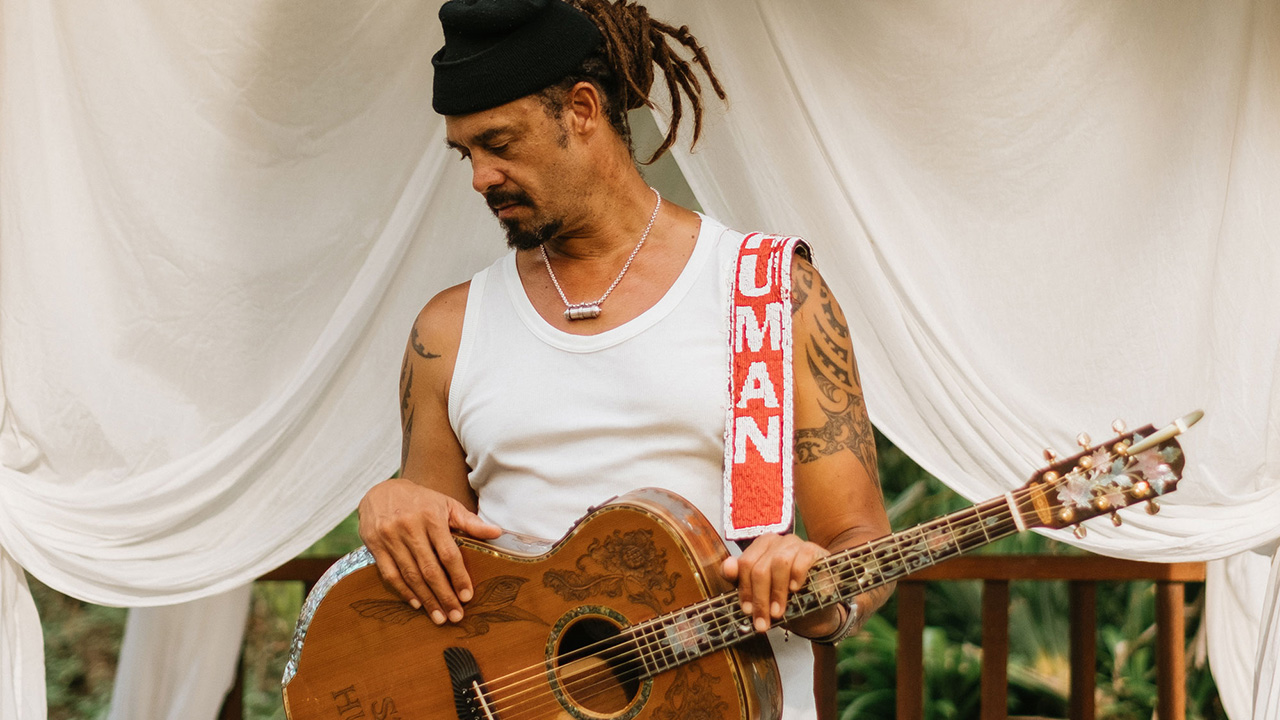

“The guitar is a metaphor for so many things that happen in life. When your life is completely out of balance, you have to find ways you can retune it”: How Michael Franti fought back the darkness with a 25-year-old acoustic named after his grandma

The Spearhead leader explains why it’s not just the sound of the guitar that soothes him – it’s the vibrations as well

This article is part of Guitar World's series of interviews and features with artists addressing and raising awareness around themes of mental health, particularly as they relate to musicians.

For over 30 years Michael Franti has dedicated himself to music, activism and philanthropy. His passion takes him around the world with his longtime band, Spearhead, spreading joy through songs and working toward social justice and positive change.

Like billions of others, Franti’s world turned upside down during the Covid pandemic. Lockdowns closed the Bali hotel he owns with his wife, where he resides when not on the road. In April 2021, while she was away, Covid took his biological father – a man he’d not met until he was 22, and with whom he’d shared a complicated relationship.

At home with his youngest son, Taj, Franti spiraled into grief and depression. He was isolated, far from friends and loved ones, and distant from the thing he needed most: the community of live music.

Later, an outdoor concert by Balinese band The Munchies became the first show Franti attended in two years. The experience was pivotal, allowing him to finally free long-suppressed emotions, and start working on his mental health.

When everything came to a stop during lockdowns, in the midst of your grief, how did you maintain your music lifeline?

“In a matter of months, my wife and I lost every bit of savings we had. The music industry and tourism shut down. But more than losing my living, I lost the thing I love more than anything, which is bringing people together and sharing big emotions through music. When I wasn’t able to do that, I lost a sense of myself and who I am in the world.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“When I got Covid and spent a week in a room by myself, I started writing songs. I wrote one called Trying to Keep the Lights On, which was about our house and our business, but also about trying to keep the lights on in my heart – that glow, that spark of optimism. The more I wrote and sang the words, the more it helped me. I would sit and cry to my own song.”

How dark was the darkness at your lowest?

“I felt hopeless. My wife and I had lost everything. Two of my family members – an uncle and my biological father – died of Covid. I was in a dark place and not seeing a way out. The thing that really shook me was seeing other musicians I knew who had taken their own lives and how I empathized with them.

“I was like, ‘I totally get it. I understand that feeling.’ I saw the pain of their families, the people who loved them, and people who cared about their music. Through conversations with my manager and my wife I worked out, ‘I need to find outside help to get through this.’”

I was laughing, shouting, crying… I needed to have music flushed through me in that way.

You credit The Munchies with reconnecting you to music and yourself. What was that moment like?

“They were having so much fun and sharing so much joy. I was dancing with Taj, my little guy, and at one point the music really kicked in. I closed my eyes, put my hands up to the sky, and tears started streaming down my cheeks.

“I was laughing, shouting, crying, dancing, screaming, shaking and sweating. After about an hour I felt better. I needed to have music flushed through me in that way.

“I wrote Hands Up To The Sky (Big, Big Love) about the moments in our lives when we need to throw our hands up, feel the release of letting go and say, ‘I’m just going to throw this out to the universe.’”

Many people point to your music as therapy, and you’ve often said music is therapy for you as well. In addition to songwriting, how does performing live help you?

“One of the beautiful things about being a songwriter is I write from my places of deepest emotion, whether it’s sadness and pain or joy and elation. Then I go out onstage and perform it, and I see people who need the feeling I had when I saw The Munchies play. They walk out a little bit taller than when they came in.

“That, for me, is the reward in all of this – seeing how something you felt really deeply lands on somebody else. Because in those times when I feel it, I often feel like I’m the only person in the world who maybe feels this way. It’s comforting to know I’m not.”

I recall an interview in which you said that sometimes just sitting and strumming a guitar is a source of comfort.

“This might seem funny to people who enjoy listening to guitar, but I play it because I enjoy not just figuring out the fingering, but the actual sound of the guitar against my body – the vibrations coming through it into my body and into the air and through my ears. It’s comforting to me.

it’s important to look into the eyes of a stranger and go, ‘I see you, I get you, I understand you’

“I play a Maton that I’ve had for over 25 years. I have other guitars, but they’re backups in case I break a string. The Maton is named Mama Brown, after my grandma, who worked as a domestic house cleaner until she was in her ’90s, and always remained an optimist.

“She had a way of making people feel at ease, whether through her humor, playing piano in her living room, or reading her old folded-leaf Bible that had a million notes in it. She just had this way. I hope my guitar can be that for other people. That’s why I named it after her.”

Is playing guitar as big a part as writing and singing when it comes to expressing deep emotions?

“The guitar is a metaphor for so many things that happen in life. When your life is completely out of balance, it’s like you have to find ways that you can retune it – retune that instrument, and get in there and really play.

“You have to find ways you can practice so that when you do go into those dark spaces, you’ve prepared methods of getting out of them ahead of time, and they’re accessible to you.

“The guitar is such a part of my life. Before the shows we do meet-ups in the parking lot or wherever. I always bring my guitar. As soon as we start to play with a group of people in that space, the energy is created. It’s the same as when I then go play for thousands of people onstage. It’s music and guitars. They’re magical healers – magical beings.

“I think guitar players will understand when I say that playing guitar often creates solitude; sometimes it’s chosen and sometimes it’s loneliness. Choosing it is good, but loneliness can eat at us. To all the guitar players out there, I hope your playing leads you to a path of deeper connections and not feeling alone.”

Take us back to when you were able to play live again.

“I remember walking onstage at Red Rocks Amphitheater in front of 10,000 people. The first thing I felt was this incredible sense that, for two years, we couldn’t be in the same place together; and now here we are, and it’s important to look into the eyes of a stranger and go, ‘I see you, I get you, I understand you.’

“The second thing was incredible gratitude. I never, in all my decades of making music, would have imagined that a virus would stop us. To be able to play again, I had this deep sense of gratitude; and then the great feeling of release: ‘I’m here, I’m playing music, and I can finally feel that freedom and optimism.’”

- Michael Franti & Spearhead’s latest album Big Big Love is out now. They’re currently touring North America.

Mental health resources

Alison Richter is a seasoned journalist who interviews musicians, producers, engineers, and other industry professionals, and covers mental health issues for GuitarWorld.com. Writing credits include a wide range of publications, including GuitarWorld.com, MusicRadar.com, Bass Player, TNAG Connoisseur, Reverb, Music Industry News, Acoustic, Drummer, Guitar.com, Gearphoria, She Shreds, Guitar Girl, and Collectible Guitar.