Joshua Crumbly talks playing with Kamasi Washington and Leon Bridges, and gigging jazz standards at 10 years old

The broad-horizoned bassist on making his new solo bass album, ForEver, and how advice from Marcus Miller began a lifelong obsession with the instrument

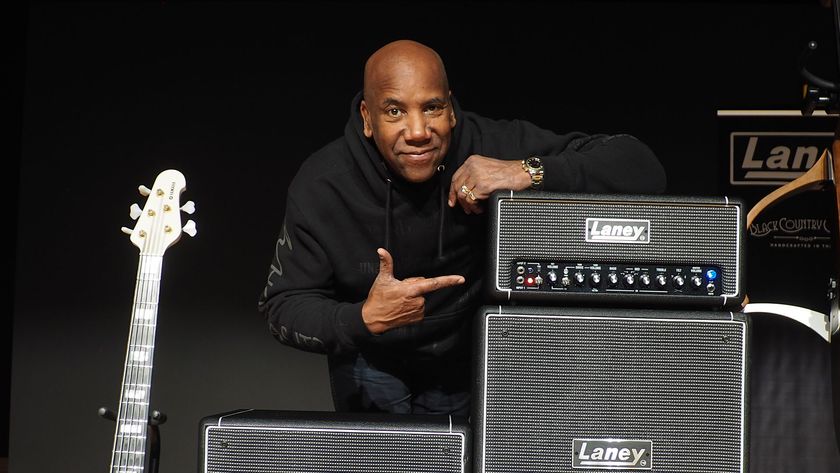

Bassist, producer, and songwriter Joshua Crumbly has just released what might be the bass album of the year, ForEver – an atmospheric, unpredictable collection of songs that cover a whole range of territory.

This will come as little surprise to anyone familiar with his career as a recording and touring bassist with artists such as Kamasi Washington, Leon Bridges, and Terence Blanchard. Crumbly’s debut album Rise was released in 2020, and together with the new release, adds up to a body of work that has been a long time in the making.

Congratulations on ForEver, Joshua. Tell us about the album.

“I’ll never forget the day I decided to do it. I had actually just finished my first record, and I felt really proud of myself – like, ‘Okay, my work is done for a while.’ I was in Florida on tour, and this number that I didn’t have in my phone called me.

“I picked up, and it was the bassist Shahzad Ismaily. He said, ‘Hey, this is Shahzad – you need to record a solo bass album.’ And I’m like, ‘Okay!’ He graciously opened up his studio, Figure Eight in Brooklyn, to get it started, and then it sat for a little while. When the pandemic happened, I had all this unexpected time to finish it.”

What were your inspirations?

“It started as a solo bass project, but then it conceptually branched out with all that was happening in the world, and all the important things that came to the forefront – like family and love and connections. I ended up playing drums and keys on some of it, and if I was hearing a friend’s voice strongly, I would call them in on a track here and there.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

How much of the music is improvised and how much of it was arranged out beforehand?

“A lot of times I’ll pick up the bass and play an introductory improvisation, which then turns into a theme. In the past, I would let those moments go and not document them. These days, I think ‘Let me put this to tape.’

“After that, the record started taking shape very naturally. I recorded a lot of the album through a Universal Audio interface into Pro Tools, Logic, or even GarageBand. I used a lot of plugins – delay, chorus, and re-amping – a bunch of crazy things.”

It sounds like there’s a bit of looping going on as well.

“That’s one of the great things about the record – there are no loops. I actually played each track, top to bottom.”

Everyone’s going to say to you, ‘Great loops, Joshua.’

“I know – it’s gonna be really annoying. I just feel like there’s a human element if you don’t loop. Even if I’m playing the same thing over and over, there’s going to be little subtle differences and imperfections that create more of an emotional experience. I want to bring the feel of me coming from a jazz background and doing it all live, and having that human essence to it.”

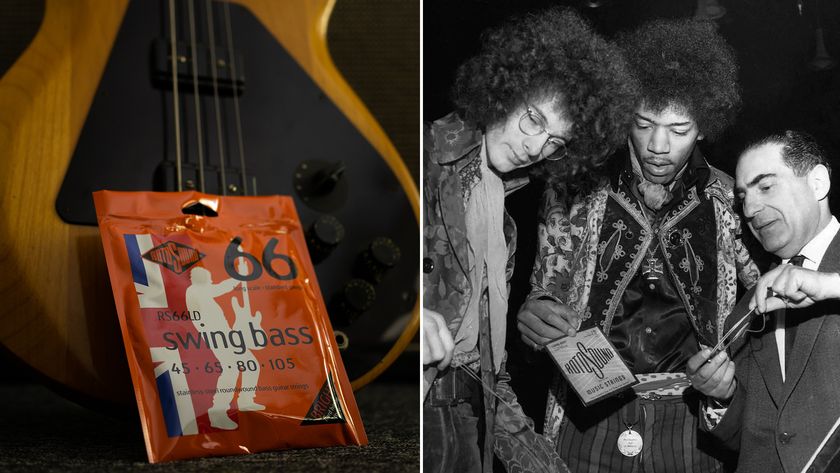

Tell us about the bass guitars.

“There’s a lot of Fender Ps on the record, and on the title track I’m using an MTD Kingston, which was my first pro-level instrument. That’s a special bass that I hadn’t played for a long time until that moment.”

How did you get into bass? I know you started at a very young age.

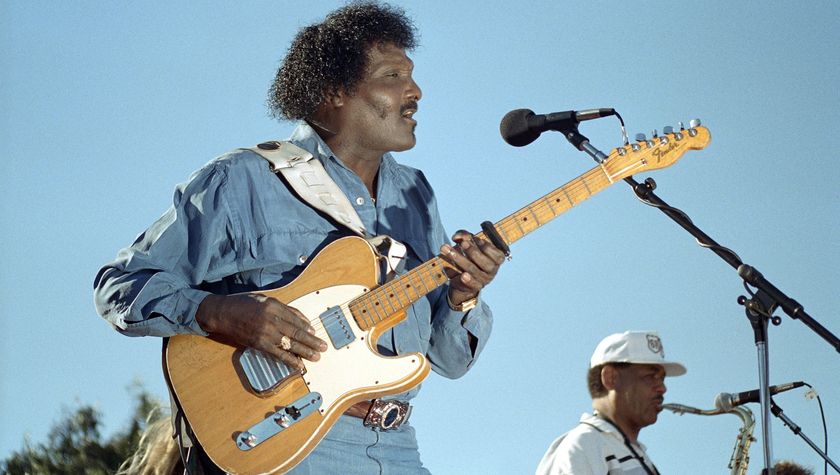

“I’m an only child. I begged my mom and dad for siblings, but that never happened because I guess I was too much of a handful, so my dad, Ronnie Crumbly, functioned like a big brother as well. He’s a saxophone player, and when I was young, he had a bunch of his own bands, and was gigging around the Los Angeles area every weekend.

“He did some touring with Solomon Burke and with a South African gospel artist named Kim Clement. He’s the man! So I would follow him to all his gigs. I would sit there with my mom and my coloring book, and for whatever reason, the electric bass always attracted my attention most out of the whole group.

“My dad always played with amazing bassists, and one of the first bassists I got to see was this guy we called Uncle Charlie – Charlie Jordan – who slapped a lot. He was heavily influenced by Louis Johnson. As a kid, I was like, ‘Oh my God, this is incredible – I want to do that, too.’”

Which other bass players were you aware of back then?

“Well, my dad ended up getting me some Marcus Miller records – I checked those out nonstop at home. After that, it became a tradition for me to go see Marcus Miller play. I’d go and see him for my birthday, when he would be playing in LA. One time my dad went up to Marcus after one of the shows, and Marcus was like, ‘Get your son a bass. You never know what’s gonna happen, but if he’s showing that much interest, go and get it.’”

Sound advice.

“Absolutely. Long story short, my dad persuaded me into playing piano first. He was like, ‘You know, every great bass player I know is proficient at piano,’ which was solid advice too, right? So I treated it as a stepping stone to get to the bass, eventually, but I ended up enjoying it.

“I played classical piano from the age of five to nine – and then at nine, I was like ‘All right, I’m ready,’ and I got an electric bass, a three-quarter size Hondo. I still have it. My second bass was the MTD Kingston, and then I went through lots and lots of Fenders.”

What was your first professional gig?

“With my dad, actually – pretty much as soon as I started playing bass at 10 years old. I told him, ‘I want to be your bass player,’ and he was like, ‘Well, you’re gonna have to learn a bunch of standards’ and he got me a Real Book. I ended up learning about 30 songs and doing a restaurant gig twice a month with my dad. Sometimes we would switch from jazz to some R&B like Earth, Wind And Fire.”

You were playing Real Book material at the age of 10?

“Yeah, although I never really thought about it. It was just happening so naturally, and I guess I had a vision, even back then. I never thought about it being out of the ordinary.”

So did you go to college?

“Yeah, I went to Juilliard, which was a bittersweet experience, because I was touring a bunch at the same time. As soon as I got there, I got a dream call to join Terence Blanchard’s quintet. I was out on the road a lot, and that created tension with the artistic director at Juilliard. But you know what, looking back on it, I’m glad I did it. I graduated on time, and I got to study with Ron Carter and learn some classical harmony. So you know what, today I’ll say it was a great experience.”

If I was an up-and-coming jazz bassist that wanted to move to New York, I would do my best to get in touch with Ron Carter, and study privately with him

Would you say that a degree in music is useful for jazz bass players?

“Actually, I’m not sure. The only reason I say that is because I was blessed to get a scholarship, a pretty sizable one, but it still cost a lot of money. If I was an up-and-coming jazz bassist that wanted to move to New York, I would do my best to get in touch with Ron Carter, and study privately with him.

“I would also encourage people to reach out to Kendall Briggs, a counterpoint teacher at Juilliard, who also teaches privately. But if money is not an issue, then yeah, I would totally recommend a degree, because you become part of a network of musicians. I still have very close friends from those days that I stay in touch with.”

Have you been a musician ever since then?

“Yes, I’ve never had a regular job. I guess I’ve technically been a professional musician since I was 10 years old. It’s funny that you ask this question, because for years, I often wondered what it would be like to have a nine-to-five job.

“In my own mind, I was finding beauty from looking at other people that have the same kind of regimen every day. During the pandemic, I thought that might be nice instead of just moving around constantly. I even thought about applying for a job at Whole Foods or Trader Joe’s.”

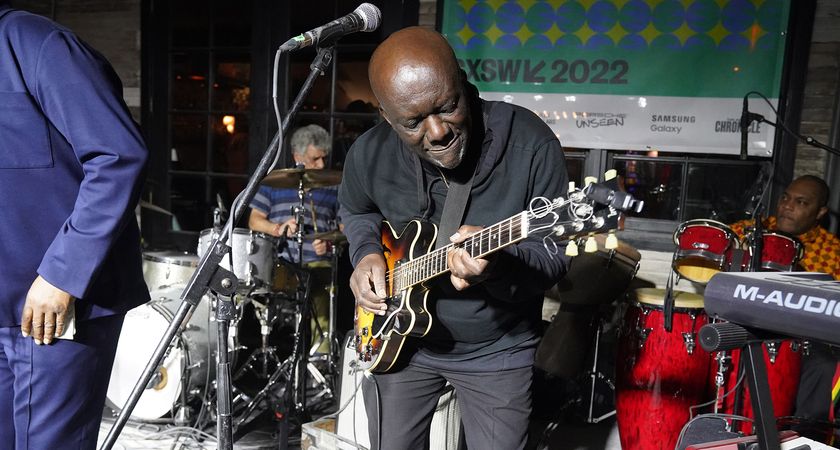

That probably wouldn’t be as much fun as playing with Kamasi Washington.

“Yeah! I did a couple years with him. That was an important experience for me, because before that I was really heavily involved in the modern jazz scene in New York. It was all very serious and structured, and played by some brilliant minds, of course – but the thing about Kamasi was that he got me back to just going balls to the wall, like I used to when I was a kid.

“Just going for it and not really thinking too much. That gig led to the band I’m in now with Leon Bridges. It’s weird how your career can be made up for things that you think are completely unrelated. That’s not the case – they all lead to the same path.”

How are you evolving as a bass player?

“That’s an interesting question... I think I’m more comfortable with space, and drawing a meaning to it in different ways – just because I’m going through different things as a person now, and I’ve been on the earth for a longer amount of time. Music gets more and more meaningful as time goes on.

“I will say there’s definitely some similarities to how I used to play. I’ve always been a very supportive musician, because from day one, I was playing with older musicians, and obviously staying in the pocket was strongly encouraged.”

What are your priorities in 2022?

“Creating a healthy environment on and off the stage is paramount, you know, and so is making everybody feel special and allowing people to shine. It’s really just about having this beautiful communal experience.”

- ForEver is out now via figureight.

Bass Player is the world’s most comprehensive, trusted and insightful bass publication for passionate bassists and active musicians of all ages. Whatever your ability, BP has the interviews, reviews and lessons that will make you a better bass player. We go behind the scenes with bass manufacturers, ask a stellar crew of bass players for their advice, and bring you insights into pretty much every style of bass playing that exists, from reggae to jazz to metal and beyond. The gear we review ranges from the affordable to the upmarket and we maximise the opportunity to evolve our playing with the best teachers on the planet.

“The six-string bass guitar was a dream – if Leo Fender could come back today I think he would approve”: 10 6-string bassists you need to know

“It’s great to tap like Les Claypool and thump like Marcus Miller, but the world of a studio bassist is different”: Having graced hits by OutKast, TLC, and Usher, LaMarquis Jefferson carved a niche in a scene long dominated by synthetic low-end

![[L-R] George Harrison, Aashish Khan and John Barham collaborate in the studio](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/VANJajEM56nLiJATg4P5Po-840-80.jpg)