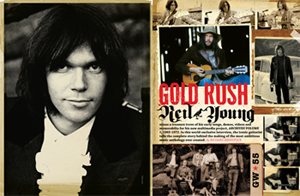

Neil Young: Gold Rush

Originally published in Guitar World, October 2009

Neil Young mines a treasure trove of his early songs, demos, videos and memorabilia for his new multimedia project, Archives Volume 1, 1963-1972. In this world-exclusive interview, the iconic guitarist tells the complete story behind the making of the most ambitious music anthology

ever created.

"How're you all doing?”

It’s June 2009, and Neil Young is standing center stage at the O2 in Dublin, an ultra-modern, orb-like arena that seems as much a food court and concession stand as it does a music venue. He’s wearing baggy blue jeans, sneakers and a corduroy button-down over a faded black T-shirt. His hair is grey, and wild as ever, with bushy mutton-chop sideburns framing either side of his face. Young is nearing the end of a European tour in support of Fork in the Road, which is, roughly speaking, the 34th or so album of his solo career. Taking into account live discs, soundtracks, projects with other bands, and the nebulous nature of what exactly constitutes an “official” album in Young’s catalog, it’s probably closer to being his 50th. Last year Young turned 63, but tonight he’s been stomping the stage and flailing his body with abandon, all the while coaxing some incredibly gnarly, earsplitting tones—even for him—from “Old Black,” the heavily modified 1953 Les Paul goldtop that in its own way looms as large in music history as Young does.

“We got one for you,” he continues from the stage. “May not be the one you wanted.” Young moves away from the microphone to cue the next song. Then he changes his mind and steps back up. “Or,” he adds, “it might be.”

With that, Young and his band launch into the jangly, upbeat “Burned,” a not-quite-unfamiliar, but certainly not well-known, tune he first cut with Buffalo Springfield back in 1966, and which he once identified as his “first vocal ever done in a studio.” Since that day more than 40 years ago, the song has rarely, if ever, been played live. But Young’s been in a different kind of mood lately.

Last year, for instance, Young took to performing “The Sultan,” a twangy, Hank Marvin–inspired instrumental that he recorded in 1963 while a teenager in Canada, with his first real band, the Squires. The reference was probably lost on all but the most devoted fans in attendance, and Young added an extra layer of absurdity to his performance by having a man dressed as a sultan bang on a gong to introduce the song.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Discussing this episode today, Young finds it all rather amusing. “We had one lying around backstage,” he says, referring to either a sultan’s outfit, or perhaps an actual sultan. “So we wanted to get him out there.”

But beyond an easy laugh, there’s another reason Young has been unearthing songs like “The Sultan” and “Burned” on recent tours. He’s been knee-deep in a journey through his past, and now, with the release of the long-delayed, nearly 20-years-in-the-making Neil Young Archives Volume 1, 1963-1972, so are his fans.

The first of what Young envisions will ultimately be four or five installments (each spanning roughly a 10-year period of his career), Archives Volume 1 is, to put it lightly, massive. Issued in three formats—as a 10-disc Blu-ray or DVD collection, each with a 236-page book, and as an eight-CD set—the retrospective boasts more than 120 songs from Young’s first decade as a musician, beginning with the Squires and continuing through Buffalo Springfield, his early solo work, Crazy Horse, and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. The tracks are grouped by era: for example, the Buffalo Springfield period resides on a disc titled Early Years(1966-1968), while the Harvest record is chronicled on North Country (1971-1972). The Archives set features many of Young’s biggest and most enduring songs, from acoustic standards like “Sugar Mountain,” “Tell Me Why” and “Heart of Gold,” to Buffalo Springfield and CSNY classics like “Mr. Soul,” “Ohio” and “Helpless,” to Crazy Horse barnburners like “Cinnamon Girl,” “Down By the River” and “When You Dance, I Can Really Love.”

Practically half of these performances are unreleased recordings, live cuts, outtakes and alternate mixes. In addition, the Blu-ray and DVD sets house an excess of visual ephemera, including concert performances, TV appearances, photos, letters, newspaper articles, original manuscripts, audio and video interview clips, and the full version of Journey Through the Past, Young’s 1972 feature film directorial debut. These materials are organized around two primary tools: a virtual filing cabinet in which each song and its relevant audio and visual documents are gathered in their own individual folder, and an interactive timeline that runs through all the discs and places Young’s music within the appropriate personal and historical context.

To call Archives merely a “box set” would be to miss the point entirely; it is, in essence, the most panoramic, comprehensive-to-the-point-of-obsessive audio-visual product ever issued by a recording artist.

“What we’ve done is something that’s never been done before,” Young says matter-of-factly, sipping a Guinness in the lobby of the Four Seasons hotel in Dublin on the afternoon prior to the O2 show. “ ‘Necessity is the mother of invention,’ I guess is the phrase. And that’s where this came from. I needed this.”

The invention that Young refers to is Blu-ray, his preferred platform for viewing and listening to Archives. In edition to offering superior sound—state-of-the-art 24-bit/192kHz ultra-high resolution, compared with DVD’s 24-bit/96kHz and CD’s 16-bit/44kHz standards—the format allows two additional features unavailable on any other platform. Unlike DVD, Blu-ray lets users listen to music and scroll through documents simultaneously. This means that while playing the audio track to Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young’s “Ohio,” the listener can also peruse, among other things, recording information about the track, photos of the band onstage at the Fillmore East in New York, Young’s original handwritten manuscript of the lyrics, Time and Life magazine covers about the Kent State University shootings that inspired the subject matter, and a copy of the 45 single and sleeve. There is also audio of Young discussing the song in a radio interview, and video of CSNY performing it at a show in Boston, with the audience singing along to every word.

The other technological development at the center of Archives is BD-Live, which enables Blu-ray users to download free updates in the form of additional songs, videos and other documents, as Young makes them available. Once downloaded, these materials appear in their appropriate chronological spots on the interactive timeline.

As Young explains, BD-Live makes it possible for Archives to be an evolving, evergrowing project. “It takes a certain kind of organization to come up with that stuff,” he says. “These aren’t things that somebody kept; these are things that everybody kept. And we had to find each person. We had a scanning network out there. And the reason it’s so detailed is because we took a lot of time. A long time. So new pieces of material are always being uncovered. And because of BDLive we’ll be able to continue getting it out there forever. It’s never finished.”

That said, Young has already moved on to the second installment of Archives, which will take him into the early Eighties. He expects it to be assembled in less time than Volume 1. “It’d be hard to not be quicker.” He laughs. “That one was, like, 20 years. I think we’ll see Volume 2 in about two or three years, tops.”

Young recently sat down with Guitar World for his first, and only, comprehensive interview about Archives Volume 1. In the following wide-ranging discussion, he expounds on the classic songs and great musicians heard on the collection. He also delves into the guitars, amps and recording techniques that went into creating the timeless music, and speaks candidly about songwriting and his own instrumental abilities.

Most of all, Young was eager to talk about the Archives project itself and in particular how, in his view, the benefits of the technology offered by the Blu-ray format will reverberate far beyond his own music.

“People don’t understand the value of sound anymore,” Young says. “But somebody’s going to have to have the nerve to rescue an art form. My responsibility here is to show that music can be supplied at a higher quality, and with deeper content. I’m making it available.”

He continues. “Where I came from, music was God. So I must be a dinosaur, you know? Like my day is over. But the fact is, my day is still ahead of me.”

GUITAR WORLD You’ve been talking about the Archives project for close to two decades, and countless release dates have come and gone. Now that it’s finally here, one of the things I find amazing is that as far back as the early Nineties you were adamant that certain technologies—such as the ability to scan documents onscreen while simultaneously listening to the music—needed to be in place in order to deliver the project as you saw fit. You knew what you wanted, but you needed to wait for the technology to catch up.

NEIL YOUNG I knew that it had to be this way, and I believed it was gonna happen. I just thought it would happen sooner. I actually thought DVD would do it. But DVD didn’t cut it. So Blu-ray came along just in time. It was only about two years ago that we really saw what we could do with this format. And then it was only more recently that we discovered the BD-Live feature and the possibilities there. That was something that we uncovered while putting together the timeline that binds all the discs together. And new discoveries keep popping up. It’ll continue to grow as the Blu-ray standard grows.

The thing with Archives is that you’re not just getting a music Blu-ray; you’re getting something that no movie Blu-ray has ever done, that no educational Blu-ray has ever done. On a broader scale, we’re trying to create a new flow of information. In my case, the music is the glue that holds it all together. But it could be anything—it could be art, it could be film, it could be history. As far as I’m concerned Archives is a great opportunity to build this platform, and we’ve pushed the walls of the technology already. And the developers love that. We’re helping.

GW So how many Archives sets are we looking at?

YOUNG Maybe four, maybe five. It depends on how much cutting and paring down we do, and how much we get into using BD-Live, which is really a great thing. It’s tremendous. It’s remarkable because we really only saw that aspect of it for the first time six or seven months ago. And even then it was cobbled together and the software was buggy. The developers didn’t show me too much, because they were still working on the technology. I’d say, “Is it working yet?” And the developers would say, “No.” So all right, I don’t have to look at it. And then finally it got to a point where they said, “We think it’s working pretty good, you oughta check it out.” And even then we were just looking at the technology: How does it work? Can you listen to music while you’re scrolling around? What types of updates can we do with BDLive? How are the updates going to sit on the timeline?

One thing that we figured out is that we’re going to be able to do progressive download updates. So for instance, around 1970 I played a show at the Cellar Door club in Washington, D.C. That show was taped, but we don’t have enough great takes to release it as its own disc. Instead, I’ll probably make the songs available as downloadable updates to Archives. We’ll drop them onto the timeline, one at a time. So one day you may receive an update that will allow you to download the first song from that show, and then maybe a week later, you’ll get an update with the second song. And then the third song will come the next week. Before you know it, you have 40 minutes of music in high-def sound that you didn’t have to pay for, and that no one’s ever heard before.

GW On a more personal level, why did you feel the need to gather your work in this manner?

YOUNG Well, my music and the way it’s presented here are really inseparable. I have this thing that I’m doing—I’m telling a story. It’s something that I’ve wanted to do for a long time, and in doing it I’ve become part of the creation of a technology platform that is so much more far-reaching than what I originally envisioned. And I’m fascinated by that. My music has become a way to demonstrate a navigation system through time. And really, my life, my own content, is almost secondary at this point. I look at Archives and I go, “Well, there’s a hell of a lot about me in there.” If you’re interested in that, then great. If you’re not interested in me, then just listen. Because what you’ll hear is better than any record you’ve ever had. And there’s an era coming up in which this level of sound quality, and this level of interaction, is going to be the standard. Much like the CD was the standard for the previous era.

GW Assembling Archives afforded you the opportunity to view the contents of your musical life fairly comprehensively. Was there any overall pattern of behavior that revealed itself to you in the process?

YOUNG One thing that really surprised me is how ruthless I’ve been in pursuit of the music. And for how long I’ve been like that. I always knew I was callous—if I had to do something I had to do it, and I didn’t make any excuses. That might mean changing musicians midstream, or dropping a project to go somewhere else entirely. If that’s what I had to do to keep the songs coming then that’s what I did. But when I saw it, and I remembered what happened, and thought about how I dealt with things in immature ways, it gave me a lot of pause. But nonetheless, I continue on, and keep doing it anyway.

GW Why change now?

YOUNG [laughs] Yeah, right. Why change. So it’s good.

GW Something that became apparent to me was the incredible pace at which you were moving. To take just one span of time, say, mid 1968 through the end of 1969, you played your final show with Buffalo Springfield, released your first solo album, paired up with Crazy Horse for Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, began working on After the Gold Rush, joined Crosby, Stills & Nash, played Woodstock and cut Déjà Vu. That’s all in about 18 months or so.

YOUNG I was definitely doing a lot of multitasking. At one point I was recording with Crazy Horse in the mornings at Sunset Sound, cutting stuff like “I Believe In You,” “Oh Lonesome Me,” the original “Helpless,” “Wonderin’,” “Birds,” all kinds of things, and then in the afternoons I’d go play with CSN. And the only thing I really remember about that is that it bothered them that I was doing both things.

GW It bothered Crosby, Stills and Nash?

YOUNG Yeah, a little bit. But I liked playing with them, and I would always be there on time and ready to go. So I didn’t see a problem. But I was also playing with Crazy Horse. It wasn’t like I was gonna choose. Because playing with Crazy Horse brings a whole other thing out of me that never happens anywhere else. And that was maybe hard for them to understand. So it was busy, but it’s been really busy all the way through. Maybe in the last 10 years or so the pattern’s finally changing.

GW In what respect?

YOUNG There’s less waste now. I had massive amounts of waste all through the Seventies and Eighties. The most wasteful period is coming up in the next Archives.

GW Define “waste.”

YOUNG Things that were unfinished, things that never really got started, things that were finished and never used. There’s just so much music and nowhere to go with it.

GW What you characterize as waste is to some fans your most valued material—unreleased songs, out-of-print albums…

YOUNG That’s true. One thing I’ll tell you about the next volume of Archives is that Time Fades Away II is in there [the original Time Fades Away, a long out-of-print live album from 1973, is among the most soughtafter releases in Young’s catalog]. And it’s interesting, because the whole thing has a different drummer than what was on that album. I switched drummers halfway through the tour—Kenny Buttrey was in there for the first half, and Johnny Barbata came in for the second. It’s a completely different thing, with completely different songs. So that’s interesting. There’s lots of stuff like that that I’m working on right now for the second volume.

GW Among the many revelations on Archives is the wealth of material—recordings, photos, documents—of the Squires, the band you led in the mid Sixties while still living in Canada. While songs from this part of your career have been unearthed previously, this is by far the most complete picture fans have ever had of what was a pretty significant part of your development as a musician.

YOUNG The Squires was a very real thing. In one of the document folders on the first disc there’s a list that [bassist] Ken Koblun kept of all the shows we played. And it’s a lot of shows. I mean, that’s a band’s life right there. And Archives brings that into focus.

GW Overall, the material gathered on the first disc paints a picture of an artist in search of his own style. You move pretty rapidly from the instrumental surf-rock of the Squires to the Jimmy Reed–style blues of “Hello Lonely Woman” to a solo acoustic version of “Sugar Mountain,” which you cut as an audition for Elektra Records in 1965. That song would become one of the defining tunes of your early career, but on this version you sound very unlike yourself, as if you’re approximating what you believe a folksinger is supposed to be.

YOUNG That was probably what was going on. I was just trying to find who I was. And it was very uncomfortable for me to hear some of this stuff. In the case of “Sugar Mountain,” I couldn’t listen to it. I knew what it was and I listened a little bit but I just thought, God, that’s terrible. Because I can tell I was very nervous. I was just trying to be…something. But I didn’t know what it was.

GW At what point do you think that changed?

YOUNG When did it kind of consolidate into something real and I found some little bit of footing? I actually think there’s some showing of it earlier than the Elektra demos, on the Squires songs where I sing lead and that we cut for CJLX radio in Fort William in Ontario with [producer] Ray Dee. There’s two songs on the Archives from those sessions: “I’ll Love You Forever” and “I Wonder” [Young eventually reworked the latter song with Crazy Horse as “Don’t Cry No Tears” for his 1975 album, Zuma]. Those are both pretty good.

GW Speaking of your time in Canada, in a recent interview with Rolling Stone, Bob Dylan told a story of how, while on tour last year, he made a pilgrimage of sorts to the house in Winnipeg where you lived during the Squires days. He said he wanted to see your bedroom.

YOUNG I read that. Jack Harper, the original drummer for the Squires, sent me a copy of the article. It was a big deal in Winnipeg. That was remarkable.

GW Do you think he found what he was looking for?

YOUNG Absolutely. I’m sure he found it. I don’t know what it is, but I’m sure if I went to his house I’d find it there too.

GW Maybe you should go.

YOUNG I think I’d better. I’ve actually been through Hibbing [Minnesota, Dylan’s birthplace], but I’ve never been to Bob’s house. It might not even be there anymore. But there’s something to finding out where people came from. It’s interesting archival stuff. And you know, Bob’s a real musicologist. He’s a guy who could do something like Archives. I’m sure that he has his thing organized to some degree.

GW As far as your development as a songwriter and a guitar player, there’s some information to be gleaned from the versions of “Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere” that bookend the Topanga 1 (1968-1969) disc. The first one, from early 1968, was recorded with the backing musicians you used on the Neil Young album and is a breezy, acoustic take, accented by woodwind instruments. The version that closes out the disc, cut the following year with Crazy Horse, is in the ragged country-rock style you became known for with that band.

YOUNG Yeah that first one is very…organized. What’s going on there is the difference between recording in a very contrived manner and just playing with a band. One is built, the other just happens.

GW So with Crazy Horse it just “happened.”

YOUNG Well, I knew those guys. I knew them for a while, from back in Laurel Canyon, and I used to jam with them when I was still in the Springfield and they were still called the Rockets. And after doing that first solo record they were what I needed—I needed to play. I needed to go out and do things. I knew it was gonna be good with Crazy Horse. It was free.

GW Is that around the same time Old Black came into the picture?

YOUNG I think so. That’d be about then. I traded Messina for it. [As legend goes, former Buffalo Springfield bassist and producer Jim Messina, who also played on Young’s first solo album, gave up the 1953 Gibson Les Paul goldtop in exchange for one of Young’s Gretsch guitars.]

GW How essential was Old Black to the development of your guitar sound?

YOUNG I don’t know. I really don’t. I mean, that guitar was a different guitar then than it is now. It had a different treble pickup. The Firebird pickup went in after the first one got lost, and that happened a few years after we did Everybody Knows. The first pickup had a really bad buzz, and I sent the guitar to a shop to be fixed. When I went to get it, it was gone. And by that I mean the store was gone. The whole place just wasn’t there anymore. So that was the end of that. When I eventually got it back I tried a Gretsch pickup in there for a while, and then around the time of Zuma the Firebird went in. And that’s been the sound ever since.

GW People think of the Crazy Horse sound as this brute force, but the guitar interplay between you and [Crazy Horse guitarist and vocalist] Danny Whitten was actually a very nuanced and subtle thing.

YOUNG That’s exactly it. If you listen you can really hear how intricate it is, especially with the hi-def sound on the Blu-ray.

GW On “Cinnamon Girl,” to use just one example, your stylistic differences are more pronounced. You’re doing these voice-leading-type lines with a fairly dirty tone, while Danny has a much cleaner sound, and plays nice, ringing arpeggios across the neck.

YOUNG Danny’s tone was always much cleaner than mine. And what you’re hearing with the Blu-ray is basically the way it sounded to us in the studio. It’s almost as good as what we heard. It’s not quite as good, but it’s as good as it can be. Right now, at least.

GW What guitars did Danny use?

YOUNG He was playing a Gretsch most of the time.

GW Through any specific amp?

YOUNG Umm…Probably not. Probably just through one of my amps. Maybe a [Fender] Twin or a Bandmaster.

GW Did the two of you ever discuss what you were going to play, or work out your parts together?

YOUNG We never had to. We just started playing, and that’s what it sounded like. Danny was a great player. Phenomenal. And that part of Crazy Horse is now lost forever [Whitten died in 1972 from a heroin overdose]. The Crazy Horse that came along with Poncho [guitarist Frank “Poncho” Sampedro, who joined Crazy Horse three years after Whitten’s death] is a different band, and a completely different approach. You don’t hear that same interplay. You only get that on the things Danny was on.

GW On “Down By the River” you can hear how Danny continually alters his rhythm part behind your solos.

YOUNG It’s unbelievable. His work on that song is a masterpiece. The rhythm guitar position is a very powerful slot. You have to understand you’re part of an orchestra. You’re the backbone. You’re putting horn parts in. Opposition. Changing the groove. Every time you change the groove it changes what the lead guitar does. And with Danny and me it just happened. We never talked about any of it.

GW There’s great video on Archives of CSNY performing “Down By the River” on ABC-TV’s Music Scene, in 1969, and you and Stephen Stills are trading solos on a pair of big Gretsches. In terms of dynamic, how was playing with Danny different from playing with Stephen?

YOUNG Well, Stephen is a lead guitar player, but he can also be supportive. And Danny was a guitar player, and he was always supportive. He was totally confident in his role. Stephen and I are a little more competitive, in a brotherly kind of way. Then there’s the jacked-up part of CSN, which is the drums and bass aren’t as open. It’s more of a big deal. But the original is Crazy Horse. Everything else is just a version of that.

GW How would you evaluate Nils Lofgren, who joined you for After the Gold Rush?

YOUNG Nils I had known for a long time as a musician. I met him at the Cellar Door when he was 17. Then he came out to California and played on After the Gold Rush. He had a lot of energy—he practically walked from the airport to Topanga Canyon! And I just loved his guitar playing. When we’re matching up and playing dual guitars on “Tell Me Why” it’s fantastic. But he played too well to play with me. So for most of that album I put him on piano. He doesn’t play piano, but he was more challenged that way. It controlled all the extra playing, put everyone on the same level. Because I like to keep things simple.

GW With songs like “Down By the River” and “Cowgirl in the Sand,” which feature extended instrumental breaks, how many takes were cut in the studio?

YOUNG Maybe three or four overall, and the final version was usually an edited take. So, you know, maybe what you hear on the record would be take one, but with a couple pieces of something else in there. I could look it up. We have all the track sheets. All that information could be made available through Archives updates. We could make it so you could go in and figure out exactly what take you’re listening to of a specific song.

GW Archives features tons of great photos of you onstage with the Danny Whitten–led version of Crazy Horse, particularly on the Live at the Fillmore East 1970 disc. But one thing I noticed is that there’s no video footage of the band.

YOUNG That’s because we can’t find any, anywhere. But if people want it in the Archives it can be there. They just have to come up with the stuff. And also realize that once they get it to me it’s probably gonna be given away for free, but that doesn’t mean they lose it. It just means that I get the chance to duplicate it, create the best possible copy of it for mass distribution, and place it where it belongs in a timeline, with stories and information about what it is. That’s what I can do that would be hard for anybody else to do.

GW One thing you can’t be accused of is cherry picking the archival documents. There are some less than complimentary reviews scattered throughout the set, including one about a show at the Cellar Door that you read out loud in a video clip. The reviewer describes your onstage demeanor as being “as stimulating as watching your nails grow.”

YOUNG [laughs] I think it’s good to have that stuff there. When you see it in perspective it’s just as interesting as anything else. It’s a valid reaction. I mean, people wrote negative reviews about my Massey Hall concerts, because they were upset that I was playing songs that nobody knew. [For these shows Young debuted much of the material that would eventually make up the 1972 album Harvest.] What the fuck are you gonna do with that?

GW In that respect, the show documented on the Live at Massey Hall 1971 disc features what is in effect an embryonic version of what would become your biggest hit, “Heart of Gold.” Here, however, it’s merely a small piece of the song “A Man Needs a Maid.”

YOUNG Right. That’s the way it originally came out. It was just a little piano thing in the middle of a larger song.

GW How did it become its own composition?

YOUNG It just morphed. It grew. It’s interesting, because there’s another version of that song on Archives where I’m playing it live on acoustic. I put that version on there because that was the first time I ever used the harmonica onstage in front of people. But I have to think: did that version precede the recorded one?

GW Well, it appears in the track listing before the studio version.

YOUNG So then it happened before. That’s good to know, because I wasn’t playing the harmonica very good on that live take! It’s much better on the recorded version. And that’s probably why—it was later on. And you’re able to establish which came first because of the Archives. Things like that, as simple as they may be, they’re difficult to perceive without all the information laid out in front of you.

GW To bring up another instance of the Archives affording deeper insight into a song: On the Live at Massey Hall disc there’s a great video interview of you and your ranch hand, Louie Avila, shot at your Broken Arrow ranch in 1971. Even casual Neil Young fans tend to know that you wrote the song “Old Man” about Avila, but few have ever seen him or heard him speak before.

YOUNG And now you have. It’s like, “I believed that. But now I believe it.” It’s good to have evidence.

GW At one point in that video, the interviewer asks about the song “Old Man,” and Avila says something to the effect that it’s “really nice.” You sit there silently, and eventually say, “That’s really an amazing tape recorder you have there.”

YOUNG [laughs] That’s good.

GW Which reveals a greater truth about you that, in my opinion, has been displayed in countless interviews over the years: You don’t like to talk about specific songs, or the act of songwriting.

YOUNG It’s not really worth talking about, as far as I’m concerned. It’s so hard to nail down. It’s something that happens. It’s like breathing. It’s like a wind change or something.

GW But people do wonder about your process.

YOUNG Well, I can’t say what it is! Because it’s different for all the songs, and I can’t remember half of them anyway. They all have their own little story of how they came along, but I don’t know… I will say that the best ones come really fast. And they’re complete. There’s no editing or anything. You just get it.

GW In your introduction to “Mr. Soul” on the Sugar Mountain—Live at Canterbury House 1968 disc, you identify that song as one of the “fast” ones. You say it took five minutes to write.

YOUNG Yeah, that was one like that. And that’s how long it should take, about as long as it takes to write it down. So, I mean, what’s the process? The bottom line is there is no process. The process is, there it is.

GW How about your process as a guitar player? In particular, around the time of Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, were there other guitarists who influenced you as far as your pursuit of the louder, noisier side of the music? Jimi Hendrix would be an obvious point of reference, but anyone else?

YOUNG Not really. I mean, Jimi certainly. I liked him. He was on my radar. But not too many others. [Producer and occasional Young collaborator] Jack Nitzsche and I used to listen to the early Jimi Hendrix Experience 45s that came out of London before we did my first solo album. He was the latest, greatest thing from over there, and we were checking it out. Wanted to see what was going on.

GW What about any of the metal players? For example, you were getting pretty thick, detuned tones on songs like “Cinnamon Girl” and “When You Dance, I Can Really Love.” Were you aware of, say, Tony Iommi from Black Sabbath, another guy who tuned down his guitar?

YOUNG Not so much. But I love that music. It’s like classical rock and roll. The Scorpions, Iron Maiden… That whole thing is quite strong. It’s an art form in itself. That’s the thing about metal: some people think one band is great and another is just shit, while a normal person standing there couldn’t tell the difference between the two. So I was never a metalhead, but I’ll listen to a guy like Zakk Wylde play the guitar. And I know a lot of metal guys. They come to our shows because there’s something we do that I guess they connect with.

GW But there was nothing directly influencing you at the time you were first getting loud with Crazy Horse?

YOUNG Well, you know…when you really listen to it, Crazy Horse didn’t get very loud. Not until [1979’s] Rust Never Sleeps. The early Crazy Horse, with Danny, is not a big, whomp-’em, arena-rock sound. That happened with the second version of the band, when Poncho joined. “Cowgirl in the Sand” and “Down By the River”—when you listen to ’em, they’re not that loud. Though they can be, especially when we do them now.

GW Much of the “bigness” that’s associated with Crazy Horse, I suppose, is a result of the grit in the guitar tones, and also the space between the instruments.

YOUNG Yeah, there’s a lot of room in those records. Those songs were written to be explored forever. There’s no finished version.

GW How would you characterize your lead playing?

YOUNG It sucks! It’s just a fucking racket. I get totally lost when I’m playing guitar. I’ll just play a melody over and over again and change the tone, bend a string, do all that. I’m totally engrossed in what I’m doing. At one with it. But I suck. I’ve heard myself.

GW Some people would beg to differ.

YOUNG Well, I have moments where I really express myself on the guitar. But I can’t play acoustic like Bert Jansch, and I can’t play electric like Hendrix or J.J. Cale, who are probably the two best electric guitar players I’ve ever heard. And Jimmy Page, he’s a great one. I really love the way he plays. He’s so slippery. He’s very, very dangerous. Those are three classic guitar players to me.

GW What would you say are your strengths?

YOUNG I have melodies, and I have a sense of rhythm and drive. But it’s not about me, anyway—it’s about the whole band. It’s about everybody being there at once. When I play I’m listening for everything, trying to drive it all with my guitar. My guitar is the whole fucking band.

GW Perhaps an example of what you’re describing would be the famous “one-note” solo in “Cinnamon Girl,” which encompasses everything you’re talking about: lead, rhythm, melody, drive. Though my contention has always been that it’s not really one note…

YOUNG It’s not! Everyone says that, but there’s about a hundred notes in there. And every one of them is different. Every single one. They just happen to have the same name. [laughs]

GW Does it amuse you that people spend so much time evaluating the things you do?

YOUNG You know, I just thought I was playing the right solo. I mean, can you imagine anything else in there? Like, some fucking fast-note thing. Who needs that? It’s rhythm.

GW That said, is there any particular song or moment on Archives that really captures the essence of Neil Young as a musician?

YOUNG No one thing. No one thing. It’s too big. There’s too much information. And you can zero in as close as you like, but then you wind up going too far, and you gotta pull back out. It’s big-picture stuff. But it’s all there. You know, one day I’m gonna put out a download update, and when you open it up, there’ll just be several photographs of kitchen sinks. [laughs] That’s it.