Soundgarden's Kim Thayil: "Badmotorfinger was our interpretation of the heavy, dark and psychedelic things we liked in music"

On the 30th anniversary of the band's seminal album, the Soundgarden guitarist reveals the origins of his unique sound

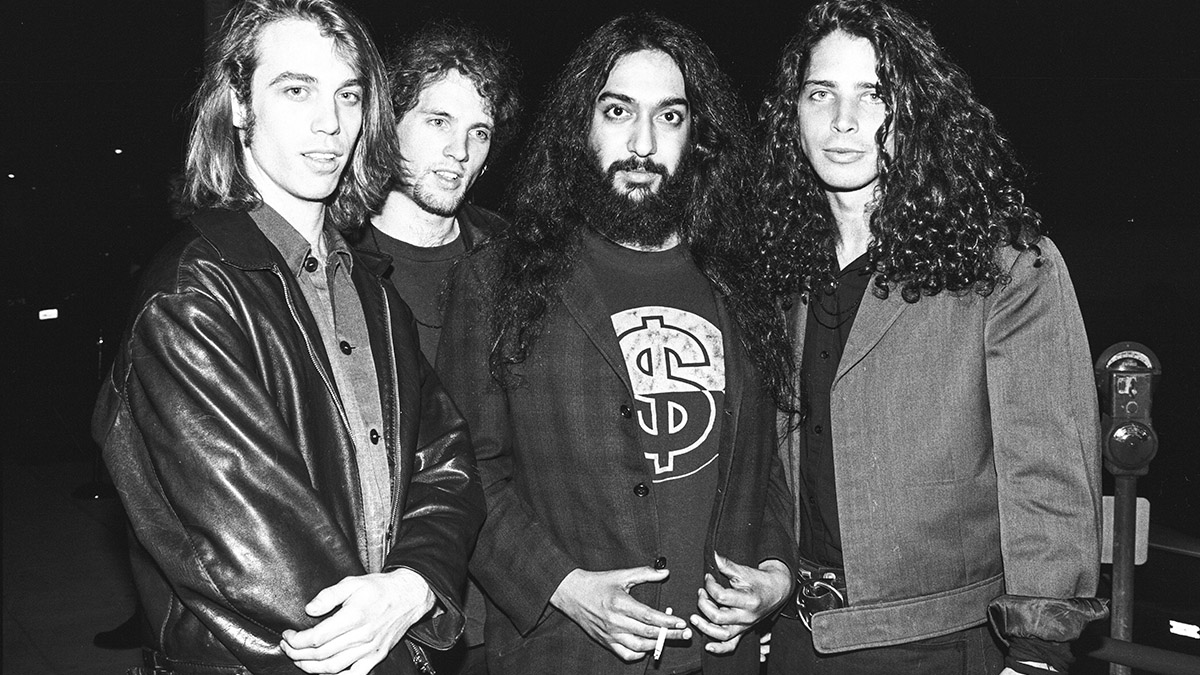

In 1991, three albums by Seattle bands had a seismic effect on the sound of rock music – Nirvana’s Nevermind, Pearl Jam’s Ten and Soundgarden’s Badmotorfinger. Like punk before it, grunge was a revolutionary force, and Soundgarden, the first of those bands to sign to a major label, played a leading role as architects of the ‘Seattle Sound’.

Badmotorfinger was the band’s third album and the first to feature the classic line-up of Chris Cornell (vocals, rhythm guitar), Kim Thayil (lead guitar), Matt Cameron (drums) and Ben Shepherd (bass).

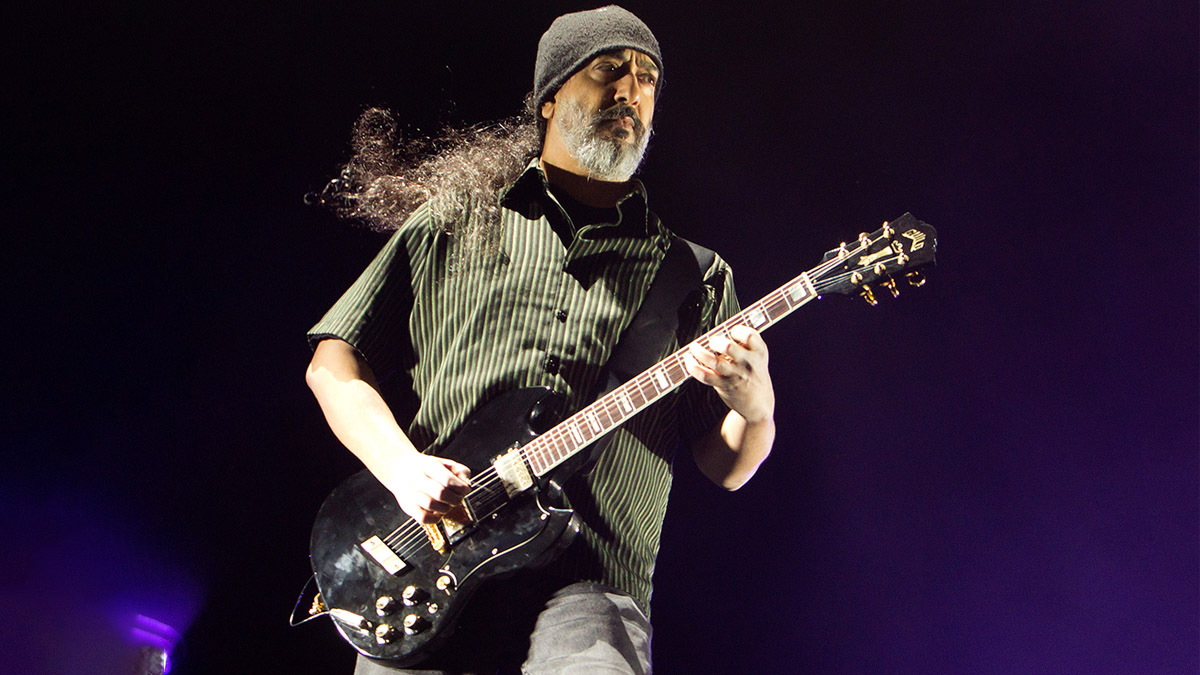

It was also the heaviest of those three era-defining albums of 1991 – with Thayil delivering screaming leads and scorching riffs, and combining altered tunings and odd-time meters into his own church of psychedelic noise.

30 years on, as Thayil speaks to TG from his home in Seattle, his thoughts are focused on the album that stands tall as the pinnacle of Soundgarden’s career – a career which ended, tragically, with the death of Chris Cornell in 2017.

Most of all, he remembers the fun that he and Cornell had working as a two-guitar team. But in an hour-long Zoom call, the conversation turns to all things six-string-related.

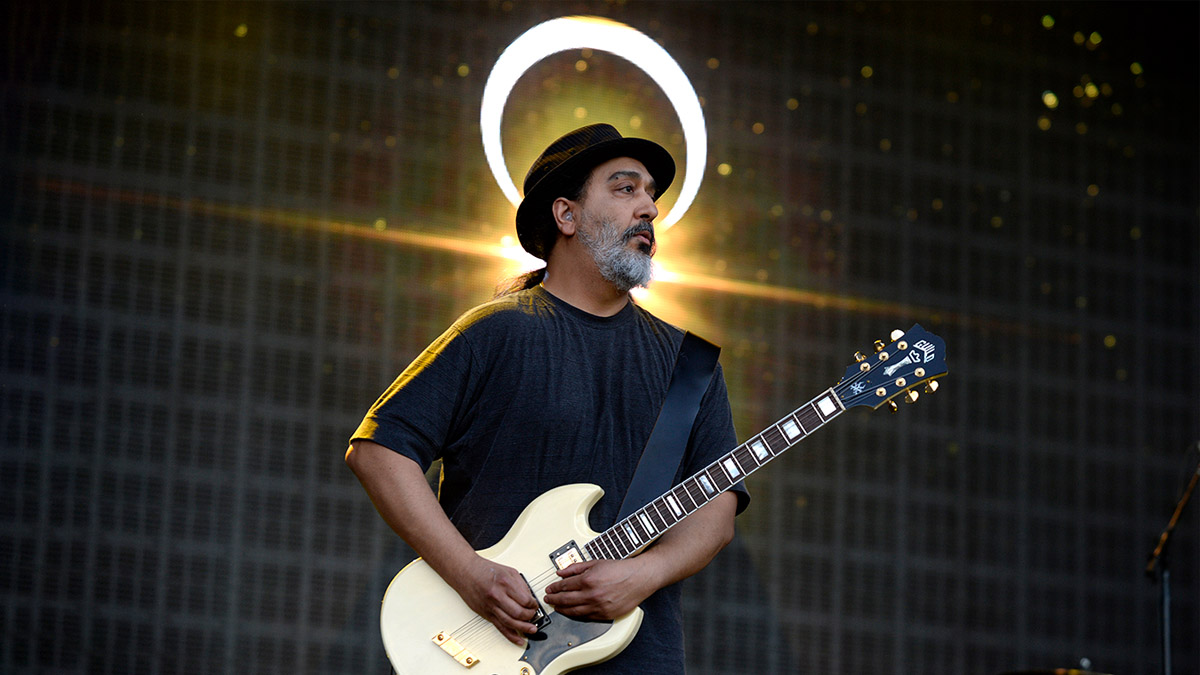

First, he offers an apology. “I’ll try my best for you,” he grins from behind his white wizard-like beard. “But I must admit, I fail to be on a first-name basis with my gear. I can probably come up with the general make and then the specifics somehow elude me!”

Even so, he has plenty of sound advice to pass on – beginning with how an “affordable” guitar was pivotal to his development as a self-taught player.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You’ll know when you find the right instrument for you...

”Unfortunately, I don’t think this advice is given to younger guitarists. Get something that feels good to play. Don’t buy a cheap guitar that’s tough to play. It is discouraging. It will take you longer to learn those chords. You want something that will facilitate your learning and give you the rewards to encourage you to go on.

”The S-100 is the guitar I bought when I was 18, and ultimately was the one I could afford to buy. I had started playing a few years before that, when I was 15. So at that stage I was learning new techniques and getting better gradually, as I was self-taught. But I had to buy a guitar that I could afford.

”And the Guild S-100, which I bought in ’77 or ’78, was pretty affordable. It only cost me $250, which was way less than a Les Paul or Strat. I think friends would have directed me to those other guitars, but this one looked good – it was black – and it was in good condition with great action. When I picked it up, I found that it was easy to play and had a fast neck.”

Embrace the peculiarities of your chosen instrument...

“There were things about the S-100 that I didn’t fully understand. I didn’t really know what distinguished it from a Les Paul or a Strat. By learning on that guitar, my style developed. It was how it made me play and what it allowed me to do.

“Weirdly it had a microphonic pickup – I could blow on the strings or talk into it and that would get picked up. Consequently, I would get this weird feedback and hum – which I would probably discourage, because the people you play with might not want to hear your guitar screaming or humming away. But I did! So eventually that would become a component of what I’d do in Soundgarden.

“It seemed to voice really loudly beneath the bridge. There’s this good space between the bridge and tailpiece where I can hit the strings and strum it to get this ‘krring’. I noticed I could do that on the headstock, though some of my friends’ guitars didn’t do that.

“I liked the fact I could make these weird noises with my guitar and my fretting hand adapted to that guitar, with a slightly thinner neck and lower action. I felt familiar and comfortable with it. That’s how it came to be my main guitar.”

See what you can do with similar models from the same series...

“I also started playing Guild S-300s, which came with DiMarzio pickups. I was learning about how guitars got that big, distorted sound – was it the amp or the instrument? I was led to believe it was the guitar and perhaps also the pickup.

“All these guitarists I knew would talk about DiMarzios. So I saw this advert for an S-300, which looked a bit cooler than the S-100, a little more electric. And the ad said it came with the Guild pickups – just like on my S-100, which I knew I already liked – or two different DiMarzios, a PAF in the neck and Super Distortion in the bridge.

The Guilds stay in tune – that’s another great thing. They come stock with Grover tuners, which hold up perfectly for all the weird tunings we used

“I thought it sounded like a cool guitar and decided to get one. But I never saw them in stores. I came to learn that sometimes guitar manufacturers would run ads just to test the markets. They may not have had a factory production going; it may have just been some demonstration models.

“I guess they’d do it to bring product awareness to their brand and different lines. So these S-300s weren’t fully in production and made for test markets. Chris Cornell and Ben Shepherd really liked the sound of those guitars, because they were a bit beefier than the S-100. They didn’t play the same way.

“The strings didn’t move as much if I was to bend behind the neck or tailpiece. They played more like a regular electric guitar, and didn’t have the weird feedback thing. But it was a nice solid sustain and very warm, which is why it ended up in the set for certain songs.”

Always go with what serves the song best...

“I played some Gibson ES-335s on [2012 comeback album] King Animal, but I was kinda forced to. The band, the crew, the producer... They all wanted me to have other guitars in my rig for different voicings. And that made sense. We’d travel with a dozen or so guitars because of all the different tunings.

“We tried it the other way when we were goofy and naive. We’d take a break in between songs and change the tuning, which was terribly demanding of the attention of our audience! With techs and a bigger collection, you can swap guitars and you’re ready to go in an alternate tuning. So, get a Firebird, because you played it on this song so it works well there.

“I used a lot of Teles on the Down On The Upside tour. I don’t use them as much anymore. Because of the bridge and how they’re made, they’re great for standard tunings but I don’t find them great for some open-tunings like C or G. The Guilds stay in tune – that’s another great thing. They come stock with Grover tuners, which hold up perfectly for all the weird tunings we used.”

Thicken your guitar parts for more motion...

“I always liked using multiple guitar tracks. Whatever I play, I like to double it with another track, doing that on different parts for colour. And then Chris started doing that, so it’s tough to tell who is playing on that album. If you hear two guitars, both could me. Or a couple of me, and a couple of Chris. Or one of me and one of Chris... Or even five each! It would depend on the song.

“There were a number of tracks that Chris didn’t play on – usually the faster songs or maybe a riff I wrote that was more difficult for him to play. In those cases, you might hear three or four guitars and they’re all me. We liked thickening parts so they were slightly out of sync. That would bring a cool motion to it.

“I heard Led Zeppelin doing it and even some hardcore bands like Minor Threat. And that made me think about not making things perfectly in-sync, and try to get two unique performances that are naturally a little bit out. It’s not the regular sweep of a delay effect or modulation effect, it’s an irregular sweep, which is a little bit more trippy. I liked that a lot. I would always insist on doing it!”

Think hard about the right tempo and feel for each riff...

“Sometimes I naturally play behind the beat, like on the track Outshined. I definitely like playing that way. Matt [Cameron] was and is such a great drummer – he knew exactly how to direct and accent the groove towards my playing style. I always liked dragging the beat. It sounded a bit heavier when being on the beat could be too mechanical and stiff to my ears.

“Producers like it when you’re on the beat – they like to encourage that because it makes them look good, like they know what they’re doing. They also don’t like noise, because that’s how they represent their skills as an engineer. Unfortunately, I like all those noises [laughs]. I like disassembling the things they want to assemble. Noise and playing behind the beat are both things we would do and I will probably continue to do.”

Use extra gain only when you need it...

“Initially I didn’t use any overdrive or distortion pedals in the band, back when I was the sole guitarist. I only started when we had began using two guitars. If Chris was playing, I’d use the gain or boost just for solo sections or other colours I would add.

“When it was just bass and drums behind me, I didn’t need that. I’d just start soloing and there would be nothing else framing me or constraining me. When there’s another guitar in there, if it’s a linear note it’s less constraining. If it’s a chord, it will limit the frame in which I play – the sounds start competing so to cut through I’d add the gain.

I tried a bass distortion that was designed by Paul Barker from Ministry... They had the coolest screaming sound but I just kept blowing them

“I didn’t try out lots of pedals or anything. I knew what I wanted to change over the years but when I found what I needed, I’d often stick with that. On more recent tours it’s been the MXR CAE Boost/Overdrive. Back in the day, it was an Ibanez Tube Screamer. And the stereo chorus was Ibanez, too, the lavender-coloured one [CS9]. So yeah, it was purple and green for me!

“I also tried a bass distortion that was designed by Paul Barker from Ministry: he gave me a couple of these pedals I ended up using for my guitar. They had the coolest screaming sound but I just kept blowing them. They’d last for two shows and then die so I’d have to get another one.

“So, in the end, I started sticking to mainly boosts. I like the tone of the guitar and my fingers. I still wanted gain and to sound heavy, but I didn’t want to lose the personality... Or lack of personality, may I add, in my sound.”

Think long and hard about what each pedal does to your tone...

“When you have a distortion or fuzz pedal it changes the character of your guitar, which is why I prefer not to use them. Some bands – like Mudhoney, for example – love fuzz pedals. I find them limiting; they compress and limit things. You end up taking a lot of dynamics out, and a lot of our riffs were very dynamic-oriented.

“That was our interpretation and mood for when playing live. The expression and expressiveness was important to how we played the song and interpreted it. That might have swung from day to day. I like those dynamics – going from loud to soft, total aggression to something more fluid.

“Distortion and fuzz pedals kinda ruined that – they squished everything into a box and killed the dynamics. It also created a tone that overshot what you get out of your fingers and guitar. Eventually I found I had more range without fuzz. If you get 10 players using the same fuzzbox with the same settings, it’s going to be hard to distinguish who is who.

“Unlike synthesizers, which totally kill the element of attack and dynamics to the point of making a two year-old and concert pianist sound the same, the guitar is a real musical instrument that allows for own interpretation and expressiveness. Which is why I avoid fuzz boxes. I don’t need them to create a tone or sound. I basically need more volume and a bit more gain at times.”

Don’t automatically dismiss digital gear...

“Before Black Hole Sun, I was mainly using chorus as my modulation. After Superunknown came out, I swapped in a Rotovibe to try and simulate the Leslie cabinet heard on the recording. But actually, over the last 10 years or so, I’ve been using a digital approximation instead of an actual Rotovibe.

“I wish I could remember which one it is – my guitar tech just said, ‘Try this - go between setting A for fast and setting B for slow!’ And I was like, ‘All right, this works!’ So for Black Hole Sun, I’d use a slow setting for the choruses and the faster one for the verses and was very happy with it.”

Try using about your wah more like an envelope filter or EQ shift...

“I used my Cry Baby for Rusty Cage to help change the colour and timbre of the song. I guess the opening part has a bit of an Eastern feel, which is the kind of sound I had picked up from The Beatles and Led Zeppelin. Interestingly, it was a sound we all liked – Chris loved The Beatles too.

“Live on stage, sometimes I might have gotten bored and I might have moved my wah more. But generally I like keeping it up and open, and then leaving it there. Sometimes I might slowly move it as the song flows, just to get a 360 effect. It’s my flat impression of a Leslie, I guess [laughs]!”

Write songs that celebrate your weirdness...

“If you listen to Badmotorfinger, you might notice there are so many distinct feels across the record – different interpretations of the heavy, dark and psychedelic things we liked in music. I really like Room A Thousand Years Wide because it’s solid, heavy, repetitive and insistent.

“I like the psychedelic components of Searching With My Good Eye Closed. I’m really drawn to that. And out of the singles, I liked Jesus Christ Pose the most because of its manic-ness. It sounds like a race car or train that’s gone out of control or off the rails... It’s just trying to hang onto itself. I like that side of it.

“That song has wild elements but at the same time it’s very precise. The drum parts are challenging and there’s a very fast, rhythmic demand on the guitar, and yet it sounds like it’s spinning out of control.”

Pay close attention to your song arrangements...

“Rusty Cage is probably one of the coolest arrangements we’ve ever done. I’m so proud of Chris for writing that one. That is the most risky and courageous arrangement. The song doesn’t repeat in a traditional arrangement. Chris had this lean towards radio-friendly writing.

“He’d write songs that pushed the envelope. They were uneasy, they weren’t formulaic, but they would address an arrangement that might be good for radio. Rusty Cage is not that! It goes from one place to another hooky guitar riff that isn’t established in the verse or the chorus... It’s brilliant. I love how it switches groove.”

Amit has been writing for titles like Total Guitar, MusicRadar and Guitar World for over a decade and counts Richie Kotzen, Guthrie Govan and Jeff Beck among his primary influences as a guitar player. He's worked for magazines like Kerrang!, Metal Hammer, Classic Rock, Prog, Record Collector, Planet Rock, Rhythm and Bass Player, as well as newspapers like Metro and The Independent, interviewing everyone from Ozzy Osbourne and Lemmy to Slash and Jimmy Page, and once even traded solos with a member of Slayer on a track released internationally. As a session guitarist, he's played alongside members of Judas Priest and Uriah Heep in London ensemble Metalworks, as well as handled lead guitars for legends like Glen Matlock (Sex Pistols, The Faces) and Stu Hamm (Steve Vai, Joe Satriani, G3).

“I suppose I felt that I deserved it for the amount of seriousness that I’d put into it. My head was huge!” “Clapton is God” graffiti made him a guitar legend when he was barely 20 – he says he was far from uncomfortable with the adulation at the time

“I was in a frenzy about it being trapped and burnt up. I knew I'd never be able to replace it”: After being pulled from the wreckage of a car crash, John Sykes ran back to his burning vehicle to save his beloved '76 Les Paul