Metallica: Monster's Brawl

Originally published in Guitar World, June 2004

Fights! Camera! Action! What started as a simple documentary about

Metallica nearly became an account of the group’s destruction. Guitar World goes behind the scenes of Metallica’s critically acclaimed movie, Some Kind of Monster, for a scorching blow-by-blow report.

There’s a scene that occurs roughly an hour into Metallica: Some Kind of Monster, the band’s intense new documentary. Drummer Lars Ulrich, pacing the floor at the band’s HQ studios in San Rafael, California, looks across the room at singer and guitarist James Hetfield, fresh out of rehab and still struggling to readjust to the outside world, and offers him a comforting welcome home. “When I was running this morning,” says Ulrich, “I was thinking about seeing you today, and the word fuck just [came] up so much.”

Hetfield, who had been nestled away in a rehabilitation center for more than six months battling alcohol addiction and various other life-afflicting demons, sits silently as Ulrich begins repeating the word, mantralike.

“Fuck,” he snarls at the man with whom, more than 20 years ago, he cofounded what is arguably the most successful heavy metal band in history. “Fuck!” Finally, Ulrich moves in close, until the two are practically nose to nose, and screams one last time: “Fuck!”

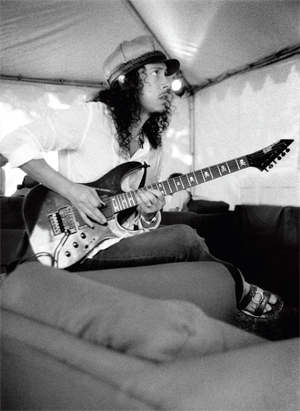

It’s a particularly intense and ugly moment in a film that has no shortage of either. Some Kind of Monster tracks Metallica from the sudden departure of bassist Jason Newsted in January 2001 to the completion of their eighth studio album, St. Anger, more than two years later. Throughout the two-hour-and-twenty-minute film, which will be theatrically released in summer 2004, the actions of Metallica’s core members—Hetfield, Ulrich and guitarist Kirk Hammett—are sometimes petty, sometimes reprehensible and occasionally downright embarrassing. And that’s exactly what makes the documentary such a riveting piece of work. Equally impressive is the fact that Metallica, who have been practicing rigorous damage control on their image for nearly a decade, wholeheartedly endorsed being shown in such a revealing and often negative light.

“Our attitude from the beginning was ‘warts and all,’ ” says Hammett. “We said to [filmmakers] Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, ‘Show us good, show us bad. Just show us.’ And you know, sometimes we look like assholes and sometimes we look like spoiled rock stars—but we also look like human beings. I think presenting the full picture offers more insight into who we are as people.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“There’s still a little part of me that fears this film will come out and people will actually go to see it,” says Hetfield. “But then there’s another part of me that thinks, Hell yeah, people are going to see your struggles, they’re going to see your high points and your low points and they’re going to get to know you better. And that’s exciting.”

By now it’s common knowledge that Metallica went through a rough period prior to St. Anger’s release in June 2003. The media coverage that accompanied the album’s release often—and rightly— characterized the band’s previous few years as a perpetual downhill slide that began when Ulrich crusaded against Napster and subsequently alienated the band’s core fan base, continued when Newsted jumped ship after 15 years of service, and bottomed out when Hetfield entered rehab for “alcoholism and other undisclosed addictions.”

What was given short shrift, however, was how hard the band’s members fought—as a unit and against one another—to survive each new tragedy that befell them. Their efforts included hiring a $40,000-per-week “performance enhancement coach” named Phil Towle (a move that in the film Newsted dismisses as “really fucking lame and weak”) and overhauling their infamously rigid working conditions to allow each band member equal say in the songwriting process. And as the film demonstrates, Metallica struggled not only to move forward but also to confront head-on the issues that had hindered them in the past. This is no more evident than when Ulrich sits down for a one-on-one, long-overdue meeting with former Metallica and Megadeth guitarist Dave Mustaine, who was brutally fired by Ulrich and Hetfield in 1983.

“This is not a movie about the making of St. Anger,” says Hetfield. “It’s not about the music. This is a movie about the people in Metallica and the relationships that they share with one another and with the other individuals in their lives. The music is secondary to the whole picture.”

“Hopefully,” Hammett adds, “by showing what we went through, the film can give some direction to other people that are experiencing some of the same things, whether they’re in a band or not. I think that we explored options that a lot of other bands wouldn’t have even considered. And yeah, I know Metallica have an image as this big, indestructible entity and that a lot of the things you see in the film, like us sitting in therapy, may be viewed as signs of weakness. But I gotta tell you, we’ve always been known for just laying our balls on the line and saying, ‘Fuck it.’ ”

Over the years, that tendency has resulted in the band receiving more than its fair share of criticism, and many of the scenes in Some Kind of Monster will only inspire more such attacks. Anyone who has written off the band’s post–Black Album career as nothing more than an across-the-board sell-out bid for mainstream acceptance will only have those feelings justified watching as James, Kirk and Lars begrudgingly record an ass-kissing promo spot for a radio station contest. Similarly, Ulrich’s post-Napster image as an arrogant, money-grubbing aristocrat is blown up to almost parodic proportions in one scene filmed at a swanky New York City auction house. As his pricey art collection is sold off for millions of dollars, the drummer sits in a private room, gleefully sipping champagne while an orchestral version of “Master of Puppets” plays softly in the background.

But moments like these are the film’s essence. Some Kind of Monster isn’t meant to be a glossed-over, Behind the Music–style infomercial disguised as an exposé; it’s more akin to pulling back the curtain on the Wizard of Oz and finding that, far from being all powerful, he’s quite human, vulnerable and flawed. And that’s where Metallica, for all the “warts” exposed, are most successful. Love them or hate them, you cannot deny that their careers have had more than their fair share of trailblazing, uncompromising and inspiring moments. Some Kind of Monster is simply yet another triumph.

And the whole thing almost never happened.

When Metallica first met with Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky to discuss working together, the band was, in fact, interested in a promotional tool that could help sell a new album. The group had struck up a relationship with Berlinger and Sinofsky while the pair were working on Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills, their 1996 documentary about the trial of three heavy metal–loving teens convicted of murdering three young boys in West Memphis, Arkansas, in 1993. In the film, Berlinger and Sinofsky argued that the boys’ affinity for wearing black clothing and listening to metal was ludicrously inadequate proof of their guilt. They had hoped to license several Metallica songs to use in the project, and had faxed what they thought would be a futile request to Q-Prime, the band’s management.

“At the time, Metallica had never granted the rights to let their music be used in a movie,” says Berlinger, “and we figured that even if they did, they would charge a lot of money for it. But we got a callback an hour after we sent the fax and it was like, ‘Sure, what songs do you want?’ Apparently, the band were big fans of our first film, [1992’s] Brother’s Keeper, and they liked what we were doing with Paradise Lost. And to top it off, they gave us the music for free, no strings attached. And that’s how our friendship began.”

Despite numerous discussions over the ensuing years about a full-blown collaboration between the two parties, the closest they came to working together was when Berlinger and Sinofsky produced a Metallica episode of the short-lived VH-1 series Fan-Club. “Other than that, the whole idea died,” says Berlinger, “because we hit an impasse. Bruce and I wanted to do a film that took a very personal look at the band, while management had more of a clips-driven, historical thing in mind that they could run on an HBO or an MTV to help them sell product.”

It wasn’t until the end of 2000 that the idea was revived. At the time, Berlinger was reeling from the critical lambasting of his big-budget Hollywood directorial debut, Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, a movie whose failure he blames on the studio “basically putting my cut into a blender and puking it out into the theater.” Berlinger thought it might be therapeutic to resurrect the Metallica project. To his surprise, management responded to his new inquiry with the news that Jason Newsted had just quit the band, Metallica were about to begin recording a new album with producer Bob Rock handling bass duties, and all the members, including Rock, were taking part in group therapy sessions. How would he and Bruce like to film the whole thing?

“It was like being dropped into Vietnam during the war without any preparation, and all of a sudden you’re right there in the thick of it,” says Sinofsky. “And there were no handlers or managers saying, ‘You can’t do this’ or ‘You can’t do that.’ It was just like, boom!—a month or two after the first phone call we’re filming a therapy session. I remember Joe and I looking at each other during those first few shoots and thinking, We don’t know where this is going, but it’s going to be unbelievable.”

“A film like this you can’t really plan out,” says Hetfield, “like, ‘Hey, let’s start rolling tape, and maybe something traumatic will happen soon!’ But things did start happening, and Joe and Bruce were there to capture these pivotal points in our personal history, which we then had an opportunity to share with the world. And if those things hadn’t happened, we would have merely had an ‘in the studio’ type of film that would have been used as promo material.”

As filming dragged on for more than a year—a time period that included a long and dormant stretch during which Hetfield was away in rehab—the project came dangerously close to being turned into a promotional vehicle. Elektra, Metallica’s record label, was anxious to reap benefits from its investment and pressured the filmmakers to wrap production. The label hoped to fashion a block of reality TV–like segments from the raw footage and air them to coincide with the release of St. Anger. But Metallica, believing the film had the potential to tell a much bigger story, opted to buy out their label’s 50 percent share of ownership (at a price of $2 million) and allow Berlinger and Sinofsky to complete the project as they saw fit.

Although Hetfield, Hammett and Ulrich are now the sole owners of Some Kind of Monster, it’s apparent from the final cut, culled from more than 1,600 hours of footage, that they didn’t place any constraints on the directors. Berlinger, for one, believes that is precisely what makes the film so impressive. “If these guys didn’t have complete control over the movie and weren’t paying for it out of their own pockets, it wouldn’t be as remarkable. The things you see wouldn’t have the same impact if Bruce and I were just two independent newsmen who dug up some dirt on the band and shoved it into a movie. Metallica could have told us to take out anything that they decided they didn’t want the public to see, but they treated us as if we had final cut. There’s absolutely nothing that they kept out of the film.”

“I’ll tell you,” adds Sinofsky, “if I were Lars, James or Kirk, there are certainly moments in the film that I would’ve demanded to have deleted. That art auction scene? Lars was pressured to take it out by many people in the band’s inner circle—from wives to managers to lawyers—who all told him that it’s no good for his image. And to Lars’ credit, he was like, ‘Fuck it! This is who I am.’ And you have to have respect for that.”

While Metallica and the filmmakers say they weren’t interested in having Some Kind of Monster function merely as a promotional tool for St. Anger, in some indirect ways it does just that. Upon the album’s release last year, many fans put off by its minimalist song structures and raw production accused the band of lacking the passion and commitment that had always characterized its best work. But it’s evident in the film that, for Metallica, creating St. Anger was more than a labor of love—it was literally hard labor, requiring more dedication and determination than perhaps any record in their career.

Throughout the film, the band members—in particular Ulrich and Hetfield—battle over riffs, drum beats and lyrics, and break out of their strictly defined musical roles to help one another with their parts. (The lyrical hook “My lifestyle determines my death style” from “Frantic” is revealed to be not a Hetfield-composed rehab mantra but rather one of Hammett’s Zen-like axioms.) Furthermore, the first section of the film is littered with recorded attempts at songs that didn’t make the final cut of St.Anger. One tune, in which Hetfield repeatedly sings the word “temptation,” is built on a slow, doomy riff and a tom-heavy drumbeat that sounds like nothing else in Metallica’s recorded history.

“If we didn’t go through those songs, we wouldn’t have made it to the ones on St. Anger,” says Hetfield. “They were like stepping stones. There’s some pretty diverse music in there, just a mix of a lot of different things we tried. We wanted to explore every possibility.”

Some Kind of Monster also lends greater insight to the album’s lyrics, which typically have been interpreted in terms of Hetfield’ rehab experience. Many of the songs do address issues the singer dealt with during that period, but it’s not the only subject confronted. The film reveals that “Shoot Me Again”—with its refrain, “All the shots I take/I spit back at you”—is about Ulrich’s fight with Napster and the criticism he endured over it, while the opening line of “Sweet Amber”—“Wash your back so you won’t stab mine”—is a phrase uttered by a disgusted Hetfield after he’s informed that Metallica’s refusal to record the radio promo spot could result in their being blacklisted by the large conglomerate that owns the station.

And then there’s “My World,” a song that could almost be a group catharsis. In one of the documentary’s final scenes, the band is shown jamming the song, whose lyrics deal with regaining control over one’s own life. St. Anger has been completed, new bassist Robert Trujillo has joined the fold, and Metallica, once again functioning as a complete unit, are preparing to go out on tour. It’s at this point the group decides to give Towle his walking papers. The therapist has become too close to the group; he’s even attempted to contribute lyrics to St. Anger’s songs. (Earlier in the film Hetfield remarks that Towle is “under the impression that he’s, like, in the band.”) The band meets with Towle and effectively ends their working relationship. Afterward, Hetfield is shown singing the opening line to “My World,” “Who’s in charge of my head today?”

“When I came out of rehab I was like raw hamburger,” Hetfield explains. “Anyone could have shaped me into anything they wanted. So when Phil started doing things like handing me lyrics to sing, it was like, ‘Well, this feels weird, but am I being too rigid? Maybe I need to accept things and open up more.’ I didn’t know where the boundaries were. At some point it became obvious to me that I was totally confused as to where the business part ended and the friendship began. And it seemed to fluctuate whenever Phil needed it to.”

“But,” adds Hammett, “he also really helped us accomplish what we needed to get done. It was just that, toward the end, things started to go a little haywire.”

“I believe that the band is together today because of Phil,” says Berlinger. “And yeah, he got a little too close, but I don’t think that was a bad thing, because for Metallica the final stage of the program was to push him away. Part of the growth process is that children need to flee the coop.”

One particular therapy session that fans will be anxious to see occurs when Ulrich sits down with Dave Mustaine to talk at length, and possibly for the first time, about Mustaine’s firing from Metallica in 1983 due to his hard-partying ways, and about the effect the dismissal has had on his life. As Ulrich sits in near silence, his eyes watery and often focused on the floor, Mustaine describes the pain of having to watch, as he describes it, “everything that you guys do…turn to gold, and everything I do fucking backfire.” It’s an intensely revealing scene that lends a human touch to a story that, over the years, has become a part of heavy metal folklore. While he places the blame for his ouster squarely on his own shoulders, Mustaine takes Ulrich to task for the hostile way in which it was handled, noting that, unlike Hetfield, he was never given the option of attending rehab, and how, over the years, neither Lars nor James had made a genuine attempt at reconciliation.

Mustaine has since made it known that he is unhappy with his portrayal in the film, and although he declined to comment for this story, this past January he posted a cryptic message on Megadeth’s official web site in which he wrote the movie off as “Some kind of bullshit,” and stated, “I noticed how much footage they used [of the meeting] and to whom it benefited, too.” Berlinger and Sinofsky, for their part, are confused by Mustaine’s reaction.

“My experience with Dave was that he was a real gentleman,” says Berlinger. “I know that when he showed up he was a little surprised to see the cameras, but I explained to him what we were doing, and he signed a release form giving us permission to use the footage. The whole meeting between him and Lars lasted about two or three hours, and we turned off the cameras three times, at his request, when things got a little too emotional. We tried to be very respectful of his feelings.”

“Here’s a case where the truth shouldn’t hurt,” says Sinofsky. “The Metallica and Megadeth fans who see this film will probably get a better understanding of Dave Mustaine than they have in 20 years.”

“The guys in the band are aware that Dave isn’t happy with that scene,” says Hammett. “But he said what he wanted to say, and nobody put any words in his mouth. Dave had free reign to present himself however he wanted to. And if he feels now that he didn’t present himself in the proper way, is that really our fault?”

For all the focus on relationships in the film—be it Mustaine coming face-to-face with his former band mate or a bunch of heavy metal he-men sitting around discussing their feelings with a middle-aged, bespectacled therapist—one relationship in particular is clearly at the center of Some Kind of Monster: that of James Hetfield and Lars Ulrich, the two men who were there when Metallica began, and who will be there, for better or worse, when they end. What the movie makes apparent is that the band’s demise was actually a lot closer than perhaps anyone realized. Berlinger admits that there was a point during the filming where he and Sinofsky “were pretty sure that we were making a documentary about the disintegration of a band.” After one particularly nasty scene in which Hetfield and Ulrich argue over the latter’s choice of drumbeat for a song, Hetfield storms out of the room and doesn’t return—for months. It was during this time that he checked himself into rehab and cut off all contact with the rest of the band.

“It really felt like there was no future for Metallica,” says Hammett. “I had to start thinking about backup plans, like, Maybe I should make a solo album, or maybe I should start raising horses.”

“In all honesty I wasn’t sure if I was going to come back,” admits Hetfield. “And that was needed in order for me to come back in a healthy way. I had to ask myself, ‘Who am I?’ I have to walk around with the idea that people have pumped into my head that, ‘Hey, you’re the dude in Metallica. That is your worth. If you’re just a person on your own you’re not worth as much.’ Which is total crap. I had to realize that I could live without the band in order to live with it again. And I think that was scary for Lars, because I came back to the band as a different person, and it’s tough when someone else’s changes in their life begin to affect your own. Especially when the two people involved are both egocentric control freaks!”

Hetfield delivers that last statement with a laugh, but it’s clear that there is also some truth to his words. Which raises an interesting question: Is friction between great egos a necessary ingredient for all successful creative partnerships? Were the notorious clashes between legendary duos like John Lennon and Paul McCartney, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards and Steven Tyler and Joe Perry in part responsible for them creating some of rock and roll’s most enduring music? According to Hetfield, the answer is not quite so clear.

“That friction does help in some instances, but I don’t think it’s absolutely necessary. Because you see some musical writing teams that get along great, and even some that are husband and wife, and you think, My God, how can they work together and live together? But they do, because different people work off of different energies. In the case of Lars and I, we worked a lot of the time off of negative energy and also off of perfectionism. We were the kings of pushing each other further—like, Hey, to make this better I’m gonna drill you! As a result, there was this atmosphere of, Okay, I know he’s gonna say this, so I’ve gotta get my armor on, and then retaliate this way—just a lot of fear and defensiveness. But we’ve come to understand that it doesn’t have to be that way. We each have really clear and excellent visions of what music is for us, and we can realize those visions without making the other guy suffer.”

Hammett, for his part, states in the film that he forever tries “to be an example of being egoless to the other guys.” Throughout Some Kind of Monster he’s constantly playing the role of mediator between Hetfield and Ulrich, attempting to keep things running smoothly so that the band can continue working. “Egos create gridlock,” reasons Hammett. “If I started in as well, there would just be three egos battling instead of two.”

pushing to that next level. James is clearly“In the film, Kirk is always the guy saying, ‘Come on, let’s not beat on each other,’ ” says Sinofsky, “while Lars is constantly the one with the most problems, and his story is so inspirational because he’s willing and able to overcome those problems. I have so much respect for all of the guys, not only for what they were willing to go through to save their band but also for having the guts to let us film it and now to show it to the world.”

Fans may view Some Kind of Monster as a heroic epic, cautionary tale or merely voyeuristic, reality TV–type fodder. What’s certain is that, for the members of Metallica, at least, the film contains many important lessons that they will continue to learn from in the years to come.

“Cliff Burnstein [Metallica’s manager] was asked what he thought the value of Some Kind of Monster will be,” says Berlinger, “and he said, ‘Forget about the publicity or if it’s going to make money or help to sell some albums—forget about all of that. The most significant thing the film is going to do for these guys is that when things start to fall apart two, three, 10 years from now, I’m going to sit them all down and make them watch it again. It will be a very important vehicle to remind them of what their relationships can be about.’ ”

“That’s a really cool way to look at it,” says Hammett. “This film can be a lesson for the future that was created in the past—sort of a reminder to ourselves, from ourselves. I mean, really, how great a gift is that?”

“The main acoustic is a $100 Fender – the strings were super-old and dusty. We hate new strings!” Meet Great Grandpa, the unpredictable indie rockers making epic anthems with cheap acoustics – and recording guitars like a Queens of the Stone Age drummer

“You can almost hear the music in your head when looking at these photos”: How legendary photographer Jim Marshall captured the essence of the Grateful Dead and documented the rise of the ultimate jam band

![John Mayer and Bob Weir [left] of Dead & Company photographed against a grey background. Mayer wears a blue overshirt and has his signature Silver Sky on his shoulder. Weir wears grey and a bolo tie.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/C6niSAybzVCHoYcpJ8ZZgE.jpg)