Mdou Moctar: “I really like the Stratocaster sound. Whatever tone I need, I can have it in that guitar”

Strat in hand, the Nigerien phenom is taking Tuareg guitar music global and putting an electric twist on traditional arrangements

Every now and again some wiseacre pops their head out to herald the death of the electric guitar. But they’re not really listening to what’s going on, and they’re definitely not taking into account the revolutionary power of fresh perspectives on the instrument.

Take Mdou Moctar; scarcely has a Fender Stratocaster sounded more alive than in his hands. Based out of Agadez, Niger, Moctar takes the traditions of Tuareg guitar music and the traditions of the Strat, and braids them together into one thread for a propulsive, psychedelic sound that is at once delivered with the cathartic oomph of celebration and the urgent cadence of protest.

Surrendering to the insistent, hypnotic grooves of Moctar’s sixth album, Afrique Victime – released through Matador – is a potent psychedelic experience.

Delivered in Tamasheq, Moctar’s songs are of love and peace, of the ruinous impact of French colonialism on his home country.

Moctar’s restless songwriting has evolved over the years. His debut album, Anar – recorded in Sokoto, Nigeria in 2008 – paired acoustic Tuareg guitar with vocals heavily processed in Auto-Tune more commonly found in Nigeria’s Hausa and Nija scenes.

This radical new sound soon spread across the continent’s central belt via cell-phone music trading networks – an African facsimile of the tape-trading movement – before coming to the attention of a Sahel Sounds’ Christopher Kirkley, who featured Moctar on his Music from Saharan Cellphones: Volume 1 compilation.

Moctar always wanted to be a pro musician, to be a star, and now he had an audience. As it turned out, people did want to listen to Tuareg arrangements on acoustic guitar and Auto-Tuned vocals. People wanted something new. So did Moctar.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Yeah, my first album, Anar, I did it with the acoustic, and I had never listened to Auto-Tune, but the sound was so great,” he says. “I had never listened to Auto-Tuned music before but I said, ‘I have to do that! I have to have it.’

“Because I am a person who likes to listen for a new thing. I like to make some something very new, and so I wanted to do this music in Auto-Tune, I was going to see how the Tuareg music would sound in Auto-Tune.”

In 2013, for the recording of his second album, Afelan, Moctar returned the village of his birth, Tchintabaraden. Opening with the acoustic traditionalism of A Fleur Tamgak and a skronky, vital and alive cover of Tinariwen’s Tuareg anthem Chet Boghassa, Afelan takes on a life of its own.

In the five years since Anar, Moctar had foregrounded the electric guitar, and the trebly bite of the Fender Stratocaster proved to be the perfect medium for his songwriting. “I really like the Stratocaster sound,” he says. “Whatever sound I need, I can have it in that guitar.” But at the beginning, finding a guitar was easier said than done.

My family didn’t want me to be an artist. They thought that when I become an artist I am going to start to drink alcohol or take drugs!

The history of guitar-driven music has been driven by the pursuit of a new sound, a new kind of kick, but it has also been shaped by trial, error, innovation, and the unconquerable will to make this sound happen, no matter the adversity. Many of the greats have not had it easy. Many had to box clever to get their sound together.

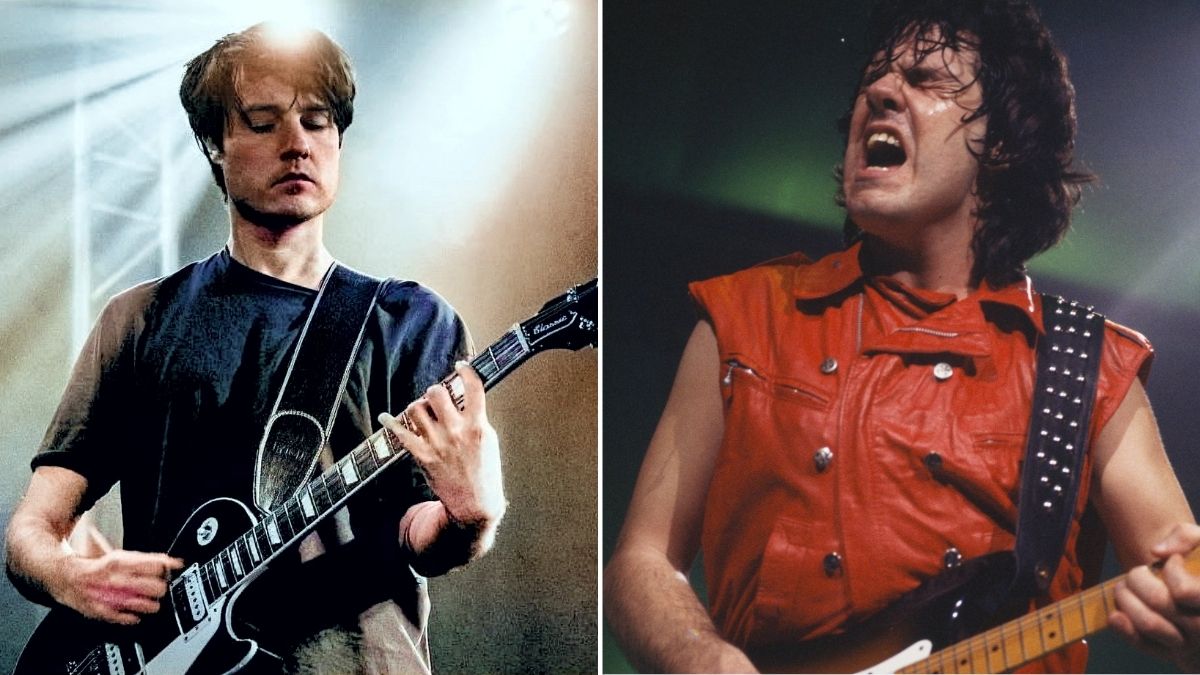

There were those who have had to overcome physical barriers, most notably Django Rienhardt, who lost the use of his fretting hand’s ring finger and pinky in a fire, and Tony Iommi, who lost the tips of his fretting hand’s middle and ring fingers in a machining accident.

Then there are players who have found logistical barriers between themselves and the instrument, such as those who could not afford a guitar, and have then had to take matters into their own hands and find a DIY solution. Brian May springs to mind. What connects all of these players is imagination and determination.

Having seen ishumar “desert blues” pioneer Abdallah Oumbadougou of Desert Rebel perform, Moctar had to get a guitar somehow.

“It was it was like, ‘Wow!’ I had to have a guitar,” he says. “I saw him at my first concert. He played outside for everyone.” But the guitar was something that he was forbidden to own – his family are devout Muslims and didn’t look too kindly on a musician’s lifestyle.

“They didn’t want me to be an artist,” he laughs. “They thought that when I become an artist I am going to start to drink alcohol or take drugs. When I started to be a musician, my mum was very scared. She was scared I was going to leave my school. And then that happened; in secondary school, I left to be an artist.”

His problem was two-fold, however, because, there was nowhere to buy a guitar in his village. The only way to get one was to build one from scratch.

“I did not know what I was going to do,” he says. “So, I just built my guitar by myself. I took some wood and I made a guitar. But it was just one part – it was not a real guitar. Then I took the cable from the brakes for a bicycle. I, like, took the small, small cable and made it into a string. My first guitar had four strings. That helped me a lot in the beginning.”

With four strings teased out of a brake cable and positioned on the wood, the guitar took shape. Yes, it was primitive. And yes, without question, his family thought it was ridiculous. But that gave him the cover he needed to tweak his design and to practice without arousing suspicion.

“For the tuning I used a key like we have for opening sardine tins,” he explains. “I had four like that for the tuning. It sounded so awesome. I liked it. I played that and my family doesn’t think that it is serious. They think that it is junk! It’s nothing. It’s cheap. ‘He’s young! It’s nothing…’”

If Moctar felt restricted at home, or by the lack of gear options in rural Niger, the desert nonetheless offered a sense of freedom in other ways. All musicians are the product of our environments to some degree. Some draw from the energy of the city, from the hybrid vigor of a scene. Moctar has the desert.

The sky and the stars, that inspires you when you want to write something or when you need to play. It is like you are free

He has described Tuareg music as the sound of the desert. In conversation with EarthQuaker Devices in 2019, he said that “the drums are the rhythms of the camels.” He had wide open spaces and a night sky without end.

“The sky and the stars, that inspires you when you want to write something or when you need to play,” he says. “It is like you are free. It’s a feeling of being free to do whatever you need to do. The wind, too, is great, to have that through the song at night is something very spiritual. I love the desert because it is so quiet. It’s empty.

“There is no sound for miles. Not one person, not one car. Nothing. Everything is quiet and you can do whatever – you can just live for yourself. There is nothing to interrupt you. Then, at night, you are going to have that sky, so many stars, and it’s so dark, and then the wind… It’s great. Yeah, the feeling is fucking amazing.”

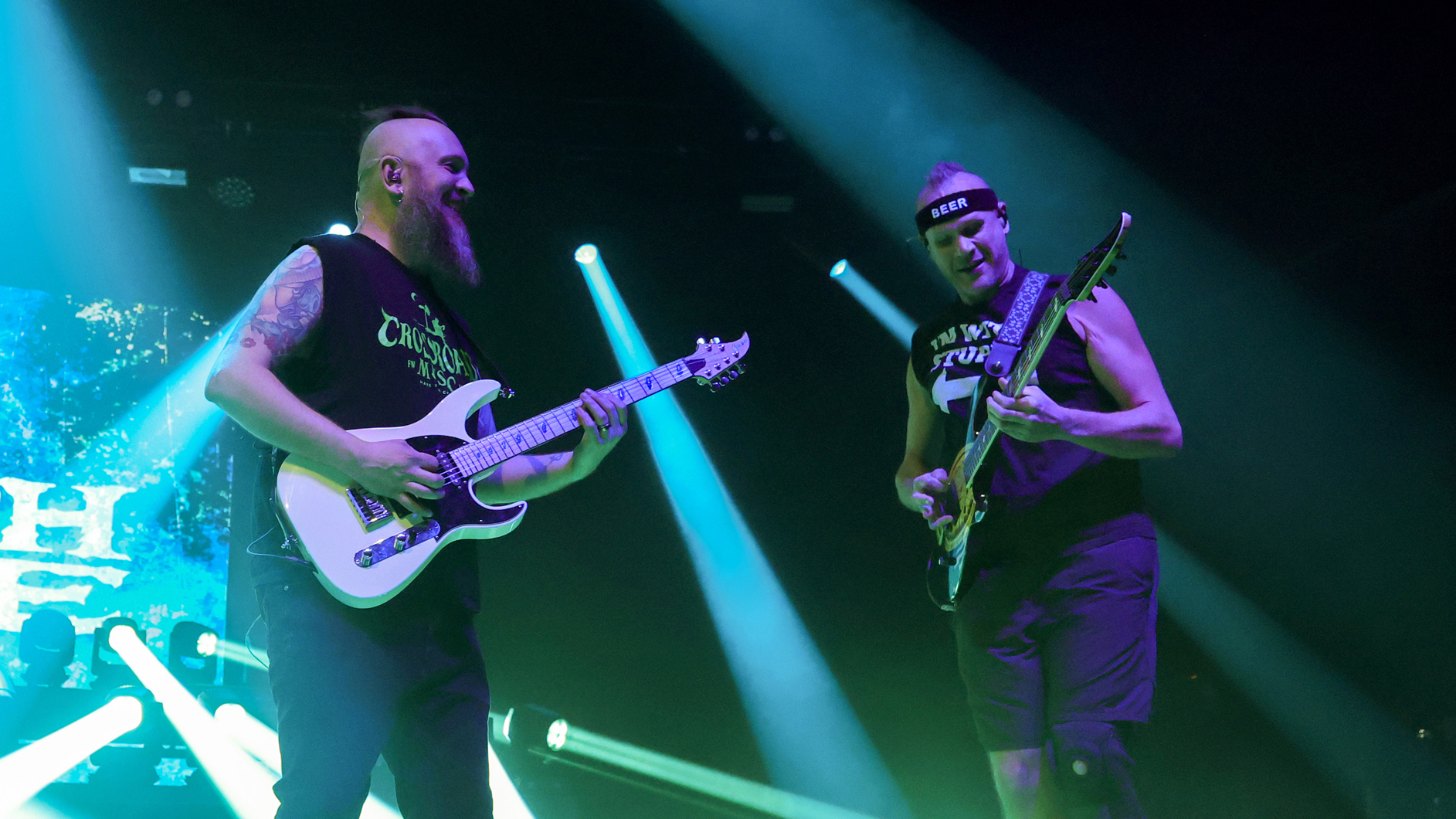

Moctar’s band comprises Souleymane Ibrahim on drums, Mikey Coltun on bass and Ahmoudou Madassane on rhythm guitar. Madassane has been been with the band since 2008, having grown up close by and receiving his first acoustic guitar from Moctar.

Coltun, however, does not live close by. He’s from Brooklyn and has a 48-hour commute by air and bus to attend practice and recording sessions in Agadez. He’s also the band’s tour manager, producer and engineer. He even drove the tour van.

“Michael supported me for a long while,” says Moctar. “When I was in New York, and he was at the concert, he said, ‘Christopher never answered me but I am really enjoying what you are doing. I really love what you are doing, when you need a bass player you just have to get in touch.’ For time he was the driver and the manager, and now he is the bass player in the band.”

Afrique Victime was recorded in various locations while on tour, snatching a couple of days’ studio time and tracking a couple of songs before hitting the road again. “Doing the album during the tour stressed me a lot because it is hard,” says Moctar.

“I am on tour, it’s Ramadan, I miss my family, and then I have to make something really great! That was very difficult for the album, but I love it. I love what I am doing.”

Moctar and band would go from the show where the energy was already there from the crowd, then to a studio, where the red light goes on and you have to create your own energy.

The challenge then is replicating the vitality of the show on tape, and finding a performance out of nothing. Having workshopped his sound playing Tuareg weddings, he feels far more at home on a stage.

“The studio is not like a concert,” says Moctar. “It is like you are at school; you have to apologize. You have to be more serious than an a concert. Everything is like ‘tick-tock, tick-tock, tick-tock…’

I prefer the concert to the studio. In a concert, everyone is singing and everyone is dancing. It is not just you. It’s not just your energy, it is the energy of everyone

“I prefer the concert to the studio. The studio obstructs me a lot. In a concert, everyone is singing and everyone is dancing. It is not just you. It’s not just your energy, it is the energy of everyone.

“The studio is a different energy. Everybody listens to you, and only you. You have to do something special, just you! In a concert, the people push you to do something you could not do before.”

Moctar’s style is such that he doesn’t need too many pedals. The rhythm, his phrasing, and a self-taught fingerstyle technique that incorporates the influence of Eddie Van Halen, all conspire to make his sound less ordinary.

Circa-2019, he would use a pair of Roland Jazz Chorus 120 combos, with a pedalboard populated by a Boss OD-3, the Hoof fuzz and Bellows overdrive from EarthQuaker Devices, plus an Electro-Harmonix Bad Stone and a Boss DD-6 delay that would be run in stereo.

Pedals remain a new frontier, with phaser, chorus and delay all favorites. Moctar will return from tour with different items of gear, but at home digital modeling amps such as the Fender Mustang and Roland Cube offer all-in-one solutions for processed guitar tones.

But while the songwriting will surely evolve, Moctar isn’t going to be changing up his tone or his technique any time soon. That’s what the people have come to hear.

“I like what I am doing, the sound I have at the moment,” he says. “I don’t want to change my sound too much. I want to keep the sound as a very traditional sound. Because if you listen to my guitar, how I touch the guitar, it is so different. It is very traditional; it’s not guitar! It is… Something!”

- Mdou Moctar’s Afrique Victime is out on 28 May via Matador Records.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to publications including Guitar World, MusicRadar and Total Guitar. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.

“I heard the Money solo and thought, ‘This is amazing!’ So I sent David a telegram saying, ‘Remember me? I'm in a band now called Roxy Music’”: Phil Manzanera on his friendship with David Gilmour, and the key to the Pink Floyd man's unmistakable tone

“It’s really quite genius, but also hard to learn – it sounds insane, but sometimes the easiest songs still get me nervous”: Kiki Wong reveals the Smashing Pumpkins song she had the most trouble with