Inside the long-awaited return of Mercyful Fate: metal guitar’s most unholy band

Guitarists Hank Shermann and Mike Wead join iconic frontman King Diamond to discuss the reanimation and macabre theater of a legendary heavy metal institution

Whether playing to packed US clubs or to tens of thousands of metalheads at Germany’s Wacken Open Air festival, there’s been nothing but love shown to Mercyful Fate since the Danish metal legends emerged from a 23-year live hiatus last summer.

Back in the Satanic Panic era of the 1980s, though, the quintet’s mix of occult themes and menacing riff-play was just as likely to make fans of horns-raising youth as it was to meet with the pearls-clutching consternation of parents’ groups and clergymen, who worried the band were nudging kids ever closer to the Dark Lord.

Formed in 1981 by the famously falsetto-voiced-and-corpse-painted King Diamond and guitarist Hank Shermann, Mercyful Fate re-envisioned '70s-period Purple-and-Priest with a demonic fervor.

Shermann and then co-guitarist Michael Denner ran hellfire scale-climbs through early bangers like Evil (from 1983’s Melissa), but also brought brutish prog intensity to pieces like Come to the Sabbath – a gothic epic off 1984’s Don’t Break the Oath full of quick-pivoting time changes, speed metal chunkiness and a finale where King, naturally, pledges eternal devotion to his “Sweet Satan."

Both their music and iconography were foundational for the first wave of black metal; in the '90s, good friends Metallica brought the blackest Mercy bits to the masses with Garage Inc.’s 12-minute Mercyful Fate medley.

Famously, the band were also listed as one of the “Filthy Fifteen” by the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC) in a 1985 US senate hearing, their Into the Coven cited as a step-by-step guide to bonding yourself with the devil – this among a catalog of similarly blasphemous rites like Desecration of Souls and Satan’s Fall. Ironically, being labeled obscene in the hearing alongside big-timers like Prince and Madonna raised the band’s profile in the long run.

Though Mercyful Fate first broke up in 1984 (they’d reunite for a run of albums in the 1990s), their legacy escaped unscathed by the moral panic of the PMRC. In another era, though, their musical blaspheming might have faced grave consequences. It’s a theme hinted at in The Jackal of Salzburg, a piece the band premiered live in Hanover, Germany, last June – marking the first new material from Mercyful Fate this century.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The song – which ebbs and flows between slow-mo metal gloom, clean-channel eeriness and Shermann’s malevolent vibrato – is inspired by real-life witch trials that took place in Salzburg, Austria, between 1675 and 1690, and the more than 130 people executed for supposedly living profane, perverted and possessed existences.

“It’s so grotesque, man,” the King reveals of the source material, adding that he only just recently learned of the church-and-state-driven massacre. “There was a young man, 20 years old, whose mother was burned alive as a witch in 1675. Two years later they started hunting [the son] based on confessions the mom had made under torture, where she gave up her son as being in league with the devil.”

They never found the Jackal, a man whom local lore insisted turned into a lycanthropic beast to terrorize the community at night; they did, however, murder a number of street children said to have been in his employ – many burned alive, maimed and tortured at Salzburg’s Moosham Castle in the name of “justice.”

“It’s pretty shocking when you think about spearing a child on this horrible thing that goes up your backend and comes out through your mouth, or on a wheel that would pull them apart,” King Diamond adds, “Completely insane!”

As legends are wont to do, Mercyful Fate’s The Jackal of Salzburg grew in scope over the summer as the band – comprising Shermann, King Diamond, guitarist Mike Wead, Armored Saint bassist Joey Vera and drummer Bjarne T. Holm – tweaked the arrangement on stage each night.

The song now sits above the nine-minute mark, and it’s due to be a part of the band’s next album – their first since 1999’s 9. While details are in flux, Shermann and King Diamond cautiously note with Guitar World that the next single will be more of a thunderous metal ripper; a ballad exists amidst the new tunes, too.

It’s a prolific time for the musicians, with King Diamond’s equally iconic and eponymous group – which has featured Wead on guitar alongside Swedish shredder Andy LaRocque since 2000 – also plotting their return with a two-part album titled The Institute. It’s expected to arrive ahead of the Mercyful Fate album.

For Wead, the return of Mercyful Fate is a chance to tap into the old black magic again, after abruptly halting the momentum at the dawn of the century to focus solely on King Diamond.

“I was still working together with King, even if it was as King Diamond instead of Mercyful Fate, but throughout the years I wanted to see Mercy get back together again,” Wead says. “We were really close; we also had lots of fun on the road. Of course, I was just waiting for the right time for it to happen.”

This is like my baby; it’s King’s baby. We started on the first of April 1981

Hank Shermann

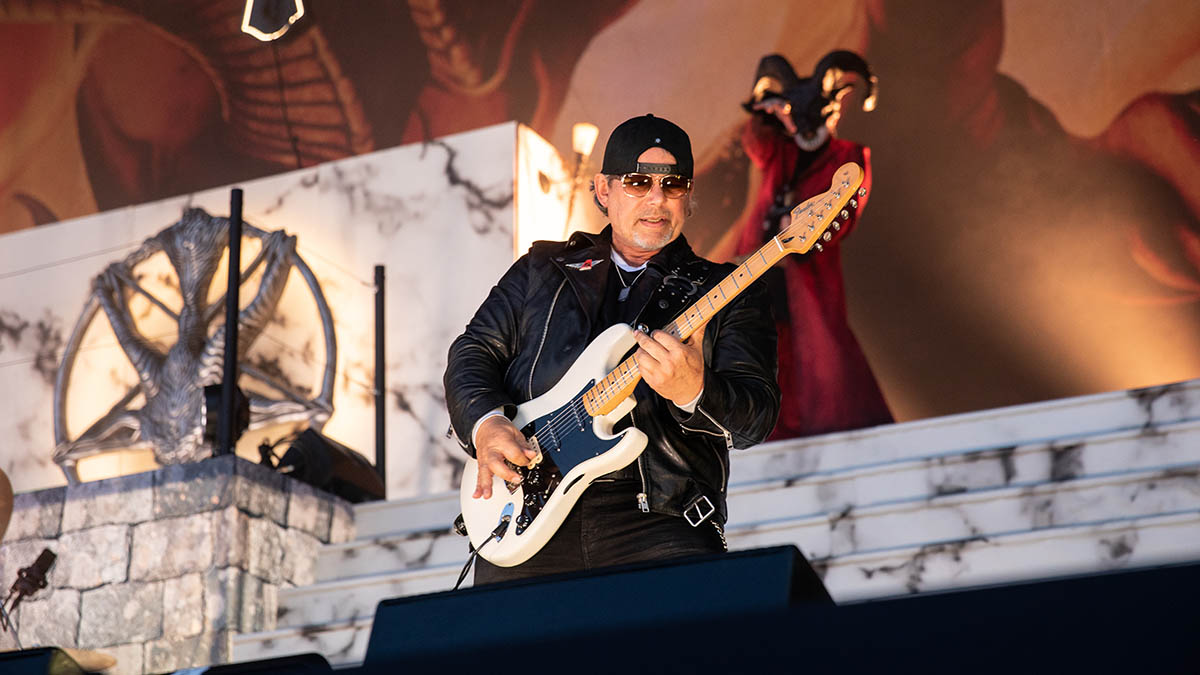

All this is to say, Mercyful Fate are finally back in fine, frightening form. While they delivered Grand Guignol morbidity to crowds in the early '80s – King’s mini-mic stand legitimately comprised a human femur and tibia – the group’s current stage aesthetic adds a beastly, eyes-aglow goat’s head mounted onto a pentagram behind Holm; an impressively ominous upside-down cross hangs high above the band.

And with its exquisitely coiled horns, King’s new mask has him looking extra devilish these days.

Across three separate Zoom calls with Shermann, Wead and King Diamond, the G.O.A.T.s of occult metal take stock of 40 years of hellish riffery, their Stratocasters-only sound, and why there’s no better time than the present for us to come to the sabbath.

How did you come to decide it was time to bring Mercyful Fate back, full-force?

Hank Shermann: “It’s something King and I have talked about over the years – we talk frequently [about] Mercyful Fate business, whether it’s merchandise, royalties or any other thing. I think the idea came to surface in 2012, but he had to do something with his band; later I launched the Denner/Shermann band.

“In 2018, we got hooked back on the idea, where King was ready and I was ready. It was officially announced [in] 2019, so it’s been a thing we have been discussing for, let’s say 10 years, off and on. And now the time just feels right for it.”

Timi had been there for a long time. He had a very unique style, playing with his fingers – a unique growl that one can hear in those early albums

King Diamond

In the leadup to these dates, King, you’d mentioned this wasn’t a reunion, but rather a continuation of Mercyful Fate. What’s the distinction there for you?

King Diamond: “Well, it’s practically the same lineup as the one we were playing with in 1999. We wished to have [founding bassist] Timi Hansen back, but he got sick [Hansen passed away in 2019 after a battle with cancer]. He got better for a while, but then he got sick again. It didn’t work in the end, but he was fortunately part of selecting Joey as a replacement. It was nice for Joey, as well, to have the opportunity to meet Timi. It was good vibes [despite] what happened.

What did it mean for the band to bond and reconnect with Timi before he passed?

King: “Timi had been there for a long time. He had a very unique style, playing with his fingers – a unique growl that one can hear in those early albums. So, that finger style became quite important to us, since we were playing these old songs.

“Timi already knew everything about Joey before I even mentioned [him as a replacement]. I went down and saw Joey play with Fates Warning, and it was amazing to hear the tone he has. Different… but so very close to what it sounded like. It’s been very easy for us to incorporate Joey into all the old stuff. He was all about honoring Timi. Joey is a permanent member in Fate now.

Mike Wead: “He treats it with lots of respect, you know. Even though I’m pretty sure he doesn’t play every note like Timi did, Timi never did that either. That was Timi’s thing – he was very in the moment as a bass player. In my opinion, that was one of his strengths. In any case, Joey is really doing exceptional with Mercy. I’m really happy to be stage-right with him; [it’s] our little home.”

What does the return of Mercyful Fate mean to you, creatively or personally?

Shermann: “This is like my baby; it’s King’s baby. We started Mercyful Fate on the first of April 1981. We were in another band just before called Brats [ed. a punky, late-'70s group from Copenhagen that at various points also featured Hansen on bass and Denner on guitar].

“We soon after split from that band and became fast-focused on different types of music – let’s say more Judas Priest, Uriah Heep and Sabbath-inspired stuff. We very quickly created our own songs, and it’s interesting that [despite] that little time-frame, 1981 to 1984, those songs still have an impact today.”

Mike, can you think back to the first time you ever heard about Mercyful Fate?

Wead: “I was in my mid teens when I heard the first EP [1982’s Mercyful Fate]. I was born and raised in the very north of Sweden, and this was also the early '80s, so you didn’t have anything like all the streaming platforms you have today.

“In the town next to mine, like half-an-hour away, they had a record store with [one clerk] who was into hard rock and metal. They had an import section, and there I found the Mercyful Fate mini-album. I thought the cover was so weird and evil-looking. I turned it around and saw the photo of King – he was so extreme for the time.

“I pretty much bought it without listening to it. I got home and I was floored. It sounded like a totally crazy, evil version of Judas Priest. When Melissa came out, I was trying to learn all the songs; same thing with Don’t Break the Oath. [They’re] still one of my favorite metal bands, even if I’m performing the songs.”

When you were learning those songs as a teen, were you picking up Hank’s parts or Michael Denner’s parts?

Wead: “At that time, I didn’t know which was which. I was just trying to pick up on everything. I had not been playing guitar for that long, so I thought it was very complicated to play those parts. But I learned a lot. It was really like nothing I’d heard – maybe a bit like Judas Priest, but more progressive. Because of that, it probably changed my approach to guitar playing, and my own composing style. It influenced me a lot.”

Hank and King, what do you remember about making those early records?

Shermann: “For the mini-album, we had a Volkswagen van. [We loaded] our Marshall cabs and 100-watt Marshalls – a 1959 Super Lead was what I had at the time – and then we drove off to this studio in Holland [Roosendaal’s Stone Studio]. The interesting thing with this is we performed it all live. Four songs in two days.”

King: “We could not do the things we had planned for: overdubs, backing vocals, choirs and harmony guitars. It was like, ‘No, there’s no time for this stuff!’ We needed an intro solo for A Corpse Without Soul. Hank had maybe done two attempts, and then the engineer said, ‘The one you’re putting down now is the one you’re putting on the album, alright?’”

Shermann: “When you’re in the studio and you only have two days, you’re under pressure. But that gives you a type of solo that might be more energetic, a little crazier, or more frenetic than if you’d [spent] four months at home trying to track that one solo. That’s what I liked about the old days.”

King: “We had six days [of tracking] to do Melissa; that was a lot for us! It might sound as if that’s not much, and it isn’t unless you’re really prepared. We had been playing all those songs to death, though, by the time we went into the studio [Copenhagen’s Easy Sound Recording].”

Shermann: “[While making Don’t Break the Oath] I went home one night and kind of copied a piece of Johann Sebastian Bach’s, from the Brandenburg Concertos, and I transcribed it. I taught Timi and Michael how to play it, and we added that to the ending of Nightmare. Overambitious, playing-wise, but I wanted to experiment. Maybe I had a little inspiration from Yngwie Malmsteen or Uli Jon Roth.”

Hank, you posted on Instagram about having to “brush up on songs you haven’t played in 20 years.” With the current setlist concentrating on the songs from the first EP, Melissa and Don’t Break the Oath, what was the hardest song to relearn, and likewise what came back to you like second nature?

Shermann: “I did a band with Michael Denner in 2015, and since we only had four songs [when we started], we had to look into the Mercyful Fate catalog. [Melissa’s] Evil is very easy; for some reason I’ve always jammed that in other environments, or with other bands.

“The most obscure is like Satan’s Fall [also off Melissa]. Me and Michael always did harmonies on the rhythm parts, but it’s a little blurry on the original recordings [who did what] – [there are] a few headscratchers on those parts.

It’s really tough to try and copy the recorded solos. If you try to be so on top of the original, you lose out on some musicality

Hank Shermann

“The rhythm sections and structures of the songs I’ve got figured out; the most difficult is to try and copy your lead sections. I was really punk and aggressive, and winging it in the studio – of course, I composed solos, too, but quite a few were winged in the studio.

“It’s really tough to try and copy the recorded solos; I try to keep the highlights. I learned that if you try to be so on top of the original, you lose out on some musicality. It’s better to loosen up and just make sure it has a swing with the music and the drums.”

A post shared by Hank Shermann (@hankshermann)

A photo posted by on

Wead: “For me, it’s been more about getting into the groove of the band. There’s so much rock ’n’ roll in Mercyful Fate; King Diamond is more of a strict thing, when it comes to the music. That’s the difference, for me at least, between Mercy and King Diamond: Mercyful Fate is slightly more old-school when it comes to grooves and riffs, whereas King Diamond wanted to go more theatrical and modern – a natural progression from Fate.”

King, you’ve written some classic Fate songs over the years, like Don’t Break the Oath’s Come to the Sabbath, or The Oath. Footage from the recent festival performances have shown you playing a mean air guitar on your crossbones microphone stand, but do you start writing your songs on guitar?

King: “Yeah, mostly guitar. For King Diamond I also write on keyboard, but Mercyful Fate is almost exclusively guitar. And whenever Hank writes stuff, I try to learn it [on guitar] so I know what’s going on. It’s a big help to be able to do that. Some of the [vocal] harmonies I’ll work out on guitar, and then I’ll sing it.

“But I don’t know music; you can’t give me a sheet of music and expect me to play off it. No way in hell! If the band are like, ‘This is in F minor,’ it’s like, ‘I’m sure it is!’ I have no intention to debate that; I have no clue. I can show you how I play it, though.”

Have you laid down any guitar on a Mercyful Fate record?

King: “Only tiny little pieces. Like, if there was a weird precision to the fingering, [the guitarists would be] like, ‘Why don’t you just do it yourself?’ It’s rare; only if necessary.”

Hank and Mike, what guitars are you taking out on tour?

Wead: “It’s a matter of what I think is right for the moment. I’ve been playing a lot of different guitars over the years – more modern Super Strats, like ESP Horizons – but these days I’m with Charvel, Jackson and, to some extent, Fender. On this tour I’ll bring three Strats with me: two Charvel So-Cals and one American Standard Fender.

“I do tend to favor the American Standard. I had it re-fretted with extra-jumbo frets, and I changed the pickup configuration – at the moment I only have one humbucker on it, because Hank is covering most of the single-coil parts in Mercy.”

Shermann: “Back in the day, I used a Strat with a [DiMarzio] Super Distortion. I have kept that since the '80s. I always use maple necks; that [adds] a little extra sharpness to it. Michael Denner always used the Flying V; maybe it was the combination of the Strats with that. Now I’m using a Hendrix Strat – reverse headstock with a Super Distortion in it.”

Hank, there was another Instagram post of yours where you’re playing the intro riff from Melissa at home, and you highlighted in the caption that the neck you’d played on the original recording was in the background. Curiously no body, though. Did anything notably dramatic happen to that guitar?

Shermann: “Yeah, there was a lot of drama to that guitar. First of all, I’d just made a big change from playing a Flying V to a Stratocaster, I guess because of Uli Roth. I just felt [at the time] that I had to have a Stratocaster. So, I went to this shop in Copenhagen and bought this deluxe Strat, a Japanese copy made by Morris – a very fine company! It had brass nuts, a brass saddle.

“I used that guitar for Melissa and the entire Don’t Break the Oath album. I installed the Super Distortion pickup angled the same as the single coil that was sitting in it before, kind of like what Eddie Van Halen did.

A post shared by Hank Shermann (@hankshermann)

A photo posted by on

“I had it on a US tour in 1995, but before we went over, I had a new neck installed. It turns out someone stole the guitar in New Jersey while we were loading in. So, away the body went! [Laughs] But I still had the original neck at home.

“Another time, [while I was] on vacation in the US, there was a flood in my basement in Copenhagen; the neck was laying there on the floor.

“It was underwater for at least a few days, and I couldn’t do anything about it because I was in the States. That guitar had a rough time! But it means a lot to me to have the neck, as I played it on the two famous albums. To my luck, I found the exact guitar for sale in a newspaper in 2019, and I went out to buy it immediately. It’s totally identical to what I had back then; it’s very precious to me.”

Rig-wise, what do you have going on at the moment?

Wead: “I use the Quad Cortex from Neural DSP. I have two of those with some custom profiles and presets that I made. That’s pretty much it. We don’t use any cabs onstage; we go straight to PA. I use a mix of wedges for the monitors on the stage, and in-ears. I take the clarity and the detail from the in-ears, and I take the power from the wedges.”

Shermann: “I’ve got two Kempers. Right now, I use a 1977 Marshall 2203 amp model that was profiled by someone clever; I use that as a main rhythm setting. I also use it for leads, [but while] boosting it a bit with reverb and delay. And then I have another setting where I use a lot of phase for Satan’s Fall.

“Back in the day, I had a Boss BF-2 flanger for the crazy intro to Satan’s Fall. For me, it’s all about making the tone totally authentic to 1983 or ’84.”

What can you say about The Jackal of Salzburg, the first brand-new material to surface from Mercyful Fate since the Nineties?

Wead: “It’s one of the more epic songs out of the new ones I’ve heard. It’s kind of bombastic, with a slight touch of doom metal, which is a bit different for Mercy. But then again, Mercy was never a band that stood still, either.”

What would you think the timeline for this next album is?

Shermann: “That’s a really good question, because I really don’t know, other than that I have at least eight or nine songs ready to be worked on. We already have three songs worked out, out of those, and the drums for The Jackal of Salzburg are recorded. I would also say it probably depends on what the reaction is from this US tour.

“Maybe we might rethink the order of the releases. The plan is that King Diamond will focus on their The Institute album, but at the same time [we’ll] work on the Mercyful Fate album. The Institute is designed to come out first. Hopefully they can both happen in 2023.”

Mike, do you approach guitar technique any differently between the projects?

Wead: “Well, we’re [mostly] doing stuff from the first albums, and, of course, Michael Denner was the guitar player on those albums. Therefore, like Joey’s done with Timi’s bass playing, I’m trying to respect Michael’s guitar playing. Even if we’re not the exact same style, I’m trying to stay in the same region.

“On King Diamond’s older songs with different guitarists, I’m trying to respect their stuff, too. Michael was much more '70s, early '80s influenced. He was more like a Michael Schenker – more rock ’n’ roll – while in King Diamond. If you listen to Pete Blakk, for example – who was on [1989’s] Conspiracy, and [1990’s] The Eye – he had a [then] more modern approach to guitar playing, like '80s shredder stuff. Two completely different guitar styles. So, in that way, I had to go to Mercy with a bluesy style.

“When I’m with King Diamond, I have to shred on the older songs. It’s a bit different in the technique because of that, switching between the '70s style and [being a] shred machine.”

We’ve just passed the 40th anniversary of the release of Mercyful Fate’s first EP; you’re now touring and writing music together for the first time since the late '90s. What keeps you all attached to the music and the musicians of Mercy after all these years?

Shermann: “For the music part of it, over the time-span of 40 years I haven’t really developed myself into too many other categories. Like, ‘Hey, can you play flamenco?’ I’m not sure. ‘Could you play a Beatles song?’ Again … I’m not sure! I’ve stayed fairly narrow, just playing my stuff in my own style.

“I haven’t bought new music for 25 years or so, so I’m basically listening to nothing. I enjoy my time going back to listen to [Judas Priest’s] Sin After Sin – oh man, it’s brilliant – but what really keeps me going is the composing phase. I’m always composing! I just can’t help it. That is for sure what keeps me going: chasing fantastic songs.”

Wead: “Looking from an outside perspective on the older albums, I still love them. They’re excellent; the reunion albums are really good, too. So I still like the music [the way] I did when I was a teenager. And the guys are like family to me – King and Hank and BT [Holm], and also the guys in King Diamond.”

King: “This is amazing, because I’ve been asked many times, ‘Are you going to do Mercyful Fate again?’ I’ve never said never – the day the stars align properly, absolutely. But it has to be done right. It cannot be [to just] go with a [stage] backdrop, collect some money and piss on the name of Mercyful Fate. No way! Hank has the same opinion. That goes for King Diamond in the future, too.

“We have names that demand respect from ourselves, and we will do that to the utmost. The [Mercyful Fate stage show] now is the way it should’ve been seen in the early days. It’s not the emperor’s new clothes. Now you can see the clothes.”

Gregory Adams is a Vancouver-based arts reporter. From metal legends to emerging pop icons to the best of the basement circuit, he’s interviewed musicians across countless genres for nearly two decades, most recently with Guitar World, Bass Player, Revolver, and more – as well as through his independent newsletter, Gut Feeling. This all still blows his mind. He’s a guitar player, generally bouncing hardcore riffs off his ’52 Tele reissue and a dinged-up SG.

“I always felt like that record could have been better if we had worked on it some more”: Looking for a blockbuster comeback album, Aerosmith turned to Van Halen producer Ted Templeman. For Joe Perry, it served as a learning experience

“It's like saying, ‘Give a man a Les Paul, and he becomes Eric Clapton. It's not true’”: David Gilmour and Roger Waters hit back at criticism of the band's over-reliance on gear and synths when crafting The Dark Side of The Moon in newly unearthed clip