Paul Stanley and Gene Simmons rate Kiss's lead guitarists and reflect on the band's history in this classic 2014 GW interview

In their five decades as a band, Kiss have had five lead guitarists. Here, the band's core members reflect on each of them – their strengths, their weaknesses, and how they meshed with the rest of the band

The following interview is taken from the April 2014 issue of Guitar World.

In this classic from the GW archives, Kiss's sole remaining original members – Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley – hold little back as they assess and reflect on the five musicians who have occupied the lead guitar slot in Kiss over the decades.

Ace Frehley

Gene Simmons: "As a musician, you have to hand it to him. He knew his stuff. And when he cared – the first three records, I would say – he was great. You can sing those solos. It was like opera. And the integrity of his style was instantly recognizable. As soon as he played, you knew it was him. That’s probably the highest compliment you can give to a guitar player."

Paul Stanley: "In the beginning, we just gelled as guitarists. And even today, I talk about Ace a lot. I’ll tell people, 'He really had the goods.' He can argue all he wants that he still does, or say whatever he wants to say the reasons are that he didn’t ascend to more. Everyone’s entitled to their opinion. But I saw somebody throw away a gift."

Simmons: "Before the drugs and the booze and everything, he was basically Ace, a lovable, loving guy. We all cared for him. I loved him. I love the straight Ace. But I fucking hate any drug addict. Because they’re possessed."

Vinnie Vincent

Stanley: "Vinnie had an incredible touch and an incredible knowledge of the guitar. But left to his own devices he’d hang himself. For somebody who could play so brilliantly and so tastefully, it became more about how much he could play rather than what he played. And, ultimately, I couldn’t understand what he chose to play. And that’s not taking into account all the other stuff about him, which I think has been well documented."

Simmons: "He was a much more accomplished musician [than Frehley]. Understood some jazz. Could play faster. He was a big fan of all that sort of hurricane machine-gun stuff. But he was not as pure in his personality. We wrote I Love It Loud together, although he hated me for telling him what to play in the solo. But the guy could write songs.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

"The guy could sing. He could play rings around most anybody. But with all due respect to Vinnie, it was a fucking nightmare. And it continues to be. That guy sued us 14 times and lost 14 times. But I wouldn’t wish his life on anybody. He’s had a lot of grief. A lot of trouble. And I feel sad that he didn’t understand the gift and the opportunity he was given."

Mark St. John

Stanley: "My classic story with Mark is that during the making of Animalize I sent him home one night to come up with a solo to one of the songs. And the next day he came back and played me something that was at least a start. Then I said, 'Play it again.' And he said, 'I can’t.'

"The guy could never play the same thing twice, because he was just puking notes. There was no structure to any of it. So I told him, 'Go home and listen to Eric Clapton. Listen to Paul Kossoff. Listen to Jimmy Page.' And he looked at me and said, 'I can play faster than them.' So that about sums it up. Check, please!

Simmons: "Mark’s guitar playing was like an angry bee flying around your head. The most irritating sound. And he would show you that his fingers could stretch 11 frets. He could play very fast, but he was all technique. He did not have a style or soul."

Stanley: "Obviously health issues derailed his being in the band [soon after recording Animalize, St. John developed Reiter’s Syndrome, an arthritic condition that left him unable to play], but I don’t know how long he could have been in the band. He was the poster child for, as far as I was concerned, not understanding what great guitar playing was about."

Bruce Kulick

Stanley: "For some people, Kiss started in the Eighties, and for them Bruce is the guy. He was a great team player and somebody who always wanted to do his best. He was also essential to Kiss becoming a Platinum-selling band again. His importance should not be minimized."

Simmons: "Bruce was the perfect guy for us at that time. And the irony is that he became the guitar player in Kiss after [his brother] Bob Kulick auditioned for the band. But Bob was more of a Neal Schon–type player, while Bruce was more flexible in his style. He could adopt and adapt.

"He could play fast, but he could also play with melody. And he was a nice guy. Not a great singer, but his strong points were his fingers, not performing. It would be like pulling teeth to get Bruce to open up onstage – to raise his arm up or do a Jesus Christ pose, that 'I’m so important thing.' That wasn’t his style. His strength was the guitar."

Tommy Thayer

Simmons: "I met Tommy when I produced two records for Black ’N Blue [Thayer’s Eighties-era glam band]. He was always organized and a solid, professional guy. What I didn’t know back then is that he was also in a Kiss tribute band, Cold Gin. So he knew Ace’s solos forward and backward.

"Tommy started off with us by helping to put together the Kisstory books. Then he helped with Kiss conventions. After that he was our road manager. When Ace left again, he became the guy. And he’s the best of all possible worlds."

Stanley: "Tommy’s a terrific musician – a great lead player and a very even rhythm player. The fact that he already had the Kiss stuff down, the fact that he worked with Ace on the reunion tour, that’s all moot. That just says that he technically knows the material. Tommy is much more than that. I love his playing. I love his work ethic. I wouldn’t want to play with anybody else."

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.

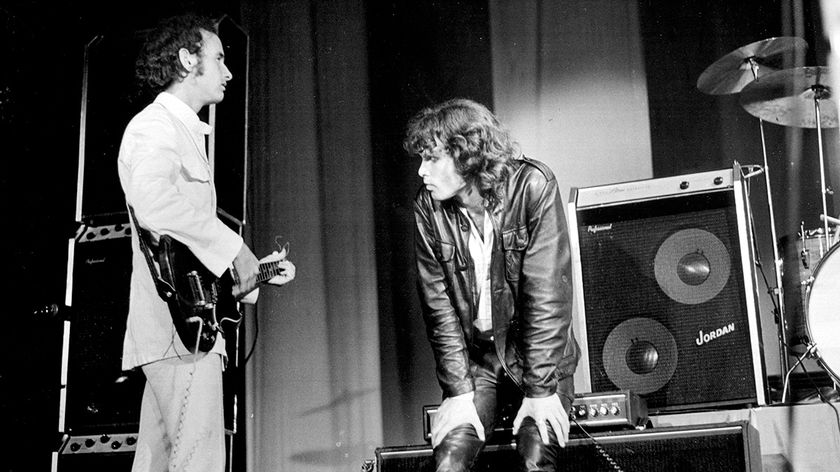

“That was one thing I wanted to get right with Oliver. I went to his house and made sure he knew how that one had happened”: Robby Krieger sets the record straight on how a Doors classic was really written – and what the controversial movie got wrong

“A guitar Eddie Van Halen gave me went missing for 18 years. So many really important guitars are stolen or disappear. We rarely get them back”: Jerry Cantrell opens up on his missing guitar fears, pushing beyond his limits – and why AI could never do AIC

Most Popular