Leslie West: "I wanted the biggest tone, and vibrato like somebody who plays violin in a 100-piece orchestra"

The life and times of a titanic presence in hard rock and a trailblazer for tone

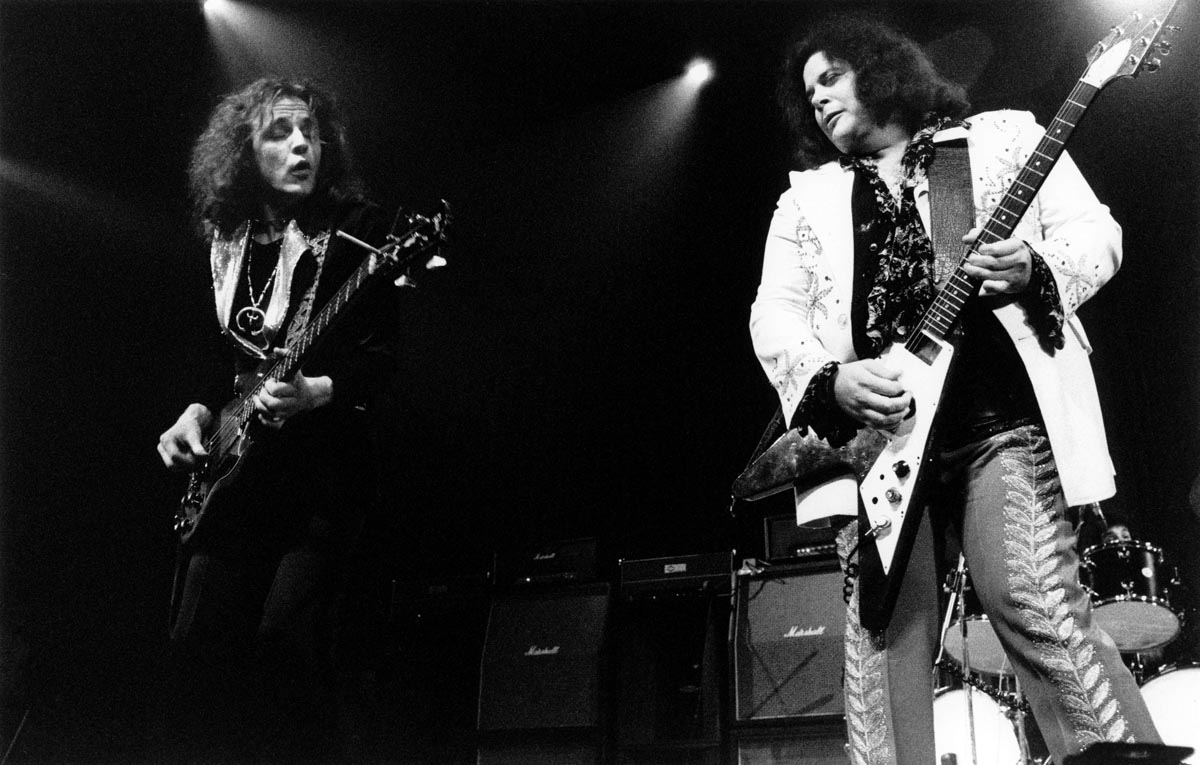

Leslie West always an unlikely guitar hero. His massive physical presence – he weighed 300 pounds at the dawn of the '70s – defied the longstanding vogue for undernourished-looking, rail-thin rock guitar slingers.

And he never cultivated dazzling fretboard techniques, relying instead on pure soul, a powerhouse singing voice, and one of the meatiest electric guitar tones ever to burst from a speaker cabinet.

“I didn’t play fast,” West said in 2011. “I only used the first and third finger on the fingering hand. So I worked on my tone all the time. I wanted to have the greatest, biggest tone, and I wanted vibrato like somebody who plays violin in a hundred piece orchestra.”

West, who died of a heart attack on December 22, 2020, at age 75, was a key architect of the heavy guitar aesthetic that coalesced in the late '60s/'70s and has been a staple of rock music ever since.

He was born Leslie Weinstein on October 22, 1945, in Forest Hills, Queens, and grew up in the suburbs of Long Island and New Jersey. He bought his first guitar with money from his bar mitzvah at age 13.

With his brother Larry on bass, he formed the Vagrants in the mid-'60s. The Vagrants were a soul-inflected rock band in very much the same vein as the Young Rascals – major hitmakers in that era – and the Hassles, the band in which Billy Joel started out, playing Hammond B3 organ.

The three groups worked the same club circuit in the metro New York area, and all drew extensively from the soul and R&B repertoire that record labels like Stax and Atlantic had brought to the fore at that time. The Vagrants scored a regional hit in 1967 with their version of the Otis Redding classic Respect.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

As a teenager growing up on Long Island in the '60s, this was my first introduction to Leslie West – and the Vagrants’ version of Respect was the one that garage bands like mine emulated. It was more hard-hitting than the Aretha Franklin version, and you didn’t need the legendary Stax horn section that played on Redding’s original.

This was something else again – Long Island garage soul, a kind of regional subgenre that flourished briefly and contained the seeds of greater things to come. Leslie West was destined to play a significant role in rock’s transition from the '60s to the '70s.

Ron Carey, who was Jimi Hendrix’s agent, was also our agent. And if they wanted Hendrix, they had to take us

Leslie West

The bridge from the Vagrants to Mountain was record producer/songwriter/bassist Felix Pappalardi, who first came to late-'60s prominence through his work with Eric Clapton’s emergent supergroup Cream. Pappalardi produced some tracks for the Vagrants and helped West formulate what was initially to be a solo project called Mountain. The name was a riff on West’s formidable girth.

He was enough of a showman to realize the value of turning what might have seemed like a negative body image (in today’s parlance) into a visual hook. When Mountain morphed from a self-titled 1969 solo record into a band, West said to Pappalardi: “There’s never been a fat and a skinny guy onstage. We can’t miss!”

West’s guitar style had evolved considerably by that point. In an interview with journalist Jeff Tamarkin, West credited American session ace Waddy Wachtel with helping him reach a new level of six-string mastery.

“I started listening to Eric Clapton and Jimi Hendrix and I said, ‘Whoa, I never heard anybody play the guitar like this,’” West recalled. “A friend of mine, Waddy Wachtel, lived in the same building as me in Forest Hills. He taught me how to play real guitar.” It was also Wachtel who sold West his first Gibson Les Paul Jr., an instrument that would become his signature axe.

He combined with Sunn Coliseum P.A. heads and cabinets to create his trademark chunky, sustain-rich guitar tone. Many people heard that gigantic sound for the first time at the Woodstock festival in 1969. Mountain were one of three “baby bands” to play at the historic event. The other two were Santana and Quill.

Of the three, only the latter was doomed to obscurity. Woodstock was just the third gig that Mountain had performed anywhere. They didn’t even have a record out at the time. “Ron Carey, who was Jimi Hendrix’s agent, was also our agent,” West told me in 2009. “And if they wanted Hendrix, they had to take us. And we actually got paid!”

From that muddy launch pad, Mountain went on to become a staple of '70s “album rock” radio. Their 1970 debut disc Climbing contained the classic track Mississippi Queen, boasting an iconic guitar riff that ranks up there with Smoke on the Water and Sunshine of Your Love as one of the bulwarks on which heavy metal was built.

The majestic, Jack Bruce-penned Theme for an Imaginary Western came from the same album, which was followed in short order by Nantucket Sleighride (1971), Flowers of Evil (1971) and the posthumous Mountain Live: The Road Goes On Forever, following the group’s disbandment in 1972.

West went on to work with his British hero, former Cream bassist Jack Bruce, and drummer Corky Lang to form the short-lived trio West, Bruce and Lang. This was followed by an equally short-lived Mountain reincarnation. Each of these ventures produced several studio and live recordings before calling it quits.

The problem was drugs – the downfall of many a great rock band. West spent the late-'70s and early-'80s getting sober. But soon thereafter he was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes – a common affliction of the obese. Struggles with weight and health issues would plague him for the rest of his life.

He conquered bladder cancer in the early 2000s, but in 2011 had a portion of his right leg amputated as a result of diabetic complications. By the time I spoke with him in 2009, he was well on his way to becoming a health-conscious family man. We had to wait until after the Passover holiday to do our interview.

Shortly thereafter, onstage at the Woodstock 40th Anniversary festival, he married his second wife, now his widow, Jenni Maurer. Throughout the decades he never stopped making music. There were solo albums, Mountain reunions and collaborations with artists like Bo Diddley, Ian Gillian, Ozzy Osbourne, Peter Frampton, Joe Bonamassa and others.

Frequent guest spots on Howard Stern’s radio show helped keep West in the public eye, and the drum intro to Long Red, a track from West’s 1969 solo album, has been sampled by numerous hip-hop artists, including Public Enemy, Jay-Z and Kendrick Lamar.

In 2006, Leslie West was inducted into the Long Island Rock and Roll Hall of Fame – a tribute to a local hero whose thunderous riffs are still echoing all around the world.

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.

The heaviest acoustic guitar ever made? Two budding builders craft an acoustic entirely from concrete because they “thought the idea was really funny”

“For years, the only 12-string acoustics I got my hands on, the necks always pulled off after a bit. I earned a lot of money replacing them!” Why one of the UK’s most prolific luthiers is a bolt-on acoustic die-hard

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)