“Hendrix came in at two o’clock in the morning. I can still remember the audience – Rod Stewart, The Beatles, the Small Faces – all of them were silent when Jimi was done”: Junior Marvin on joining Bob Marley – and the night Hendrix shook his hand

Marvin had been offered a 10 year contract from Stevie Wonder on the day he joined Bob Marley and the Wailers. But he never looked back

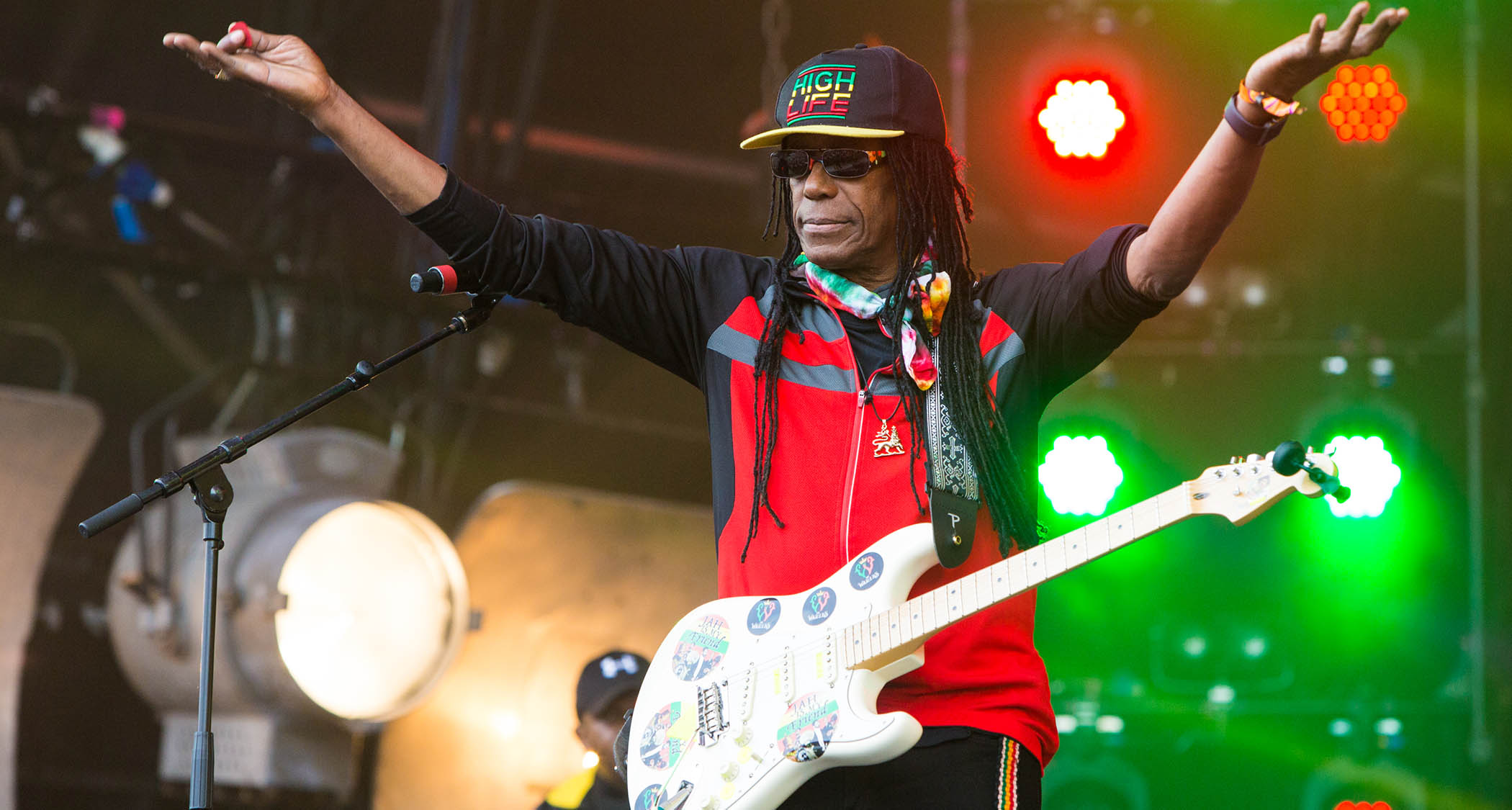

Junior Marvin might not have been with Bob Marley at the beginning of his legendary career, but he was there for its height and the reggae icon’s untimely end. But before that, Marvin – born Donald Hanson Marvin Kerr Richards Jr – was a dyed-in-the-wool Beatles and Jimi Hendrix fan, who had renounced an early education in classical piano and formed an obsession with British rock. This led him into a hearty session career before forming his band, Hanson.

Hanson didn’t stick, but Marvin’s reputation as a capable six-stringer did, leading to an unexpected call from Stevie Wonder on Valentine’s Day 1977. This turned out to be the very same day he was set to match wits in person with Bob Marley, leading to his initiation into The Wailers and contributing to some of Marley’s most well-known records: Exodus, Kaya and Survival in the late 70s, and early 80s records Uprising and Confrontation, the last of which was released after Marley’s death in 1981.

Marvin has accomplished a lot in his career, but it’s his time alongside Marley that means the most, even though some of his former bandmates – and Marley cohorts – seem to throw shade the fallen vocalist’s way.

“The funny thing is, if you ask me about this stuff, the answers just come out as they do because it’s the truth,” Marvin tells Guitarist. As for what Bob Marley meant to him, Marvin is emphatic, saying:

“Bob was a workaholic to the man, but it was good for all of us. We got into the same mode and never had to think about it. We just did it. And when we were done, we slept well because we’d learned so much. We learned things we never thought we would to where it was like out of body, you know?

“That was one of the gifts Bob gave me,” he reflects. “I learned from Bob that it’s always better to give than to receive. When you give someone even a small gift, the feeling is better than anything. I carry that with me in everything I do, and I have Bob to thank for it.”

Going back to the beginning, what gravitated you toward music?

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Most of my family played the keyboard, and my great-aunt graduated from the University of the West Indies in Kingston, Jamaica, and was a piano professor. Her job was also to teach all her siblings, as her father couldn’t afford to send more than one kid to college. So my father was her protégé and he imparted classical and jazz piano to me.

My father tried to teach me piano and, although he was great, he wasn’t a good teacher and I didn’t like it. He started me off when I was only a few years old, and I’d get hit by one of those old round canes whenever I’d hit a wrong note!

“My father tried to teach me piano and, although he was great, he wasn’t a good teacher and I didn’t like it. He started me off when I was only a few years old, and I’d get hit by one of those old round canes whenever I’d hit a wrong note! I’d hear that cane coming, and I knew the pain was about to hit me, so I didn’t like the piano much.

“As for the guitar, I ended up in England with my mother after my parents were forced to split up, and I wanted to play soccer and do gymnastics – anything but piano. I’d sit for hours with my friends and play in the street and, eventually, I saw Elvis and The Beatles on television, which got me into guitar. Finally, my family said, ‘We’re not going to try to teach you piano any more.’ I said, ‘Okay, thank you!’”

Elvis and The Beatles aside, who were your greatest influences?

“I was already familiar with jazz, R&B and all the West Indian stuff. After that, I got into Hank Marvin from The Shadows, Duane Eddy, Chuck Berry and T-Bone Walker, who I worked with when I was young. Then I got more and more into rock.

“I loved Little Richard, who was a significant influence on The Beatles but with a different vibe. I did love The Beatles and how they told stories with songs like Eleanor Rigby and All You Need Is Love. I also loved The Animals, but then Jimi Hendrix came to town, and I was like, ‘Wow… where did this come from?’

“When Hendrix came to my area in England, I remember he’d play clubs and speakeasies at midnight, and all the musicians would hang out there. I was underage, but my manager at the time would get me in for free to watch, though I couldn’t drink any alcohol.

“One night, I was there and Jimi came in to jam at around two o’clock in the morning. I can still remember the audience being filled with people like Rod Stewart, The Beatles, members of the Small Faces – all of them were silent when Jimi was done.”

Was seeing Hendrix in that setting a defining moment?

“Yes. I said to myself, ‘Now there’s a guitar player. I want to play guitar like that.’ I went right up after he was done, met him and shook his hand. But Jimi was so shy and wouldn’t even look at me to say hello.

“It was crazy: here was this guy who was just up on stage playing guitar behind his neck and barely even talking to me. He was like two different people. But I got to shake Jimi Hendrix’s hand; I was very proud of that.”

Eventually, you became a sought-after session guitar player. What allowed you such versatility?

“I liked the idea of playing a little bit of everything. I have a very varied background and like a lot of music, so it made sense. Music is like another language to me, a universal language, so the ability to play a lot of different styles was fun, and I took to that very quickly.”

Is it true that you auditioned for Jeff Beck’s band?

“Yes, I was with Cozy Powell on drums, Max Middleton on piano, Clive Chaman on bass, and Bobby Tench on vocals. When I went out for the audition, I took those guys because they were my friends. In the end, Jeff pulled me aside and said, ‘I’ll take your mates, but I can’t take you.’ I said, ‘Why not?’ He said, ‘You need to form your own band.’

“I was kind of mad because I took those guys there to support me, not support him! But it turned out to be a blessing in disguise. I formed a band called White Rabbit with a lady named Linda Lewis, a famous British vocalist. We took the name from the Jefferson Airplane song of the same name, did some club dates and ended up breaking up.”

Is that when you formed Hanson?

“Yes. It was a rock band, also when I changed my name. I was born Donald Hanson Marvin Kerr Richards Jr, but I was going by Junior Hanson by then. I wanted my initials to be JH like Jimi Hendrix, but eventually, as we know, I began to go by Junior Marvin. I wanted to play rock, though, not reggae. I was proud that I could sign with Manticore Records and make two albums, Now Hear This and Magic Dragon.”

When I picked up the phone, I said, ‘Are you sure you’re Stevie Wonder?’ because I had difficulty believing he’d be calling. He said, ‘I’ve heard your albums and I like your feel... I’d like you to join my band, but if you do, I need you to sign a 10-year contract’

Fast forward a few years and you were faced with either joining Stevie Wonder or Bob Marley…

“I had done some session work with Steve Winwood, and producer Chris Blackwell had heard it, liked it and thought it was Steve playing. He said to Steve, ‘Hey, you changed your playing style; I really like it.’

“Steve said, ‘Oh, that’s not me. It’s this guy named Junior Marvin, who is this little guy from Jamaica.’ So Chris Blackwell came looking for me, we talked and then he said, ‘I want you to meet somebody…’ He wouldn’t tell me who it was he wanted me to meet, but I agreed.

“So it’s Valentine’s Day in 1977 and I’m in England again as I was taking time off from playing. Just before Chris picks me up, I get a call from Stevie Wonder at my house. Stevie’s guitarist couldn’t do the tour, so Stevie needed a guitarist. Stevie had heard I was a good player and might be interested, which I would have been as I’m a big Stevie Wonder fan.”

“But when I picked up the phone, I said, ‘Are you sure you’re Stevie Wonder?’ because I had difficulty believing he’d be calling. He said, ‘I’ve heard your albums and I like your feel.’ I said, ‘Okay…’ and then he said, ‘I’d like you to join my band, but if you do, I need you to sign a 10-year contract.’

“I thought, ‘Wow. If I do that, I’ll become a household name,’ which gave me goosebumps; it was crazy. But as I was thinking about it, Chris Blackwell knocked on my door to pick me up to meet ‘somebody’. I told Stevie, ‘Can I think about it? 10 years is a long time. I’ll call you back in a couple of hours.’ Stevie said, ‘Okay, no problem,’ and off I went in Chris Blackwell’s Rolls-Royce with my guitar.”

Is it safe to assume that ‘somebody’ was Bob Marley?

“Yes. Chris takes me to this fashionable area and this big Edwardian house. We go in and I see from behind this little guy with dreadlocks who had this aura about him. I’d heard about auras, but I’d never seen one before – this guy had that. He turns around and it’s Bob Marley. He walked right up to me, and I’m like, ‘Holy shit,’ and he slaps me five and says, ‘Welcome to The Wailers, man.’

Stevie said, ‘Take the job with Bob and if in a year you’re unhappy, leave anytime and you’ll have a job with me’

“I said, ‘Don’t you want me to play some guitar?’ He said, ‘Yeah, you can, but we want you to join, man. We like the way you play.’ I pinched myself, like, ‘Wait a minute: something is so weird here. I’m getting calls from Stevie Wonder and being asked to join Bob Marley?’ Anyway, I jammed with Bob on a couple of songs for about an hour, stuff like Exodus, Waiting In Vain, and then I remembered, ‘Shit. I’ve got to call Stevie Wonder.’

“Chris was already talking about recording sessions and starting rehearsals. I said, ‘Man, these guys don’t even know me…’ Chris stopped me, saying, ‘Yeah, we do. We’ve been studying you for over a year. You’re who we want.’ They knew what type of person I was and that I was balanced. So, I said, ‘I want to make the right decision. Can I get right back to you?’ He said yes and took me back home.”

History reveals that you joined Bob…

“Before I left, Bob handed me five records, saying, ‘Study these overnight and be here tomorrow.’ I grabbed them, said, ‘I gotta go,’ got home, called Stevie and said, ‘I’m so sorry, but I’ve just been offered a job with Bob Marley.’ He said, ‘Oh, I met Bob a month ago in Jamaica. He was great!’ They had jammed and people loved it, so he wasn’t upset; he liked Bob.

“Stevie said, ‘Take the job with Bob and if in a year you’re unhappy, leave anytime and you’ll have a job with me.’ It was crazy as there were a lot of guitar players out there, but for some reason, both Stevie and Bob wanted me. Anyway, as they say, the rest is history.”

What did you bring to Bob’s band that other players like Peter Tosh and Al Anderson didn’t?

“I was very into Hendrix and loved rock, so there was that. Peter was Jamaican and Al was a guy from America, so their sensibilities were different. They couldn’t escape those influences, you know? That’s not a bad thing – it was just different. Bob also had a guy called Donald Kinsey, who was very blues-based and a protégé of Albert King, so I was very different from those guys.

“I listened to a lot of different music, so when I hear a new song, I have a massive library or arsenal to draw up. My father always told me, ‘Don’t overplay; less is more,’ so I’m a team player. I never wanted to show off or fill space with all kinds of sounds and technical stuff. My goal was to enhance the song and add icing on the cake. That’s what the other guitarists in Bob’s band maybe didn’t have.”

Can you remember the intent behind your first record with Bob, Exodus?

“Exodus was like a miracle for the movement of people it was speaking to. In other words, the album is like the movement of God’s people. The lyrics are about people fighting and then they see the light and everything is all right.

“When we made that album, we understood the idea that life is a gift for everyone on Earth and that the idea of putting people in jail or making slaves out of them ruins that gift. That music is about freedom, redemption, fighting for resources, and feeding the world, rather than going to war.”

I resonated with Bob because we had similar feelings about life and how people should be treated. We prayed for everyone to be educated, fed and have roofs over their heads

It sounds as if your connection with Bob ran far deeper than only guitar.

“It did. I resonated with Bob because we had similar feelings about life and how people should be treated. We prayed for everyone to be educated, fed and have roofs over their heads. These are basic things in life; no-one should be starving or hungry, so we and our music were all about that.

“The Earth belongs to all of us, as did that music. Anyone can make music, but to sing about suffering and make that music in a language that we spoke together is what finding common ground and learning are all about. You don’t just listen; you feel it.”

What gear did you lean on most with Bob?

“The secret weapon was some of the fuzz boxes that Hendrix used in the late 60s – and even Keith Richards on songs like (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction. Those pedals and inventions were essential and they shaped the sound. Other than that, I used Les Pauls, Strats and all sorts of things depending on what the song called for.

Before Bob died, he said, ‘Play the music. But if you can’t meet the standard we’ve set – don’t f***ing play it at all’

“Often, it was more about the feeling than the gear. But we didn’t always have much money for that stuff anyway, which was fine because Bob was a rebel and wasn’t really into money. He couldn’t be influenced in that way.”

You’ve done an outstanding job carrying on his legacy with The Legendary Wailers.

“Before Bob died, he said, ‘Play the music. But if you can’t meet the standard we’ve set – don’t fucking play it at all.’ He didn’t want us to play it the same way but to make it better, or at least keep trying to. Bob was a perfectionist and a workaholic. So that’s the standard I hold myself to.”

With all the folklore surrounding Bob, the picture of who he really was becomes a bit blurry. Who, from your perspective, was Bob Marley?

“Who Bob really was? Bob never cared about money. He helped a lot of people go to college, start businesses and even helped gang guys who tried to intimidate him with a gun. These were guys who played around with guns, would ask for money and committed serious crimes. But Bob said, ‘Okay, here’s $20,000, go start a business. Don’t kill anyone else. Go start a business and be a good person.’

Bob was a gift, as was working with him and the music he left behind

“That’s who Bob really was. It meant a lot to him to save someone, rather than turn them away and let them kill more people. He grew up with many guys like that and, in the end, they all looked up to him because he was successful. I don’t know what else I can say besides that he was spiritual and believed in the Rastafari father of creation. Bob was a gift, as was working with him and the music he left behind. That’s how I remember him.”

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.

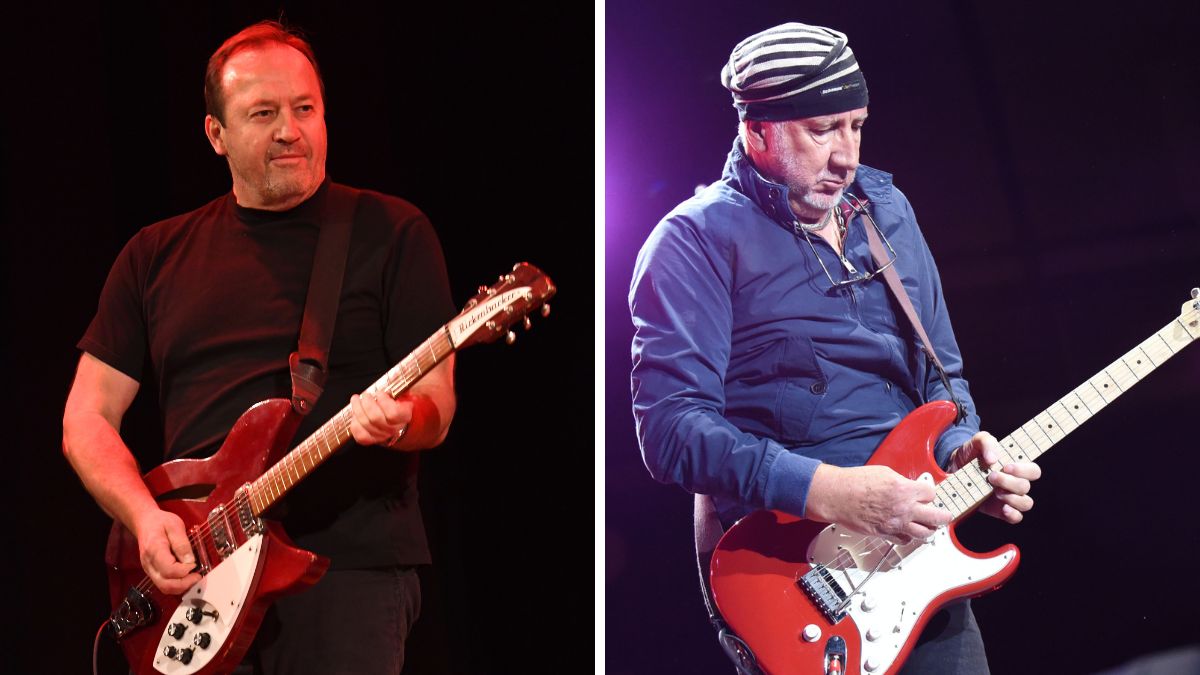

“My guitar tech ran in and said, ‘Hey, you want to meet Pete?’ I was too scared”: The Smithereens’ love affair with The Who goes way back – yet when guitarist Jim Babjak got the chance to meet Pete Townshend, he turned it down

“Every tour was the best I could have done. It was only after that I would listen to more Grateful Dead and realize I hadn’t come close”: John Mayer and Bob Weir reflect on 10 years of Dead & Company – and why the Sphere forced them to reassess everything

![John Mayer and Bob Weir [left] of Dead & Company photographed against a grey background. Mayer wears a blue overshirt and has his signature Silver Sky on his shoulder. Weir wears grey and a bolo tie.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/C6niSAybzVCHoYcpJ8ZZgE.jpg)

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)