Kings Of Leon: Kings Of Rock

Originally published in Guitar World, February 2011

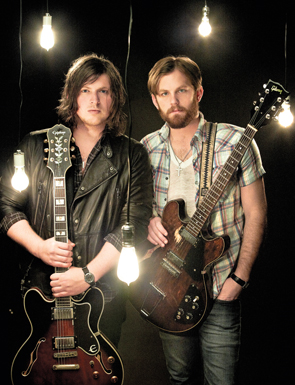

Their debut album barely made a dent in the U.S. charts, but seven years later, Kings of Leon have become the brightest lights in the rock and roll firmament. Caleb and Matthew Followill talk about putting creativity before skill when it comes to the guitar and songwriting—and ponder the real meaning behind “Crimson and Clover.”

On a Thursday afternoon in November, Caleb Followill, the 28-year-old singer and guitarist for Kings of Leon, is sitting in Guitar World’s New York offices and calling himself out. “I’ve always described myself as a bad guitar player,” he says defiantly. “I’m a two-string wonder. I don’t read tablature or anything like that. I don’t know a scale.” He cracks a wide grin. “Seriously. Pentatonic? No idea.”

The frontman is perhaps laying it on a bit thick. But the fact is, while he may not consider himself much of a player, Caleb and his 26-year-old cousin, Matthew Followill, seated just to his left on this day, hold down the six-string end for what is arguably the biggest band going in rock and roll. Two days prior to their Guitar World visit, Kings of Leon—which also includes Caleb’s brothers Jared, 24, on bass, and Nathan, 31, on drums—played a sold-out headlining gig at Madison Square Garden; a few days subsequent to our interview, they performed a mini-set in a jam-packed Rockefeller Center as part of a live broadcast for the Today Show.

Furthermore, in a time of exceptionally anemic record sales, the Kings’ fourth album, 2008’s Only By the Night, has moved more than six million units worldwide (going Platinum in a dozen countries), and boasted two of this young century’s biggest guitar-rock singles: “Sex on Fire” and “Use Somebody.” More recently, the Kings issued their hotly anticipated fifth effort, Come Around Sundown, which debuted at Number Two on the Billboard album charts and in its first two months of release has already sold upward of two million copies across the globe.

All of which indicates that, while Caleb and Matthew might not be burning exotic scalar runs and speedy sweep arpeggios across their fretboards, they’ve apparently mastered a considerably more difficult and elusive technique—the art of writing a powerful song. “We’re not really big guitar guys,” Matthew says. “But truthfully, for us it’s always been about coming up with a good tune rather than trying to make it all about the guitar part. That’s not what’s important. So maybe there’s always been a little thing where we’ve tried to not get too incredible at our instruments…”

“Yeah, right,” Caleb interrupts, with a hearty laugh. “Not too incredible…”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

One aspect of the band that is rather incredible is the Kings’ backstory. Their tale is an oft-told one, and rightfully so. It begins with Caleb, Nathan and Jared spending much of their childhoods in the back seat of a 1988 purple Oldsmobile, traveling the South with their United Pentecostal preacher father, Ivan Leon Followill, and being home-schooled by their mother, BettyAnn. Theirs was a world steeped in the sounds of religious and gospel music, and also one where rock and roll was strictly off limits.

Fast-forward some years later, to when the brothers, following their parents’ divorce, were living with BettyAnn in Nashville. There, Caleb and Nathan began performing as a country-singing vocal duo under the name the Followill Brothers, landing a manager and a publishing deal and hooking up with a local songwriter named Angelo Petraglia (who, today, along with Jacquire King, serves as the band’s coproducer). Petraglia took to schooling the Followills in classic rock—as well as sold Caleb his beloved workhorse instrument, a 1972 Gibson ES- 325—and also accompanied the duo on guitar whenever they would showcase their harmony-laden tunes for record labels.

In 2002, one of those labels, RCA, signed them up, which is when Caleb and Nathan called on younger brother Jared, back home in Nashville, and cousin Matthew, then living in Mississippi, and formed Kings of Leon. “A lot of bands, they start in a different way from how we did,” Caleb notes in something of an understatement. “They get together and start playing and become friends later. But we were family from day one. We always had this thing about us.”

That thing has continued to evolve through the years. Since debuting in 2003 with the Holy Roller Novocaine EP, Kings of Leon have progressed from a group of scrappy, southern rock–influenced longhairs into an expansive and somewhat more refined arena-shaking force. Much of that transformation has come courtesy of the various sonic textures and effect pedals that have served to color and modernize what is at heart a classic approach to songwriting.

Matthew says, “I think that the first two records we made [2003’s Youth and Young Manhood and the following year’s Aha Shake Heartbreak] were kinda dry, with a really raw sound. And for the next one [2007’s Because of the Times] we thought, We gotta make a change. We try to keep up with the sounds around us, and it seemed like the time to add some things. So I went and bought a Boss ME-50 [multieffect processor], and when I got home and started playing around with it, I was like, ‘My lord, we can go so much further with all these sounds.’ ”

This updated version of the Kings debuted on Because of the Times, which garnered the band greater mainstream recognition through singles like the ethereal “On Call” and the bass-heavy rocker “Charmer.” But it was the follow-up, Only by the Night, that broke things wide open. “We had already done four albums by that point, but when [success] came, it hit really hard and fast,” Matthew says. “I guess there’s no real explanation for it other than you have to have a big hit on the radio to be popular in America. And that’s what happened with ‘Sex on Fire’ and ‘Use Somebody.’ We had a few hit songs, and that made people say, ‘Who’s this band?’ They went and checked out our other music, and I guess some of them liked it, and the next thing you know we’re selling out Madison Square Garden.”

But the still young band are primed to keep pushing forward. On Come Around Sundown, they continue to delve into new stylistic territories, including slow-burning, Fifties-style rock (“Mary”) and angular, echo-laden post-punk (“Pony Up”). At the same time, they reach back to tread rootsier ground, as evidenced in the relaxed country vibe of “Back Down South,” featuring Matthew’s lonesome lap-steel playing, and first single “Radioactive,” which floats along on a U2-ish single-note line but pivots on an uplifting, distinctly gospel-infused chorus hook.

For his part, Caleb credits the new album’s range to the fact that all four Kings now take an active role in the songwriting process. “It’s definitely more collaborative than it used to be,” he says. “And as a result I think my favorite songs on this album aren’t Matthew’s favorites, and Matthew’s aren’t Nathan’s, and Nathan’s aren’t Jared’s. But we’ve been going harder than any band that came out when we came out, no question about it, so at this point there’s no way of denying one another his own voice. So while I may not love every song we’ve ever written, I’m definitely proud of everything we’ve ever done, and of how hard we’ve worked to get here.”

It’s a work ethic that has been present since their earliest days. “In the beginning, we practiced ruthlessly,” Caleb continues. “Every day, three times a day. I remember I had read something about Lynyrd Skynyrd where it said they would go to, like, the hottest little barn or shed they could find and just rehearse and sweat. So we would get all dressed up in warm clothes—I’d put on these big wool sweaters—and sit there and kill it as much as we could. Then we’d take a little smoke break, come back and just keep going.”

Adds Matthew, “And we’d get whoever was in the house at the time to come down and listen to us.” He gestures to Caleb. “Their mom, she’d be like, ‘That sounds good. A little demonic, but good…’ ”

In a wide-ranging interview with Guitar World, Caleb and Matthew spent considerable time reflecting back on the Kings’ formative days, and discussed their unusual musical upbringings, their approach to guitar playing and songwriting, and how a band of brothers—and a cousin—became the biggest act in rock and roll today. One clue? Their distinctively unschooled guitar styles. Says Caleb, “I’ve had people come up to me and ask, ‘What are you playing for that part right there?’ And I’ll be like, ‘I have no idea. You’ve got as much chance of figuring it out as I do.’

“But,” he continues, “I will say that creatively, and even skillfully, at times we’re better guitar players than a lot of people that learned everything the right way from a teacher—only because we do things a teacher doesn’t know how to do. So it’s not all about skill; it’s also about creativity. We do it our own way.”

GUITAR WORLD Considering the band members' upbringing, you didn’t grow up immersed in the sounds of classic rock radio, MTV, all the music that we have come to regard as standard-issue fare for rock musicians. Has that had an effect on how you approach writing your own songs?

CALEB It has, and I think it’s aided us. I don’t like to say bad things about bands, because everyone has a different road and they travel it in different ways. But I can remember watching TRL [Total Request Live] on MTV when I was 16 years old and it was like, Limp Bizkit, Britney Spears, Korn, *N Sync, Eminem. And I was like, Man, I don’t get it. ’Cause I was still listening to the oldies. I was still catching up. I was listening to early rock and roll and doo-wop. I would even listen to big-band music. I loved that stuff. I thought it was so romantic, so beautiful. And obviously I had a gospel past, and so I didn’t get what was going on in new music.

MATTHEW I think that’s why we sounded the way we did on the first and second records. We hadn’t heard a whole lot of the music that most people had been listening to their whole lives. I remember when we first got together, they all played me the Led Zeppelin box set and I was like, “Holy shit! What the hell’s going on here?”

CALEB [puts hand above head] Yeah, that’s because we also had a bag of weed like this tall.

GW A lot of your early exposure to rock music came from your songwriting partner, Angelo Petraglia.

MATTHEW Yeah. We’d go over to Angelo’s house and he’d be like, “You gotta listen to some Rolling Stones, man.” And we were like, “All right, yeah, we’ve been hearing about them our whole lives, cool.” So he turned us on.

CALEB The thing that was great about Angelo was that, with something like the Stones, he’d start by playing us the early stuff, and then we’d work our way into everything else. Which was beautiful. It was the most amazing way to listen to it because it was like hearing it the way it happened.

GW Early on, particularly with Youth and Young Manhood, critics would point to various classic and southern rock bands when describing your sound. Was it often the case that you found yourselves being held up against bands you had never really listened to?

MATTHEW Yeah, it was weird. We were from the South, so everybody would call us southern rock. But no one had ever shown us an Allman Brothers record, or a Lynyrd Skynyrd record. Of course we knew, like, “Sweet Home Alabama.” But we didn’t go out and base our whole record around one song from a band. So all the reviews would say, “Skynyrd and the Allmans and a little bit of the Strokes.” But we really weren’t trying to be anything. We just wrote songs, and that’s the way they came out.

CALEB For me, when people would mention Lynyrd Skynyrd, I’d be like, “ ‘Tuesday’s Gone’…from Happy Gilmore!” Swear to God. That’s what I knew of ’em. “That band with the song in Happy Gilmore? I love that fucking song!” That’s how I associated things. But then on the other side, when I would tell people the music I actually did listen to, they didn’t believe me.

GW Such as?

CALEB Tommy James and the Shondells. People would look at me like, “You’re tryin’ to be cool, tryin’ to be different.” But seriously, “Crimson and Clover” is the song that made me want to get into music. And that’s because all I listened to was oldies. For a long time “Stand by Me” was my favorite song ever. [turns to Matthew] And who was that one band… Coverville?

MATTHEW No, Storyville.

CALEB Right, Storyville. They did a cover of Sam Cooke: [begins to sing “A Change Is Gonna Come”] “I was booorrn by the river...” And we learned that song from Storyville, which was like a Nineties blues act that sang the shit out of it. [The Texas-based band featured Double Trouble drummer Chris Layton and bassist Tommy Shannon.] And then we went back and heard the original version. So we would discover music in a weird, strange way, just whoever played us something that we could listen to. We’d be like, “All right.”

GW So where did you hear Tommy James?

CALEB In the back seat of a Toyota Corolla, driving home from school with my uncle Larry. He would put on the oldies station. He was a preacher, but I guess he thought oldies were okay to listen to. And one day “Crimson and Clover” came on. I was like, 14, and I heard Tommy James go, [sings in a low voice] “Crimson and clover…” And I went, “Oh my God, this is the greatest song ever.” And my Uncle Larry, he looked at me, and he said, “You know what this is about, right?” I said, “Uh-uh, no.” And he said, “It’s about a guy taking a girl’s virginity. The blood and the clover, he takes her virginity in the grass.” And I was like, My God… And that year for my birthday he got me a cassette of Tommy James and the Shondells. And I learned “Crimson and Clover” and “Crystal Blue Persuasion” and all the other songs on there.

GW Similarly, when the band first got together, you guys weren’t exactly practiced musicians.

MATTHEW I started playing guitar when I was, like, 12 years old, and after a while I quit. And then around 17, Jared started calling me, saying, “You should play guitar for the band.” And I was like, “Well, shit,” and I bought a guitar and started playing again. But I learned some stuff. I used to buy Guitar World all the time. That’s one of the ways I learned how to play, by the tablature in the back.

GW Caleb, as the story goes you picked up guitar right around the time you began writing songs.

CALEB After, actually. It was actually a crazy thing. I was writing songs with this guy in Nashville who was a massive Dylan fan. And I was a lyricist. I could go in there—I didn’t need to have an instrument or anything—and I could give you a melody, I could give you the words, all of it. And one day I was humming something to him, and he picked up a guitar and just started playing my melody. And I was like, “Man, that’s amazing. I wish I could play guitar.” And he said, “Enough to practice? You wish you could play, enough to really want to learn how?” And that really sunk in. I thought, He’s right, you know? You’re never gonna really learn if you don’t try.

GW So how did you go about learning to play?

CALEB Well, when I did finally pick up a guitar, I already knew how to write a song. But I also knew that I had a very particular kind of song that I wanted to write. So I would hum it to myself and then I would find the notes. I remember going to a buddy’s house and listening to him play a Beatles song on guitar. And he hit this one chord, and I looked at it, went home, dissected it and played it five different ways and came up with “Wicker Chair” [from the Holy Roller Novocaine EP]. Then I saw him the next day and I watched him play a barre chord, and I went home and grabbed my guitar and I went, dummm da dum da dum da dummm. And my little brother Jared, who was like 14 at the time, came home from school and I played it for him. I said, “Do you think kids at school would think this is cool?” And he was like, “Yeah, I think they’d think that was cool.” And that was “Molly’s Chambers” [from Youth and Young Manhood]. So I would try to figure out stuff out as I heard it in my head.

GW This was before or after you signed to RCA?

CALEB This was before. So I was playing a little bit. Un poquito. Not great. Not great enough where I was comfortable playing for a label. So me and Nathan, we had Angelo with us when we would go around and sing for the record companies. He knew the songs because I would go to his house and be like, “Look, I got an idea,” and we would sit there and I would play what I had for him. But I was a very slow player. It would take me a second to get from one chord to the next.

GW And Jared didn’t play at all when he joined on bass.

CALEB Nothing. He never touched anything. He was, like, 15, and he had the worst timing of anyone in music at that point. Like, he couldn’t clap on beat. But he started learning the scales and stuff like that, and he picked it up.

GW What do you recall about the first Kings of Leon show?

CALEB [smiles] It was awesome.

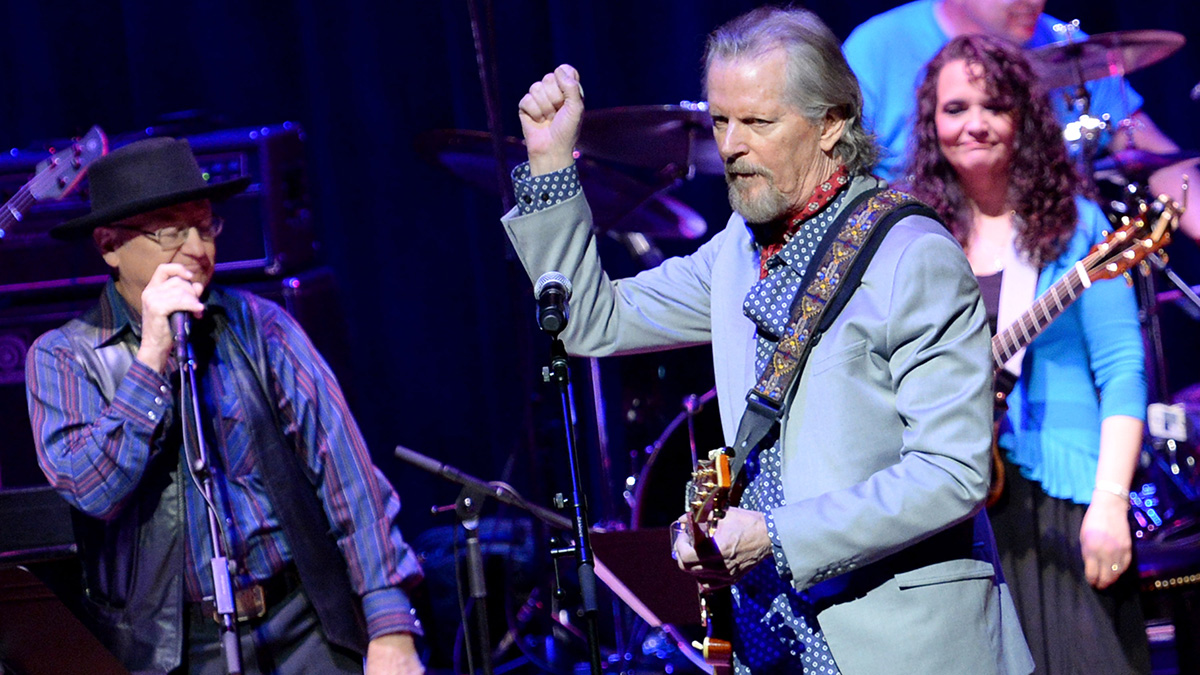

MATTHEW I was so nervous, but it was great. We opened for Billy Joe Shaver. The Skeeters played after us. It was in this place in Atlanta, Georgia—Smith’s Olde Bar.

CALEB We went out there at Smith’s Olde Bar, and it’s all cowboy hats in the crowd. So I said, “Let’s country it the fuck up. Play it as fast and as countrified as we can.” We went out there and did it, and cowboy hats were being thrown in the air. They loved it. So then the curtain closed, and I remember we all turned around and did a big group high-five—this kinda 90210 moment where we were like, Yeah! [laughs] And then we went out there to watch the next band… And we noticed that the curtain was see-through. Everyone saw us do it.

GW Though you started out playing in a very raw style, over the past few albums the use of effect pedals has become a defining quality of the Kings of Leon sound. Did that interest at all stem from the band’s time opening for U2 in 2005?

MATTHEW I’m sure it did. But a huge part of it was that right after that we went on tour with a band called the Secret Machines. Their guitar player, Benjamin Curtis, was so creative with his pedals and that was one of the things that sparked it. Everything he did sounded so badass. That was what led me to get the ME-50. We were writing Because of the Times then, and it just opened everything up.

GW For the new album you chose to record for the first time in New York. Why?

CALEB We just knew we wanted to switch it up. The last two were in Nashville, the two before that, in California. We didn’t want to get in a comfort zone. So at first I was like, “Let’s go to the country, or some place in upstate New York, maybe Woodstock, where we can all just kind of live in a house together and live the music.” And then my little brother Jared, he was newly single at the time, and he was kinda sweatin’ it…

MATTHEW Let’s be honest: The whole reason we did it in New York City was so Jared could go get laid.

CALEB He was just kinda like, “Well, what am I gonna do?” And I said, “That’s why I think upstate is good, ‘cause you can go into the city every weekend and get your fix. Drive down, take a helicopter, whatever you wanna do. It’s your money, you spend it. And then, the more he talked about the city, the more we all talked about it, I thought, “Well, maybe the pressure of New York City would be a good thing. And I will say that I imagine we got more work done doing it in the city than we would’ve somewhere else. Because other than maybe occasionally eating lunch with our ladies or grabbing a midnight drink, we were in the studio.

GW How do you guys work in the studio?

CALEB Me and Matthew were always the first ones there and the last ones to leave. We enjoy the creative process—all of us do—but I think Nathan and Jared, they have a tendency to go in there, get their work done, and go home. Just like when we were kids. We were all homeschooled, and Nathan and Jared would be outside playin’ ball and I’d be lookin’ out the window watching ’em because they had done their homework early, and I’d be sitting there at 10 at night not finished.

GW Matthew, you take some pretty ripping solos on the album. Like the one in “Mary,” for example…

CALEB That one and the one he does in “No Money” are my two favorite solos of his on the record.

MATTHEW [to Caleb] I think they’re the only ones on the record, bro.

GW Are they improvised?

MATTHEW Yup. Both of those were live in the studio, one take, and I was so mad because I wanted to do more.

CALEB He always hates them, and we’re all like, “That’s perfect!”

GW In that respect, it’s my understanding that opinions of songs among the band members is a push-pull situation, with Caleb and Nathan on one end and Matthew and Jared on the other.

MATTHEW That’s the way it’s been talked about. I guess it’s true in a way, just ’cause, sometimes it is the younger guys on one side and those two on another—

CALEB [breaks in] Yeah, two real immature guys and two very mature guys.

MATTHEW But that said, I feel when we’re in the studio that it’s absolutely four guys working together. I don’t ever think it’s, like, Caleb and Nathan scheming against us. Basically we all have a couple songs that are our favorites and we fight to work ’em in. But even though everybody has slightly different musical tastes, we all like the same stuff to an extent. Caleb loves his country stuff, and even though it’s not what I listen to all the time, I appreciate it.

CALEB But I think that’s why it works. You’ve got Jared pulling from a younger point of view and trying to get his music played in a club where he can get laid, while Nathan pretty much just walks in and does his job. Me, I’m very lazy with my music. With me, it either rips, or it’s country, or it’s gospely, or it’s got a good lyric. I’m not too hard to figure out. Also, when I see things going too well, it scares me. I want there to be some kind of confusion and some kind of “I hope it’s gonna work…” To me that’s real music. And Matthew, I don’t wanna speak for him, but he can hear a song and know when it’s gonna be a hit, or when it’s gonna be this or that. And so he’s my biggest fear. When he says, “That’s a hit,” then I go, “Fuck!”

MATTHEW Probably the reason I can tell something’s gonna be a hit is because Caleb will come in and, whatever song is my favorite, he’ll go, [mumbles] “Man, I don’t like that. That one can’t go on the record.” And I’ll be like, “Bro, that’s one of the best songs. Just chill, we’re only halfway there. Just wait.” And by the end of it he usually comes around.

CALEB Yeah, and then we have to go and play it on the fuckin’ Today Show.

GW I assume you’re talking about “Use Somebody.”

CALEB Well, look, I knew the potential of that one, at least in the sense that—and no offense to the rest of the song—the lyric itself I knew was something a lot of people in the world could relate to. Because no matter if you’re successful or unsuccessful, if you’re male or female, this or that, there’s always that point in everyone’s life where they could use a hand and use someone to be there for them and let them know what they’re doing is okay.

MATTHEW And then of course the music really sticks in your head. I hadn’t heard the song in a while, and the other day it came on somewhere and I thought, Wow, it’s really pretty catchy.

CALEB Then you hear, like, a million people cover it on fuckin’ YouTube and you’re like, “All right, I get it.” ’Cause I remember when the White Stripes came out with “Seven Nation Army,” and after a while it was like, “I hate this fuckin’ song!” ’Cause every DJ was spinning it and every band was covering it. But then, as soon as it stopped being played, I heard it on the radio again and I was like, “I love this fuckin’ song!” So love it or hate it, I guess “Use Somebody” is gonna be that song for us, whether we like it or not. And that’s okay.

“The rest of the world didn't know that the world's greatest guitarist was playing a weekend gig at this place in Chelmsford”: The Aristocrats' Bryan Beller recalls the moment he met Guthrie Govan and formed a new kind of supergroup

“We hadn’t really rehearsed. As we were walking to the stage, he said, ‘Hang on, boys!’ And he went in the corner and vomited”: Assembled on 24 hours' notice, this John Lennon-led, motley crew supergroup marked the beginning of the end of the Beatles

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)