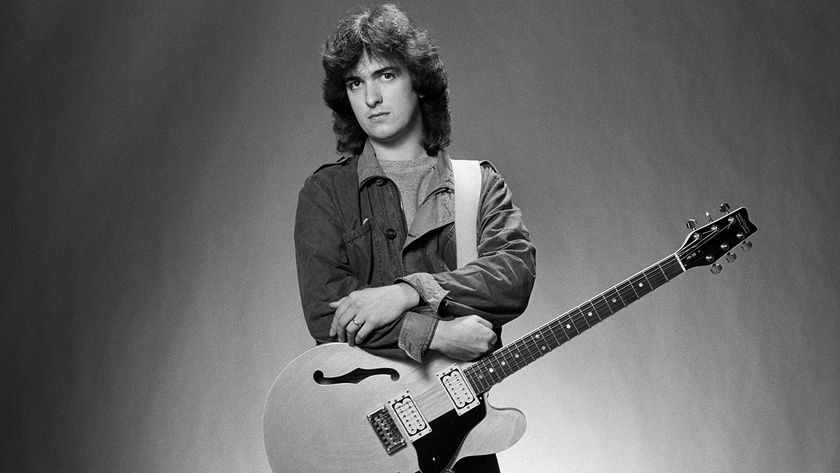

Mark Seymour: On The Dawn Of Greatness

Most of us pass the time on road trips by reading or playing games. Mark Seymour, on the other hand, writes albums.

In the words of Mark Seymour himself, “The songs on Slow Dawn are, in many ways, a search for home through a landscape of decay, love and memory.

Much of my thinking takes place behind the wheel. All of the songs are triggered by travel, looking out at the land.”

On his fourth album leading Mark Seymour & The Undertow, the 63-year-old Victorian luminary – an icon of Australian rock due both to his solo work and as the frontman of Hunters & Collectors – looks further outward than ever before, finding inspiration on‑the‑fly and in unexpected places, rather than in dedicated notebooks or longwinded songwriting sessions.

We were lucky enough to get a glimpse of how the man works his magic – here’s what we learned...

What is it about being on the road that you find so creatively liberating?

I tend to do a lot of thinking when I’m on the road. Driving is almost like downtime – you’re not necessarily talking to people, or being engaged with anything mentally stimulating – it’s a real neutral space. And over the last few years, I’ve become more and more aware that the potential for creative thought is enormous when you’re in that kind of content. And I always tend to look for ideas as I’m moving around – I don’t sit down and plan my songwriting, y’know? I take a lot of notes and I make a lot of really short little recordings into my phone. There’s a lot of scratchy activity, which I’ve becoming a lot better at judging the benefit of, lately.

I remember when I first started as a solo artist, I felt compelled to get into that whole DIY multitrack world – I bought myself a version of Pro Tools and I did a lot of things that a lot of artists do, y’know, thinking they’ve got to create their own sort of artistic mastery in their bedroom. But I moved on from that as time went by – when I realised I wasn’t actually writing great songs. The quality of the song matters more in the end, and I think that you’ve really got to be connected with something much deeper, psychologically, to come up with good work. And for me, that tends to happen more when I’m moving around, so I had to work our a more portable way of recording.

If I went into the Voice Memos app on your phone, would I just see thousands of rough little demos in various forms?

Pretty much, yeah. We’ve got a little methodology going with the band – I’ll send a bunch of files over to them and go, “Here’s what I’m working on – let’s book a rehearsal in somewhere.” Then they’ll go, “Okay, what night are you free?” And I’ll say, “Ah, whenever.” And then I’d just rock up to some rehearsal room I’ve never been in before and start playing the songs. That whole process of just being really random and energetic and simple – it’s perfect for us.

All of these guys have been in bands before and they’re all pros, so we’re able to really just throw shit at the wall and see what sticks. There’s only four of us, and the whole project has got a lot of spontaneity to it, which I really like. It just keeps things fresh. And you get good results from it!

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Because records are like chameleons – they’re constantly changing colours. So if you have one common thread throughout the process, it has to be the energy – you’ve got to have energy at the end of the process, because you hear that in the final product, and it’s got to be there from the start as well because otherwise it ends up being too forced.

A lot of these tracks have a very raw and personal flavour to them, but you could almost rework a bunch of them into pop songs if you wanted to. Is there an intentional level of duality that you strive to hit with your songwriting?

If I don’t feel emotionally connected to the track, it never sees the light of day. I’ll sort of nibble around an idea for a long time, and hopefully it’ll either connect with me or I’ll find some way into it emotionally – there’s a way of singing it I can get my head around, or there’s a line in there that somehow clicks with my psychological state. And when I find that connection, that’s when it ends up becoming a song. Because I know that when I go to play it for the other guys, I’m going to believe in it. I’ll be at the microphone going, “Here it is guys, the next masterpiece!” But if I don’t have that feeling, it won’t go very far – regardless of whether it’s a love song or a political song or whatever; if I haven’t got that feeling of passion and charging when I step up to the mic, I just won’t bother with it.

How did you find writing this album to be stimulating for yourself as a guitarist?

I’m really not a great guitar player [laughs]. I am pretty fussy with it – I have a set of chord clusters that I go to, and I’m really passionate about the different tones and how I can work with them. I use capos a lot, because I’m always looking for harmonic tone that I feel emotionally connected to. So there’s specific setups that I look for and return to a lot. And I’ve got a pretty reasonable vocabulary, chordally – but again, it’s still all just chords and melody; I’m not that good on a technical wavelength.

Fortunately I have Cameron McKenzie in the band, and he is an incredibly good guitar player. He’s just nuts. Absolutely nuts. But y’now, the guitars are a big part of the conversation in this band – we talk about them all the time and we discuss the different parts of the songs a lot. I’m a huge fan of the Fender Telecaster, I have to say. Although that’s actually an interesting point – I’ve come back to playing the electric guitar a lot more than I used to. I went to the acoustic when I went solo, and I still write on acoustic guitars, but the Telecaster is definitely a much bigger part of the picture now than it used to be.

What is it about the Tele itself that you can’t get enough of?

It’s well set-up; the pickups are quite specific, but they’re loud, and they’re single-coil pickups so they’ve got a very narrow band, which means you can smash the shit out of it and it doesn’t flinch. I’ve tried playing Gibsons, and I just find them a bit too loud for me. They’re just too big of a sound – because I’m playing raw chords aggressively, while I’m singing, so the guitar has still got to sound tuned on the harmonic and not take over what I’m doing on vocals. It’s got to compliment what the melody is doing. And I find that the Gibson tends to be too ballsy and fat for what I’m usually going to put it to. It tends to just take over and dominate.

The thing with the Tele is that it’s really transparent; it can sit inside the band and have this real gritty mid-range toughness to it, but it doesn’t interfere with what everybody else is doing around me. With the Undertow, it’s like there’s a conversation happening between the bass player and the guitarist, which is very eloquent; they riff off each other, and I’m sort of sitting in the middle between them, holding the chords down. And I think the simplicity of that arrangement is actually what contributes a lot to how the band works out its sound.

Ellie Robinson is an Australian writer, editor and dog enthusiast with a keen ear for pop-rock and a keen tongue for actual Pop Rocks. Her bylines include music rag staples like NME, BLUNT, Mixdown and, of course, Australian Guitar (where she also serves as Editor-at-Large), but also less expected fare like TV Soap and Snowboarding Australia. Her go-to guitar is a Fender Player Tele, which, controversially, she only picked up after she'd joined the team at Australian Guitar. Before then, Ellie was a keyboardist – thankfully, the AG crew helped her see the light…

“We had 15 minutes left, and it was time to go… I just started playing that riff. Then Lenny goes, ‘Whoa, what’s that?’” Lenny Kravitz guitarist Craig Ross reveals the serendipitous roots of a Kravitz classic

“The concept of the guitar duel at the end was just appalling”: Crossroads is an essential piece of '80s guitar lore, but not every guitar legend was a fan of the film