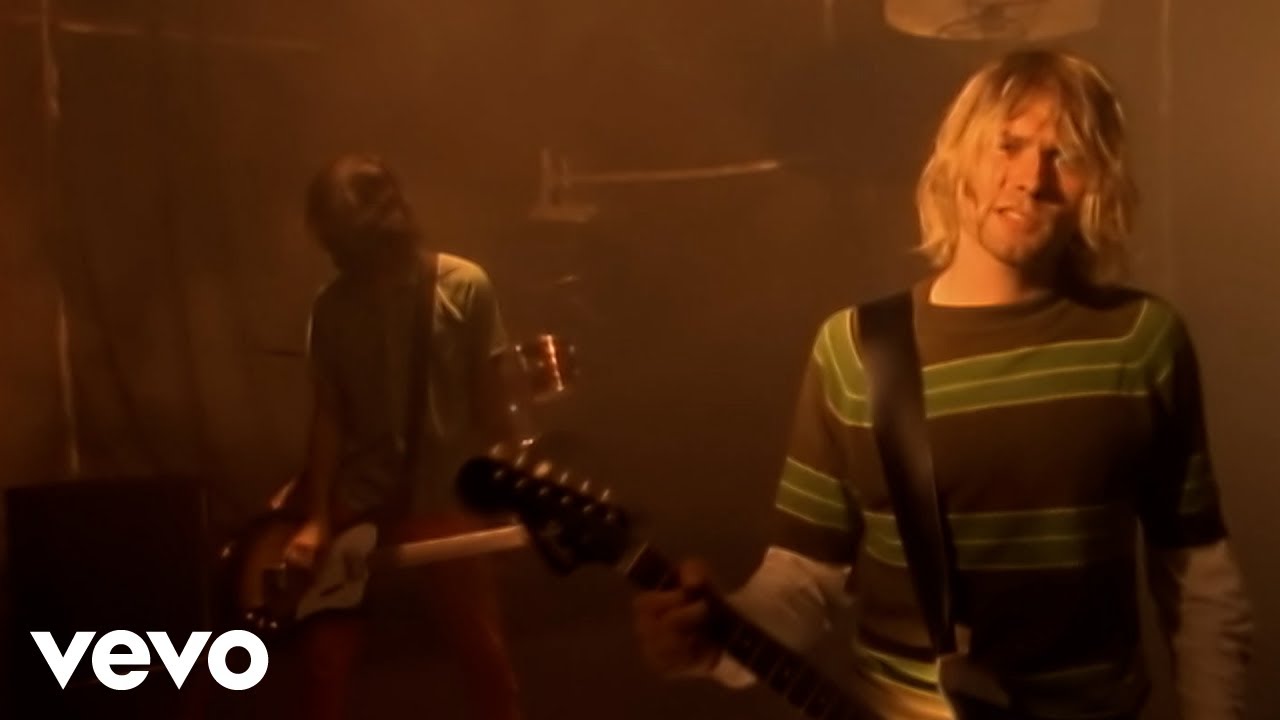

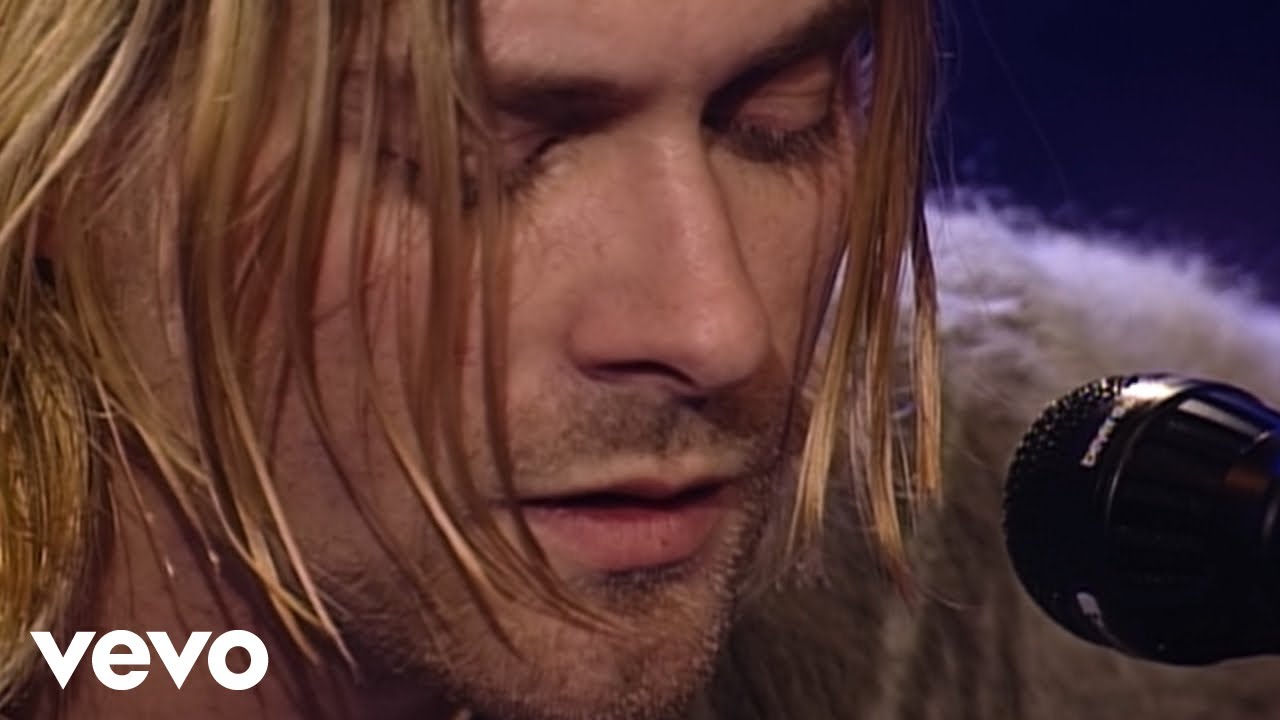

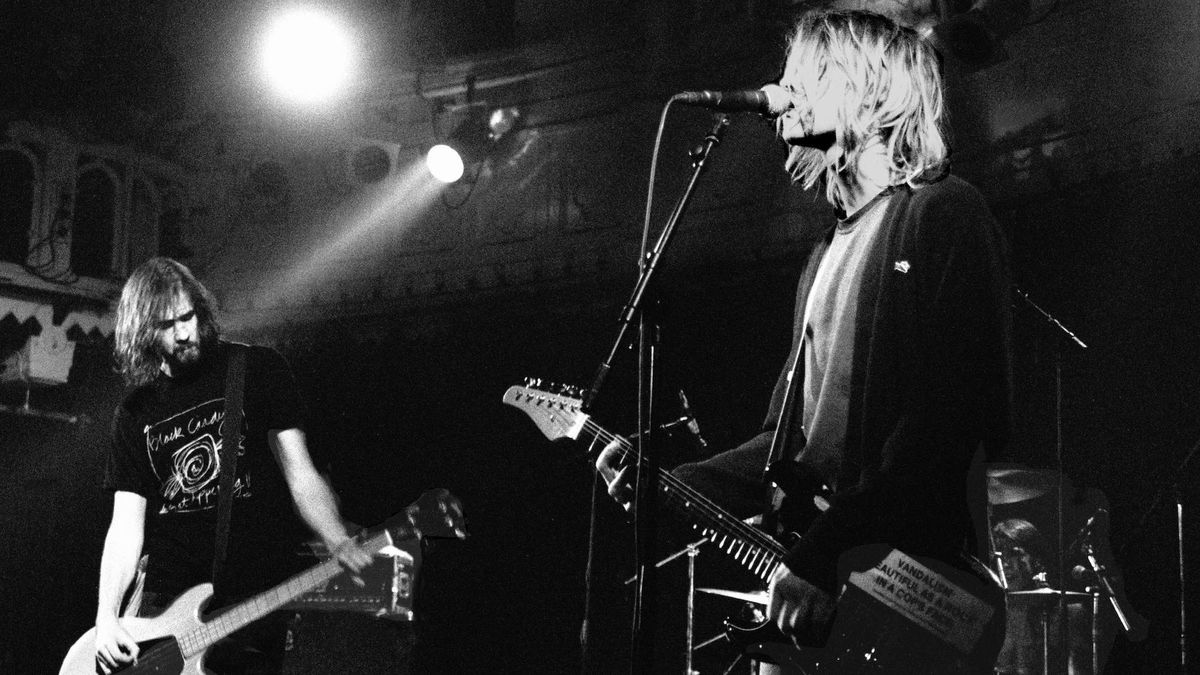

“Kurt launched into that track and totally went off. In the middle of the song, he smashed his guitar to bits”: The making of the album that virtually invented a new genre, sold 30 million copies, and changed rock forever

One of the best-selling albums of all time, Nirvana's Nevermind re-shaped popular culture and guitar-based music almost overnight. This is how it was made

Nearly 15 years have passed since the release of Nirvana’s Nevermind on September 24, 1991. As of this writing, the record has sold tens of millions of copies, and continues to sell some 2,500 copies per week – proof that Kurt Cobain’s music and his world-weary lyrics still resonate deeply.

But consider this: those teens whose lives were changed by Nevermind are now parents themselves. 10-year-olds who bought the album when it first came out are now deep in the throes of adulthood. And twenty-somethings who picked up on Nevermind have either just passed the Big Four-O or are rapidly approaching it.

Which is to say, Nevermind has attained classic status. It is one of those rare albums that will accompany its original fans on their journey through life, while continuing to attract new generations of listeners.

If Nevermind doesn’t seem like an old record, it’s partly because over the past 15 years, the rock scene has been entirely remade in its image. But the world into which Nevermind was born is one that a present-day rock teen would hardly recognize. Alternative rock and heavy metal were still very distinct, mutually hostile genres. Nirvana invaded both camps, converting troops from both sides to the army of flannel-shirt-wearing grunge rockers.

The trio from the rugged Northwest altered the world of mainstream pop as well, knocking Michael Jackson from his perch atop the charts. In doing so, they paved the way for “alternative mainstream” success stories like Pearl Jam, Alanis Morissette, Bush, Stone Temple Pilots, and Rage Against the Machine.

Like Frampton Comes Alive or Meet the Beatles, Nevermind is one of those records that gets incredibly successful in a way no one could have predicted or can ever quite explain. Its explosion into the mass culture firmament surprised Kurt Cobain, Krist Novoselic, and Dave Grohl just as much as it did anyone else.

“You want to know why we’ve taken off?” Grohl told Circus magazine in 1991. “We have no idea. We had no idea it would ever get this insane.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I’m constantly feeling guilty in ways,” Cobain told journalist Michael Deeds shortly after Nevermind’s release. “Our music, especially on this album, is so slick-sounding. A few years ago, I would have hated our band, to tell you the truth.”

Nevermind represented a quantum leap for Nirvana, both musically and career-wise. Their previous album, Bleach, was recorded in three days and cost $606.17 to make. Their initial budget for Nevermind was $65,000 – 100 times larger than the budget for Bleach. They ended up spending twice that amount. And while Bleach, which was Nirvana’s debut album, came out on the then-little-known indie label Sub Pop, Nevermind had the major-label clout of Geffen Records behind it.

The two-year period that separates Bleach from Nevermind was a time of tremendous growth and upheaval for the band. They went on their first national and international tours. Cobain started up and broke off a relationship with Tobi Vail of the band Bikini Kill. What’s more, Nirvana went through several personnel shifts.

Guitarist Jason Everman, who joined shortly after Bleach, exited the band nearly as quickly as he’d come aboard, once it became clear that his tastes were more hard rock/metal than his bandmates’. He later joined Soundgarden.

Chad Channing, who played drums on Bleach, left the band. Nirvana’s original drummer, Dale Crover, filled in for a seven-date West Coast tour. Dan Peters of Mudhoney played drums on a Nirvana single called Sliver and did one gig with them before Dave Grohl finally settled into place as the group’s permanent drummer.

The frequent personnel shifts and extensive touring seemed to have honed the band’s songwriting, as such experiences often do.

The process also seems to have sharpened the band’s pop sensibilities, which are in far greater evidence on Nevermind than on the sludge-guitar heavy Bleach. But Nirvana biographer Michael Azerrad suggests that those same pop sensibilities existed all along, and that Cobain deliberately suppressed them on Bleach in an effort to conform with Sub Pop’s retro Seventies metal agenda of that time.

“Half of the songs on Nevermind were written at the time of Bleach, but didn’t make it onto the album,” Cobain told journalist Roy Trakin. “So there really isn’t an obvious change. We’ve always been fans of pop music.”

A major milestone along the road to Nevermind came in April of 1990, when Nirvana began recording with producer Butch Vig at Smart Studios, his recording facility in Madison, Wisconsin.

Now perhaps best known as the leader of the band Garbage, Vig was then an up-and-coming indie producer whose credits included well-regarded records by the Laughing Hyenas, Smashing Pumpkins, Firetown, Tad, and Killdozer, among others.

In the week Nirvana spent at Smart, they recorded six songs that would later turn up on Nevermind: In Bloom, Dive, Lithium, Breed (originally titled Imodium), Stay Away (originally titled Pay to Play), and Polly. They also made an unsuccessful stab at another tune, Sappy, which they’d attempted to record at an earlier date, also with unsatisfactory results.

The Smart sessions were originally intended for release as Nirvana’s second album on Sub Pop. But a series of events led the band to change their plans. First, Chad Channing left Nirvana in May 1990. And then the prospect of major-label interest started to become more than an idle rumor.

“We lost Chad and there was uncertainty with that,” Novoselic told a radio interviewer in Australia.

“We didn’t want to release [the Smart sessions]. If we did anything, we wanted it to be with a new drummer. [Also] Sub Pop was doing some wheeling and dealing. They were going to sign a licensing deal with a big label, and that kinda scared us. There were so many variables to consider; it wasn’t wise to put out a record at all.”

We came up with so much stuff where we’d go, ‘God, this is the best thing we’ve ever done!’ Then we’d forget how to play it

Dave Grohl

Polly is the only song on Nevermind that was recorded at Smart; all the other tracks were re-recorded (although the final versions are said to be very similar to those laid down at Smart).

As for Polly, the band and producer realized there was something special in Cobain’s solo acoustic performance of this disquieting rape scenario, which was based on an actual newspaper account he’d read. The dramatic twist was that the very anti-violence, pro-woman Cobain sang the song from the attacker’s point of view.

“Just because I say ‘I’ in a song doesn’t necessarily mean it’s me,” Cobain later commented. “A lot of people have a problem with that. It’s just the way I write, usually – taking on someone else’s personality or character. I’d rather just use someone else’s example, because, I dunno, my life is kinda boring. So I take stories from television, and things I’ve read and heard.”

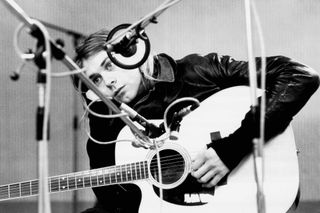

“Polly was done with a really cheap acoustic five-string guitar that Kurt had,” recalls Vig. “It had this plunky sound. The original strings were still on it. He never changed them, and he never tuned the guitar either. It was down about a step and a half from E.”

Earlier on, Nirvana had attempted to record a full-band electric version of Polly for their Blew EP. The acoustic performance on Nevermind is no doubt closer in spirit to the song as it sounded when Cobain first wrote it. It also sheds light on the dynamic between Cobain as a songwriter and the rest of the group as interpreters of his material.

“It [songwriting] is usually done on an acoustic guitar, sitting around in my underwear, just picking out riffs, pieces of songs,” Cobain said on Australian radio.

“Krist and Dave have a big part in deciding on how long a song should be and how many parts it should have. So I don’t like to be considered as the whole songwriter. But I do come up with the basics of it. I come up with the singing style and I write the lyrics, usually minutes before we record.”

Grohl became a member of Nirvana in September of 1990, joining them from the Washington D.C. hardcore band Scream. His muscular yet agile drumming took Nirvana’s power trio sound to a new plateau.

Grohl’s arrival also sparked a fresh burst of group songwriting. In a Tacoma, Washington rehearsal space that they shared with a local bar band, Nirvana embarked on a regimen of daily, 15-hour band practices for a period of four or five months.

“We came up with so much stuff where we’d go, ‘God, this is the best thing we’ve ever done!’ Then we’d forget how to play it,” Grohl told Circus magazine. “So many songs got thrown away, until we finally said, ‘Maybe we should start recording them on a cassette.’ So we’d record them, then lose the cassette.”

Two songs that didn’t get away were Smells Like Teen Spirit and Come As You Are, tunes that would prove to be cornerstone tracks of Nevermind. The attention-grabbing title of Teen Spirit was born on a typically relaxed evening at the Cobain residence, as Kurt explained to Australian radio listeners.

“A friend of mine and I were goofing around my house one night. We were kinda drunk, and we were writing graffiti all over the walls of my house. And she wrote, ‘Kurt smells like Teen Spirit.’

I felt more pressure making that record than they did, because it was really the first major-label record I had made

Butch Vig

“Earlier on, we’d been having this discussion about teen revolution and stuff like that. And I took [what she wrote] as a compliment. I thought she was saying that I was a person who could inspire. I just thought it was a nice little title. And it turns out she just meant that I smelled like that deodorant [called Teen Spirit]. I didn’t even know that deodorant existed until after the song was written.”

Geffen Records had been taking an active interest in Nirvana since April 1990, when Gary Gersh – then an A&R man for Geffen and currently head of Capitol Records – saw the band play at the Pyramid club in New York.

Gersh had been brought to the show by Kim Gordon and Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth. This set in motion a chain of events that would lead to Nirvana’s signing with Geffen. The deal was formally consummated on April 30, 1991. In May, the band arrived in Los Angeles to begin recording what would become Nevermind.

According to Come As You Are, Michael Azerrad’s 1994 Nirvana bio, it was at the suggestion of Gary Gersh’s that the band re-recorded their six Smart session tracks for Nevermind. But it was Nirvana’s own call to use Vig as a producer. They chose him over several bigger name producers, including Scott Litt, Don Dixon, and David Briggs. Apparently, Vig’s work on the Smart sessions had impressed the band.

“Butch was just easy to work with,” Novoselic told Australian radio. “Laid back and really attentive to what’s going on. He works hard but he doesn’t work the band hard.”

Butch Vig says that the band, glad to be in sunny Los Angeles, were generally in good spirits for the Nevermind sessions.

“Kurt was enjoying himself when we made that record. That was before they got really big, and they had kind of a casual attitude toward making the record. There wasn’t a lot of pressure – I felt more pressure making that record than they did, because it was really the first major-label record I had made.”

With an initial budget of $65,000, the band could certainly take a more leisurely approach than they’d taken with Bleach. They began with three days of preproduction, running down the tunes with Vig in a North Hollywood rehearsal hall. One of the first things Vig noticed was the huge impact Grohl’s arrival had made on the band’s sound.

“Kurt had called me up and said, ‘I’ve got the best drummer in the world!’ I thought, ‘Yeah, right. I’ve heard that one before.’ But the first time we went in that rehearsal space and started running through the songs, it was just amazing. Dave was incredibly powerful and dead on the groove. I could tell from the way Kurt and Krist were playing with him that they had definitely kicked their music up another notch, in terms of intensity.”

The preproduction chores were fairly light work: Nirvana had already recorded half the material with Vig once before, and they were well rehearsed on most of the newer tunes.

“Frankly, I didn’t want to beat the songs into the ground,” says Vig. “I just wanted to hear the arrangements and maybe tighten things up a little bit.”

Vig had already heard a rough rehearsal cassette of Teen Spirit but he was knocked out the first time he heard Nirvana play it live in the rehearsal room. “I kept having them play it over and over again, because it was so fucking good! I was literally pacing around the room, saying to myself, ‘This is amazing!’

He launched into that bonus track on the CD and just totally went off. In the middle of the song, he smashed his guitar to bits

Butch Vig

“There wasn’t much that needed to be done with the song. I think we did a little arranging. At the end of each chorus, there’s a little ad lib thing Kurt did with the guitar. Originally that only happened at the end of the song; he did it a whole bunch of times. I suggested moving that up in to each chorus and cutting the choruses down a little bit. Just some minor tweaking of the arrangements.”

From there, the band moved over to Sound City Studios in nearby Van Nuys. A funky old place in a poor, largely Hispanic part of the San Fernando Valley, Sound City has a good classic rock and metal track record (Fleetwood Mac, Foreigner, Petty, Dio, Crazy Horse, Ratt). Most importantly, the studio has what Vig and the band felt they needed in order to get the primal rock sound they were after: a large recording room and a vintage Neve console.

“At that point, I’d never done any work in Los Angeles,” says Vig. “But I knew that was where the band wanted to work, and I knew of Sound City’s reputation. I worked out a deal so it was cost-effective for us to go there. It was sight unseen. We just booked it and went in.”

On a typical day, says Vig, “we’d be in the studio by around noon or one and we’d leave around midnight or one in the morning.” The band set up in Sound City’s large room, Studio A, to record basic tracks.

“When we cut basics, it went pretty fast,” Vig recalls. “I think it took five or six days in all. Dave was set up in the middle of the room. We built a big drum tunnel on the front of his bass drum, so we could mike it from a distance and still isolate it from all the bleed in the rest of the room. Chris had his SVT bass rig off to the side, but he could play in the room. His headphones were set up next to the drums.

“Kurt’s amps were in a little isolation area, but he was also in the room and he could sing into a mic. We’d start running a song down and they’d usually get the basic track in two or three takes. If there was a missed chord or a bad bass note, we’d go back and punch in [the correct notes] right away.

“Territorial Pissings was basically a first take. Lithium was a little harder. That was the only track we used a click track on at the start of the song, because, for whatever reason, the band kept speeding up really fast. We decided that we wanted to keep it at a real even tempo. Dave had never played with a click track before, but it was not a problem for him at all. After three or four takes with the click, we nailed it.

“After the first couple of takes of Territorial Pissings, that’s when they did that song, Endless Nameless [the surprise noise track that kicks in 13 minutes and 51 seconds after the end of the album’s ostensible final song, Something in the Way].

“Kurt got really frustrated because the song kept speeding up and they were just not playing particularly tight. And he launched into that bonus track on the CD and just totally went off. In the middle of the song, he smashed his guitar to bits. So we spent the better part of the rest of that day driving around Los Angeles trying to find a left-handed replacement guitar.”

Another problematic track was Something in the Way.

“They originally wanted to cut it as a full-on band,” Vig explains. “But that proved difficult to record. It just was not happening. Kurt was not very happy. Finally he came over to me and said, ‘It needs to sound like this…’ And he picked up his old five-string acoustic guitar [the same one used on Polly]. He sat on the couch in the control room and started to sing and play.”

Realizing he was on to what could be a master take, Vig quickly set up some microphones.

“I turned off the air conditioner and everything else and had the phones shut off. He was playing and singing so quietly. But we got it down on tape. Later on, we overdubbed drums and Kurt added some harmonies. But it was all built around the acoustic track.”

Vig remembers Cobain as someone who was generally willing to let others share in his creative processes.

“He was pretty open to all sorts of ideas. He had different lyrics he would bring in and show me. And he’d say, ‘I got a couple of melodies here. Which one do you like better?’ And he’d sing the song in a couple of different versions and I’d give him some feedback on it.”

After basic tracks were completed, Nirvana moved over to Sound City’s other, smaller room, Studio B, for overdubs.

“We started adding the second rhythm guitar to songs,” says Vig, “and Kurt started working some more on his vocals. Dave did some harmonies.”

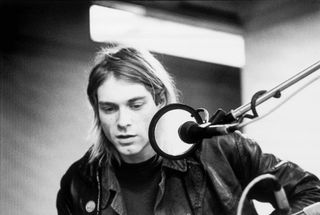

Lead vocal sessions were generally done in a one-on-one setting, with just Cobain and the producer present. The vocal mic was set up in the main studio area, “but it was basically like a lounge area,” says Vig.

“There were candles in there, and a big rug on the floor. A pretty cool vibe. Dave and Krist were around, but they’d be off playing pool or watching TV. They’d pop in to the control room and listen every now and then, but Kurt kind of wanted to be left alone when he was doing his vocals. He also didn’t really like to use headphones when he sang, so we set up a fairly elaborate system where he could use speakers.”

Cobain’s legendary impatience with multiple takes came to the fore at this time.

“He really wanted to do everything on the first or second take,” says Vig. “He’d do a couple of takes and say, ‘That’s it. I’m not gonna do it anymore.’ The tricky part was trying to figure out how to motivate him to give really good performances. Sometimes his first or second takes were brilliant, but sometimes they needed work. They needed to be more focused.

“What I ended up doing was recording everything he sang, even the warm-ups. A lot of times, I’d actually be going for a first take, but he would think it was just a warm-up. Then I’d have the engineer flip to a new track and I’d tell Kurt, ‘Okay, you’re ready for your first take.’ If I was lucky, I could get as many as four takes out of him. Then I’d take the best pieces of each one and make a master out of it.”

Cobain’s painful, undiagnosable stomach condition would sometimes bring sessions to a halt, Vig remembers.

“He was very sensitive to certain foods. Sometimes we’d eat dinner and he’d get sick half an hour later and end up spending 45 minutes in the bathroom. He was constantly taking Pepto Bismol and things to relieve some of his pain.”

But for all that, the mood in the studio was generally upbeat.

Andy Wallace was on the list of mixers. It said ‘Slayer’ next to his name. And Kurt said, ‘Get this guy’

Butch Vig

“Kurt and Krist were really happy that Dave had joined the band,” says Vig. “They were in L.A., they’d just signed a record deal with Geffen, they had a bit of cash, so they’d go out and do a little partying. I know they used to go down to Venice and stay up all night.

“After we’d finish working in the studio at midnight or one, they’d go and stay out 'till the sun came up. So sometimes I’d get to the studio at one and they wouldn’t show up till three because they’d slept in. But basically, they showed up when they needed to show up. There wasn’t any real serious partying going on in the studio. They were there to work.”

While in L.A., the band stayed at the Oakwood Apartments in nearby Universal City.

“A couple of times I went to pick them up there and they had definitely turned their place into a bachelor pad. There were cans of food lying open everywhere and clothes thrown all over the place and acoustic guitars lying around the room.

“I know they were getting a big kick out of staying there because the band Europe was staying next to them. That was the band that had a big hit in the Eighties with The Final Countdown. The guys in Europe would all go sit out with their girlfriends by the pool everyday. And I remember Krist and Dave and Kurt making fun of them. They were not big Europe fans.”

Working at Sound City at the same time as Nirvana were the Sidewinders, an Arizona band Vig had recorded that was now working with David Briggs (whom, embarrassingly enough, Nirvana had rejected as a producer for Nevermind).

Vig recalls that the guys in the Sidewinders “kept coming by and asking, ‘Wow, can you play us some stuff that Nirvana’s doing?’ That was the first sense I got that there were people out there who were really totally obsessed with Nirvana.”

The band reached the end of the 16 days booked at Sound City before they had finished overdubbing. Vig booked an additional four or five days at Devonshire Studios in nearby Burbank, where Nirvana completed their overdubs and did some preliminary mixing.

One of the very last overdubs to be completed was the cello part on Something in the Way, the track that had given them difficulties all along. The cello part was played by Kirk Panning.

“That song really wasn’t even written until a week before we went into the studio,” Cobain told Australian radio. “I knew I wanted cello on it, but after all the music was recorded for it, we’d kinda forgotten about putting a cello on. We had one more day in the studio and we decided, ‘Oh geez, we should hire a cellist, you know, and put something in.’

“We were at a party and were asking some of our friends if they knew anyone who could play cello, and it just happened that one of our best friends in L.A. is a cellist. So we took him into the studio on the last day and said, ‘Here, play something.’ And he came up with a part right away. It just fell in like dominos.”

From a technical standpoint, however, it wasn’t all that easy.

“Kirk is a good cello player,” says Vig, “but we had a hard time getting his instrument in tune with Kurt’s guitar. That old five-string acoustic of Kurt’s was tuned down a few steps and wasn’t really tuned to any standard pitch. I remember I fretted over the whole track. It was tricky getting Krist's bass in tune with the guitar, too. You couldn’t use any kind of a standard tuner.”

While at Devonshire, Vig and the band also took a first stab at mixing the record.

“I mixed three or four tracks with the band,” says the producer, “but none of us were very happy with how they came out. To me, they sounded too rough. Kurt would say, ‘Take all the high end off the guitars.’ And I would say, ‘I don’t want them to sound muddy.’ There was also a tendency to bury the vocals more. The mixes sounded more punk rock that way, but the songs didn’t sound as focused to me.”

Ultimately, they decided to call in someone else to mix the album. Geffen’s Gary Gersh sent over a list of possible names.

“Scott Litt was on top of the list,” Vig recalls, “but Kurt said, ‘No, I don’t want to sound like R.E.M.’ Ed Stasium was also on the list. To which Kurt said, ‘No, I don’t want to sound like the Smithereens.’ He went all the way to the bottom of the list and Andy Wallace was there. It said ‘Slayer’ next to his name. And Kurt said, ‘Get this guy.’”

The mixes were done at Scream, another San Fernando Valley studio.

“Basically, I’d let Andy go over the tracks by himself for a few hours,” Vig recalls. “When he got everything up, he’d call me in, and I’d bring in the band and we would nit-pick stuff. Basically, we mixed a song or two a day. The whole record took nine or 10 days to mix.”

Despite the fact that Wallace was Cobain’s own choice and that the band participated in the mixing process, Cobain would later complain to the press that Wallace’s mixes made Nevermind sound too slick, and that it was “closer to Mötley Crüe than a punk rock record.”

“But I think part of that was just Kurt’s reaction to having Nevermind be so successful,” Vig speculates. “If it had only sold 50,000 copies, he probably wouldn’t have had any comments on whether it was too slick or not slick enough.”

By the time the finished masters were handed to the label, the band had spent $130,000, which, despite being twice their initial budget, is still a relatively small amount for a multi-Platinum album. With the music out of the way, attention turned to the cover art.

“One day Dave and I were sitting around watching a documentary on babies being born under water,” said Cobain in his Australian radio interview. “I thought that was a really neat image, so we decided, ‘Let’s put that on the album cover.’ Then when we got back a picture of a baby underwater, I thought it would look nice [to add] a fish hook with a dollar bill on it. And so an image was born.”

The back cover of Nevermind features a photograph by Cobain taken some years earlier, with a background comprised of a collage he made from photos of raw meat, vaginas (according to some accounts), and figures from a painting of Dante’s Inferno. In the foreground is Chim Chim, his toy monkey who’d appeared in earlier Nirvana artwork.

“I was in a bohemian photography stage, you know?,” Cobain later said. “If you look real close, there’s also a picture of Kiss, in the back, standing on a slab of beef.”

Nevermind was released on September 24, 1991. Like all rock albums, it documents the artists’ world at the time the record was made. This momentous recording happened to catch Nirvana at a high point: in the midst of a creative groundswell, somewhere between obscurity and superstardom.

“We’re experiencing the typical independent-band-going-onto-a- major-label punk rock crisis,” Cobain said in 1991, shortly after Nevermind was released. But he also acknowledged the existence of something more important than passing musical fashions and fickle perceptions of “credibility” and “authenticity.” On a level beyond all that, he appeared to realize that the songs on Nevermind could stand the test of time.

“People have opened up to an appreciation of hard rock in punk, and it’s great that they’ve fused together,” Cobain told Monday Morning Replay in December 1991. “Now it’s time to appreciate the pop side. Attitude is one thing. But a good song is the most important thing. It’s the only way to really touch someone.”

This feature was originally published in Guitar World in 2005.

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

“We’re deeply proud of and beyond grateful for the music and history we’ve shared, and we wish him nothing but success and happiness in his future endeavors”: Mastodon part ways with Brent Hinds

“The musicologist looked me square in the eye and said it couldn’t be done”: Meet Lowen, the heavy trailblazers defying metal rules by playing prog-doom in Middle Eastern and North African styles – scoring them a support tour with Zakk Wylde