Nirvana: The Final Scream

Originally printed in Guitar World, November 2008

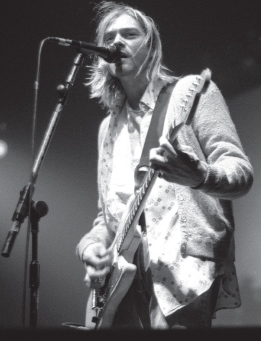

March 1, 1994 - Munich, Germany

If there was a beginning of the end of Kurt Cobain’s short life, that final chapter most certainly began in February 1994. Nirvana were touring Europe, promoting their 1993 album, In Utero, and trying to plan the rest of their tour schedule for the summer. Though Kurt had reluctantly agreed to do the European leg of the tour, he began the trip with the motivation that he was promoting a record he was proud of. The first few shows of the tour had been terrific, even if Kurt was already complaining of a sore throat. Problems with his throat necessitated three visits to doctors in the first week. In truth, the larger health crisis was that he had difficulty finding drugs in Europe, and that had soured his mood and affected his health. Cobain’s withdrawal was bad enough that he was forced to take prescription drugs to help him cope.

But in Paris on February 13, Cobain’s typical melancholy mood turned into something that in retrospect was a harbinger of doom. The band agreed to do a photo session on its off day with a photographer they had known for years, Youri Lenquette. Cobain considered Lenquette a friend, which is why he had agreed to the session at a point in his career where he rarely did promotional work. It was no surprise that Kurt refused to smile during the session, but when he found a BB gun in Lenquette’s studio, the gun turned into the focal point of the sitting. Lenquette later recalled trying to convince Kurt to put the gun down, but Kurt insisted that it be included in the photos. The gun looked remarkably like a firearm, but it was merely something Lenquette kept in his studio as a prop and as a sort of joke.

To the photographer and the other two members of Nirvana, Cobain’s fascination with the pistol was anything but humorous. He kept playing with the gun, put it to his temple and mimed pulling the trigger. He completed the act by pretending his head was reacting to the bullet. It was suggested again that Kurt put the gun down, but he ignored that plea and insisted that Lenquette take a photograph. For Lenquette it was a difficult situation: he had the most famous rock star in the world posing outrageously, but the poses seemed in bad taste. Still, the photographer kept shooting. In one picture taken that day, Kurt inserted the barrel of the pistol into his mouth. The pictures were widely published after his death.

That Kurt Cobain would pose with a gun in his mouth—in front of a photographer whosold pictures to news agencies worldwide—is indicative of how far things had gone downhill. Early in his career, Cobain was a master at controlling and manipulating his image, even directing photographers to shoot him from certain angles. Cobain always vamped it up for photo sessions and had been photographed with guns before, but the grotesque nature of the Paris photos suggested something beyond simple punk rock cynicism—it reflected desperation, nihilism and a larger death wish that was playing itself out in every aspect of Kurt’s life. He simply didn’t care anymore about anything: not his health, band or the public image he had once valued so dearly.

Kurt didn’t pull any real triggers that day in Paris, but as the tour wound through Europe, he began an almost daily ritual of visiting a doctor in whatever town the band was passing through. He complained of stomach problems, back problems and throat pain, but most of his ailments were due to drug withdrawal. Much of Europe viewed drug addiction compassionately as a sickness, in contrast to the United States, where it was considered a moral failing. Many European doctors would prescribe opiates in pill form to help addicts suffering from withdrawals. Still, finding a physician so inclined was a hit-or-miss proposition, particularly in cities where Nirvana had never toured before. In Barcelona, Kurt visited one doctor, and when that failed to produce the desired results, he visited another later in the same day. In Paris, he visited one physician twice; the next day, in Rennes, he saw yet another.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

How many of Kurt’s physical problems were related to his addiction and how may were separate issues could never be determined. By that point in his life, it was all intertwined. When he took the more illicit route and bought drugs on the streets, he couldn’t risk taking them across a border, so he was able to use only enough to get over the day’s withdrawal. It wasn’t a matter of seeking euphoria—drugs had long ago failed to give Kurt a high. It was simply a matter of staving off vomiting, fever and the shakes.

On February 20, on a day that saw the band traveleing from Switzerland to Modena, Italy, Kurt turned 27. There was little celebration on the tour bus. His manager, John Silva, gave Kurt a carton of cigarettes as a present. Cobain joked to the crew that his manager was trying to kill him, but considering his own health, cigarettes were hardly his biggest worry. February 24 was Kurt and Courtney’s second anniversary, but they were not together. Kurt put off any celebrating—he had planned that for later in the month when they were together—and played a show in Milan, which was issued as a bootleg. It may have represented the last decent Nirvana show, as the group tore through 22 songs over 90 minutes. Kurt was clearly struggling with his voice, but the punk part of Nirvana’s sound was still strong, and the crowd loved them.

By the next night, also in Milan, Kurt’s dark mood became increasingly desperate. He met with Krist Novoselic and told him that he needed to quit the tour. “He gave me some bullshit absurd reason for why he wanted to blow it off,” Novoselic recalled. Though Kurt’s voice had been his main physical complaint in Europe, he now added the familiar complaint of stomach pains to his litany of medical conditions. Krist was having none of it; he reminded Kurt of the huge financial obligation the band would have if they called the tour off. Kurt agreed to continue with the tour, if only to make it through the next date which would take them to Slovenia, where Novoselic had relatives.

There were neither street drugs nor easily swayed physicians to be found in Slovenia, and while Novoselic and Grohl explored the country, Kurt stayed in his room for three days, bouncing off the walls. He was miserable, and he continued to talk of ending the tour. While in Slovenia, Novoselic was reading One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, by Alexander Solzhenitsyn, describing a prisoner’s life in a Soviet prison camp. Kurt asked Krist about the plot of the book, and when he heard Solzhenitsyn’s description of the camp, he remarked, “God, and [Denisovich] wants to live! Why would you try to live?”

On March 1, 1994, Nirvana rolled into Germany, where they had three consecutive shows scheduled before a one-week break. The attitude among the crew and band was to tough it out for these shows and then enjoy the upcoming time off to vacation and regroup. While in Slovenia, Kurt had called a band meeting and again said he wanted to cancel the rest of the tour. He’d been informed that the band did not have cancellation insurance, so to pull the plug at this point would result in a huge financial penalty. “So, if somebody died, we’d still have to do the shows?” Kurt asked. He was informed that death was the only acceptable reason for a cancellation.

The March 1 Munich show was held in Terminal Einz, a WWII-era airplane hanger that was now being used as a concert venue. Not much remodeling had been done to the facility. It was cold and damp and had acoustics that were horrid for a band with boomy sound like Nirvana. Kurt hated the look of the place and cursed the fact that his career had progressed to the point where Nirvana were playing airplane hangers, though part of the reason for this was their huge fan base, which was too large and rowdy for most European operahouse venues.

At the soundcheck that afternoon, Kurt asked his tour manager for an advance on his per diem. After collecting his money, he said, “I’ll be back for the show.” Some in the crew were surprised to hear that he was leaving the facility considering that, moments earlier, he had been complaining of feeling so ill that he couldn’t stand up or play the concert. “I’m going to the train station,” he announced. Everyone in the crew and band knew that meant he was looking for Munich’s drug culture, not that he was seeking transportation.

He came back but only right before showtime. His mood had not improved but instead of tuning his instruments or preparing a set list, he began calling people. He called Courtney, and they argued. He called his lawyer, Rosemary Carroll, and in a completely uncharacteristic move, he called his 52-year-old cousin Art Cobain back in Grays Harbor, in Washington State. Art was surprised to hear from his famous cousin; they hadn’t talked in years. They made small talk, and Kurt complained about the circumstances of his life. “He was getting really fed up with his way of life,” Art later reported to People magazine. Art invited Kurt to a Cobain family reunion later that year. Kurt said he’d be glad to come.

Kurt had personally asked his childhood heroes the Melvins to open these European dates, and when their set was over, Kurt went to lead singer Buzz Osborne’s dressing room where he announced that he was ending the band, his marriage, his relationship with his managers and perhaps his whole concept of being in a band. “I should just be doing this solo,” he told Osborne. “In retrospect,” Osborne surmised, “he was talking about his entire life.”

Terminal Einz held 3,050, and the venue was filled to capacity for Nirvana’s first show in Germany in three and a half years. Few in the crowd would have noticed, but from the opening notes, Cobain looked half-dead, and his performance, which had been rote on much of the tour, was almost robotic. He began with a cover of the Cars’ “My Best Friend’s Girl,” but even this tune was redone so that it sounded slowed down and drone-like, as if Kurt had wanted to take any element of pop out of his sound. Co-guitarist Pat Smear later recalled that Kurt’s voice was indeed completely shot by Munich show. “Kurt and I were suffering from bronchitis, and his voice became noticeably more trashed with every song,” Smear told journalist Rasmus Holmen. “When we sang together, we sounded like cats fighting. His voice was sooooo gone, but instead of trying to conserve it, he seemed to delight in pushing it to the ‘I won’t be able to sing for days’ limit. After a while it was a bit much.” To Novoselic and Grohl, who had been on the road with Kurt for more years than Smear, it was obvious that if the band was going to self-destruct, it would be Kurt’s doing.

The show itself ran 23 songs, but later some remarked that it felt doomed. The power in the building went out just as Kurt began to sing the first line of “Come As You Are,” the sixth song of the set, and it was several minutes before the problem could be fixed. This kind of technical problem had happened frequently to Nirvana during their career, but never in a cold, drafty airplane hanger. Rather than wait for the crew to fix the problem, Kurt walked off to his dressing room. In some small cosmic twist, Dave Grohl’s first show with Nirvana in 1990, in a tiny Olympia club called the Northshore Surf Club, had also been plagued by power outages. That technical problem, in the nascent early days of Nirvana, had made the show more joyous, and the band played through three power outages. When the lights went out, they continued nonetheless, playing with flashlights shining on their face, as if to say that even electricity was not going to stop them.

Back in Munich, only once power was fully restored did Kurt return to the stage. Without a word or a smile, he began playing “Come As You Are” once again. The song sounded even more lifeless this time. In total, the band played 23 songs and ended with “Heart-Shaped Box,” the same song that had ended the previous eight shows. The show did not end with triumph, or any feeling of victory—it just ended.

As Kurt walked offstage he went directly to his agent Don Muller, who had flown in to make sure this show went off with problems. “That’s it. Cancel the next gig,” Kurt said without emotion as he walked to his dressing room. No explanation was given and none was needed. Kurt had been threatening to cancel the tour even before it began, and for the entire month everyone in the crew had imagined each show might be the last. Novoselic, who knew Kurt better than anyone, had sensed for months that Kurt’s interest in leading Nirvana had passed. “The band was over,” Novoselic later recalled. On March 1, 1994, the only thing that officially ended was this single leg of the In Utero European tour, but everyone knew that a larger story was coming to a close. Finally, in a drafty abandoned airplane hanger in Munich, in circumstances almost as dreary as their genesis, Nirvana ended.

Just a few days later in Rome, Kurt tried to kill himself by taking three-dozen Rohypnol, a powerful tranquilizer that is commonly known as the “date rape” drug. He’d left a note that referenced Shakespeare: “Like Hamlet, I have to choose between life and death. I’m choosing death.” He was rushed to a hospital and did not die, though several news reports announced that he had. Novoselic was back in Seattle and got a phone call from management saying Kurt was dead. CNN ran a news flash on Cobain’s death, as did a wire service news bulletin.

Kurt came out of a coma that afternoon and was back in Seattle two days later. He spent much of the next month on a heroin binge. His usage was so reckless that even his drug buddies began to shun him, worried that he might die in their presence. When one warned Kurt that he was using enough dope to kill himself accidentally, Kurt replied that he intended to shoot himself.

Several interventions were attempted, and finally on March 30, Kurt agreed to give rehab another chance—he had tried four times before. He checked into the Exodus Recovery Center in Marina Del Rey, California, but left after less than 48 hours. On the flight back to Seattle, he sat next to Duff McKagan of Guns N’ Roses. “I could tell he was bumming,” McKagan recalled. Duff offered Kurt a ride home, but Kurt split before they connected.

Over the next week Kurt went missing, and eventually a police report was filed and a private investigator was hired to locate him. He spent much of the time in seedy motels using drugs. Sometime during the first week of April, most likely on April 5, he snuck back into his mansion, which was now empty of family.

On April 8, 1994, an electrician servicing the house discovered a body in the greenhouse. It was Kurt. He had killed himself with a shotgun, leaving a long suicide note next to him. He ended the note by quoting Neil Young: “I don’t have the passion anymore and so remember, it’s better to burn out than to fade away. Peace, love, empathy. Kurt Cobain.”

“I knew the spirit of the Alice Cooper group was back – what we were making was very much an album that could’ve been in the '70s”: Original Alice Cooper lineup reunites after more than 50 years – and announces brand-new album

“The rest of the world didn't know that the world's greatest guitarist was playing a weekend gig at this place in Chelmsford”: The Aristocrats' Bryan Beller recalls the moment he met Guthrie Govan and formed a new kind of supergroup