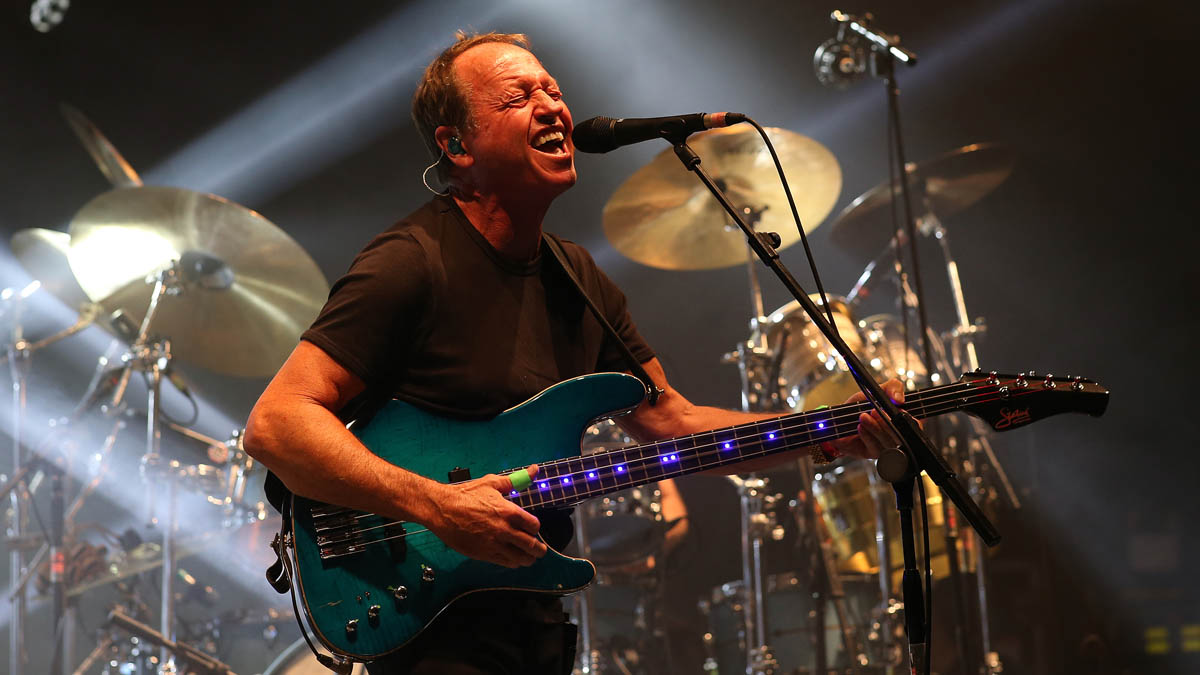

Mark King: “Level 42 were so successful in the '80s. No-one was more surprised than me at how big the band became”

As Level 42 celebrate four decades in business, we sit down with King and take a look back - with the benefit of 2020 vision

Mark King has been on the cover of this magazine quite a few times in its existence, and as befits a bass player of his profile, when interviewing him we’d normally take him out to dinner, do a photoshoot in a posh hotel, quaff a series of fine cocktails and generally behave in a thoroughly celebratory manner.

Today, though – or rather on April 22, 2020, some weeks at least before you read this – he and I are sitting at our computers in our respective home offices. That’s the current pandemic for you. Still, though, there’s an air of celebration throughout our chat: King’s band, Level 42, have reached their 40th anniversary this year. What better time to look back at a career at the cutting-edge of bass guitar?

First off, it emerges that Level 42 have been hit by the same wave of gig cancelations as every other performing band. This virus is no respecter of anniversaries, apparently.

“We’ve had so many shows drop off the calendar because of lockdown, but obviously we’re not alone there,” explains King.

“It’s happened for so many bands, but we had a particularly busy year set up. We had a big Australasian tour, with 10 shows in Japan, three shows in Australia, a show in New Zealand and a show in Singapore: They went straight away. We were doing an orchestrated thing with the BBC Concert Hall on 16 March, too, but that didn’t happen for obvious reasons.”

It seems that 2020 is going to be the year that never was, but that aside I’m very happy with things

King is also fairly confident that he and his family also got a dose of COVID-19 themselves, although it’s difficult to be sure about that given the current test-free situation in this country.

“It was the strangest feeling,” he tells us. “My wife, Ria, my daughter, Marlee, and I all had a cough, and painful arms. You know when bullies at school used to give you a dead arm? It felt like that. And the other weird thing is that it came in waves, so you’d be all right for a bit – and then it felt like someone yanking your spine out. Thank goodness we came out the other side of it.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Like most of us, he’s counting his blessings, not least because he was able to play online gigs for events such as Camp Bestival. Check YouTube and you’ll see him and Marlee delivering a bass and vocal duo performance, aided by backing tracks, from his home studio on the Isle of Wight on April 12.

“It was great to do Camp Bestival,” says King. “Everybody has to be proactive at a time like this. It’s no good just sitting back and wondering what might happen, and fortunately I can perform in the studio. I’ve got three cameras set up here and they’re great quality, not that you could have seen anything before I cleared everything out a while back. There was so much gear in there that I couldn’t physically get inside.”

That’s 40 years of being in a band for you, we suppose. “I’ve still got a garage full of it,” he chuckles. “I upgraded the studio computer three months ago. I have a Mac Pro and an Apollo X16 interface, but even after the upgrade I still had the old Mac Pro sitting there.

“You think to yourself, ‘I’m upgrading just to see how this goes, I’d better keep the old systems standing by.’ I had 16 guitar cases standing in the corner and a palette of 5000 DVDs of the last tour we did. It was just chaos. In the end I filled up two skips with junk and added industrial shelving. It’s been a real game-changer.”

Talking of gear, King has switched to a new Status Graphite bass and a new go-to amp since we last spoke to him. The former is a headed instrument, based on a relatively little-known but acclaimed bass.

“It was inspired by Trace Elliot’s T-Bass from 1996,” he explains, reaching over to show the bass to the camera. “When the Gizmodrome project happened three years ago, I was in the studio with my usual Kingbass, working with Stewart Copeland, Adrian Belew and Vittorio Cosma and yes, I’m Mark King and I’m known for slap bass, but that wasn’t the gig. I found myself using a pick as much as fingers because the music needed that kind of hard attack.”

He continues: “There was a 1967 Jazz bass hanging around in the studio we were recording in, so I pulled that out – and straight away, that sound was much more suitable. I gave Rob Green at Status Graphite a call and asked him if he could do something more retro, like the T-Bass, which I’d used on one of [Sting guitarist] Dominic Miller’s solo albums.

The massive success that Level 42 enjoyed during the 80s never seemed inevitable to me. I knew it would change at some point, simply because it always does

“I loved the sound and it was so easy to record with, and it slaps great too, so I ended up using it with Level 42. And there’s a new version on the way – Rob was just finishing off the next evolution of this bass before we went into lockdown. He offered me the chance to make it headless, but there’s something about the gravity and the density of having a headstock. If you chop the end off, it’s going to affect the sound somehow.”

The new amp, a Markbass, was chosen to complement the warm tones of the new bass, King explains. “It’s a new model, the Little Mark Vintage, that Marco [De Virgiliis, Markbass owner] was excited about. It’s quite retro, with a lovely, warm sound which suits the T-Bass very well.

“I had a Markbass rig in the early 2000s, and a head that I’d carry around as a backup, which was very light and portable–I’ve always really liked them. This one is a new model which coincided with me leaving TC Electronic.

“The only change I’ve made to it is that because there are so many transients in the way I play, I asked them to knock up a 1000-watt head instead of the regular 500, for some extra headroom. Other than that, I’m still using Rotosound strings, of course – those guys have always been there for me – and Radial Design too. I always have loads of Radial bits knocking about.”

With 40 years’ worth of bass gear around, does King ever sell any of it on eBay when he no longer needs it?

“No – because most of the stuff has been given to me by sponsors, and as an endorsee I don’t think it’s right to sell it, just because I’ve moved on. For example, Rob Green comes up with three or four basses each year for me, so over the years I’ve had an awful lot of instruments. If I sold them, it would impact on Rob’s sales, so I use them for charitable donations.

“I’ve donated them as fundraisers for Nordhoff-Robbins and for Beaulieu Respite Care here on the island, where I’m a patron – that seems to be the best way to do it. You’ll recall that your magazine organized a Music Man bass for me from [Ernie Ball’s UK distributor] Strings & Things; it was very nice of them to send me one. I took it to a Children In Need event where it was auctioned and made $10,000, which was incredible.”

Switching to the subject of Level 42, King is in a rather different position in 2020 than he was as a 21-year-old back in 1980. For starters, he manages the band: “I’ve done that since I got the name back and got the band going again in 2002,” he explains. So how does the musical landscape appear to him these days, current crisis aside?

My ancestors were farmers who never left the village they grew up in. My aunt was born and died in the same house, too. I find all that a little depressing when there are so many amazing things to see in the world

“It seems that 2020 is going to be the year that never was, but that aside I’m very happy with things,” he says. “Level 42 were so successful in the 80s – and believe me, no-one was more surprised than me at how big the band became, with arena tours and bucketloads of album sales, which was wonderful. That all stopped in 1994 because I pulled the plug on it. The whole music landscape had changed.”

What changed, exactly? “The record companies and publishers that we were working with started losing faith in us because album sales had dipped,” he explains. “I suppose it’s the same in any kind of business–people always want to see business expand rather than reduce. I remember going to see [A&R executive] Clive Black at EMI around 1994; he played me Lucky by Lewis Taylor, which is a fantastic song that blew me away.

“I said, ‘What are you going to do with that?’ and he said, ‘I love it, but I haven’t got a clue. After this meeting I’ve got to go and talk to the suits, who are going to say, ‘Last year you made this much money, Clive. This is how much we expect you to make this year. How are you going to do that?’

“He didn’t think he could do it with a track like Lucky, which was disappointing, although it wasn’t entirely unexpected because I know what record companies are like.”

The early to mid-90s were a strange time for popular music, as readers with long memories will recall. In a short period of time – say 1991 to 1994 – 80s pop was made to look obsolete overnight thanks to grunge, alternative music and the beginnings of Oasis-style lad-rock.

Fortunately for King, he saw it coming, unlike many of his contemporaries.

“The massive success that Level 42 enjoyed during the '80s never seemed inevitable to me,” he muses. “I knew it would change at some point, simply because it always does. What goes up must come down. I’m really grateful that we were able to maintain it as long as we did, because we went through line-up changes and the loss of Alan Murphy [Level 42 guitarist who died in 1989] and so many other setbacks. They would have made a lot of bands throw their hands in the air and quit.

“All that being the case, 1994 seemed like a good time to try and do something else, so I released my solo album, One Man, in 1998. When I started touring with it, it was a much more scaled-back affair than the Level 42 experience had been, because I was playing to audiences of 600 to 1,000 people.

“The budget wasn’t there [for a large crew] because of the fees I was being paid by the promoters – but I absolutely adored that experience because it was a great leveller. It’s important as an artist to realize that your audience isn’t waiting for you, because somebody else will come along.”

Here in 2020, what advice does King have for readers of this magazine about making a living in the music industry?

“Well, how it will all unfold in the future, I don’t know, because the whole scene has changed,” he says. “But there are certain business skills that everybody needs. For example, when we tour I always work on a guaranteed fee from the promoter. I have to have that guarantee, because then I know what my budget is and I know what I can pay the guys in the band and the crew.

“All the things that have to be done – production, catering, lights, the whole thing – you’ve got to know that you can cover that: If you throw caution to the wind, you could easily go bust.”

A lot of musicians focus more on being creative than on the financial housekeeping of a business – accounts, book-keeping, managing tax and so on. Should more of us acquire these skills?

It was great to do Camp Bestival. Everybody has to be proactive at a time like this. It’s no good just sitting back and wondering what might happen

“It would seem to me to be a necessity,” he says. “Of course, you can get accountants and you can get managers, but to me those were things that I could do myself because I was always interested in them. When somebody offers you a contract, read through it. It may seem really wordy and verbose, but stick with it and make sure you understand it.

“Record companies and publishers always used to insist that you got a lawyer involved, so they couldn’t be held over a barrel if you later said that you didn’t understand what was signed. At the same time, legal costs can take a big chunk of your income – so if you can cover that stuff yourself, you’re off to a better start. I was happy to do that and get stuck in, but I know a few musicians who don’t want to know.”

What advice would he give his 21-year-old self if he could travel back 40 years?

“Actually, I don’t think I’d give him advice,” he reasons, “but I’d certainly tell him that he was going to have the best time. I’d say ‘Some amazing things lie ahead of you, so don’t take any of them for granted’. For me, the high points were playing with amazing musicians and travelling the world.

“I grew up on a prison estate on the Isle Of Wight and my ancestors were farmers who never left the village they grew up in. It was scary, in a way. My grandparents lived at opposite ends of the same street here, got married, built a house on the same street and died on that street.

“My aunt was born and died in the same house, too. I find all that a little depressing when there are so many amazing things to see in the world. Going to Europe for the first time, and seeing the different cultures, was wonderful. Meeting German and French and Scandinavian people was incredible. Don’t get me started on Brexit... So many people have had that opportunity taken away from them.”

Thanks for the interview, Mark, we tell him: there are plenty of home truths for us all to digest. He laughs; “Well, that’s the wonderful thing about getting to 61. You say what you want – and people can either take it or leave it!”

- See Level 42 for details on the band's 40th anniversary tour.

Joel McIver was the Editor of Bass Player magazine from 2018 to 2022, having spent six years before that editing Bass Guitar magazine. A journalist with 25 years' experience in the music field, he's also the author of 35 books, a couple of bestsellers among them. He regularly appears on podcasts, radio and TV.

“The main acoustic is a $100 Fender – the strings were super-old and dusty. We hate new strings!” Meet Great Grandpa, the unpredictable indie rockers making epic anthems with cheap acoustics – and recording guitars like a Queens of the Stone Age drummer

“You can almost hear the music in your head when looking at these photos”: How legendary photographer Jim Marshall captured the essence of the Grateful Dead and documented the rise of the ultimate jam band

![John Mayer and Bob Weir [left] of Dead & Company photographed against a grey background. Mayer wears a blue overshirt and has his signature Silver Sky on his shoulder. Weir wears grey and a bolo tie.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/C6niSAybzVCHoYcpJ8ZZgE.jpg)

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)