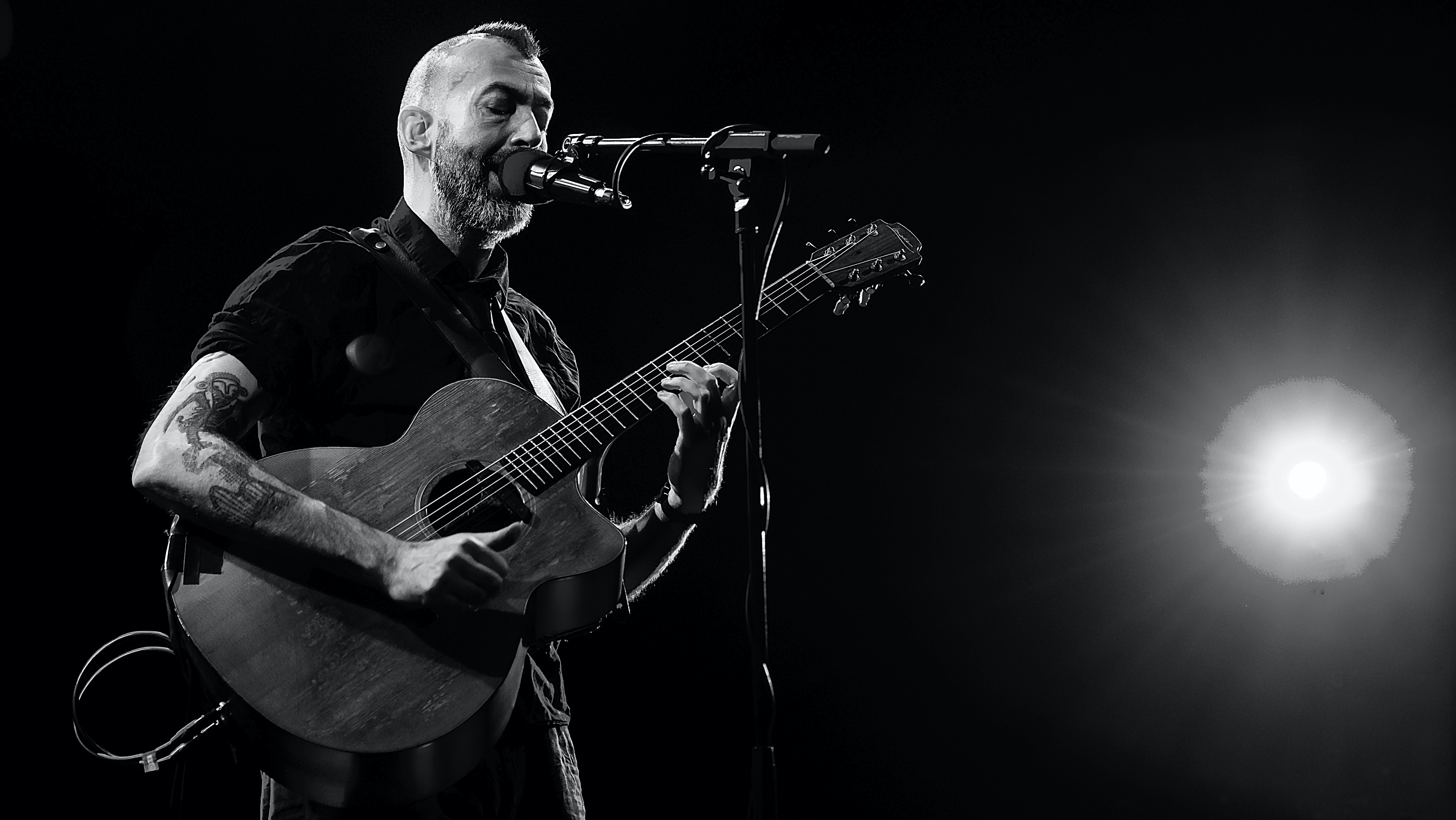

Jon Gomm: “It's inevitable that when I write a new song I'm going to have some ridiculously complex way of playing it“

The English acoustic guitar trailblazer on beauty over technique, audience expectations and his game-changing new Ibanez acoustic

Jon Gomm is one of a new breed of acoustic guitar players whose adventurism with technique has opened up new avenues for his songwriting.

This modern fingerstyle, as Gomm calls it, might be traced back to players such as Michael Hedges, but in terms of its pop-cultural significance and artistic potential, it has only just got started.

Pull back the curtain on Gomm's latest album, The Faintest Idea, and you'll find a roman candle of bravura techniques – eight-finger tapping, knuckle-popping phrasing, percussive raps on the soundboard, and using banjo tuners as a de facto slide-cum-whammy.

But just imagine if you'd never touched that curtain. Press "play" on Cocoon, for instance, and you won't be asking how Gomm did it. The song and the production places his technique within its rightful context, buried in the music and the emotional tenor of his composition.

Here, Gomm talks in-depth about his philosophy with regards his instrument, the limits of technique and performance, and of a new collaboration with Ibanez that he hopes will see production model acoustics purpose-built for these new styles.

The Faintest Idea is immediate, its accessible, and yet it is created using some of the most difficult and unique playing techniques we have seen. How do you set about not making that difficulty get in the way of the song?

“I think what I have done on this album is more accessible, which wasn’t deliberate. In recent years, I have found my values as a human being. There are a few that are important; one of them is that I really care about things being beautiful. Whether you are are a web-designer or bake bread – try to make it beautiful.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I wanted to make it sound beautiful, so what I'm doing on the guitar is mostly geared towards that end, and it is funny, because the way that I play the guitar with all the crazy techniques, that feels like it is so embedded in what I do as a musician now that I don’t really have to think about it. It's almost inevitable that, when I write a new song, I'm going to have some ridiculously complex way of playing it on the guitar.“

The kind of cognitive dissonance between what they are seeing and what they are hearing is almost part of the experience of listening to the song

So this technique, that complexity, it's all just there, and unavoidable by now?

“In some cases, it is more complex than anything I have ever done before! [Laughs] When I get onstage – oh, I can’t wait! – when I get on stage, and I am finally able to play these songs, I think people are going to be a little surprised.

“I know when they see the videos people can be a little bit surprised and the kind of cognitive dissonance between what they are seeing and what they are hearing is almost part of the experience of listening to the song.“

That’s exactly what I was driving at. The music is very simple to digest and experience, yet you see it being performed and it’s sorcery.

“Cocoon is very simple melodically and there is a lot of repetition within the song, so it is not really a confusing thing to listen to. But when you watch me playing it, my hands are crossing over each other, they’re flailing around, and it really looks complex.”

Is there a typical reaction you get when people see this for the first time?

“I read YouTube comments because I find them fascinating. Sometimes I regret it. Sometimes I don’t. Sometimes it’s fantastic. Some people complain – they are consumers and they are consuming [the music] and they complain, meaning they don’t like what they’ve consumed, which is fair enough, but nobody is saying, ‘Oh, this is too complex technically.’

“No-one is saying that, which is what I am really please about. No-one is saying, ‘What’s the point of all this crazy guitar stuff?’ The only thing that people are complaining about – and it is rare, a couple of comments – is the fact that there is too much reverb. ‘I can’t hear the guitar clearly enough.’”

Are you too easy with the reverb?

Cocoon is very simple melodically, but when you watch me playing it, my hands are crossing over each other, and they’re flailing around, and it really looks complex

“It’s not reverb. Well, this is, there’s loads of reverb! But there’s synth on there as well, and all this other stuff that my producer [Andy Sorenson] added, and that’s actually the bit on the album that I am most proud of, that sound.

“Michael Hedges talks about this as well where he would say that people would complain when he did a vocal record because they just wanted to hear the fancy guitar playing. Bob Dylan, obviously, went electric and appalled people.

“I don’t think I have got as much to risk, artistically, as those guys, but it is a thing that I am changing the sound and layering the sounds on top of what I am doing, that some people are going to be resistant to it, but I am really happy that it sounds beautiful and my producer has done an incredible job.“

That makes perfect sense. It is a guitar recording from a certain perspective, but it’s music. Other elements are needed to make it work.

“We have come up with a sound that is quite unique. At this stage, I am really proud of it. If you ask me in a year’s time, I’ll probably hate it like I hate everything else that I have ever done! [Laughs] You never know!”

You raise an interesting point. Sometimes guitar players are not good listeners and get distracted by technique or tone. Do you think guitar culture gets music backwards sometimes?

“The way that I describe that is paradigms. A paradigm being a thing that you keep a perfect example of in your head, and people have a perfect example of music that they want to hear, or guitar playing that they want to hear that exists in their head. They might even have a paradigm of me, a perfect example of me and my music that they want to hear. Paradigms are the death of art and creativity. They should be banished at all costs.

Jeff Beck’s guitar sound is my favorite guitar sound, and it is really weird – he has avoided all paradigms in finding that sound and that is why it's so great

“People have a perfect guitar sound in mind, and maybe it is like Stevie Ray Vaughan’s attack and the sustain of a Les Paul mixed together, and they have this paradigm, and then they’ll try to find that paradigm – but actually, when you get something beautiful, it is actually a unique, expressive voice that doesn’t sound anything like anybody’s paradigm.“

And that is in practice harder to do these days

“Jeff Beck’s guitar sound is my favorite guitar sound, and it is really weird. Nobody really, really tries to copy that – because it's so distinctive, maybe? Or because it is quite hard to achieve. You’ve got to know how to rewire your guitar in that special way or whatever. But his sound is unique and expressive and really obviously him, and he has avoided all paradigms in finding that sound and that is why it's so great.”

We are in a very uncomfortable moment in history where politics only gets more extreme as art grows ever more tame and risk averse. Why have we become risk-averse?

“I think there are lots of different reasons. With the internet, you can discover anything, theoretically. You can discover any music that you want. Whatever guitar playing you want. But you don’t discover what you need, and for anybody who wants to understand music, there are things that you need, that when I was a kid it was kind of like eating your greens.

“There are certain things that you need to understand in order for your knowledge to be culturally rooted, or technically rooted, whatever… I grew up as a kid listening to old music.

“Whether it was blues or classical music, it was a lot of old stuff, and then when you go to listen to new stuff there is a context for everything that you are hearing, and you can trace it through and it gives you a deeper understanding.

There are certain things that you need to understand in order for your knowledge to be culturally rooted, or technically rooted

“It also gives you a deeper understanding of yourself and the world that you live in because you can trace things back to here and there. That is a beautiful thing.

“The problem with the internet is that sometimes you can just find out stuff that you need and so people can dive straight in to learning fingerstyle guitar, and not really look at where it comes from. And it is not that they have some kind of moral responsibility to do that; it’s just that they are missing out on so much by not doing that. I think that can be a problem.”

Yes, a patina of expertise without the sensibility behind it. Too much discovery and not enough understanding…

“That’s a great line, man! Can you put that in and say that I said it? [Laughs]”

You put the words into my mouth. But what you are getting at is that the internet creates a pressure on everyone to be an expert…

“There is a lot of pressure. There is so much pressure to be an expert when you are not. So much pressure. I’ve been there. I remember the early days of the internet, when I was younger, and social media didn’t exist. I would be going on message boards or news groups.

“We'd all be there and it was like, suddenly, we were all free to be less challenged and to kind of cheat at knowledge. 'I have grown out of that. I don’t feel like that anymore.'

The internet has these metrics that have everyone performing in a sense. Does it place similar pressures on the artist?

”That is a thing with music as well; it’s like the pressure to be an expert. To put your music on Instagram – which probably means a one-minute video, and it is visual – the pressure on that to be impressive is enormous, because things that are good, that are beautiful musically, are not necessarily visually interesting.

Having profited from it in the past, I am not trying to achieve the next viral video because it just doesn’t lend itself to making beautiful music

”They don’t get a lot of views, a lot of clicks, a lot of likes, but things that are visually impressive, or have some kind of story behind them that is obvious visually, do. The pressure to get clicks is really huge, and it is a pressure that I have decided to completely ignore! [Laughs]

”Having profited from it in the past with a viral video, a song that had a visual wow factor to how I was playing it, I am not trying to achieve the next viral video because it just doesn’t lend itself to making beautiful music.”

There is something organic and fundamental about acoustic guitar, and you seem to both acknowledge this and resist it, bringing in synths. How do you hold these two elements in tension?

“There are two things. Firstly, with synthetic music, with synth-based music, let’s say, there are things you can do to build emotion that are kind of orchestral. You can make things huge and all-encompassing, in a way that you just can’t do with a guitar. Sonically, you can’t do it.

“But also, what I am trying to do with the music is generate as much emotion as possible through the lyrics, through the notes that I am playing. Marrying that with synthetic sounds that can build and envelope the listener just makes perfect sense.“

“The other side of it is the sonics. I think the acoustic guitar is the most versatile instrument that exists, especially the modern fingerstyle way of playing it where you are using percussive sounds, you're tapping, and there are so many different timbres inside one box with strings on it.

“But there are things that you can’t do, and one of those is swells. You can’t make something get louder, so that once you have played it, everything that you play is then going to get quieter. You can’t avoid that. You can’t defy the laws of physics. Also, the EQ of the sound, I try to get as much midrange into my guitar sound as possible to make it sound as full and as fat as possible. But there are limits.”

You can only add so much.

I try to get as much midrange into my guitar sound as possible to make it sound as full and as fat as possible

“It was interesting when we made the album and then went to mastering. The mastering engineer at first scooped all the midrange out and made it sound more like he thought maybe an acoustic album should sound, and we had to go back to him and say, ‘No, all that fat midrange, that you think, oh my God, it sounds maybe muddy… That’s what we want.’

“All that fullness and richness is what we spent a long time on! [Laughs] We went back to square one and once the mastering engineer understood artistically what we were trying to do then it was easy, because he is very, very good.”

The guitar is a midrange instrument and we tend to have a difficult relationship with them always boosting or scooping. But once you fix your mids, more often than not you have found your sound.

“I think so, too. It is something that is overlooked a lot because people like the sound of the sparkling treble and the low bass, so they need to be there. Certainly, the treble is not hard to achieve with the steel-string acoustic guitar.

“You can build the cheapest, worst steel-string acoustic guitar and it is going to have plenty of treble. You don’t have to worry about that. When you are designing or building an acoustic guitar, trying to find the bass is more difficult, and then the midrange is something that you have got to tune and it takes a lot of skill and a lot of knowledge – and sometimes some trial and error to find that sound.”

Do you still use 14s, and does that string gauge help you find a certain amount of body in your tone?

“Yeah, it does to an extent. I tune down and I use very heavy strings. I also don’t have nails on my right hand because I just think there is enough attack already on steel strings, and I like tapping so much. Sometimes I’ll do eight-finger tapping – pseudo-Stanley Jordan tapping – so I don’t like having nails.

“That means that I end up having more midrange because I am hitting the strings with my flesh. The strings help a little bit but really it’s the guitar. It’s the woods. It’s the size of the body. That makes a big difference. And then there’s the bracing of the top. That makes a big difference.”

You’ve partnered up with Ibanez. What did you record with?

I always gravitate towards Ibanez because, in the '90s, their signature models were the guitars that I coveted more than anything

“I recorded most of the album with a prototype of an Ibanez that we have been designing for a while. It was kind of a strange thing when Ibanez approached me.

“I went to the Ibanez booth at the guitar show in Germany and I always gravitate towards the Ibanez booth because, in the '90s, when I was a kid, the Joe Satriani model, the Steve Vai model, the Paul Gilbert model, the Frank Gambale model, which has now morphed into the S-series, those were the guitars that I coveted more than anything, and I still kind of do.

“I remember at this show playing a Joe Satriani model. They let me noodle on it for ages, and this guy, who I think was head of Ibanez Europe or Germany, came over to ask me if I was interested in playing their guitars.

“I told him, 'What Ibanez did with electric guitars, where they provided instruments that enabled these new, technical, progressive guitarists to get the playability and sound they needed for their music, Ibanez should be doing that right now with the acoustic guitar revolution that is happening right now. In terms of people’s technique, people being experimental with the guitar. Call me back when you're doing that.'”

No messing around. Tell it to them straight.

“[Laughs] I really meant it! It meant a lot to me emotionally that a company like Ibanez, which I saw as being a progressive company, and I really wished that they were doing that – and to be fair, nobody is.

“Incredibly, a few weeks later, I got an email from Ibanez asking me to help them, or talking to them at least about coming up with a guitar designed for modern fingerstyle. And so I did. We spent a long time designing it and it's really incredible what they've come up with.

“I told them what it needs to be able to do, what it needs to be able to sound like – not what it needs to sound like but that, 'These are the sounds that people are able to achieve, so can you do that in a mainstream instrument?'”

What holds you back from getting these sounds on a regular acoustic?

I really hope that this style of playing will become more popular because people will be able to get a guitar that's designed for it

“The problem with a lot of guitars that me and my peers who are well-known fingerstyle guitar players have is that we're playing guitars that are quite difficult to get, because they're handmade – maybe handmade in a very small workshop with very few people and they don’t make many guitars. It's really hard to get them.

“I really hope that, if a guitar comes available – and hopefully the Ibanez modern fingerstyle guitar will be popular – that this style of playing will become more popular as well, because people will be able to get a guitar that's designed for it, that will work, and will produce those sounds that they hear on YouTube. They’ll be able to do that at home because the guitar is right and the pickups are right. Then that style of playing will become more popular and evolve.”

Can you talk a little about the spec? Does your Ibanez have banjo tuners?

“That’s quite niche. In terms of getting my sound, they don’t matter at all but I think we would probably include them as an option. The bracing pattern will be different to what you will get on the vast majority of widely available acoustic guitars. The body shape is completely unique and something we came up with.

“There are things like the neck, the scale length – I'm not sure exactly what I'm allowed to say in detail, but the scale length will be different. Basically, it's got a lot of low bass; the term that is sometimes used in the acoustic world is 'piano bass'.

Is the feel different?

“There are frets that make tapping, hammer-ons and stuff – which is a big part of modern fingerstyle – a lot easier to do, and people don’t necessarily realize that, I don’t think. It's the shape of the frets, the material of the frets. There are things within the neck to make it more stable, so if you're changing tunings between songs you're not going so out of tune.”

It seems strange that the big companies haven't developed a modern fingerstyle acoustic for the production line before.

“Most of the big acoustic guitar companies work within their own world. They have their own brand, their own style of guitar that people expect them to produce. They have their own market and they haven't really shown any interest in a modern, progressive design. It has been left to boutique luthiers to do that, so hopefully, with this guitar, we can make some of those ideas mainstream and available. That’s the idea.”

It is a great idea. What acoustic guitars need next are better names. Jazzmaster, Stratocaster, Telecaster… Flying V. Acoustics have two letters and a number. It’s not very sexy.

“You know what? Ibanez don’t name their guitars. Usually, they're all letters and numbers. Even the JEM only has a name because the three letters spell, J, E, M, so… I don’t think it’s going to have a name! [Laughs] I’ll have to talk to Ibanez about that.

“I’ll tell them what you said and we’ll see. It’s not too late. ‘Hey, guys – let’s brainstorm names.’ Start brainstorming names, though, and things quickly get very Michael Scott/Alan Partridge… ‘Excalibur!’ [Laughs]”

- Jon Gomm's new album, The Faintest Idea, is out now via KSCOPE.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to publications including Guitar World, MusicRadar and Total Guitar. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)