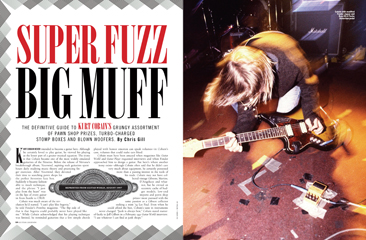

Nirvana: Super Fuzz Big Muff

The definitive guide to Kurt Cobain’s grungy assortment of pawn shop prizes, turbo- charged stomp boxes and blown woofers.

Kurt Cobain never intended to become a guitar hero. Although he certainly loved to play guitar, he viewed his playing as the lesser part of a greater musical equation. The irony is that Cobain became one of the most widely emulated guitarists of the Nineties. Before the release of Nirvana’s breakthrough album, Nevermind, aspiring rock guitarists spent hours daily studying music theory and practicing finger exercises. After Nevermind, they devoted their time to searching pawn shops for the perfect Seventies fuzz box. Suddenly it became fashionable to mock technique, and the phrase “I just play from the heart” was on the lips of every guitarist from Seattle to CBGB.

Cobain was much aware of the revolution he’d started. “I can’t play like Segovia,” he told Fender’s Frontline magazine. “The flip side of that is that Segovia could probably never have played like me.” While Cobain acknowledged that his playing technique was limited, he reminded guitarists that a few simple chords played with honest emotion can speak volumes—in Cobain’s case, volumes that could make ears bleed.

Cobain must have been amused when magazines like Guitar World and Guitar Player requested interviews and when Fender approached him to design a guitar. But here’s where another irony exists—although Cobain often said that he didn’t care very much about equipment, he certainly possessed more than a passing interest in the tools of his trade. Cobain may not have collected vintage Gibsons, Martins, D’Angelicos and whatnot, but he owned an eccentric cache of budget models, low-end imports and pawn shop prizes—most pursued with the same passion as a Gibson collector seeking a mint ’59 Les Paul. Even when he could afford the best, Cobain’s taste in instruments never changed. “Junk is always best,” Cobain stated matter-of- factly to Jeff Gilbert in a February 1992 Guitar World interview. “I use whatever I can find at junk shops.”

As increasing numbers of aspiring musicians made Cobain their mentor, they began to wonder how he created the wide array of sometimes angry, sometimes ethereal tones that poured from his battered guitars and over-powered amps. The uninitiated speculated that Cobain used special processors and studio trickery to obtain his sound. As Cobain’s influence spread across the world, so did the rumors about what he played.

Guitar World feels that the time has come for the truth about Cobain’s equipment to be revealed. To solve these mysteries and dispel the rumors, we contacted the most reliable sources available—the dealers who sold him his equipment, the engineers and producers who worked with him in the studio and the technicians who looked after his gear on the road. Cobain probably would have laughed at the idea of a magazine scrutinizing the minute details of his gear. “I’ve never considered musical equipment very sacred,” he once said. But for the thousands of guitarists who consider Cobain’s music sacred, it’s important to understand what he played and why he played it.

SCENTLESS APPRENTICE —COBAIN’S VIRGIN MUSICAL YEARS

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Kurt Donald Cobain was born in Aberdeen, Washington, on February 20, 1967. Growing up in the company of several musicians—his uncle Chuck played in a rock band and his aunt Mary played guitar—Cobain showed an early interest in music. As a youngster, he would often bang at the strings on a plastic toy guitar while singing along with his favorite Beatles records. Cobain’s aunt Mary encouraged his musical development and attempted to teach him guitar when he was seven, but he had difficulty learning.

Expressing desires of becoming “John Lennon playing drums” when he grew up, Cobain started taking drum lessons in the third grade. He switched to guitar in 1981 when his uncle Chuck gave him a used electric guitar and a small 10-watt amp for his 14th birthday. “As soon as I got my guitar, I just became so obsessed with it,” Cobain told Michael Azerrad. “I don’t think it was even a Harmony. I think it was a Sears.” Cobain took guitar lessons for less than a month—just long enough to learn how to play AC/DC’s “Back in Black.” Those three chords served him well when he began writing his own songs shortly thereafter.

Cobain soon set his sights on forming a band. One day, a couple of friends invited him to jam in an abandoned meat locker that they used as a practice space. Afterwards, Cobain foolishly left his guitar in the locker and was subsequently unable to return and get it back. When he finally made it back to the rehearsal space a few months later, he found his guitar in pieces. He salvaged the neck, hardware and electronics and made a new body for the guitar in wood shop, but Cobain lacked the skills to make the restored instrument intonate properly. Later he acquired a replacement, but details about the guitar are unknown.

When Cobain was 17, his mother married Pat O’Connor, whose ensuing infidelity led to a situation that greatly facilitated Cobain’s acquisition of musical gear. After Cobain’s mother learned that Pat was cheating on her, she dumped his rifle and gun collection in the river. Cobain observed his mother’s antics and later encouraged some of the neighborhood kids to fish his stepdad’s weapons out of the river. Cobain sold the guns and bought a used Peavey Vintage amplifier with two 12-inch speakers with the proceeds. Once the Peavey became a member of the Cobain household, Aberdeen rarely knew a peaceful evening.

In early 1985, Cobain moved in with his natural father who discouraged his son’s musical pursuits and convinced him to pawn his guitar. After about a week, Cobain got his guitar out of hock and moved out. He almost lost the guitar again when he loaned it to a drug dealer, but managed to repossess it a few months later. With this unknown guitar and the Peavey amp in hand, Cobain formed his first band, Fecal Matter, in late 1985.

The Peavey amp disappeared sometime between early 1986 and late 1987. Krist Novoselic remembers that Cobain gave the amp to him for about a week, in what apparently was a friendly attempt to get him to join Fecal Matter. Novoselic declined on both offers. The amp disappeared sometime after that.

By late 1987 Novoselic finally agreed to form a band with Cobain and drummer Aaron Burckhard, which they called Skid Row (no relation to the Sebastian Bach– fronted metal outfit of the same name). Photos from this era show Cobain playing a right-hand model sunburst Univox Hi-Flyer flipped over and strung for left-handed playing. According to Azerrad, Cobain’s amp during this period was a tiny Fender Champ. Also around this time, Cobain acquired a Univox Superfuzz but it was stolen from his rehearsal space.

The band’s name changed frequently, from Fecal Matter to such similarly choice monikers as Ted Ed Fred, Pen Cap Chew, Throat Oyster, Windowpane and Bliss. Eventually they settled on Nirvana. When Burckhard proved too unreliable, Cobain and Novoselic kicked him out of the band and enlisted drummer Dale Crover, who they temporarily stole from the Melvins. Three weeks later, on January 23, 1988, Nirvana recorded its first studio demo at Reciprocal Studio with Jack Endino— whose early production/engineering/mixing credits include Soundgarden, Green River, Tad and Mudhoney—behind the board.

BLOND AMBITION —THE BLEACH YEARS

Jack Endino was not supposed to work on Nirvana’s demo session, but because he was impressed by Crover’s playing with the Melvins, he insisted on doing the recording. The band’s working relationship with Endino proved to be exceptionally fortuitous. A few months after working with Nirvana for the first time, Endino played the band’s demo tape for Jonathan Poneman of Sub Pop Records, who signed the band to the label. Three of the songs that Nirvana recorded during that session ended up on Bleach, the band’s first album.

“They didn’t have a whole lot of equipment,” says Endino. “In the early days, Kurt used a Randall amplifier head. It may not have even been a tube model— I think it was solid-state. I don’t recall what the speakers were.”

The band liked working with Endino, and they returned to Reciprocal Studios several times during the year to record more songs, although Chad Channing replaced Crover on drums. Nirvana signed a contract with Sub Pop, and in late December 1988, they entered Reciprocal Studios to record Bleach. The album was recorded in three days at a cost of $606.16, although five tracks from earlier sessions were included on the final album. Most of the remaining songs from the various Reciprocal sessions were released several years later on Incesticide.

“When they recorded Bleach, the Randall was in the shop so they borrowed my amp, which was a Sixties Fender Twin,” Endino recalls. “I’m a tube nut, so everything was tweaked and up to spec on that amp, but it didn’t have speakers because I had fried them. Kurt brought in a little closedback 2x12 cabinet with two Celestions, most likely 70-watt models. He was using a little orange Boss DS-1 distortion pedal and these Univox guitars [Hi-Flyers] that looked like Mosrites. The pickups were stock. I ended up getting one of those pickups from him once, because he was smashing those guitars all the time. I said, ‘You must have some extra pickups,’ and he said, ‘Oh yeah. Here’s one.’ It was in two pieces. I was able to stick the wires together and use it. It’s not the greatest sounding pickup in the world, but it seemed to work for him.”

While playing at a Halloween party on October 30, 1988, in a dormitory at Washington’s Evergreen State College, Cobain smashed a guitar—a sunburst Univox Hi-Flyer—for the first time. According to Cobain, his destructive habit started due to his frustration with Channing’s drumming. “I got so pissed off at Chad that I’d jump into the drum set, then smash my guitar,” Cobain told Azerrad. “That really is how the instrument smashing came about.”

In 1989, Nirvana went on its first American tour. According to Earnie Bailey, a Seattle guitar repairman who was friends with Novoselic and who often worked as a technician for the band, Cobain’s live rig during this period was a red Epiphone ET270, a solid-state Randall amp head, a BFI Bullfrog 4x12 cabinet and a Boss DS-1 distortion. When his guitar was destroyed beyond repair, Cobain would look for cheap replacements in pawn shops or have Sub Pop ship him guitars via Federal Express. Sometimes, fans would sell Cobain a guitar, which he would later destroy with extreme gusto.

“I heard stories about Kurt’s guitar destruction from the Sub Pop people early on,” says Endino. “When he was out on the road he’d call them up and say, ‘I don’t know what got into me, but I just smashed up my guitar.’ I don’t think he was planning on smashing guitars from day one. It was just something he did. The poor Sub Pop people would call all the pawn shops up and down the coast, looking for Univox guitars.”

Between tours, Cobain often bought equipment from Guitar Maniacs in Tacoma, Washington, and Danny’s Music in Everett, Washington. According to Rick King, owner of Guitar Maniacs, Cobain “bought a whole bunch of Univox Hi- Flyers—both the P-90 version and ones with humbuckers. Those pickups have huge output and are completely over the top. He broke a lot of those guitars. We sold him several of them for an average of $100 each over the course of five years.”

Although humbucker-equipped Univox Hi-Flyers apparently were Cobain’s favorite guitars in the pre-Nevermind days, he often appeared onstage with other models, including a blue Gibson SG and a sunburst left-handed Greco Mustang copy that he bought from Guitar Maniacs. The Mustang copy allegedly was destroyed on July 9, 1989, at a gig in Pennsylvania, but it may have experienced some form of reincarnation since a similar guitar is seen in photos of Nirvana at a gig at Seattle’s HUB East Ballroom on January 6, 1990.

Cobain purchased what probably was his first acoustic guitar, a Stella 12-string, for $31.21 on October 12, 1989. He brought the Stella to Smart Studios in Wisconsin to record some demos with Butch Vig in April 1990. The guitar wasn’t exactly a studio musician’s dream. “It barely stays in tune,” Cobain told Jeff Gilbert in a February 1992 Guitar World interview. “I have to use duct tape to hold the tuning keys in place.” At some point in the Stella’s history, the steel strings had been replaced with six nylon strings, only five of which were intact during the session. However, the guitar sounded good enough to Vig, who recorded Cobain playing a solo acoustic version of “Polly” on that guitar. That track can be heard on Nevermind.

Cobain didn’t seem to be exceptionally particular about what equipment he was playing through. Perhaps the best example of this was when Nirvana cut the “Sliver” single. “I was in the studio working on a record with Tad,” says Jack Endino. “Nirvana wanted to come in and record the song during Tad’s dinner break, so they just used Tad’s equipment.” Anyone familiar with Tad’s eating habits knows that Nirvana probably could have recorded an entire album during that break.

The one thing that Cobain was particular about was his effect pedals. Sometime in 1990, he bought an Electro-Harmonix Small Clone from Guitar Maniacs, and it remained a favorite and essential part of his setup to the end of his life. On January 1, 1991, Cobain used the Small Clone to record “Aneurysm,” which later was issued as the b-side to the “Smells Like Teen Spirit” single.

BREEDING GROUND—THE RECORDING OF NEVERMIND

Prior to formally signing with Geffen Records on April 30, 1991, Nirvana received a $287,000 advance for the recording of Nevermind. The advance was somewhat meager, but it gave the band some freedom in choosing equipment. However, Cobain didn’t exactly go wild with his spending.

“I sold Kurt a bunch of guitars and effects for the Nevermind album,” says Rick King. “When they got signed to Geffen and started getting money, Kurt was still very frugal. He bought some Japanese left-handed Strats and had humbuckers installed in the Strats’ lead position. He didn’t spend very much money on guitars.”

Apparently Cobain developed a taste for Fender guitars just prior to recording Nevermind. “I like guitars in the Fender style because they have skinny necks,” said Cobain in a late 1991 interview. “I’ve resorted to Japanese-made Fender Stratocasters because they’re the most available left-handed guitars.” During this period, he also acquired a left-handed ’65 Jaguar that had a DiMarzio Super Distortion humbucker in the bridge position and a DiMarzio PAF in the neck position in place of the guitar’s stock single-coil pickups. These modifications were made before Cobain purchased the guitar. Cobain also bought a left-handed, Lake Placid Blue ’69 Fender Competition Mustang around then.

“Out of all the guitars in the whole world, the Fender Mustang is my favorite,” Cobain told GW. “They’re cheap and totally inefficient, and they sound like crap and are very small. They also don’t stay in tune, and when you want to raise the string action on the fretboard, you have to loosen all the strings and completely remove the bridge. You have to turn these little screws with your fingers and hope that you’ve estimated it right. If you screw up, you have to repeat the process over and over until you get it right. Whoever invented that guitar was a dork. I guess I’m calling Leo Fender, the dead guy, a dork.” To overcome these tuning problems, Cobain had his ’69 Mustang fitted with a Gotoh Tune-O-Matic bridge, a modification that was routinely performed on the Mustangs he subsequently acquired.

Some claim that Cobain’s preference for low-end guitars was a punk statement, but he insisted that it was a matter of necessity. “I don’t favor them,” Cobain told Guitar World in ’92. “I can afford them. I’m left-handed and it’s not very easy to find reasonably priced, high-quality left-handed guitars.”

Before entering the studio, Cobain purchased a rack rig consisting of a Mesa/Boogie Studio preamp, a Crown power amp and a variety of Marshall 4x12 cabinets. “I can never find an amp that’s powerful enough,” Cobain told GW. “And I don’t want to deal with hauling 10 Marshall heads. I’m lazy—I like to have it all in one package. For a preamp I have a Mesa/Boogie, and I turn all the midrange up.” Cobain brought this rig along with his Mustang, Jaguar, a Japanese Strat and his Boss DS-1 and Electro-Harmonix Small Clone pedals to Sound City Studios in Van Nuys, California, where the band recorded Nevermind with Butch Vig.

“Kurt had a Mesa/Boogie, but we also used a Fender Bassman a lot and a Vox AC30 on Nevermind,” Vig recalls. “I prefer getting the amp to sound distorted instead of using special effects or pedals, which lose body and the fullness of the bottom end, even though you can get nice distortion with some of them. If you get a good-sounding amp, that’s 90 percent of it.”

But even though Vig wasn’t the biggest fan of effect pedals, he allowed Cobain to use a few on the album, especially since the guitarist felt that the DS-1 was the main factor in his tone. Cobain also used the Small Clone liberally. “That’s making the watery guitar sound you hear on the pre-chorus build-up of ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ and also ‘Come as You Are,’ ” says Vig. “We used an Electro- Harmonix Big Muff fuzz box through a Fender Bassman on ‘Lithium’ to get that thumpier, darker sound.”

Cobain’s pawnshop Stella, which he had played at the sessions held at Vig’s Smart Studios a year earlier, was used again for “Something in the Way.” Vig recorded the performance while Cobain sat on a couch in the control room.

Against Vig’s wishes, Cobain plugged his guitar direct into the board for “Territorial Pissings.” During the recording of “Lithium,” Cobain instigated the noise jam that became the “hidden” track “Endless, Nameless.” (This track does not appear on the first 50,000 copies of the CD.) Toward the end of the track, Cobain can be heard smashing his Japanese Stratocaster.

LOUNGE ACT—THE NEVERMIND TOUR

After Nirvana finished basic tracking, they opened for Dinosaur Jr on brief tours in the U.S. and Europe. The Nevermind tour started in Toronto on September 20, 1991, a few days before the album was released. Nick Close, Cobain’s guitar tech from September 1991 until March 1992, recalls that Cobain’s rig was basically the same as the one used to record Nevermind—the Mesa/Boogie Studio preamp, a Crown power amp, a Boss DS-1 and the Small Clone. Initially, only a handful of guitars were taken along on tour—the ’65 Jaguar, the ’69 Mustang and a left-handed Japanese Strat. Later, Cobain picked up a sunburst Telecaster that he painted sky blue and scratched off some of the paint in the shape of a heart and the word “Courtney.”

“When I was working for them, the money hadn’t started coming in,” says Close. “There was a lot of equipment out there that would have made Kurt a lot happier onstage, but they didn’t get tried because of time and money. And Kurt wasn’t much of a gearhead. He didn’t want to sit down and talk about what could be done.”

Close says that the Crown power amp was a particular source of frustration. “It never worked very well for us,” he says. “The output on that Studio preamp was very hot. Because of that, the Crown would blow up a lot, and I was always having to get it repaired.” Frustrated with the Crown, Close eventually ordered two Crest 4801 power amps. Finally they had found an amp that could withstand the onslaught of abuse. Earnie Bailey referred to the Crest as “the amp that wouldn’t die,” and they remained in Cobain’s rig until the end.

Due to the constant thrashing endured by the equipment, Close was constantly looking for replacements. “Everybody had the exact number of things needed to make the show happen,” says Close. “If anything broke, we were screwed. I was trying to move them in the direction of having extra cords and pedals. Kurt started out with the Boss DS-1, and I was always looking for a backup. One time the Crown amp blew up and took the speakers with it. We were in a music store to buy some Marshall cabinets, and I saw a DS-2 there and bought it. Kurt didn’t seem to be too happy with it at first, but he put it in his rig after he broke his DS-1 in Hawaii. [A performance photo on the insert of In Utero clearly shows Cobain’s DS-2 and Small Clone.]”

Kurt’s guitars constantly needed repairs as well. Generally, the Strat received most of the abuse. “Lately I’ve been using a Strat live because I don’t want to ruin my Mustang yet,” Cobain told GW. “I like to use Japanese Strats because they’re a bit cheaper, and the frets are smaller than the American version’s.”

Close acquired a small stash of replacement necks from Fender, but soon he was replacing necks on the Strat every night. Frustrated, he visited luthier Danny Ferrington when the band arrived in Los Angeles in late December and asked him to build some replacement necks for Cobain’s guitars. Instead, Ferrington offered to build a guitar for Cobain. “Danny was in the middle of doing his book [Ferrington Guitars, Harper Collins], and he took the whole project and ran with it,” says Close. “I was in awe of Ferrington. I don’t know whether Kurt cared if someone was making him a guitar, but he seemed to read my enthusiasm.”

Cobain drew a picture of what he wanted and faxed it to Ferrington from Melbourne, Australia. Ferrington delivered the finished guitar, essentially a left-handed Mustang with a Tune-O-Matic bridge, heart-shaped fingerboard inlays, a Strat-style angled output jack and a humbucker and two single-coil Bartolini pickups, to Cobain in the summer of ’92. Perhaps the most expensive guitar that Cobain ever owned, the Ferrington didn’t see much action on the road and eventually was kept at home.

When money started coming in, Cobain bought more guitars but he retained his taste for low-budget gear. Perhaps Cobain’s most “extravagant” purchase during this time was a mid-Sixties Fender Electric XII, with which he wrote “Serve the Servants.” This guitar was subsequently damaged when some sewage backed up into the bathtub where Kurt had it stored. Cobain allegedly left the guitar in the tub to fool potential burglars. He also returned to Guitar Maniacs, where he bought an Electro-Harmonix Echo Flanger for $99. This pedal later played a significant role in the recording of In Utero.

NO APOLOGIES—COBAIN RECLAIMS HIS PUNK ROOTS ON IN UTERO

In late February 1993, Cobain, Novoselic and Grohl traveled to Pachyderm Studios, in Minnesota, to record In Utero with Steve Albini. This time, however, Cobain left his live rig behind at home.

“For In Utero, Kurt primarily used his Jaguar and a Twin Reverb,” Earnie Bailey said in the March 1995 issue of Guitar World. “Effects consisted of a Boss DS-2 distortion, a Small Clone and an Electro- Harmonix Poly Chorus.” Bailey loaned the Poly Chorus to Cobain because his Echo Flanger was acting up. (The Echo Flanger, Poly Chorus and Poly Flanger all have the same circuitry but slightly different cosmetics.) The Twin Reverb was a 1982 135- watt blackface model that Cobain picked up sometime before the sessions started. Originally, it had only two of its four 6L6 output tubes in place, so it was running at half power. Cobain really liked the sound that way and told Bailey to leave the amp alone. As a prank, Bailey placed four matched tubes in the amp prior to rehearsals for In Utero. Cobain noticed the difference immediately, remarking that the amp sounded better than ever.

Cobain also brought along his trusty Stella acoustic, which had been equipped with new tuners and strings, courtesy of Bailey. The Stella was used on three songs—“Dumb,” “Pennyroyal Tea” and “All Apologies.” Bailey also recalls sending a sunburst lefty Ibanez Les Paul Custom copy to the studio, but he’s not certain whether the guitar was used or not.

Some of the most impressive sounds on In Utero were created with the Echo Flanger. Cobain dialed in a variety of effects on the unit, including the abrasive flanging effect on “Scentless Apprentice,” the bizarre, wobbling vibrato sounds on “Radio Friendly Unit Shifter” and the deep chorus tones on “Heart Shaped Box.”

In typical indie rock fashion, the basic tracks for In Utero were completed in two weeks. The total cost of recording was $124,000: $24,000 for studio bills and $100,000 for Albini.

In February 1993, right before In Utero was recorded, Cobain collaborated with Fender on the design of what later became known as the Jag-Stang. According to Mark Wittenberg, who was director of artist relations for Fender until he died of a brain aneurysm on February 14, 1995, “We were contacted and told that Kurt had an idea for a guitar. His favorite guitar was a Mustang, but there were things about the lines of the Jaguar that he really liked, too.” Wittenberg and builder Larry Brooks met Cobain at his apartment in Hollywood, where they discussed his plans for a guitar that combined the aesthetics of a Jaguar and a Mustang, hence the name “Jag-Stang.”

The guitar Cobain envisioned featured a Mustang’s neck and upper bout and a Jaguar’s lower bout. He later sent Fender an illustration and specified a small, pre-CBS style headstock, double-coil Duncan Hot Rail bridge pickup, a Mustang single-coil neck pickup and several suggestions for the body shape. Cobain also sent Fender the neck of his favorite Mustang for them to copy. A couple of different versions of the body were sent to Cobain for his approval, and once Fender came up with a shape he liked, the prototype was completed.

The prototype had a large, CBS-style headstock, a DiMarzio H-3 bridge humbucker, a Fender Texas Special neck singlecoil and stock Mustang hardware. According to Jim Vincent, Cobain’s guitar tech on the In Utero tour, “Kurt wasn’t really all that happy when he got the first Jag-Stang. He liked his Mustangs much better, even the new ones. For the month he had it, he hated it and wouldn’t play it because there was no contour—it’s as thick as a Tele—and it was kind of misbalanced. It was really tough to set up. Earnie immediately swapped out the pickups. Right when we got it, he routed it out and put a Duncan JB humbucker in the bridge.” Bailey also installed a Tune-O-Matic bridge on the guitar. Eventually, Cobain grew comfortable enough with the Jag-Stang to use it on rare occasions for an entire show.

FROM THE CRADLE TO THE GRAVE—THE IN UTERO TOUR AND THE FINAL DAYS

In Utero was released September 21, 1993, almost exactly two years after Nevermind. Nirvana had performed only a handful of live shows during 1993, but in October of that year the band set out on its biggest tour ever. By now Nirvana was headlining arena shows and playing to increasingly larger audiences. However, Cobain’s stage rig remained almost the same as before, probably because it was so excruciatingly loud. The only changes were the addition of the Electro- Harmonix Echo Flanger (which alternated duty with Bailey’s Poly Chorus) and a Tech 21 SansAmp. (A good live photo showing all of Kurt’s pedals is on the cover of From the Muddy Banks of the Wishkah). “His signal chain went as follows: guitar- Boss DS-2-SansAmp-Poly Chorus or Echo Flanger (whichever worked that day)- Small Clone-amp,” says Bailey.

According to Vincent, the SansAmp was the main source of Cobain’s distorted tone. “He also used the DS-2, but that was mainly used on the acoustic guitar for ‘The Man Who Sold the World,’ ” says Vincent. “Occasionally, he’d use both pedals at once. Kurt’s settings on the SansAmp’s DIP switches were, from left to right, three up, three down, two up, and all of the knobs were turned all of the way up, except for the high control, which was at about 12 o’clock.” Vincent does not remember where SansAmp’s three-position switch was set, but he thinks it was on the Normal (center) setting.

Vincent says that Cobain would take care of the settings on all of his pedals, sometimes changing them between songs. “He knew all the sweet spots really well,” says Vincent. To help get the sounds he wanted more quickly, Cobain marked the different settings on the Echo Flanger and Poly Chorus pedals with nail polish.

Before the band went on tour, Fender sent Cobain one Fiesta Red and three Sonic Blue Mustangs and a variety of Mexican Stratocasters fitted with humbuckers. Bailey installed Gotoh Tune-OMatic bridges and Seymour Duncan JB humbuckers on the Mustangs, cut the nuts for heavier strings, shimmed the necks, flipped the tailpieces so the strings could be inserted without going under the tailpiece and blocked the tailpieces so the tremolo bar wouldn’t work.

“One of the blue Mustangs never came out of the box and was unmodified because we were waiting until the other ones were broken,” says Vincent. “The blue Competition Mustang from Nevermind was in storage because Kurt really liked that guitar.” However Cobain had dusted off a few of his Univox Hi-Flyers, and these showed up onstage occasionally.

The Mexican Strats were mainly there for sacrifice to the distortion god at the end of the set. “We had a predetermined black Mexican Strat that we would give to Kurt to smash,” says Vincent. “Sometimes he’d want one of the Mustangs, but we wouldn’t give him one. Then he’d go, ‘Yeah, all right. I don’t want to break that guitar because it feels really good.’ ”

Photos taken at various shows give the impression that Cobain had an endless supply of Mustangs and Stratocasters, but Vincent says this is misleading. Kurt’s techs were constantly recycling parts from the guitars that he destroyed, and they often pieced instruments together. “Some of these Nirvana gear web sites list a million guitars,” says Vincent. “According to Earnie, most of those guitars are the same, only the pickguard, pickups or neck might have been changed.”

After completing In Utero, Cobain became more interested in acoustic instruments, and he looked for a replacement for his Stella. Before the tour, Cobain bought an early Sixties right-hand Epiphone Texan, and Bailey replaced the guitar’s adjustable bridge with a left-hand bridge and a standard saddle. In the fall of ’93, he bought a Martin D-18E electric- acoustic flat-top from Voltage Guitar in Los Angeles. An extremely rare late- Fifties model (only 302 were produced), the D-18E is essentially a D-18 with two DeArmond pickups installed at the Martin factory. “Unfortunately, the instrument’s pickups were designed with nickel strings in mind, so hearing it with bronze-wound strings was pretty disappointing,” Bailey said in the March ’95 GW. “Our solution was to attach yet another pickup—a Bartolini model 3AV—to the top.” This guitar became his main acoustic guitar for the In Utero tour and for Nirvana’s appearance on MTV’s Unplugged.

Taped on November 18, 1993, and aired about a month later, Nirvana’s Unplugged performance proved to be the ultimate coda to Cobain’s musical career. Cobain insisted on bringing the Martin to the taping, even though Bailey thought the Epiphone sounded much better. The D-18E was connected to a Small Clone and DS-2 (in a photo on the CD insert, the DS-2 can be seen slightly above the DGC logo) and run into a Twin Reverb, which was used only as a monitor. The Echo Flanger and Poly Chorus were also brought to the rehearsal, but they were not used on the taping because they created too much 60-cycle hum.

In early ’94, Fender sent Cobain a sunburst Telecaster Custom. Bailey installed a Duncan JB in the bridge position and a Gibson PAF in the neck position. According to Bailey, this was Cobain’s new favorite guitar. He used the guitar for a March 1994, recording session in his basement with Pat Smear and Hole’s Eric Erlandson. This may be the last guitar that Cobain played before he took his own life.

“The original Jordan Boss Tone was probably used by four out of five garage bands in the late ’60s”: Unpacking the gnarly magic of the Jordan Boss Tone – an actual guitar plug-in that delivers Dan Auerbach-approved fuzz

“This is a powerhouse of a stompbox that manages to keep things simple while offering endless inspiration”: Strymon EC-1 Single Head dTape Echo pedal review