The history of modded Marshalls

From master volumes to motherboards, we take a look at the evolution of Marshall mods with legendary amp guru Paul Rivera Sr

They say necessity is the mother of invention and so it was that during the late 60s and beyond repair shop engineers began to modify guitar amps to improve reliability and tone. Industry legend Paul Rivera Sr provides an insight into the pioneering years of the hot-rodder’s art

The appeal of early Marshall amps was their sonic transparency and response, not to mention the prodigious power of a 100-watt EL34 head plugged into a 4x12 Celestion-powered cabinet.

It was – and still is for many players – the archetypal rock guitar tone, a collision of components and voltages that created a unique voodoo. However, as guitarists grew into the new era of progressive rock powered by the likes of Jimi Hendrix and Cream-era Eric Clapton, the early Marshalls’ simplicity – and the unreliability of circuits pushed to the max – became more of a hindrance for some players, meaning there was a growing demand for modifications as well as repairs.

In the late 1960s and early 70s, the amp-modding industry hadn’t properly started, but amplifiers often needed repairing and it was repair shops that pioneered ideas in response to artist demands.

Early Marshalls such as the 1959 head were utilitarian clean powerhouses that only began to distort when turned up loud, at which point overworked power valves began arcing, so unsurprisingly many modifications were about improving reliability, besides adding more gain or controlling output power.

Later, as features such as preamp gain controls and master volumes became more common, they eventually filtered back into new factory designs, including the Mk2 and JCM800.

In the late 1960s and early 70s, it was repair shops that pioneered ideas in response to artist demands

Meanwhile, amp repairers were upping their games, especially in the USA. One of the original tone gurus and a founder member of an elite club of engineers responsible for kickstarting the amp modification and boutique amp industry is Paul Rivera.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Paul is well known for his association with Fender in the early 80s, but during his 70s tenure at the legendary Hollywood shop Valley Arts Guitars, and in the years prior, he worked on many Marshall amps. Paul Sr takes up the story...

Mods and rockers

“I cut my teeth on early Marshall amps at my first shop in NYC in the late 60s,” he tells us, “mostly warranty repair work, which gave me an opportunity to learn from the resident eastern European engineer who worked at their NYC distributor.

“Those early amps were temperamental due to excessively high anode and screen-grid voltages. Also, the output transformers were terribly stressed on peak-to-peak AC voltages due to the impedance swings of their speaker loads. Lots of blown output transformers and arced octal sockets!

Features such as built-in attenuators and automatic biasing started out on an independent amp designer’s desk

“A conversation in 1968 with a transformer engineer at Dynaco gave me hope that we’d found a superior output transformer and I started installing Dynaco’s A-431 in 50-watt models and the A-451 in 100-watt models. I soon realised that using the ultra-linear screen-grid taps would require a large filter choke to lower the ripple, so I kept the DC stock wiring.

“In hindsight, if Marshall’s Ken Bran had made a split DC supply with the screen grids kept at 50 per cent of the anode DCV, he could have had 600 volts on the anode and greatly increased reliability – based on using contemporary Mullard or Philips EL34s, of course. Those Dynaco transformers were far more reliable and sounded just magical.

“In 1972 I moved to Southern California, building my contacts in the music scene there. I continued developing Marshall modifications in stages to suit different budgets, helped by input and feedback from the studio engineers, producers and players that I worked with.

“This was about the same time that Marshall’s Mk2 amps arrived on the market, with substantially reduced DC voltages and greatly improved stability. As 6KV+ diodes became available in the 1970s, we were able to use them as ‘flyback’ diodes on the anodes, which effectively controlled the arcing and blown transformer issues.

“Most Marshall players loved the cranked tone but needed master volumes to make their amps useful in smaller venues. With a master volume, you could add extra gain without fear of deafening the first row of your audience – so that was Stage 1.

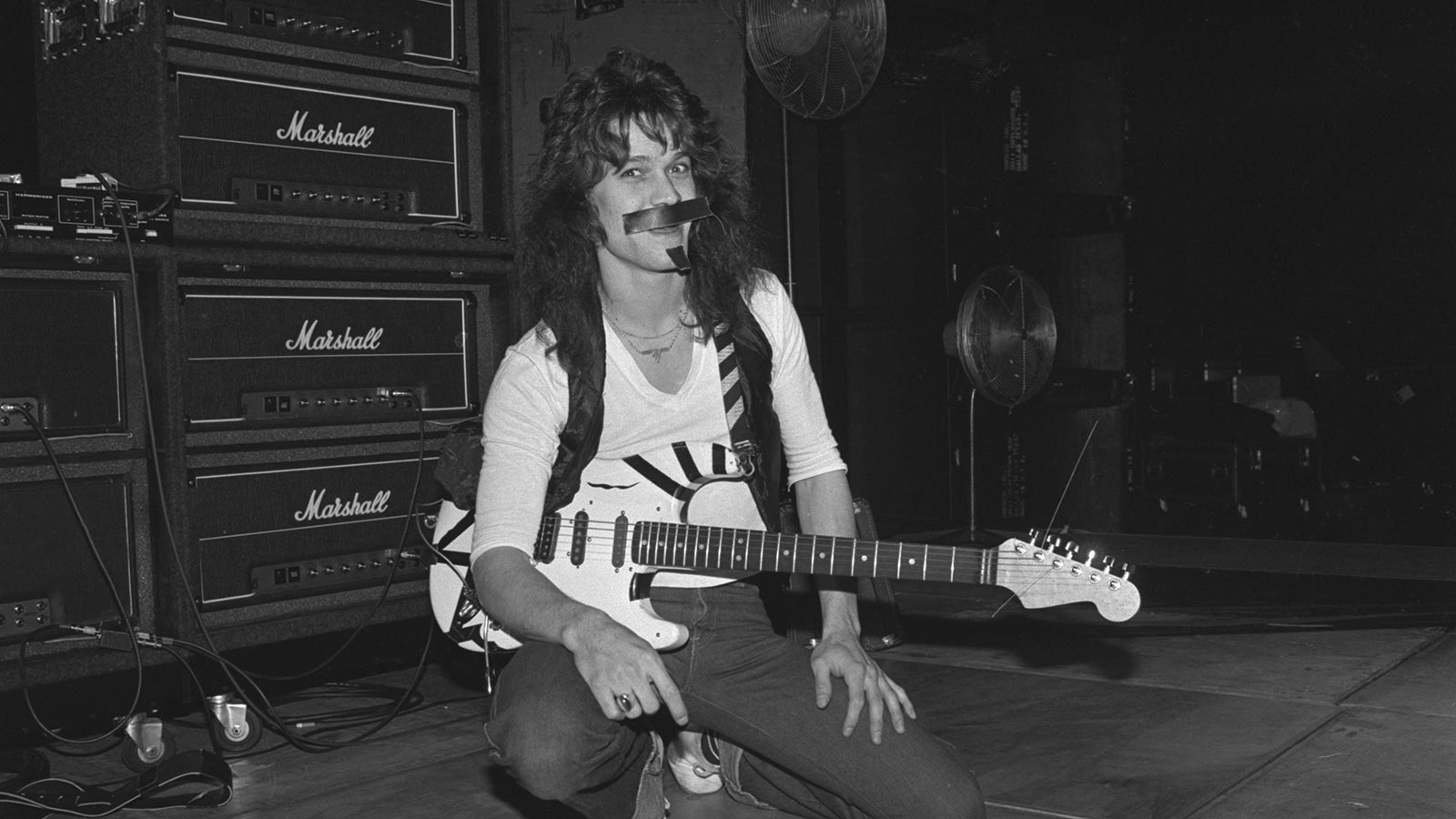

If you listen to Eddie Van Halen on Michael Jackson’s Beat It, that was a Stage 3 I did for a journalist who lent it to Eddie for the session

“Playing with the mids and bass frequencies, and creating a rotary switch to do all this, was part and parcel of the first Stage 2 mods. Master volume, switchable gain boost, a fat switch, an output stage rewire with flyback diodes (replacing the octal sockets if needed), and beefing up filter caps to reduce ripple and hum, all became Stage 2.

“Stage 3 added an additional preamp tube and associated circuitry along with all of the Stage 2 mods. An active effects loop was another option as time progressed.

“Stage 4 was full channel switching with two completely independent channels on a Marshall 1959 model, requiring dual-concentric potentiometers and stacked knobs to retain the stock appearance, additional preamp tubes, a bespoke motherboard PCB with Vactec (silent optical) switching, and a multi-function footswitch to control the effects loop bypass and channel switching.

“If you listen to Eddie Van Halen on Michael Jackson’s Beat It, that was a Stage 3 I did for a journalist who lent it to Eddie for the session. Most of Steve Lukather’ s tracks on the first four Toto albums were done using my modified Marshalls.

“Many other tracks by various musicians, including Eric Johnson, add to the legacy of those modified Marshalls I developed. So that was really the zenith. Post-Fender, by the time I started production of my own amps in late 1985, I had less time and desire to continue modifying other amp brands.”

A league of their own

Nearly five decades later, Paul Rivera is still as active as ever, recently completing a restoration on a flood-damaged Marshall Super Bass 100 now touring with Tool.

Other well-known Marshall hot-rodders who followed Rivera’s lead include Reinhold Bogner, who arrived in LA from Germany in 1989 and worked on amps for Steve Stevens and Jerry Cantrell before introducing his own designs. Lee Jackson of Metaltronix assisted the tones of Paul Gilbert and Steve Vai, and the late Jose Arredondo and César Díaz were both noted for their work with Stevie Ray Vaughan and Eric Clapton.

It’s an occupation that’s challenging for large and small manufacturers alike; sourcing components and subcontractors has become particularly difficult

These highly talented designers helped move the Marshall sound forward and shape the tones used by the next generation of players. Bogner’s three-channel Ecstasy made multi-channel heads the norm, while features such as built-in attenuators, automatic biasing and various other refinements all started out on an independent amp designer’s desk somewhere.

The USA amp hot-rodding scene in the early to mid-70s provided Rivera, Soldano, THD, Kendrick, Mesa/Boogie’s Randall Smith and many others with a platform to eventually manufacture and sell their own designs. Somehow, it never quite arrived in the UK.

While there’s no shortage of talent, most UK engineers tended to restrict themselves to servicing and repairs, with some ending up working for top brands including Marshall, while others such as Victory’s Martin Kidd and 633 Engineering’s Cliff Brown made the leap into manufacturing their own designs.

It’s an occupation that’s challenging for large and small manufacturers alike; sourcing components and subcontractors has become particularly difficult, with normally plentiful products such as diodes and capacitors now stretching out to 60-week-plus lead times.

Nevertheless, Marshall continues to evolve, with the current JVM flagships incorporating many features we now take for granted, often thanks to the past pioneering work of an army of hot-rodders.

Nick Guppy was Guitarist magazine's amp guru for over 20 years. He built his first valve amplifier at the age of 12 and bought, sold and restored many more, with a particular interest in Vox, Selmer, Orange and tweed-era Fenders, alongside Riveras and Mark Series Boogies. When wielding a guitar instead of soldering iron, he enjoyed a diverse musical career playing all over the UK, including occasional stints with theatre groups, orchestras and big bands as well as power trios and tributes. He passed away suddenly in April 2024, leaving a legacy of amplifier wisdom behind him.

"I never use my tube amp at home now, because I have a Spark Live": 5 reasons you should be picking up the Positive Grid Spark Live in the massive Guitar Month sale

“Our goal is to stay at the forefront of amplification innovation”: How Seymour Duncan set out to create the ultimate bass amp solution by pushing its PowerStage lineup to greater heights