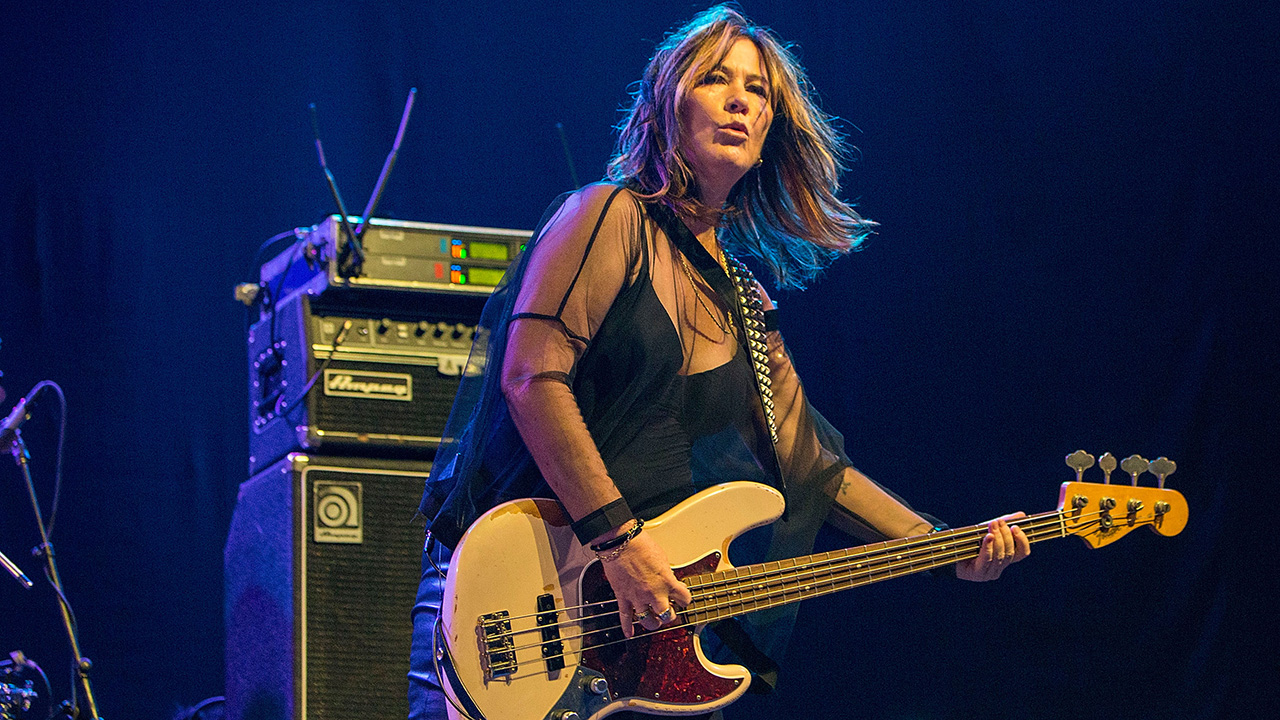

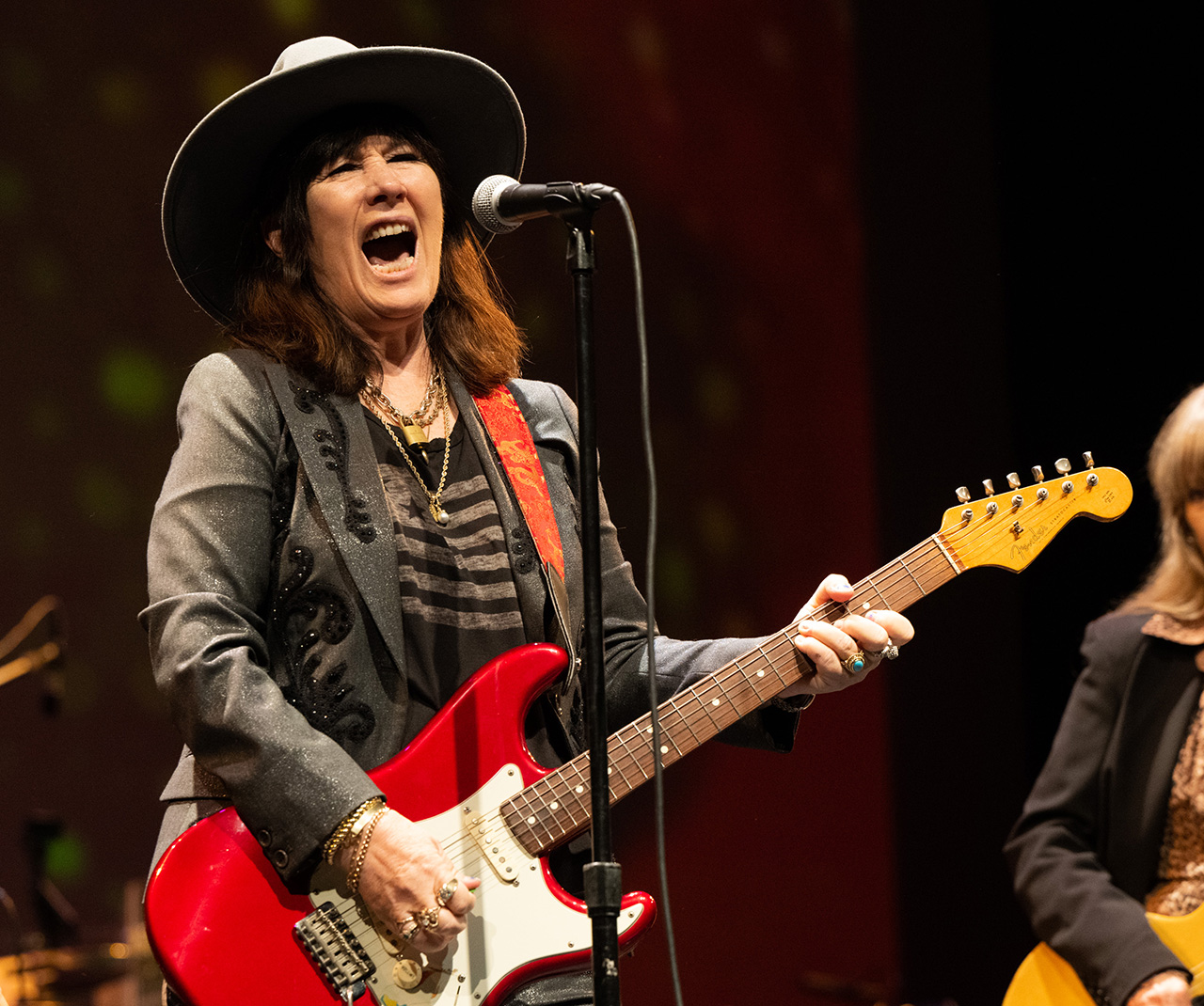

“The Go-Go’s asked if I could play bass. ‘Sure,’ I said. I had never been the bass player in a band, but I figured how hard could it be?” Kathy Valentine switched away from guitar for The Go-Go’s – until her solo skills were called upon again

The Hall of Famer on not being allowed to contribute as much as she wanted, why the band may not return, and working with Ace Frehley and Gilby Clark

In 1980 Kathy Valentine was a 21-year-old punk guitarist from Austin, Texas, who’d never have guessed she’d wind up joining LA power-poppers the Go-Go’s. But when she got together with Belinda Carlisle, Jane Wiedlin, Charlotte Caffey and Gina Schock, Valentine changed her game and switched to bass.

Their first two albums, Beauty and the Beat (1981) and Vacation (1982), were massive hits with the assistance of singles We Got the Beat, Our Lips Are Sealed and Vacation. Even before then, though, Valentine knew the band was onto something.

“Making my way through the demo tape, one thing became clear through the distortion of the cassette player: the Go-Go’s had some really good songs,” she says. “Each tune had a distinct personality and sound, and all of them were powered by great drumming and melodies.

“They blended punk, pop, surf and rock like no one else. For the rest of the day and through the night, I played those 19 songs. The next day, I did the same. I had never sustained such an undiluted, deep focus.”

As part of the zeitgeist in the early ‘80s, providing a sugary-sweet alternative to some of LA’s grittier groups, they were welcomed to the scene. “The Go-Go’s came out of the LA punk scene,” she says. “And the punk scene absolutely embraced women. Newcomer amateurs, gays, non-whites – without punk rock, there’s a massive wealth of music and talent the world would have never known.”

The band’s downfall came as fast as their success: a year after their third album, 1984’s Talk Show – which featured Valentine on bass and guitar – they dissolved. She describes the following years as “a bit lost, musically,” adding: “The Go-Go’s had kind of taken over my musical identity. I was so into being a Go-Go that once it was over, I wasn’t sure who I was anymore.”

She eventually figured it out, forming The Delphines and The BlueBonnets, before the Go-Go’s reformed in ’99. Two years later they released God Bless the Go-Go’s, which featured the Valentine-penned The Whole World Lost Its Head – their biggest UK hit.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

That album was their last, but tours followed, as did their 2022 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. As of 2024, all is quiet; and that’s not about to change. “The band is individually in very different places,” UK-based Valentine reports.

Suzi Quatro inspired you early on. How did she impact you?

“I saw Suzi [UK chart show] on Top of the Pops while visiting family in the UK in 1973. I was 14. All my favorite bands were men, and even though I’d been playing guitar it never occurred to me I could be in a band like the guys were, until I saw Suzi.

“The ground I walked on was the Stones, Hendrix, the Faces, the Who and the Beatles. Bowie, T Rex, Deep Purple, Cream, ZZ Top and Led Zeppelin added layers to the terrain I knew. Suzi Quatro split that ground wide open – she was an earthquake.

“I knew women existed in music. They sang in bands, they played acoustic guitars or sat at pianos. Years later I would learn that women had even played electric guitars in rock’n’roll, but I’d never seen or heard of any of those women. Seeing Suzi Quatro answered all the questions. ‘Where do I go? What do I do? who am I?’ Every question had an answer.”

What was your local music scene like growing up in Austin, Texas?

“Austin was a fantastic place to become a musician. I saw John Lee Hooker, Muddy, Freddie King, BB King, Albert King, Ray Charles and Little Richard as a young teenager. It was incredibly diverse; you might see Willie Nelson or Ray Wylie Hubbard or Jerry Jeff Walker one night, Maceo Parker or Bobby Blue Bland the next, the Kinks or the Ramones the next night.

“The Fabulous Thunderbirds, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and Doug Sahm were my favorite bands who played weekly gigs.”

You played with your band the Violators at Austin’s first punk club, Raul’s. What was that like?

“I had a Sunn Concert Lead cabinet and head. I played my friend's Rickenbacker or my Strat. We started Raul’s, which had been a Tejano club before booking us. We did mainly covers – Iggy Pop, Sex Pistols, a speedy punky version of [the Rolling Stones’] Let’s Spend the Night Together and a Mott the Hoople song. There were just a handful of originals. The audience hadn’t seen cute girls playing guitars before and didn’t know what to think.”

Then you moved out to LA and formed the Textones.

“The LA music scene had it all going on. Great bands of every genre played: smart, artsy, tongue-in-cheek punk bands, hardcore punk bands, power pop, new wave, rootsy pre-Americana bands and rockabilly bands. Every band had its own character, its own story.

“Anyone paying attention could figure out the big lesson: good music can find an audience. I couldn't wait to figure out where our band would fit in the LA scene.”

One of my friends loaned me a bass… I played a little like it was a guitar

What led to you joining the Go-Go's and switching to bass?

“I met Charlotte Caffey at the Whisky on December 25, 1980, at an X show. I’d seen the Go-Go’s recently; they were happening. We had shared a bill at the Whisky once – Lydia Lunch, the Go-Gos and the Textones. Girls who played in bands took notice of each other, a silent affirmation of sorority.

“She asked if I could play bass. ‘Sure,’ I said. I had never been the bass player in a band, but I figured with five years of guitar playing under my belt, how hard could it be? Charlotte said they had a four-night gig, two shows a night, starting New Year's Eve – a week later – and their bassist couldn’t play. ’I can do it,’ I said. The next morning I woke up early and called Charlotte to get a cassette of the Go-Go’s.”

What was the first bass you used?

“One of my friends loaned me a bass – the perfect bass: a small-bodied Fender Mustang with a slim, scaled-down neck. I used a pick, like I would with a guitar, and played a little like it was a guitar.

“Charlotte had given me a rehearsal tape, probably recorded on a machine as primitive as the one I used. Deciphering the recording was not so easy! Before I could get a handle on what to do on the bass, I needed to work out the chord changes and learn the melodies.”

Did the way you look at bass differently than most players?

“Feel is an indefinable thing – two musicians can play the exact same notes but they’re going to do it differently. The difference in the band after I joined was my feel, the way I played.

“Having no experience on the bass didn’t matter with the Go-Go’s. What mattered was that I understood exactly what the Go-Go’s should sound like. I knew when to swing; I knew when to drive; I knew what to listen for and I had good timing.”

You played bass on the first two records, but for Talk Show, you played a lot of lead guitar. What led to that change?

“Charlotte was struggling – she had writers block and carpal tunnel and personal issues. Rather than improvised, she writes her parts and sticks with them, but she hadn’t done that on some of the new songs. But the clock was running.

“I was thrilled to be able to add to the record, and I spent a lot of time trying to come up with parts she’d also enjoy playing once we were doing shows again.

The one thing I wish more than anything is that we'd been more flexible and open to using all our talents

“The songs on the first record were written when I joined. The guitar parts were intrinsic to the songs and perfect; I wouldn’t have changed a thing. The second record could have used more of my ideas on guitar, but the dynamics of the band were sort of rigid – ‘You play bass, stay in your lane’ sort of deal.

“By the time the third rolled around, things were still rigid and weird, but something needed to be played for solos. I made sure I had something ready to go, just in case. The one thing I wish more than anything about the Go-Go’s is that we'd been more flexible and open to using all our talents.”

By the end of the Go-Go’s’ first run, did you identify more as a guitarist or bassist?

“I just identify as a musician primarily. When I’m composing and recording in my home studio, I just hear musical ideas. It’s a matter of judgment and style on how to utilize them. ‘Is this a bass part or is it a recurring hook line on guitar? Maybe it’s a backup vocal part – maybe it doesn’t belong at all.’”

Did playing bass alter your approach to guitar?

“It might have just made me think more about what the bass might be doing. On my own, I put a scratch rhythm guitar to mess about with bass lines. If the bass starts doing something cool that doesn’t go with the guitar, I mute the guitar, go with the cooler bass part and redo the guitar.”

What led you to want to move in a bluesier direction in the ‘90s with the Bluebonnets and The Delphines?

“I had an epiphany one day – I remembered that I’d grown up in Austin, Texas and that I’d been a musician and rock’n’roll gal since day one. I thought, ‘Maybe I should go back to my roots.’ So many cool bands I loved came out of blues and roots music. I thought, ‘Start from there and see. Today, learn some blues; tomorrow, be the Yardbirds.’

“As it turns out, all the other stuff I loved along the way found its place in my musicality too. I write with influences from pop to punk to blues to country to soul and funk. I might even toss a jazz chord in here and there.”

After reuniting, you wrote the Go-Go’s’ highest-charting UK single, The Whole World Lost Its Head. Did you know you had a winner out of the gate?

“All I knew was that I had the music and the melody, and both had stuck with me for years – usually a good sign that you’ve come up with something catchy. I pulled it out in a writing session with Jane, and we had a blast writing the lyrics. The words got a bit dated, so we’d often put it into the set with updated lyrics, which is fun.”

What was it like working with Gilby Clarke and Ace Frehley on your solo album, Light Years?

We were all on the same page in our early 20s. It’s inevitable that people will evolve

“Gilby is a friend from my early days in LA, and he’s just a sweetheart. I adore him and his family. It felt safe to work with him – mutual respect and genuine friendship. Ace was gentle and kind. I met him at a birthday party of mine; he offered to play on my solo record and I thought, ‘Sure… He’ll never show up.’ But he did, and he was amazing.

“We recorded at Gilby’s studio. He came in and noodled some solo takes on Bad Choice. After a few, Gilby and I looked at each other slack-jawed and said, ‘That's it.’ He wanted to do more but I said, ‘No, this is the one. Thank you!’”

Considering the success of God Bless the Go-Go’s, why hasn’t the band put together another record?

“Writing is a bit of a chore now, as it’s very hard to agree on something we all like. We were all on the same page in our early 20s. It’s inevitable that people will evolve and change. One thing we still agree on is how much we like most of our back catalogue – it has stood the test of time.”

- Keep up with Valentine and her work with The Bluebonnets.

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.

“There’d been three-minute solos, which were just ridiculous – and knackering to play live!” Stoner-doom merchants Sergeant Thunderhoof may have toned down the self-indulgence, but their 10-minute epics still get medieval on your eardrums

“There’s a slight latency in there. You can’t be super-accurate”: Yngwie Malmsteen names the guitar picks that don’t work for shred

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)