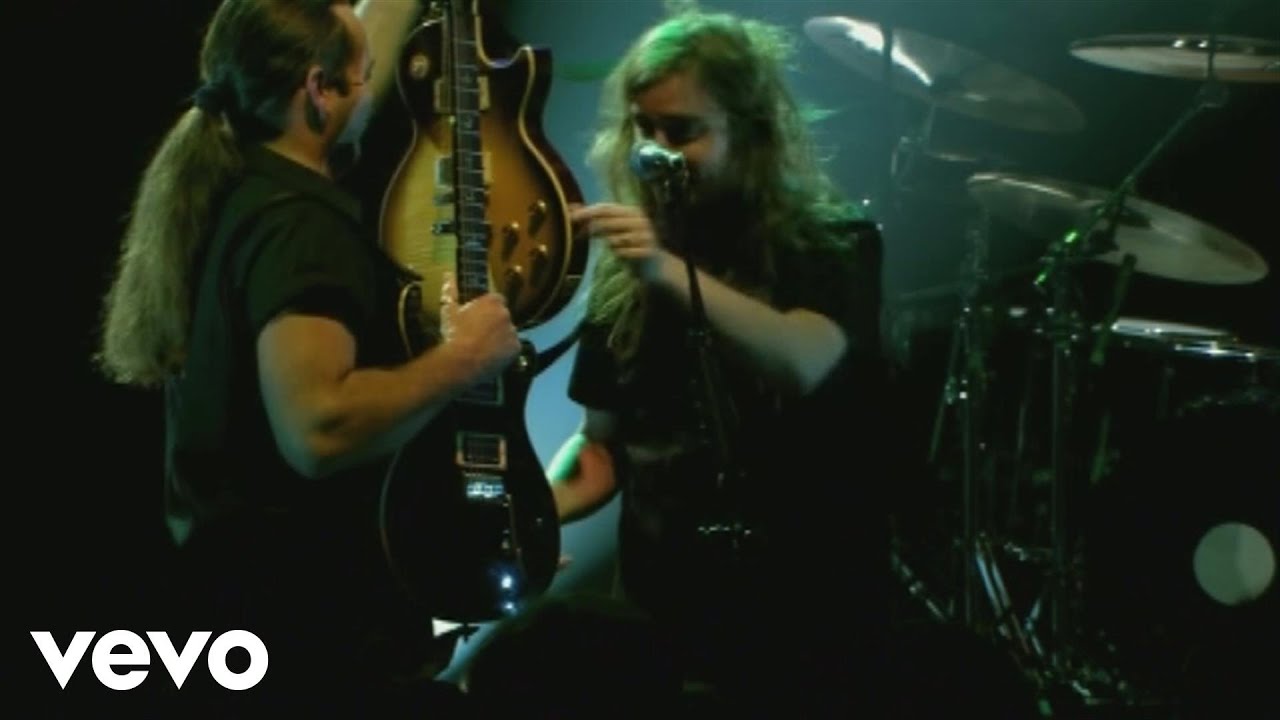

“In those days, we were tracking four guitars and [ex-member] Peter Lindgren would play his parts through one amp and I’d use a different one. I can’t even remember if I put down most of the rhythm guitars. But I was trying to incorporate Peter in the process as much as possible. There were times before, like on our third album, where he just didn’t cut it. And he knew it – so he’d give me the guitar saying, ‘I can’t do this bit – you do it because we’ve already spent an hour here!’”

It doesn’t sound like a huge amount of effects were used, other than some tremolo and EBow on The Drapery Falls, and maybe some phaser here and there...

“The EBow I bought for Still Life ended up all over that record. Maybe we went a bit overboard on that album and on tracks like this [laughs]. Steven Wilson held the reins a bit when I was trying to put EBow on everything, which is why it’s more subtle on Blackwater Park. And it’s similar with me and the [Electro-Harmonix] Small Stone – I had one of the big green Russian ones. I still have one today, that’s how much I love that sound.

The Leper Affinity had a bit more pace so we made it the opener. You always want to smack the listener open-handedly in the face!

“I don’t remember a tremolo pedal, so it was probably a software thing that Steven had. I wish I could remember these things but I honestly didn’t know I’d be talking about this 20 years later [laughs]. Steven was so advanced; he could find what he was looking for in a couple of seconds. If it sounded good, we’d just move on.

“In those days, I wasn’t so meticulous about having the ‘real deal’. If it sounded good, that would be enough for me. When Fredrik joined, though, we transformed into one of those ‘real deal’ bands because he’s so into gear.”

The album opener, The Leper Affinity, has some truly exquisite harmonized guitars before the acoustic interlude where you sing ‘Lost are days of spring’...

“I might have demoed parts of this song before we recorded it, with no vocals and a shitty sound. It would tend to be short segments of songs that I would record. I came up with the acoustic section just from noodling.

“We decided to put this song first because it’s a bit more ‘upbeat’ in tempo than, say, the title track which is a fast double bass song, but not really in terms of bpm. The Leper Affinity had a bit more pace so we made it the opener. You always want to smack the listener open-handedly in the face!”

Bleak has some similar moments, going from metallic thunder to chordal interludes like where you sing, ‘Help me cure you’...

“It’s a good part. The main thing I remember is that the demo version had pretty shitty opening riff. It was bad. Listening back to it, I was thinking how our label could even agree to release it.

“But then [ex-drummer] Martin Lopez ended up playing me something by Kurdish singer called İbrahim Tatlıses. I guess it was Kurdish pop music, but to my ears it sounded evil. It had notes in their scales that you didn’t really find in Western scales, with bends that were in between notes. I immediately rewrote the beginning of Bleak...”

Which has quite a Phrygian Dominant feel thanks to its usage of major 3rds with minor 2nds and 6ths. To be honest, a lot of the music you’ve written over the years has felt more outside – incorporating elements of the diminished, melodic and harmonic minor scales…

Guitar is amazing: you can not know what you’re doing and that can somehow help you in more ways than it stops you

“I find a lot of inspiration in those kinds of sounds. I was a bit fed up of the standard kind of death metal. I was still discovering lots of progressive rock bands. I also loved what Rainbow and Deep Purple did with those kinds of notes. The same goes for Led Zeppelin. There was something magical about those intervals.

“I tried to incorporate that into Opeth from pretty much the start, and while it felt wrong playing a lot of those notes to begin with, by Blackwater Park I was well-versed in those kinds of scales. I started to use them more and more within my music. I still do, to this day.”

How exactly did you learn them?

“You stumble upon your favorite moods. After a while, it’s like you’ve taught yourself to go from playing pentatonic blues to something more Middle Eastern-sounding. And soon enough, that’s where your fingers will move automatically whenever you pick up a guitar. It’s not necessarily in my DNA, but it’s not far away.

“The same goes for jazz chords. I wish I had more theory knowledge – I usually find out what chords I’ve used after playing them, when people tell me… and I tend not to be listening anyway [laughs].

“I’ve been playing guitar for such a long time, and I don’t think I’m particularly good, but I can still find things on the fretboard I haven’t played before and sometimes things I haven’t heard before. Guitar is amazing in that sense. You can not know what you’re doing and that can somehow help you in more ways than it stops you [laughs].”

The solo for Harvest is quite different in feel to other leads, with a gypsy-led bounce before it ends up somewhere more bluesy...

“I wanted to surprise the listener with certain notes. Because the chords themselves are pretty standard – a lot of barre stuff, typical major and minor shapes. They weren’t hugely exciting in that sense. I wanted to write progressive weird crazy things and this song wasn’t that. But there was a nice melody and order to the chords. I knew I wanted a solo because one of my strengths as a guitarist, when I’m not shy, is to play slow and melodic.

“But I also wanted to play over something that wasn’t typical. I wrote it in the studio by fiddling around and seeing what fits – it was quite difficult. I couldn’t rely on my usual tricks. In the end, I think it came out pretty tasteful and exciting. It’s not your typical bluesy solo, and I love those too, but back then I was really trying to avoid moving in regular territory. It was my chance to dive into something weird. It worked... it didn’t fuck up the vibe of the song; it added something. It’s one of the solos I’m still happy with.”

The Drapery Falls has always been a popular live track, going from two-chorded simplicity as you sing ‘Spiraling to the ground below’ to those jarring tritone parts that creep up chromatically...

“That one came out pretty nice. It’s song I can still relate to 20 years on. I could have written it today, so I guess it hasn’t really aged in a way. Other things we’d done before that feel so remote now, I would never write that today. I’m just not that guy anymore. I must admit I wouldn’t have written the chaotic chromatic part now…

“I must have known it was a bit shit when I came up with it, which is why I decided to play it again one fret up to get even more dissonant. Honestly, that riff was probably something I never liked. It wasn’t even a riff, more just a part. If something was heavy but a bit bland – I guess my trick back then was to play it again a fret higher to make it really clash [laughs]!”

Dirge For November has some truly mesmerizing A-minor jazz ideas at the beginning and end...

“On Still Life, Peter didn’t contribute at all. He would never say anything, but I could tell he was not happy about that. I think it made him feel small, like I didn’t allow him. On Blackwater Park, he wrote a couple of riffs that we put in the heavier verses of Dirge For November, and I wrote the rest.

“It’s a bittersweet song because I guess that’s the last song we did together. And it’s actually my favorite from the record, just so dark and simple. We’d left it out, never really playing it live until we did the Blackwater Park anniversary shows.

“That’s when I realized it was a really fuckin’ nice song! Maybe it felt too sad to play, but it’s a very evocative track. This and Harvest are probably the ones I’m most proud of, while there are parts of others I think are really good. After two decades, I might wonder, ‘Why did I write that shit – it’s horrible!’ Other things still feel good and I can relate to, which is a nice feeling to have about your own music.”

There’s some great interaction between your acoustic and Steven Wilson’s piano on Patterns in the Ivy – the perfect duet to set up the grand finale of the title track...

“Yeah! It’s just a simple A minor type of thing. I think it was Steven’s idea to put piano on there and we were really happy, because we wanted him on the album… he was our idol! We hadn’t done any vocals at that point and he wandered over to the grand piano saying he might try something out. We said, ‘Yeah, knock yourself out!’

“I left that open space for his piano do to whatever it needed and it was one or two takes. And he’s not a pianist – I don’t think he’d ever call himself great at it – but he has this ability to play beautiful things. The first one was so good and we said, ‘That’s it!’ But he felt it wasn’t, so did another take that was almost as good with all the key moments. The first one, however, felt extra-magical, so that’s what got used.”

- The 20th anniversary reissue of Blackwater Park is out on July 16 via Music For Nations and available to preorder now.

Amit has been writing for titles like Total Guitar, MusicRadar and Guitar World for over a decade and counts Richie Kotzen, Guthrie Govan and Jeff Beck among his primary influences as a guitar player. He's worked for magazines like Kerrang!, Metal Hammer, Classic Rock, Prog, Record Collector, Planet Rock, Rhythm and Bass Player, as well as newspapers like Metro and The Independent, interviewing everyone from Ozzy Osbourne and Lemmy to Slash and Jimmy Page, and once even traded solos with a member of Slayer on a track released internationally. As a session guitarist, he's played alongside members of Judas Priest and Uriah Heep in London ensemble Metalworks, as well as handled lead guitars for legends like Glen Matlock (Sex Pistols, The Faces) and Stu Hamm (Steve Vai, Joe Satriani, G3).

“It combines unique aesthetics with modern playability and impressive tone, creating a Firebird unlike any I’ve had the pleasure of playing before”: Gibson Firebird Platypus review

“I met Joe when he was 12. He picked up a vintage guitar in one store and they told him to leave. But someone said, ‘This guy called Norm will let you play his stuff’”: The unlikely rise of Norman’s Rare Guitars and the birth of the vintage guitar market