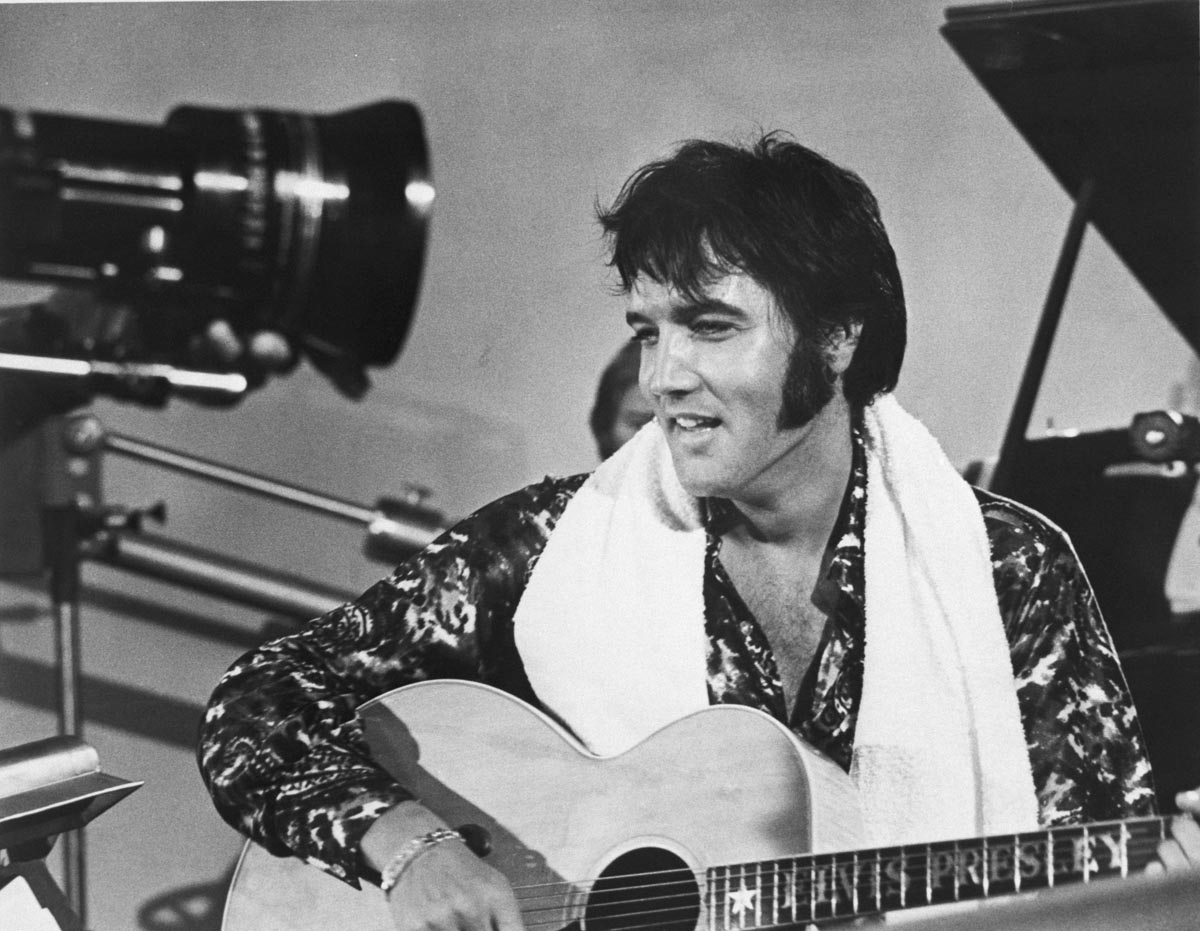

Norbert Putnam: ”Elvis was conducting us with his body language... that’s the reason those records have such a great feel”

Producer, author, and bassist Norbert Putnam looks back at the legendary Nashville Cats recordings with Elvis Presley

”I tell young musicians that we recorded 35 tracks in five nights, and they tell me that’s impossible!” snickers Norbert Putnam, bassist with Elvis Presley from 1970 to 1977.

The kids’ reaction is understandable: Even by the prolific standards of the Seventies, when bands routinely released two or three albums a year, that’s a work rate that beggars belief. It really happened, though, and it’s a privilege to speak today with a musician who saw it take place.

We’re talking to Putnam – ‘Putt’, as the late King called him – because RCA, Elvis’s record label for the last 65 years, is releasing From Elvis In Nashville, a new box set. These recordings come from a sustained five-night session at RCA’s Studio B in Nashville in June 1970, plus an additional one-off event in September.

Alongside the house band, the Nashville Cats – of which Putnam was a key member – Elvis did indeed cut 35 songs, live, and on peak form.

These songs went on to form three albums, That’s The Way It Is (1970), Elvis Country (I’m 10,000 Years Old) (1971), and Love Letters From Elvis (also ’71). The songs have been remixed to get rid of subsequent overdubs and orchestration, getting us closer to the original feel of Elvis plus band in an efficiently creative space.

Although we know now that within a couple of years of the Nashville session, Elvis sank into a state of poor mental and physical health that culminated in his death in ’77 at the age of only 42, Putnam makes it clear that the great man was firing on all cylinders in 1970.

Elvis was working out, and he was doing karate. His bodyguard Red West was there, and he and Elvis gave us a few karate demonstrations. They were pretty impressive, believe me

“You couldn’t see an ounce of fat on him,” confirms Putnam, now 78 and still taking occasional bass sessions. “He was working out, and he was doing karate. His bodyguard Red West was there, and he and Elvis gave us a few karate demonstrations. They were pretty impressive, believe me.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Elvis used to lean forward with his index and middle finger out, and throw a punch right at Red’s eyes. He could stop one inch from Red’s face, which scared the shit out of everyone, ha ha!”

Elvis was famously fond of guns, as you’ll know if you’ve read any of the sometimes damning books about him, and it wasn’t long before the subject of firearms came up, explains Putnam.

“Someone asked him, ‘Elvis, what do you do if someone points a gun at you?’ and he said ‘Red, get a revolver’. All of [Presley’s entourage] the Memphis Mafia carried a shiny aluminium camera case, and of course one of them contained weapons. So Red goes over to the weapons container and gets a revolver. He takes the bullets out– thank God – and assumes the position, pointing the gun at Elvis’s face.“

“Elvis leaps forward and does a karate chop across Red’s wrist, and the weapon goes flying across RCA B. Now, at the back of the room, our guitarist Chip Young had two or three guitars leaning against the wall, with the backs of the guitars facing outwards.

“So this gun goes somersaulting across the studio and goes right into the back of Skip’s beautiful, handmade Spanish guitar. He had paid a lot of money for that guitar, so I’m looking at it, and Chip’s looking at it, and then we all look back at Elvis.

In June of 1970, I’m sure he was taking what they called ‘medication’. Every hour, one of the guys would take Elvis into the bathroom, and we were not allowed to go in when he was in there

“All the Mafia were saying ‘Oh Elvis, that was great’ because they were paid to applaud everything he did, and Elvis goes right into another karate demonstration. Meanwhile Chip Young is having a heart attack because he’s paid several thousand dollars for that guitar, but then the guy who looked after Elvis’s money comes up to Chip, asks ‘How much for the guitar?’ and writes him a cheque on the spot!”

We’ve already talked about guns and rock’n’roll –we might as well ask about drugs. Did Putnam ever see Elvis taking the uppers and downers that eventually contributed to his death?

He pauses to consider before replying, “I don’t think he was taking hard drugs, but I can tell you that in June of 1970, I’m sure he was taking what they called ‘medication’. Every hour, one of the guys would take Elvis into the bathroom, and we were not allowed to go in when he was in there.”

“Then again,” he points out, “I’ve had a lot of music friends get hooked on drugs. There was one drummer I knew, a famous L.A. musician, who used to tie off his arm and shoot heroin five minutes before a session started.

“After he got the smack in his veins, he was totally normal. He led the band through the session and never made a mistake, because he’d built up some resistance. Maybe Elvis had that sort of resistance too, because he was always so sharp.”

You know what the popular history of Elvis Presley suggests: That he was a red-hot rock’n’roller in the Fifties, sank into a terrible movie career in the Sixties, and ended up a fat joke in a white jumpsuit in the Seventies.

Of course, there was more to him than these simple clichés. In 1970, Elvis was performing with maximum skill, still enjoying a wave of public appreciation after his 1968 Comeback Special, on which he had appeared lean and mean in black leather –and he was still only 35.

As Putnam tells it, the King was full of enthusiasm for music, and for life, when he walked into Studio B. “Back then, I was booked every night at RCA from six to nine PM and then from 10 to one AM. All the Nashville studios ran that way. I’d play sessions in the morning and the afternoon too – in 1970 I played 625 record dates!

“Anyway, the producer, Felton Jarvis, called me and said ‘Hey, you can come and play for Elvis, can’t you?’ I said yes, because I thought it would be another great notch on my belt. I’d already worked with Ray Charles and a lot of the big pop stars, so I went down there with my 1965 Precision and an Ampeg B-15 bass amp – and at six PM we were all there, with all the instruments levelled and ready to go.”

Make no mistake, this was a band for the ages. It included pianist David Briggs, multi-instrumentalist Charlie McCoy, drummer Jerry Carrigan and Elvis’s live guitarist James Burton; between them, these musicians had either worked with or would go on to work with Bob Dylan, Paul Simon, Bob Seger, Willie Nelson, Dean Martin, Joan Baez, Nancy Sinatra, B.B. King, Johnny Cash, Dolly Parton, Waylon Jennings, George Harrison, Todd Rundgren, Kris Kristofferson, and Alice Cooper, among many other artists.

Putnam himself has shared a stage or studio with a galaxy of stars, Roy Orbison, Jimmy Buffett, Henry Mancini, Dan Fogelberg, Linda Ronstadt, J. J. Cale, and Tony Joe White among them. And now it was Elvis’s turn.

Again, if you refer to the canon of Presley literature, you’ll find that he is often depicted as a moody, petty, insecure individual at best – and while some of these traits probably emerged at a later point in his life, in 1970 none of this was evident, at least to the Nashville Cats.

As Putnam recalls: “Elvis always came in at eight o’clock precisely – two hours late! – with a big smile on his face, saying ‘Guys, do I have a funny story to tell you’, and he’d talk about himself, sometimes in the third person.

“He’d gather us all around him, because he was a great raconteur – a great storyteller – and because all the seating was around the walls, we all sat on the floor in a circle, even though the tiled floor wasn’t exactly clean. Let me tell you, over the next two hours, until 10 PM, Elvis had us rolling with funny stories.”

He muses: “What’s funny is that after hearing him talk, I’d convinced myself that I knew this guy, because he grew up in Tupelo, Mississippi. I’m talking to you today from Florence, Alabama, which is where I grew up. That’s only 70 miles from Tupelo, and Elvis was just like all the kids I knew when I was growing up, except he was seven years older than me.”

Finally, the producer stepped in to crack the whip. “Felton Jarvis would come up and say ‘Now, Elvis, RCA is expecting us to turn in some tracks this week, and it’s 10 o’clock, and we need to get started’ and Elvis said ‘Okay, Felton – what are we doing first?’

“Felton said ‘Well, we talked about doing an album of country classics, and we want to do a second gospel album, and we might get started on a Christmas album too, and I’ve got seven pop songs’. As he says this, I’m adding this up – and that’s 37 songs, which I thought was impossible to do in five nights. But Elvis said ‘Let’s do this!’ and we went straight into 20 Days And 20 Nights, an old country song.”

The setup was clean and simple, he remembers. “Elvis had them put a long, 20-foot cable on his microphone so he could walk over and stand about eight or nine feet in front of us – guitar, bass, drums, and piano. No headphones back then, either. We had to play quietly so his mic wouldn’t pick us up.”

What’s really weird is that he rehearsed his vocal with a demo singer – a guy who sounded like Elvis. It was bizarre. I’d be standing there, and I’d hear Elvis Presley sing with an imitator who’s imitating Elvis Presley

The band was so finely honed, he adds, that recording progressed swiftly. “The Nashville players had special knowledge. They would play us a demo, and I would grab a legal pad and sketch out the chord progression, the bass-line and any prevalent syncopation. I would draw five lines and sketch it in. We would literally hear a song one time and be ready to play it, based on the arrangement we’d just heard.”

Elvis himself matched their prowess, recalls Putnam, although the King was taken aback by how fast the band worked.

“He was so quick and so good,” he says. “Elvis was a quick study, I have to tell you; he’d only go through a song two or three times, and he had great ears. He’d turn to us and say ‘Do you guys have that? What key was it?’ and Briggs would say ‘That was E flat’.

“Elvis would say ‘Can you move it up?’ and we’d go up to E. ‘A little higher?’ so we went to F. Carrigan would count it off, and the band would play the song flawlessly. Elvis would look at us, like ‘How do you do that?’ because he was used to spending a lot of time on songs, because he had to learn it by rote.

I did 120 tracks with Elvis, and he never, ever changed a note

“What’s really weird is that he rehearsed his vocal with a demo singer – a guy who sounded like Elvis. Haha! It was bizarre. I’d be standing there, and I’d hear Elvis Presley sing with an imitator who’s imitating Elvis Presley. I should have asked him why he did that.

“But he wasn’t interested in working up to a performance, in other words starting gradually on take one and building up to take three or four. No, he was full-on right from the start. We would run the song once for the engineer, and then record it with vocals. He’d be like ‘Let’s get it in the first take’ and start breathing like an athlete. We played to his dynamic. He was almost conducting us with his body language, and I think that’s the reason those records have such a great feel.”

Did he give Putnam any feedback on the bass parts? “No he did not, and that really bothered me on the first night, so when I found myself standing next to him in the control room I said, ‘Hey Elvis, are the bass parts sounding good to you?’ He said ‘Oh, Putt, they sound great!’ and slapped me on the back. Over the next seven years, I did 120 tracks with Elvis, and he never, ever changed a note.”

Elvis dabbled in bass himself every now and then; did he contribute musically to the sessions? “No,” says Putnam. “It’s been said that he picked up an acoustic guitar, but he never did that. He was so centered on his vocal performance. Sometimes he got it on the first take, with a really great vocal, but we realized that we needed another take to get a better rhythm track, so we’d say ‘Elvis, we gotta do it again’ and he’d say ‘Fine’.

“I remember once I was standing beside him while we were listening to a take, and he said ‘Hey Putt, what do you think?’ I said ‘Well, Elvis, could you do one more for me? I’m gonna change my part on the chorus, and David and Chip are gonna make some changes too’. He said ‘Go do it. Felton, we’re doing another one’. One night I walked in there and asked for another take, and he said, ‘Oh, you wanna see me do it again? Let’s go!’”

Elvis was so impressed with the Nashville Cats that he made them an unexpected offer. “He said, ‘Look, you guys have made this so easy for me, I want you to come and be my Las Vegas band. What would it take for you to come and be my band?’ We said ‘Well, could you pay us what we would normally make in a week’s work in Nashville?’ and he said ‘I’ll have Colonel Tom call you’.”

Enter the dread specter of Colonel Tom Parker, the manager who famously made Elvis a star and infamously took 50 percent off the top for doing so. What was he like, we ask?

“Oh, he wouldn’t talk to us lowly musicians!” chuckles Putnam. “I met Colonel Tom when he came to RCA B one night. I remember his assistant walked in, holding a five-gallon jug of Mountain Valley water, because that was the only water the Colonel would imbibe, and behind him, in came the Colonel. He said ‘Elvis, come here!’ They talked for about 20 minutes and then he was gone, without saying goodbye.

“Six weeks later, Charlie McCoy got a phone call from Colonel Tom’s assistant, who said ‘Elvis wants you boys to come out. I understand you want $2,000 a week’. Now, even back in 1970, I could make $100,000 a year in Nashville just by going down to the studio every day, right?

“And this guy goes on, ‘Colonel Tom’s willing to pay $350 a week and $700 to the leader’. Charlie said ‘We’re going to have to pass’. Ha ha! So we never played live with Elvis Presley. In the film Elvis: That’s The Way It Is, you can see the band that did play in Las Vegas listening to the songs we recorded, getting ready to play them on stage.”

When Elvis and the band went their separate ways, Putnam didn’t see him for another two years, by which point the King’s later-life malaise had started to make itself obvious.

“By the time ’73 rolled around, his wife Priscilla had left him,” he recalls. “We were asked to come over to Stax Studios to track, and when he came in, I saw that he had started to gain weight – maybe 15 pounds or so. He was a little pasty-looking, and was wearing this loose-fitting exercise outfit. His demeanour had changed: He wasn’t as much fun.”

He adds, regretfully: “Four years after that, he was gone.” How did Putnam hear of Elvis’s death? “By 1977, I was an established producer. It was a great year for me: Two of my artists had gone triple platinum. Dan Fogelberg had sold three million albums, and Jimmy Buffett had recorded Margaritaville, which went on to sell 40 million copies.

“That summer, I got a phone call from Felton Jarvis, and he said ‘Hey Norbert, could you come and overdub bass on a Presley song?’ I said ‘Just one song?’ ‘Yeah. Elvis was on tour and he decided to go over the piano and sing the Everly Brothers song Unchained Melody. It’s the best vocal he’s done in years, and we got it on multi-track. I want you to add bass to it’.”

During the recording, Putnam asked Jarvis about his old boss’s health. “He said, ‘Well, Putt, he just gained so much weight. Last week I saw him eat a dozen eggs and a pound of bacon for breakfast’. I said ‘You’re kidding?’ and he said ‘The day before that, he binged on banana splits – he had a dozen of them’.”

“I said ‘Is it just obesity that’s the problem?’ because I thought that could be dealt with, but he said ‘No, it’s more than that. Elvis has been pretty depressed lately’. I said ‘Can’t the Colonel or someone do something?’ and he told me that Elvis had been in the hospital several times to get off his medication, but it just hadn’t worked. And I said ‘Well, give him a hug from me’.”

I went into a store and this hippie guy said to the cashier, ‘Did you hear about old Presley?’ The guy said ‘No?’ and the hippie said ‘He checked out’. I ran to my car... I could not believe it. I sat there and cried

He continues: “Two months later I was on vacation in Hawaii, and I was in my car with the radio on, and they were playing Elvis tracks over and over. That made me smile, because American radio did not play Elvis Presley’s songs after 1970.

“We had payola back then, and the record company admitted to me that they stopped paying payola after 1970. I said ‘Why?’ and they said ‘Because we had this new guy from England called David Bowie, who was going to be the new Elvis’.

“I went into a store to buy some items, and this hippie guy said to the cashier, ‘Did you hear about old Presley?’ The guy said ‘No?’ and the hippie said ‘He checked out’. I ran to my car and turned on the radio, and they were announcing it. I could not believe it. I thought, ‘They let him die’, and I sat there and cried.”

Fifty years since those sessions, how does Putnam remember Elvis? “I remember him for how much fun he was, back in 1970. We were young, we were all playing great, and we had a great time. The reason we got 35 sides in five days was because he was having so much fun. He was just the absolute best, and that’s how I’ll always think of him.”

Joel McIver was the Editor of Bass Player magazine from 2018 to 2022, having spent six years before that editing Bass Guitar magazine. A journalist with 25 years' experience in the music field, he's also the author of 35 books, a couple of bestsellers among them. He regularly appears on podcasts, radio and TV.

“When I first heard his voice in my headphones, there was that moment of, ‘My God! I’m recording with David Bowie!’” Bassist Tim Lefebvre on the making of David Bowie's Lazarus

“One of the guys said, ‘Joni, there’s this weird bass player in Florida, you’d probably like him’”: How Joni Mitchell formed an unlikely partnership with Jaco Pastorius