“As a guitarist you can come in after the one without the house falling apart. But as a bass player, you always have to be there”: How Jonas Reingold switched from classical guitar and became Steve Hackett’s go-to bassist

From Wire and Karmakanic to the Flower Kings and Steve Hackett, the Swedish musician loves to learn, and always strives to be a better team player

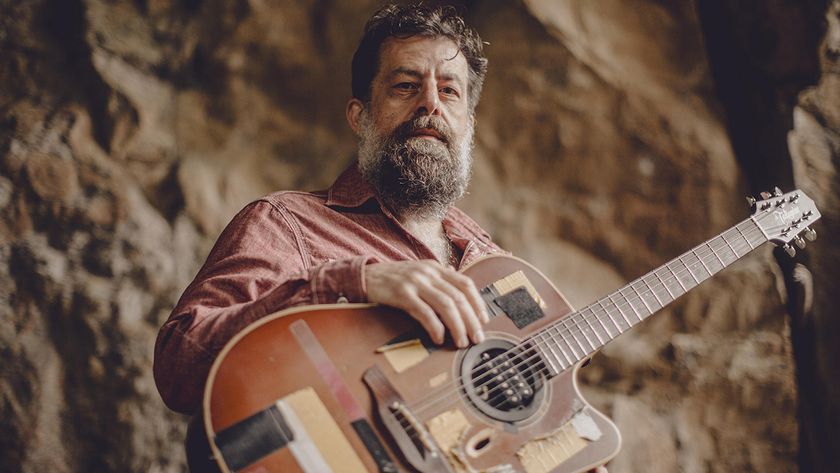

If you’re in the market for a bassist capable of tackling anything from angular post-punk to the Swedish prog rock to the virtuoso smorgasbord of Steve Hackett, you needn’t look further than Jonas Reingold.

He has a masters degree in fine arts and was a busy session player in the ‘90s before forming Karmakanic in 2002, and then joining Hackett’s band in 2019.

And he’s still open to expanding his repertoire. “I’ve become a better team player over the years,” Reingold tells Bass Player. “I’ve learned to play what’s needed, leave the ego behind, and do exactly what’s needed for any section.

“I used to play too much and justified that by calling it ‘creative overplaying.’ My ego was in the way – I wanted to be heard. Nowadays I’m much cooler, focusing on the total sound of the band. I guess I’m a better listener.”

What inspired you to pick up bass?

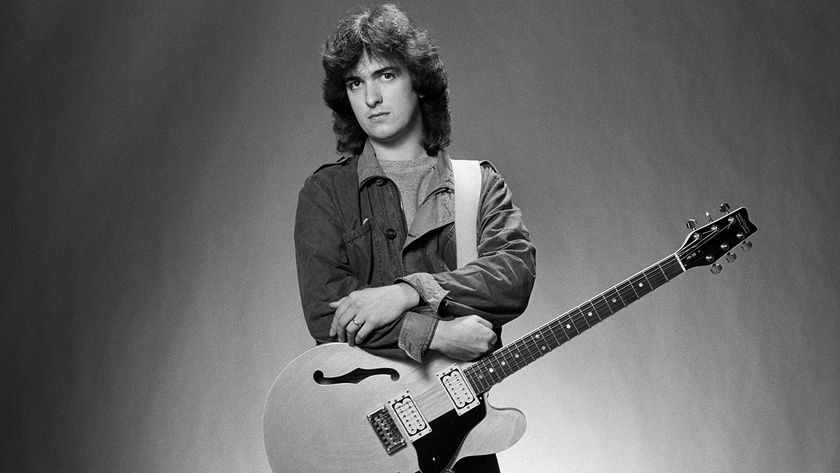

“I was a guitar player at the beginning and I was kind of serious about it. I applied to a music school after elementary school, something we in Sweden call gymnasium: two years of study at 16 to 18 years of age. It was a secondary school that prepared us for higher education – university and such. I studied classical guitar there.

“During that, I heard Jaco Pastorius for the first time, which changed my life completely. A friend of mine played Bright Size Life by Pat Metheny, and I was mesmerized by the bass tone and Jaco’s expression.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

How did you got the gig with Swedish rock outfit Wire?

“I was asked to substitute for the bass player between two semesters, so I borrowed a bass – a Gibson Grabber – from a friend and started to practice a bit. They liked what I did and asked me to be a permanent member after that summer break.”

What gear did you lean on?

“When I got the position in Wire permanently, I could only afford a cheap Ibanez bass. I can’t remember the model, though; it was stolen a few years later.

“I had a second-hand Roland Studio Bass 100 amp along with the Ibanez. I bought a Rickenbacker 4001 a few months later, which had a natural finish, but I spray-painted it in neon green… It was the ‘80s and the era of hair metal bands!”

What was the most challenging thing about tackling Wire’s music?

“The most challenging task was seeing myself as a bass player. I was 17, and it was a different mindset compared to guitar. Lock in with the kick drum; be the first on the one. As a guitarist, you can always come in after the one in a new section without the house falling apart. But as a bass player, you always have to be there.”

Was it difficult moving into session work?

“I come from a small town, and there was basically no session work to be done. That came much later in my career when I moved down south and started at the University of Music in Malmo.”

What did your session rig look like?

“In 1990 I wasn’t so seasoned. I didn’t have a special studio rig so I mostly showed up with my bass and we lined in directly to the console through a compressor that the studio provided, and it went straight to tape. No fancy stuff at all. Sometimes I used an amp from the studio that I distorted and mixed with my clean signal, mainly when I worked on harder music.”

How did you end up with The Flower Kings?

“In late 1998 the drummer, Jaime Salazar, asked if I wanted to go to Uppsala and try out for his band. I didn’t know the band then so he gave me a few CDs to listen to and four or five songs to learn.

“I liked the stuff very much, and we arranged an audition in February of 1999. I guess it went well because the next day, I got an email from Roine Stolt offering me a European tour for April.”

What did you bring to the mix?

There are far too many copycats out there – the world doesn’t need another one. Listen to your inner voice

“I brought a touch of jazz – I was heavily into jazz-fusion, but I also liked the progressive rock that I listened to as a kid: Rush, Yes, Pink Floyd. I could hear similar elements in the music of The Flower Kings, so I felt at home immediately.”

Is there something about prog rock that you identify with specifically?

“The good thing about progressive rock, with its roots in the ‘70s, is that everything is allowed somehow. Mixing in some Jaco vibes with the rock sounds of Chris Squire was no problem, and that created my sound to this day.

“Later, I also brought a few songs from my pen to the band. I felt like a real member both musically and artistically – I was a part of shaping the band’s sound.”

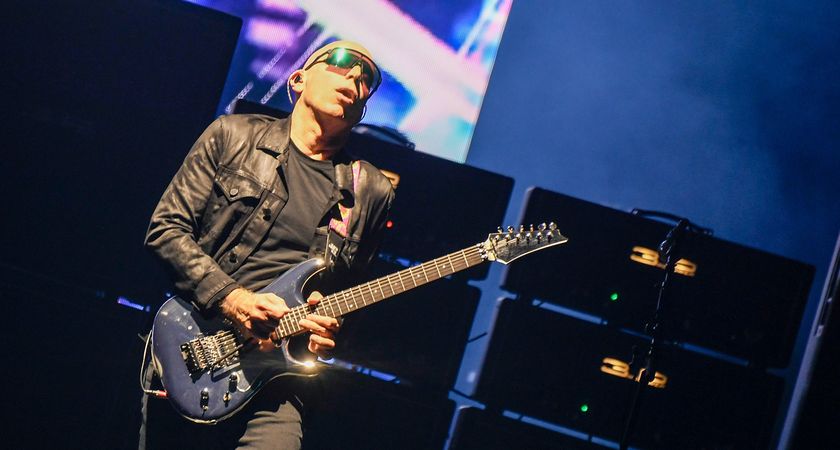

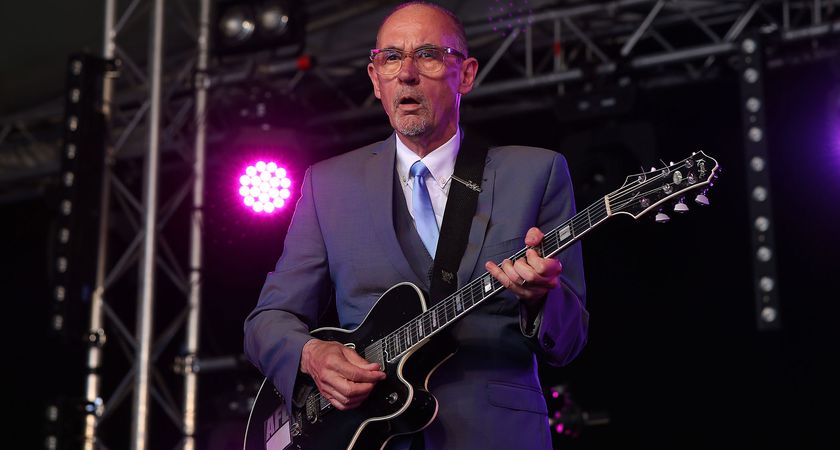

You’ve been backing up Steve Hackett for some time now. How did you get the gig?

“There wasn’t really an audition; I was friends with saxophonist Rob Townsend, and one day he said, ‘Steve doesn’t have a bass player.’ Nick Beggs had got the gig with Steven Wilson and couldn’t do Steve’s next tour. I told Rob I would like the gig, and he said, ‘Funny you say that, because I’m having a curry with Steve tonight.’

“The next day, I got an email from Steve asking me to send him some stuff with my playing. I Googled myself, found a few YouTube links and copied them into the email. A few days later, he phoned and offered me the gig.

“We had a formal lunch in London; he wanted to check me out to reassure himself that I wasn’t a complete madman! We had a handshake and he said, ‘Welcome aboard.’”

What is your bass rig like with Steve?

“I’ve been collaborating with a Swedish bass company called EBS for 25 odd years, so I chose two EBS Classic 500 heads and 4x10 ClassicLine cabinets. I have a few pedals – Tech 21 VT-Bass, OKKO FX Cocaine compressor/preamp, and an EarthQuaker Devices Sunn O))) octave distortion.

“Depending on the setlist, I also have a delay for the fretless bass. I play bass pedals with my feet, using a Roland PK-5 MIDI controller that goes into keyboardist Roger King’s rig for fat Taurus bass sounds.”

What’s the key to locking in with Steve?

“Know the songs, show up on time and smile now and then. It saves you time, and you can focus on the musical expression directly instead of going over chords and notes. If everyone does their homework, things will flow much more easily.”

And what has Steve taught you?

“The most important thing is to be yourself musically. Don’t listen to trends; do your thing, and you will find your place in the universe. There are far too many copycats out there – the world doesn’t need another one. Listen to your inner voice and act accordingly.”

I’d spend up to 10 hours a day learning new concepts and transcribing solos from great players

What would you like to accomplish next, and what's your plan to make that a reality?

“My short-term goal is to finish the next Karmakanic album. I've written all the songs for it; I have about 65 minutes of music to record. I have an eight-week US tour with Steve and I’m preparing for that, learning some new songs and preparing the little bass feature I do every night.”

How about the long term?

“I want to continue to improve. I would like to have more time for practicing as I did in my youth, when I’d spend up to 10 hours a day learning new concepts and transcribing solos from great players. That aside, I’ll continue to make the best music possible and keep evolving.”

- See JonasReingold.se for more info.

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.

“You can set up amplifiers and drums to your heart’s content”: Gene Simmons defends paid roadie scheme

“I woke up to a DM from Shirley Manson asking if I'd be interested in the gig. We had never met”: Former Smashing Pumpkins bassist Nicole Fiorentino on how she landed her role in Garbage – with no audition