Miki Berenyi details the songwriting tension that fueled Lush's landmark '90s releases and the twice-broken Gibson 12-string that helped define her sound

With the release of her new book, the early Britpop guitar icon reflects on her songwriting philosophy and reveals why she’s not bothered about taking vintage guitars on tour, despite her soundman's protests

British band Lush were part of the so-called “shoegaze” roster of early '90s bands, along with other outfits such as My Bloody Valentine, Ride and Chapterhouse. As with many genre offshoots, the groups involved perhaps shared an attitude rather than an overarching sonic philosophy, but nonetheless the scene birthed several classic albums, including Lush’s own 1992 shimmery dream pop LP, Spooky.

Originally formed in 1987 as The Baby Machines, Lush comprised vocalists/guitarists Miki Bereyni and Emma Anderson, drummer Chris Acland, and bassist Steve Rippon, whose place was eventually taken by Phil King. Garnering instant critical praise and a buzz with their first EP, Lush eventually released three full-length albums and won over fans with their engaging live shows, which included a stint on the second Lollapalooza tour. On record, Bereyni and Anderson’s breathy and plain-spoken vocals alternately wove together and bounced off one another, while the guitars chimed, jangled and droned.

The group disbanded in the mid-’90s after the death of Acland, and Bereyni took a long break from the music business before briefly reforming Lush in 2016. Soon after, she would join partner Moose McKillop in Piroshka along with members of Elastica and Modern English.

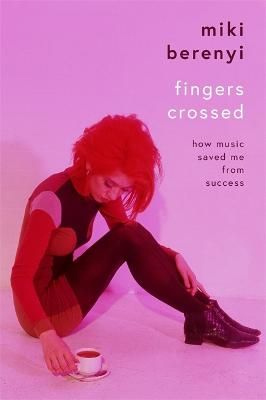

Her new autobiography, Fingers Crossed: How Music Saved Me From Success, covers her somewhat tumultuous upbringing, as well as her time in Lush, and is essential reading for anyone wanting a first-hand account of the British music scene just before Oasis battled Blur for the Britpop crown.

Guitar World caught up with Bereyni to discuss her memoir, her songwriting school of thought and her prized Gibson 12-string that had its neck broke not once, but twice.

What led you to write an autobiography at this time? Did you feel like anything was off limits?

“Basically, I was asked. I was approached by a publisher and initially I just wasn't interested at all. Then the magazine I worked for folded and the COVID-19 lockdown was looming and it wasn't a great time to be looking for a job. So, I actually did think, 'Right, I should probably give it a go, it's a good opportunity.' And I've got an archive of diaries and photo albums that are all annotated and there's quite a lot of letters.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I think when I started out it's exactly as you said: I thought, 'Well, what's off limits,' and, 'Do I go to these places?' I don't mind talking about things that are quite raw or problematic, as long as they come across in the proper context and with some sort of insight so it's not just unpleasant.

“The trickiest part was my relationship with Emma. You know, we don't talk anymore. It would've been an oversight to try and gloss over it. But, she's not happy about [the book]. I actually did pull back on quite a lot of stuff, mainly just things I wasn't sure that she'd be happy to have out there.

“That relationship… she would see it as that I've been very unfair about it, but I just think all the relationships in the book are quite viscerally described. It's not a complete character study. It's just my kind of pinball journey; the bits I saw of them and the bits that affected me.”

In the book you note that, for Emma, the most important thing was the songs. For you, was songwriting inherently tied up with being in a band and performing?

“Oh, definitely. I mean, it's like the book: I don't tend to have a clear idea of what I want to do until I'm in the middle of it, and it's usually someone else who is the catalyst. With the band, it was Emma who wanted to be in a band in which she was writing songs and we had that control, and I was required to write songs as well. It was like, 'Come on, we need to do a set and we've got to start playing gigs, so we need as many songs as we can get.' I think once we started recording it got a bit more selective and a bit more competitive, if I'm honest.

“It did mean that we wrote separately. We didn't go in and jam, and the bass parts weren’t handed over to either Chris or Phil to write. We wrote them ourselves. I thought that was a normal way to write songs, but I've since discovered that it isn't necessarily. But, I think the songs were the most important things and I think that's why, in a way, when we actually recorded them it was really the producer that would be the conduit for them.

“I got the impression that Emma didn't want me involved with her songs and that she wanted them done a certain way. That might be just my reading of it but that's the way I took it. And so, they were very separate, and I think the producer would be the person who was best equipped to say, 'I think this might need a keyboard part here.'”

When you were writing Lush songs, did you tend to start with a melody or did you have chord sequences or patterns that you gravitated to?

“I mean, it depends on the songs. A lot of the early ones like Baby Talk or Leaves Me Cold had a sort of noise element. Those songs started with the bass and the drums. It would be like, 'Okay, that's going to be the backbone of the song,' and then I'm just going to move whatever guitar chords work around that.

“A song like For Love was quite complicated. It's got that bassline that's quite hooky, but then to sort of build those chords around it a lot of that had to be tweaked and it had a lot of back-and-forth from the guitar to the bass, to the vocal, to the backing vocal. It took a lot of trial and error and a lot of building it up and changing it.

“Some songs literally would just start with the guitar and a vocal, and then I could just worry about the bass and drums later. But there were ones that I think had a really good bassline or a really good hook that I wanted to build it around. Certainly, the lead guitar, for most of them, was the last thing. That's just trim; fill in whatever you want. I think it was the last bit I would come to and find something that just fit with everything else that I'd written.”

On Lush albums, the guitars are not distinctly right and left channel, or lead and rhythm parts. They weave together and create intricate melodies. Did you and Emma work out those parts together?

“No, because one person would write the whole thing, even those guitar parts. Literally whoever's credited as the songwriter wrote the whole thing. All the parts, lyrics, everything. So, the only time I would get a credit on Emma's song is if I'd written the lyrics. I mean, you're right. We just had rhythm guitar. Neither of us was a virtuoso lead guitarist. Both of us started playing our instruments because we were in the band. It was literally like, work out a part and then learn to play it.

Limitations are sometimes good otherwise you sprawl out into trying to show off. The music has to work musically rather than around someone's ego

“It sort of restricts you, but I quite like certain restrictions. Limitations are sometimes good otherwise you kind of sprawl out into trying to show off. You know, we have nothing to show off, so it has to work musically rather than around someone's ego or ability.

“When we worked with Robin Guthrie [Cocteau Twins], that's kind of the way he produces. You might get a lot of shimmer and there might be a lead part that stands out but on the whole it's a sonic balance. The vocals are the same: not too far forward, everything sort of sits in and kind of comes out at different points. Then when the riff comes in it's right at the front again. You know, it's a different way of balancing that music.”

I was going to ask you about his production on Spooky. When you were recording the guitar parts, did you rely on pedals to sculpt the sound or was it developed at the mixing stage?

“To be honest, I've got like five pedals and they're the same ones that I had in 1990, so whatever mix comes out of those. Plus, my guitar is a 12-string, so you don't want to lose all of the actual 12-stringness of it. I think with Emma's stuff, it was more important to have lots of effects and Robin came up with a lot of that stuff.

“I think that's what I mean with the songwriting: it was the song that was key. It was like, if you came across a sound that worked that's it. I get that someone like Kevin [Shields] from My Bloody Valentine is the opposite of that. But you know, there's many ways to approach it.”

You mentioned your 12-string guitar, the Gibson ES-335. In the book, you briefly mention a Telecaster as your first guitar, but you spend more time discussing the vintage Jaguar you bought soon after.

“I wish I hadn't sold that Jaguar, because I do think it was a lovely guitar. It just wasn't right for what we were trying to do. The Telecaster was just something to learn on and Fenders have got a much thicker neck, and the action was so high on it I used to slice my fingers to ribbons. A lot of those vintage guitars I found so much easier to play. The Jaguar was easier to play, and then when I was looking at 12-strings the Gibsons have got a really slim neck.

“I've now got a Fender 12-string, which is lovely, but it's got a much thicker neck. It's trickier to actually manipulate around it. So, the Gibson 12-strings were perfect. I had a Rickenbacker twelve-string as well, which I did really like, but the strings are all the wrong way round, so it probably works better for lead than for rhythm. And it's a nightmare to string it as well.”

You mentioned in the book that one of Pearl Jam’s roadies accidentally knocked over the Gibson and broke the neck on the 1992 Lollapalooza tour.

“Do you know what? I had to cut various bits out the book just for space. That guitar neck first got broken when we toured with the Pale Saints in France. Someone kicked a football against it and it just went forward and hit the deck. It got repaired in Paris by a total craftsman. You just wouldn't be able to tell. It was beautiful and really, when it snapped, it was just destroyed. I thought, 'Well, that's it.' He fixed it. I was probably more sentimental about that guitar than any other and still am.

“And then when we went on Lollapalooza, it got knocked over again, and they sent it off and they got it fixed, but you can see the join, and it was nowhere near as well done. I think it was just the unfairness that got to me. It wasn't deliberate and they did their best, but Pearl Jam had like 50 guitars on stage and I've got like two in the whole world [laughs].”

Do you still have that guitar?

“I do still have that guitar. I was told it was a 1967, which is quite sweet because that's when I was born. I mean, I have no idea how much these guitars are worth or how special they are, because I just play them. I'm not actually that bothered. There's a Gibson Firebird I've got that my soundman is still saying, 'You have to leave me that in your will.' I'd take it on tour and he'd be having seizures about it saying, 'I really don't think you should be bringing this on tour.' And I'm like, 'Well, it's made to be played.'

In your book you discuss some of the sexual abuse you experienced growing up. Having that backstory helps the listener better understand some of your lyrics, but did you feel they were pretty straightforward in terms of subject matter when you wrote them such as on Kiss Chase?

“Yeah, I think it was important. I'd written lyrics that referred a bit to it on Tiny Smiles. That sort of hints at it, but it was a lot more cryptic. So, on Kiss Chase, you wouldn't have to dig too deep to figure out that there's something there. Even Hypocrite was very much about my relationships and promiscuity and that kind of stuff. I mean, Emma wrote When I Die on the album, which was about her father dying, so there was quite a lot of inward soul-searching stuff [on Split].

“Unfortunately, the album got mostly slagged off in Britain, and it kind of bruised me to reveal all that stuff and just have it dismissed as meaningless nonsense. I think with Lovelife, we kind of pulled back and I just thought, 'No, I'm not doing that again.'”

First-person songs don't have to be about personal experiences, but in your case, were they grounded in your own experience?

“Yeah, and I think that’s true even when you write about something that's inspired by a book. I think Covert was, for example. Emma bought me this Anais Nin book and it was about that, but it's about me really.

“I had enough bloody trouble trying to explain Ladykillers. It's meant to be a bit lighthearted. I'm not trying to crucify these people. It always annoyed me when people were going, 'Is that one about Anthony Kiedis?' And I'd go, 'All right, fine. It was inspired by that.' But blokes who say to me, 'Who's that about? Which particular person?' I think that kind of lets everyone else off the hook. It might have been inspired by a particular bloke, but there are an awful lot of blokes who behave like that.”

You mentioned the last Lush album, Lovelife. Many reviewers at the time commented on what they perceived as a change towards a more Britpop sound.

“I think we got quite a bit of grief musically for Lovelife, especially in America, because I think the shoegaze thing was much bigger. A lot of people thought we’d deliberately written a Britpop album. We ended up making that album with our soundman. You know, as much as I love working with producers, there was quite a lot of drama around Robin, and we knew Pete [Bartlett], our soundman, and he knew our sound, and it was all going to be simpler.

“And I'm not going to lie, [Britpop] was obviously part of the zeitgeist at the time – people weren't cloaking things in layers and shimmers and God knows what. It was quite liberating to be able to just try that.

“I do still defend it. Split had Hypocrite on it and that is not a shoegaze-y song. I don't see that massive leap from those songs to where the hits on Lovelife came from. I think people just thought oh, you've cynically sat down and gone, 'Right. We're going to ditch the shoegaze thing and we're going to completely reinvent ourselves.' I'm not sure most people do that. I think someone who writes songs for other people might do that. But with a band, it is quite organic.”

You took a bit of a break from the music business after Lush broke up in the 1990s before briefly reuniting in 2016. Your new group Piroshka has released a couple of albums. Are you working on new material?

“Yes. We will be writing, but this book has taken up such an inordinate amount of my time that I haven't had time to sit down and write music. And it's quite a tricky band because one of the members got married and is living in America, so I don't even know how this is going to work with the next album. And Justin [Welch] does a lot of touring with The Jesus and Mary Chain. Hopefully soon we’ll just be able to knuckle down and start writing.

“After Lush and before 2016 I didn't do any music. I barely picked up a guitar. I did the odd vocal that someone would ask for. But Piroshka formed because Justin thought it was a shame to end Lush and not do something afterwards. That's how that started. When Chris died it was like a grenade going off: I just had to run in the opposite direction and music didn't have any appeal for me.

“I really needed to get away, and working and having children; it was great to just put all my energies into something else. I didn't even miss it and it wasn't until we did the reunion, we had to rehearse and we were playing, it sort of came to me how much fun it is and how brilliant it feels. You do look at people wide-eyed. I don't want to say it's orgasmic, but you know, it's a bit like looking at someone and going, 'Hell, that was amazing, wasn't it?'

- Fingers Crossed: How Music Saved Me From Success is available now.

Bruce is a freelance writer of features and interviews for Guitar World and MAGNET Magazine among other titles. He's played guitar in numerous garage bands with much better musicians who sometimes laugh at his Ovation Breadwinner.

Guitar World Discussion: Who is the most underrated guitar player of all time?

Ozzy Osbourne’s solo band has long been a proving ground for metal’s most outstanding players. From Randy Rhoads to Zakk Wylde, via Brad Gillis and Gus G, here are all the players – and nearly players – in the Osbourne saga