The incredible story and decades of dedication that gave birth to Les Paul’s ‘Number One’ Goldtop – the solidbody guitar that changed the world

Les Paul’s son Gene tells the tale of Gibson's most famous electric guitar, beginning in the 30s with a mysterious hand-written note that changed the course of guitar history

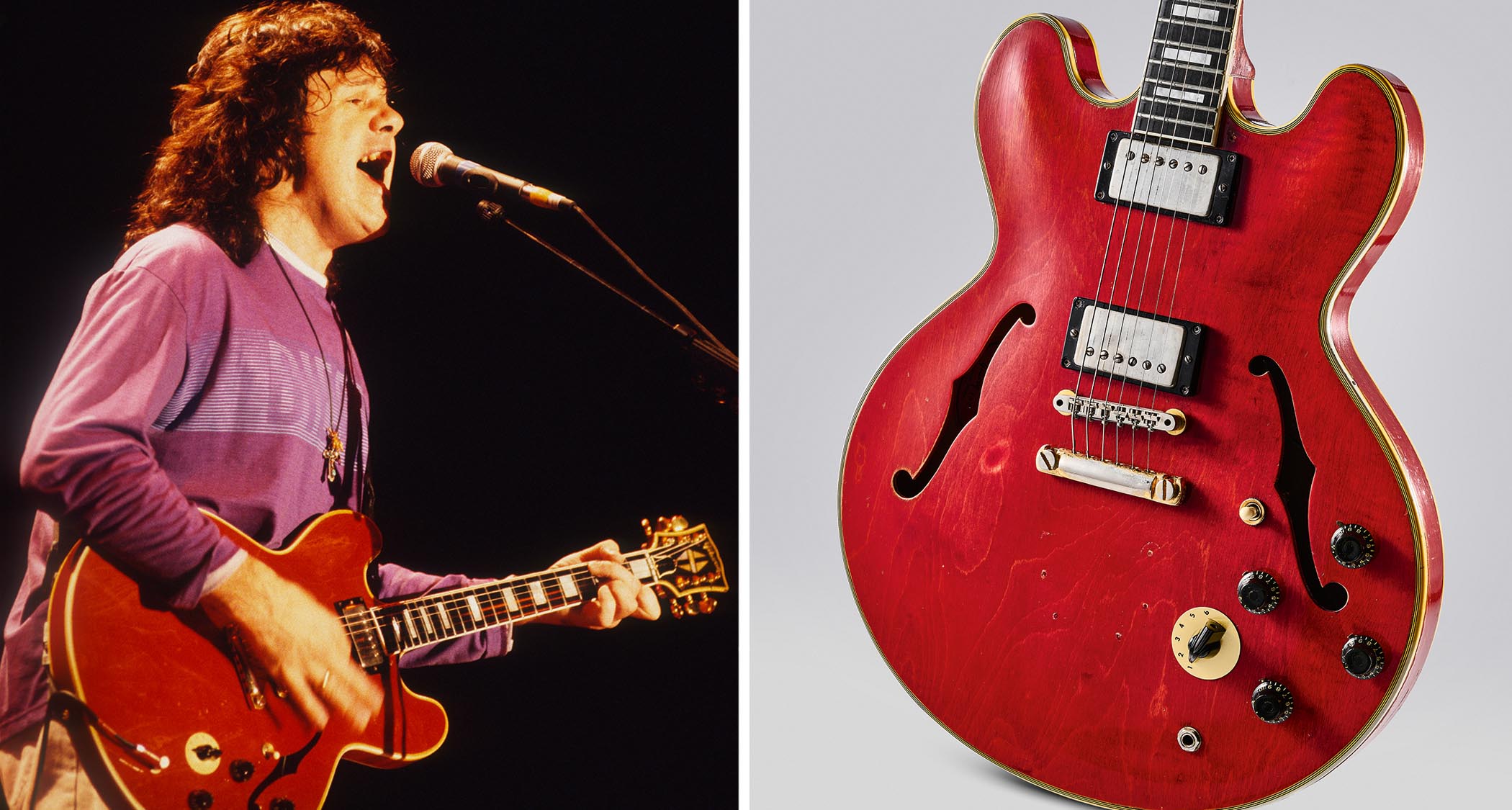

“The first time I saw that guitar, he wasn’t playing it,” Gene Paul recalls of his father Les Paul’s most cherished possession. “He asked me to go downstairs and get a specific guitar. And when I brought it back upstairs, it was in its case. And he said, ‘Put it right on the table there.’ And he said, ‘Open it up.’ And I opened it up – and it was this gold magnificent guitar, simple… elegant.

“I was just so struck by it,” Gene continues, “because I was used to the black Les Paul [Custom] guitar and the white one – the ones he usually used on stage and had in the control room. But he asked me to get this one and I brought it out. So I’m sitting there and looking at it and I asked him,‘What’s this?’ And then he sat down and told me a story…”

The story was no less than a full account of how Les battled for years to make his dream of a solidbody electric guitar a reality. A guitar whose voice could rise above a full orchestra and that summoned up the pristine sounds that Les, a Grammy Award-winning master of the instrument, could not achieve with the acoustic archtops he started his career on, back in the 1930s.

The guitar that the young Gene beheld in the case in 1959 was his father’s fabled ‘Number One’ – the first approved production model Les Paul to be presented to Les prior to the model’s launch in 1952.

To Les himself, this elegant guitar sitting in its plush case didn’t represent the beginning of something – but the triumphant end of a near-30-year struggle to make a dream that he pursued “obsessively” finally come true.

Now, for the first time, Gene Paul is ready to tell Guitarist the full story of how it all happened.

The First Stage

To tell that story, Gene explains, it’s necessary to go back to the beginning, when Gene was a child – when Les seemed, in some ways, not all that different to other dads. A trip to the theatre provided the first inkling that his guitar-loving father was, in fact, a major force in American music.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

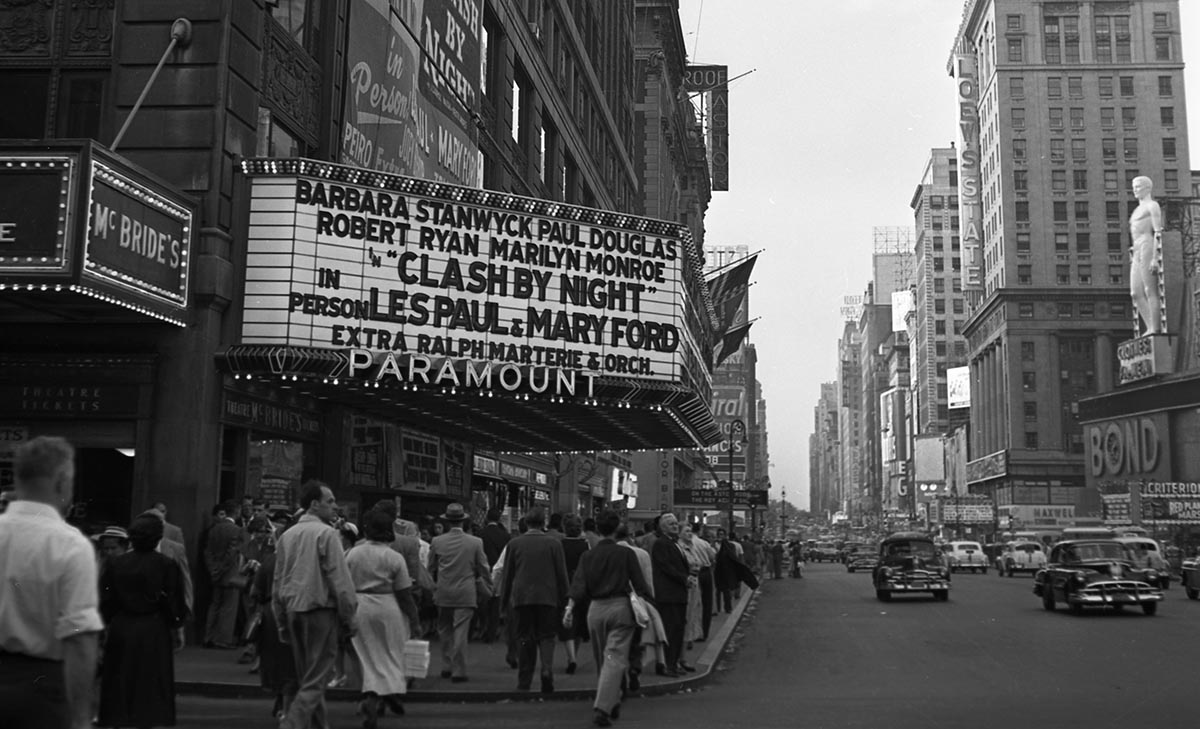

“My earliest memory of him playing guitar was in Chicago,” Gene Paul recalls. “I was living with my mom and I was about eight years old. Dad came to town with Mary [Ford] and they were playing at the Chicago Theatre and he brought me down to the theatre with them and I saw him perform there.

“He invited me out on stage to take a bow and gave me one of his guitars to carry. And that was one of those moments when I really figured out who he was.”

In the fame-obsessed era we now live in, it’s hard to imagine how a little boy would be unaware that his father was one of the leading guitar stars of his day – but, in fact, it was only when Gene became an adolescent and started taking an interest in music himself that he began to realise the extent of his father’s celebrity.

“I lived with my mom in Chicago until I was about 15, 16, around the late 50s,” Gene remembers. “And then my mom and dad decided that, okay, I was interested in drums and I was interested in music so it was time to go live with dad. So that’s when I went to stay with him on a permanent basis.

“I ended up on the road playing drums in the show. Until that time, I thought every father made his own guitars and had his own 8-track studio [laughs]… That was the environment I was living in, so I didn’t think any different.

“But when I got on the road, that was really the time when I soaked it all in and figured out that it wasn’t just a case of ‘father knows best’… I realised this guy was doing something else.

“I was in the band with him. I was playing in the orchestra when ‘Mary and Les’ were on stage. And I really got a sense of: ‘Wow, this is not my dad now,’ you know? People were coming up and asking for autographs and I saw him in his element. And that’s when I really started to appreciate the adventure of my dad’s life.”

Gene says that despite being a hugely gifted man who was as skilled at inventing audio equipment as he was at playing the guitar, Les didn’t brag – and, in some ways, he was so unshowy that even his own family weren’t fully aware of his achievements. Using the skills he learned in his father’s studio, Gene grew up to be an award-winning engineer and producer himself.

Joining Atlantic Records, Gene worked with legendary artists such as Aretha Franklin on many milestone albums. But, as he discovered one day, there were some classic records he knew nothing about, much closer to home.

“When I went to Atlantic Records and my own life went on its road, I ended up in mastering. One day, a partner of mine came into the room and he’s smiling and I’m looking at him like, ‘Okay, what’s funny?’ He says, ‘I got a project for you. It’s your dad.’ I said, ‘Really? What is it?’ He said, ‘It’s the early jazz recordings he did for Decca.’ I said, ‘Really? Never heard of that.’ And he said, ‘Yeah.’

“Now, Dad never played any of his early jazz stuff in the house, so I’m sitting there mastering this album, hearing it for the first time in my life,” Gene recalls.

“He played Django Reinhardt in the house, but he would never play his own early jazz stuff. And when I heard the album, I was just amazed. So he had his secrets. But this guitar happens to be the biggest one he ever had,” Gene says, his mind returning to the day when his father told him to fetch him his ‘Number One’ Les Paul, the day when Gene saw the guitar for the first time and learned how it came to be.

A Fateful Note

“It was around 1959 when he first showed me that guitar,” Gene recalls. “And when I first opened the case my dad said something that I didn’t understand. ‘The second time was the charm,’ was what he said, and I was sitting there trying to figure out what he meant. So I asked him and he said, ‘Well, you got to sit down and I’ll tell you about it.’”

Gene explains that his father then told him the following story. One day, back in the 30s, when Les’s career was just beginning, he played a gig at a barbecue stand. The gig itself was a workaday affair, but what happened afterwards changed Les’s life – and guitar history – forever.

“After my dad finished playing, this gentleman sent him a note,” Gene remembers. “It said: ‘I heard the voice great, I heard the harmonica great. But I couldn’t hear the guitar.’ And at that point in the story my dad stopped for a moment and said, ‘If there’s one regret I really, really wish I could fix, I wish I could have known who that guy was because that note is what made this guitar happen. Because after I got that note, I went home and started work.’”

In fact, the note started Les on a 30-year quest to make his playing heard properly that ended with the creation of one of the most famous guitars of all time. Disarmingly, that mission didn’t start with a direct approach to a major guitar maker – but with household appliances.

“Growing up, my dad was the type of a kid who would make do with what he’s got,” Gene says. “And his mother would let him do anything, so he felt free to do anything. He had a Sears and Roebuck guitar, which was his first guitar, and he wanted to amplify that a little bit to see if he could make people happy.

“So he got a hold of his mother’s phone and his mother’s radio and he figured out how to amplify the guitar a little bit. But he had something in his head telling him, ‘This ain’t it,’ you know? So he and a buddy went out looking for something that would be more solid [than an acoustic guitar body] and change the sound from an acoustic guitar to something that was in his head.And often he talked about that: he had something in his head. He didn’t know what it was, but he had a vision that he couldn’t clarify.”

“Anyway, they had a railroad track that went by the house and he and his buddy took a little wagon and went over to see if they could find something that was more solid than what his acoustic was made of.

“And they found a metal railroad track, a small piece, and they brought it back to the house and he rigged it so he could put his strings on it and then [connected it to] his mother’s telephone. And it turned out there really was a difference – and that was probably the next step in the evolution of this thing because he sat there and said, ‘Well, this is different.’

He tried stuffing his guitar with shorts, t-shirts, socks… anything he could find to deaden the response of the acoustic guitar

“But now, of course, he had to electrify it because it didn’t have any natural acoustics to it – it’s a metal bar, you know? But the fact it kind of worked intrigued him so much that he carried on from there.

“After that, he tried stuffing his guitar with shorts, t-shirts, socks… anything he could find to deaden the response of the acoustic guitar. And that kind of did something, but not enough. Then he went to the next step, which was plaster of Paris, and he put that in his guitar and that was even better – but it didn’t quite make it.”

The crazed vision of Les Paul pouring plaster into his guitar shows how feverishly dedicated he was to developing a solidbody guitar of some kind. But it took until 1938 for Les to find the ideal laboratory for his experiments in electric guitar tone.

Les had moved to New York by this point, Gene explains, and was looking around for a workshop in which to build his dream instrument. Handily, he came across a rising guitar maker that was willing to let him use its premises.

“Epiphone was in New York at that time and they had a shop, and Dad talked his way into it and made friends with everybody,” Gene recalls. “And so he started working with a four by four [plank]. And that became the guitar he called The Log.

“That was another real marker-point in his life because that was the first time he found something that didn’t weigh a ton but did provide what he was looking for in a solid type of a platform. So he put a neck on it and put his strings on it. By that time, they had some pickups going and he used those, too.”

With this crude but functional prototype up and running, Les decided to take The Log out to a gig – and there he made a discovery about guitar design that has held true from 1938 to the present day.

“He took The Log and he went to a nightclub and he played and nobody responded,” Gene recalls. “So he came back to the house and mom was there and she asked him what happened. And she was expecting a great response, but he said, ‘It didn’t go well – they didn’t respond.’ But, again, Dad was perseverance personified. I mean, this guy was never defeated. The cup was always half full… So he said, ‘Well, maybe it has to actually look like a guitar?’

“So he went back to Epiphone and he put the wings on it,” Gene says, referring to the addition of two curving sections of wood that were attached to the central ‘plank’ to lend The Log a regular jazz guitar’s outline.

“They didn’t change the sound at all,” Gene explains. “They just made it look like a guitar. So then he went back to the same club, same song, performed it again. Went home that night, mom asked him again and he said, ‘It went great,’ and she was so happy and he was really amazed by it, and he said to her, ‘I think I learnt something tonight,’ and she asked, ‘What’s that?’ and he said, ‘I think they hear with their eyes…’”

Now that The Log had proven itself at its first gigs, Les decided the time was right to approach a major guitar maker – and he chose Gibson.

“Gibson was First Class,” Gene observes. “I mean, they made not only guitars but they made mandolins. They made upright basses, they made cellos, violins. They had the whole nine yards covered. And Dad admired the woodcraft of the violins and all of those things. He really dug that.

“So he had his eyes on Gibson and he told me, ‘I wanted to take it to Gibson. I was ready. I had something. The Log went to the club, it worked, it was accepted… Gibson is going to take this and run with it.’ But, of course, they basically told him, ‘Thanks, but no thanks – have a nice day,’ you know,” Gene laughs. “And privately they even called it ‘the broom with pickups on it’.

“But Dad wasn’t taken aback by that at all. Not at all. He thought, ‘Okay, this is going to give me time to experiment some more, try some more ideas, and one day I’m going to put this guitar with Gibson and we’re going to make it together. I don’t care if it takes another 10 years, 20 years, I’ll wait and keep going.’ And that’s what he did.”

Failure, Then Breakthrough

Buoyed by the success of The Log on the live stage but hungry to improve his solidbody guitar concept still further, Les soon had another idea for making a breakthrough.

“Dad said that his next adventure was quite interesting because in 1941, after he took The Log to Gibson, he had a flash [of inspiration] while he was performing with The Andrews Sisters,” Gene says. “And the flash was: why not try aluminium? So he made an aluminium guitar and it was so innovative.

“It was great – and it was wonderfully odd-looking… everything was wonderful about it. It sounded good. So what could go wrong? Well, he’s on stage and of course, when he took his solo, they’d put a spotlight on them. And the heat from the spotlight changed the tuning because of the conductivity of the metal.

“So the only time he could play the damn thing would be in the dark [laughs]. But he still kept it. And it was marvellous. But the story was better than the guitar!”

Now several years into his quest, with some failures and a few successes to show for it, it would have been understandable if Les’s enthusiasm for chasing his solidbody dream had waned. But giving up wasn’t in his nature, Gene explains.

“I don’t think people understand what the hell this guy went through from getting that note at the barbecue stand till the time he finally got Gibson lit… Because this was 24/7. I mean, he once said to me, ‘Do you realise how many light bulbs Edison made before he found the one that worked?’

“He spent, what is it, close to 30 years on this before Gibson finally said, ‘Hey, we ought to try it, you know?’ So anyway, it’s now 1941, and he’s still sitting there thinking, ‘Okay, they hear with their eyes. Maybe what I should do is get a stock Epiphone.’ So he got a stock Epiphone and immediately put a metal plate in it. I mean, nothing was safe from him [laughs].

“But he called this guitar ‘The Clunker’ and he made three of these guitars from ’41 to ’46… But this guitar turned out so good that he didn’t touch it or modify it – and believe me, you had to put him in a straitjacket to get him not to modify a guitar because that was his whole being on the planet… But this guitar turned out so good it was the one that he used for Jazz At The Philharmonic and Bing Crosby. It was also the guitar he used on Les and Mary’s long run of hit recordings with Capitol. So now it was like, ‘Wow, I’ve really got something.”

The Birth Of ‘Number One’

After trying for so long to get the tiniest break, things now started to move fast. It was 1950 and Gibson had a new competitor in Fender, who brought the first solidbody electrics – the Esquire and Broadcaster – to market, confounding critics by scoring a hit with its new designs, which traditionalists had initially derided as ‘canoe paddles’.

Scenting change on the wind, the team at Gibson approached Les, Gene recalls, and this time they were all ears.

“Well, this is the time that Uncle Gibson knocks on his door and says, ‘Oh, by the way, you know, seeing as you have all these hits and you’re making all this noise with this electric guitar and Fender is getting hot on the heels… maybe we should talk. Are you interested?’ And before they finished the sentence, Dad said, ‘Let’s go.’”

This was the moment Les had referred to cryptically at the start of the story he told Gene in 1959 – the second time was indeed the charm, except this time round Gibson was coming to him.

The sense of validation and relief was huge, Gene says, and now Les could roll his sleeves up and embark on the work of creating something truly new with one of the greatest guitar makers in American history.

“Dad could finally take a breath and say he’s at the door and they’re not throwing him out,” Gene reflects. “But it still took two years of going back and forth after that [to get the guitar right] – he said that he got some guitars for approval that he couldn’t even play.

“He had big hands, so the regular neck wasn’t right for him and he needed that changed. And they did the bridge wrong… this was wrong and that was wrong. He went back and forth with these guys and finally he received a guitar that was right. And when he was telling me this, he looked at me and he said, ‘This is it…This is my Number One’.

“And he just had that little smile on his face and his eyes were wide open – he had a bond with that guitar, without a doubt, more than any other. And I’m not saying this because of the auction or any of that – as far as I’m concerned, my dedication is to his legacy. But this guitar was the one that meant quietly, personally, everything.”

Gene says that Les was grateful to Gibson and knew that he couldn’t have achieved his dream without their help – and willingness to listen to what he wanted from a solid electric guitar.

“He said to me, ‘I was so pleased with the fact that Gibson allowed me to do it my way. Because it had to feel right to me when I played it.’ And he was so pleased that Gibson allowed him to do that. And, of course, they had tremendous input with it, too – Dad never said ‘I did it all’…

“For example, Dad mentioned that Maurice Berlin [founder of CMI, which owned a controlling stake in Gibson] was the one who came up with the idea of having an arched top like a violin. Maurice said, ‘Would you be interested in that being on your guitar?’

“And Dad said, ‘Oh, man, I didn’t. know you could do that.’ So Dad was really pleased with the combination of everybody involved with it. But he really was honoured by the fact that Gibson believed in him enough to let him really make it to where it felt good to him playing it. And that was his moment.”

- Les Paul’s ‘Number One’ – the first guitar bearing his name to be approved for production – sold for $930,000 at The Exceptional Sale at Christie’s New York.

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.