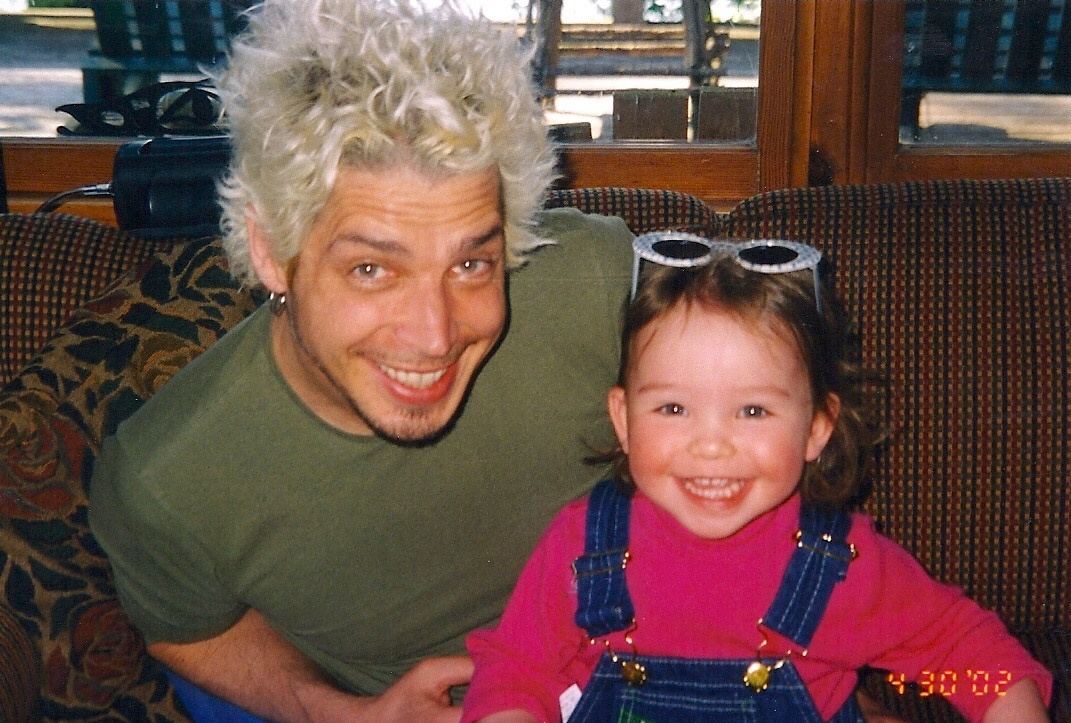

Lily Cornell Silver: "Mental health is such a ubiquitous issue in the music industry"

As part of a new GW series on mental health, the activist, musician and daughter of Chris Cornell discusses breaking down barriers with her Mind Wide Open interviews

As part of Mental Health Awareness month and beyond, Guitar World will be hosting a series of interviews and features with artists addressing and raising awareness around themes of mental health, particularly as they relate to musicians. Below, we present the first of these interviews.

Last July, with the world on lockdown, touring at a standstill, and increasing numbers of people experiencing mental health challenges, Lily Cornell Silver launched Mind Wide Open, an Instagram series in which she interviews musicians, actors, artists, and mental health professionals. The program is now in its second season, and featured conversations with the likes of Eddie Vedder, Duff McKagan, Fantastic Negrito, Taylor Momsen and Ann Wilson.

Mind Wide Open is more than a pandemic outreach project or a way to connect with the music community. Those things were important when Silver planned the series, but her target audience is much wider. She hopes to reach those dealing with pre- and post-pandemic mental health battles, educate listeners who don’t understand grief, depression, anxiety, and other conditions and advocates for accessible mental health services for everyone, no matter one’s socioeconomic situation.

Silver, now majoring in media studies and psychology, is no stranger to the mental health crisis. She has been in therapy since age seven for various challenges, and four years ago she lost her beloved father, Chris Cornell, to suicide. Those experiences inform the direction of Mind Wide Open, where she interviews her guests with empathy and courage.

“I’ve had the privilege of access to mental health resources,” she says. “I’m lucky to be in this position, and I’m aware that one of the most fundamental things that needs to change is the limited access to those resources.”

Her goal is to present candid discourse with her guests. “Infusing these conversations into our day-to-day lives and inner circles is what will de-stigmatize mental health issues,” she says. “Creating spaces where we're able to talk about it in an unfiltered, vulnerable, and honest way contributes to ending the stigma.”

A post shared by Lily Cornell Silver (@lilycornellsilver)

A photo posted by on

How did you know you were ready to do this?

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“It came less from a place of feeling ready and more from a place of, circumstantially and time-wise, feeling it was needed in the world, and in the U.S. specifically, for conversations around mental health, grief, loss, and suicide to be opened up, because people, myself included, were floundering, and I wasn't seeing conversations being had as much as they should have been.”

Hosting an IGTV series and podcast in which others tell you what they experience is a lot to carry when you are still in that place of grief and trauma.

“When it comes to grief, traumatic loss, and mental health in general, you go through periods of time when you're able to talk about it, and the next day you can’t. I don't know if I'll ever get to the place where I’m able to consistently talk about it every single day and not feel overwhelmed. It’s day by day.

When it comes to grief, traumatic loss, and mental health in general, you go through periods of time when you're able to talk about it, and the next day you can’t

“That's the timeline of grief. It's nonlinear. If people wait to talk about their grief and mental health when it doesn't affect them anymore, no one is ever going to have the conversation. Part of it is accepting that advocacy work is a very messy thing, and that's okay. That's how it's supposed to be.”

Are the interviews cathartic?

“Definitely. It goes back and forth between being healing and amazing to being overwhelming and feeling like it’s too much. Depending on who I'm talking to, sometimes it can be triggering. It very much depends on my own emotional state.

“Every year, around anniversaries, I'm in a heightened state of emotional reactivity. It's harder for me to talk about it, harder to form coherent thoughts, and that affects every part of my life. I get frustrated with myself: 'Why do I feel like I'm regressing? Why do I feel like suddenly it's so much harder and feel like it just happened?' My therapist always says, 'Your body remembers, and your body will feel it before your brain does.' Being aware of it and knowing that that's what I'm going through is important.”

How do you prepare for your shows and podcasts? Where do you draw the line in terms of subject matter?

“You don't have to air every single part of your private life and your emotional journey. Everyone has things they don't want to be front-page news. There's such a stigma around mental health that there are things we feel we can't talk about, and sometimes that's the thing someone wishes you would ask.

“I was a junior in high school when my dad died, and going back to school, so many people had no idea how to speak to me. They didn't want to bring up my dad, they didn't want to bring up where I'd been when I'd been out of school for a few weeks, and I wish someone would have talked to me about it. I wish someone had addressed it.

“I go into every interview with a pre-conversation and say, 'Is there anything you do or don’t want to talk about?' Everyone has areas of their life that they're not willing to delve into. Another weird thing about celebrity culture is that people feel entitled to every part of a celebrity's life, but everyone is human, everyone has parts of their life that are private to them. No-one is entitled to all of the information about somebody's life.”

What part does social media pressure play in mental health?

“The music industry is a unique but prominent example, and obviously that's where most of my foundational knowledge comes from when it comes to mental health. I've talked a lot about why mental health is such a ubiquitous issue in the music industry. Much of that is because artists tend towards sensitivity. What they create is so personal and raw and emotional, and to have that scrutinized as a thing for consumption, versus as a piece of art that they put their heart into, is in and of itself a damaging thing.

Artists tend towards sensitivity. What they create is so personal and raw and emotional, and to have that scrutinized as a thing for consumption is in and of itself a damaging thing

“I was very deliberate in wanting to put this series on Instagram as a social media platform, because there is a lot of consumption of unhealthy and damaging things for mental health on social media. If I can put something on people's feeds that is real, raw, vulnerable, and takes away that need for comparison, or something that people see themselves in, versus wishing they looked like something or someone else, then social media can be positive in that regard.

“There's so much that comes up on our feeds that we can't control. I've taken deliberate steps to limit what I'm consuming to things that make me feel good and make it safe and non-damaging.”

Something so important in the work you do is addressing grief and mental health. Too often we’re told to 'get over it and move on'.

“When my dad died, I was in such a state of shock, which is normal for traumatic loss or loss of any kind. But I was high-functioning – I was applying to colleges, taking the SATs, working in the music industry, and doing a bunch of stuff – and I was praised for that, which made me feel like, 'This is how I should be grieving. This is how I should be showing up.'

“It wasn't until nine months later that I started falling apart. I was in my senior year of high school, and the people around me didn't understand. We live in such a grief-illiterate society that people were like, 'It's been nine months; why can you not function? Why can you not turn in your homework? Why can you not show up to school every day?' I was finally at the point where the shock was wearing off and I was processing what had happened.

Grief stays with you forever, and it is not limited to losing a person

“When you grieve, you go through waves and different phases. I still go through periods where something comes up and I am thrown into emotion, and I feel embarrassed because I'm like, 'It’s been ‘this number’ of years since whatever it was happened. I shouldn't be upset about it anymore.' I'm embarrassed to tell my mom or my boyfriend that this came out of nowhere, and I don't want people to think I'm doing it for attention. But people feel that way because we don't talk about the parts of grief that happen years afterwards.

“Grief stays with you forever, and it is not limited to losing a person. You can grieve the loss of a pet, an experience, a period of your life, so many things. It’s something you process for the rest of your life. I appreciate that question, because I find myself having to explain grief to people through the lens of my own experience. Grief is not something we talk about openly, so it's an opportunity for me to educate people and hopefully help them gain a deeper understanding.”

You advocate for mental health and grief awareness, yet you feel embarrassed for falling apart.

“Right, and I understand that sometimes when I feel shame or embarrassment, it’s the conditioning I've had through my life and through growing up in a society that conditions us to have a two-week period where we get to decompensate, and after that you need to be on an upward trajectory.

“I can hold both things at once and know that I'm allowed to experience grief as it happens for me, and recognize that I've been conditioned to believe that I shouldn’t have big emotions and decompensate around it for years afterwards.”

Would you agree that terminology plays a part in creating stigma? Even the term “mental illness”, rather than “mental health”, plays into the stereotype of what people envision when they hear those words.

“We are conditioned to view mental health and mental illness as something reserved for a certain group or a certain type of people. What I try to convey is that every single person struggles with mental health at some point, and if by some chance they don't struggle with it personally, they know someone who does.

Stigma doesn't make sense to me, because mental health is a spectrum; it can look like so many different things

“That's why stigma doesn't make sense to me, because mental health is a spectrum; it can look like so many different things. It's not always the most extreme version, but the most extreme version also deserves attention and care, and doesn't deserve to be stigmatized.

“I do think terminology plays an important role in our societal conditioning. Terms like 'crazy' and 'psychotic', and saying things like, 'Oh, I’m happy and sad; I'm so bipolar,' or 'I’m upset that my kitchen is dirty; I’m so OCD,' absolutely add to the stigma around people who actually struggle with those conditions. This terminology has been ingrained in us because of our mental health illiteracy and our grief illiteracy as a society.

“As we talk about mental health more openly and have a greater understanding of these things, hopefully people will recognize how terminology and vocabulary either add to that stigma or help dismantle it.”

Will mental health awareness continue when people who dealt with it during the pandemic begin to feel better?

“I think the pandemic has blown the lid off a lot of issues that we can no longer continue to ignore. I don't think it's possible to go back to a place where we can pretend that people aren't struggling and suffering and that there isn't oppression. These are things we're going to have to continue dealing with, and coming out of this pandemic, it’s something that, unfortunately, more people will be in a position to understand.”

A post shared by Lily Cornell Silver (@lilycornellsilver)

A photo posted by on

You advocate for social justice, which ties into mental health and grief in many ways. How do you approach these important conversations?

“I will never understand what it’s like to be Black, to be a Person of Color, or experience what they have gone through – not just in the last year, but for hundreds of years. These issues are more prominent in the media, but they are nothing new.

“What I can do is use my platform to have people who have had those experiences speak on them and educate others. This goes back to empathy, understanding that you can’t understand, and that it’s time to truly listen. The only way things will change is if we have these open, honest conversations. We have to genuinely take in what others have to say and listen to how we can best be of service.”

Who are your dream guests?

“Billie Eilish and Selena Gomez. I've been a fan of Billie Eilish since the SoundCloud days. She is my generation’s version of what my dad and other musicians in Seattle were doing in the 1990s – that raw vulnerability and intense emotion. Singing about that openly and putting it into your art changed the industry. I love that she is an advocate for mental health and talks about her experiences.

“I'm also such a fan of Selena Gomez and all the work she does in the mental health space. I had the privilege to play a very small role in her Rare Beauty makeup line. The Rare Impact Fund has made an incredible pledge to donate so much money to mental health resources and funding. It's amazing to see people do tangible stuff like that, and I would love to talk to both of them.”

- For more information, head to mindwideopenproject.com.

Mental health resources

Alison Richter is a seasoned journalist who interviews musicians, producers, engineers, and other industry professionals, and covers mental health issues for GuitarWorld.com. Writing credits include a wide range of publications, including GuitarWorld.com, MusicRadar.com, Bass Player, TNAG Connoisseur, Reverb, Music Industry News, Acoustic, Drummer, Guitar.com, Gearphoria, She Shreds, Guitar Girl, and Collectible Guitar.

“The musicians, shops, and brands who use Reverb have always been at the center of all that we do”: Reverb has been acquired by two new investors – and will once again become an independently operated company

One of the UK's biggest guitar stores has sold its stock and website to online retailer Gear4music for $3.2 million – after weeks of speculation over its future

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)