Wilco’s John Stirratt: “With the bass, you can change the tone of different parts... I try to find a really good rhythm track that aids the melody”

Stirratt tells all about a febrile writing and recording session that found Wilco tracking live in the room and heading in a cosmic country direction just like Waylon Jennings

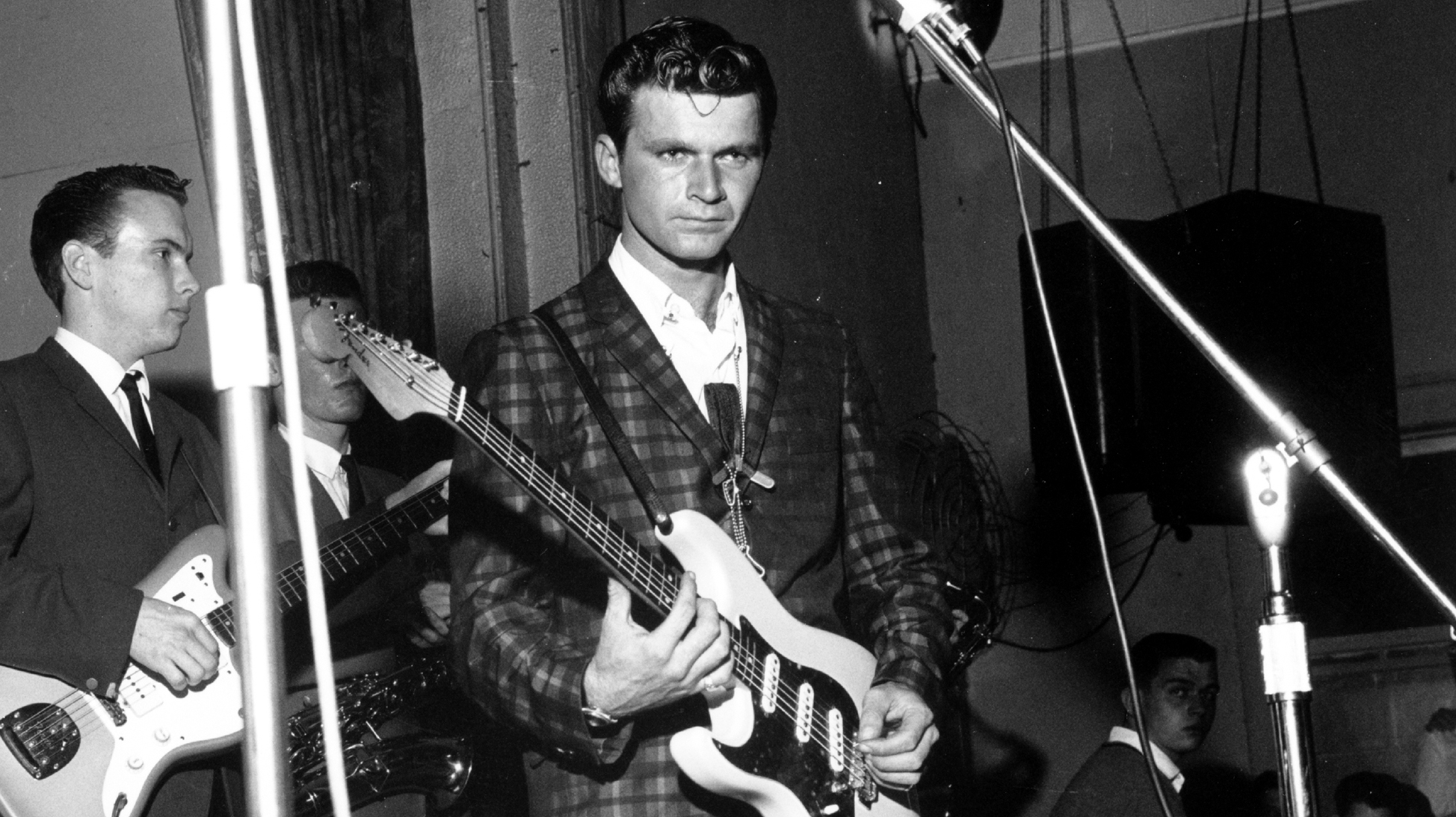

John Stirratt is one of the best bass players you’ve never heard of. He has served as the steadfast foundation of Wilco, a band that has shaped our definition of rock, alt-country, and indie music for nearly three decades.

Standing alongside Jeff Tweedy since Wilco’s inception in 1994, he has received two Grammy awards and industry accolades, headlined festivals and toured the world, and recently recorded their twelfth studio album, Cruel Country. Stirratt has made a career as the bass player in a rock and roll band – something that many of us have aspired to do.

As with most bands, the first few years were riddled by landmines: Ego trips, label feuds, rigorous touring schedules, and personnel changes. By 2004, Wilco finally settled into their current line-up, a six-piece ensemble that could instantly go from chaotic noise and grizzly guitars to an exposed acoustic sound accompanied by vulnerable vocals.

With hard work, consistent output, and the willingness to defy industry standards, they’ve anticipated the needs of their audience and continued to reap the benefits of longevity. They’ve never had a hit song or topped the charts, yet they’ve proven time and time again that if they make a record, the fans will listen.

2021 marked the twentieth anniversary of Wilco’s industry-disrupting and critically acclaimed record, Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, which they’ve taken to re-releasing and performing in full. It’s only fitting that they follow this milestone with Cruel Country, a new double LP that recently debuted at their Massachusetts festival, Solid Sound.

The creation of this record took advantage of The Loft, a Chicago-based Wilco clubhouse that serves as a creative playground, studio, and gear-filled wonderland. For the first time in years, the band recorded live and with all members on the studio floor.

This old-school method meant that Stirratt had to carefully select gear that would work within this setting. While his go-to bass guitars typically include a few vintage Precisions, a ’65 Fender Jazz, and a ’73 Les Paul Signature, this record called for something slightly different.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I wanted to hold everything down, given how much instrumentation was going on: Acoustic guitar, two electrics or two pianos, and drums. I’ve had a Guild Starfire since recording the album Being There [1996] and I’ve always come back to it for this sort of mid-tempo, acoustic-style bass. It’s got an incredible bottom end when played with fingers, and when I play it with a pick, it’s got a wonderful, woody sustain.

“I was also using an Epiphone Embassy bass. It has the same pickups as a Thunderbird, but with a cutaway and a massive low end, and I also bought an ’80s Rickenbacker that was really useful on a couple of songs. I went with these basses because there were a lot of competing frequencies when using Precisions.

“With this material, and the band recording six at a time, Jeff was playing a lot of acoustic, so I was looking for the boomiest basses I could find. Plus, I played a B-15 throughout the whole thing, so that was fun.”

With this material, and the band recording six at a time, Jeff was playing a lot of acoustic, so I was looking for the boomiest basses I could find

Regarding inspiration, Stirratt referenced classic country recordings and the concept of tic-tac bass, a style of playing that involves doubling or mimicking the sound of an acoustic bass guitar.

“I think one of my favorite bass sounds is Bee Spears’ tone on Honky Tonk Heroes [1973] by Waylon Jennings. It’s a super clicky, picky bass, almost like they’re trying to approximate a tic-tac bass.

“As we were working on a few songs, I was playing with a pick and sponge, and it was a big enough ensemble that it needed something broad and really full-range. I grabbed the Guild and the sonic scope of it just sounded right. I also listened to George Jones and Tammy Wynette records, music from the English folk scene, and to players like Danny Thompson and Dave Pegg.”

Thinking back to some of his favorite bassists, Stirratt cites the studio giants known for their melodic sensibilities. “Joe Osborn is one of my favorites, without a doubt. He’s a player that you aspire to be like. His playing on Simon and Garfunkel’s Bookends [1968] and Bridge Over Troubled Water [1970] is just so enjoyable; all of the counterpoint is amazing.

“There’s also Tommy Cogbill. I remember hearing Son Of A Preacher Man when I was really young, and the bass completely moved me. I also have a real appreciation for Lee Sklar’s work in the ’70s, especially the smooth, nuanced finger-style playing on Gene Clark’s record, No Other [1974]. And then there’s Chris Hillman, who inspired me to buy a Guild Starfire in the first place. It’s amazing how he just picked up the bass as a beginner and did what he did with the Byrds.”

I’m still trying to learn Beatles bass parts: I go back to them whenever I can. That should be required, I think, for every bassist

“McCartney will always be the gold standard. He writes songs within songs on bass, with amazing melody and muscle. I’m still trying to learn Beatles bass parts: I go back to them whenever I can. That should be required, I think, for every bassist.”

Thanks to his obsessive musical knowledge and plenty of experience in the studio, Stirratt goes into the session with a goal in mind.

“I try to provide a good rhythm track with Glenn [Kotche, drums]. Alongside his innovation and creativity, he also has a great pocket and feel for what the song needs. It has to be something that can be built on by the other instruments.

“With this record, I was very intent on keeping the right vibe – giving people something substantial to play off of, and guiding things with a certain direction and feel. I do think that with the bass, you can change the tone of different parts and decide to be more flowery or sparse. I try to find a really good rhythm track that aids the melody.”

Stirratt also has an aptitude for chord inversions and recognizes how flexible the harmony of folk music can be. This stealth tactic takes a familiar sound and adds color by nudging our ears toward something other than the root note.

Referring to the song Handshake Drugs from A Ghost Is Born [2004], Stirratt mentions how working with producer Jim O’Rourke inspired him to “find something memorable that really starts from a different place. There’s a lot to beginning on a fifth or a third and trying to work your way down to where the root is.” This approach was put to good use on the Cruel Country tracks Many Worlds and Country Song Upside Down.

Crafting parts and harmonizing alongside Jeff Tweedy, both as a vocalist and as an instrumentalist, has gotten easier over time.

“There’s a second nature thing about playing off of his voicings. It’s really innate. With Jeff playing all acoustic on this record, it’s a very comfortable place for me, and I can often feel where he’s going. There are interesting parts and I’m playing off of the arpeggiated stuff that he does.

“A lot of the mid-tempo stuff is in our DNA and has been established for a long time, since Being There. Even singing with Jeff, I can make my voice sound exactly like what it needs to be. We’ve got this brotherly thing happening after all this time.”

Crafting parts and harmonizing alongside Jeff Tweedy, both as a vocalist and as an instrumentalist, has gotten easier over time. “There’s a second nature thing about playing off of his voicings. It’s really innate. With Jeff playing all acoustic on this record, it’s a very comfortable place for me, and I can often feel where he’s going. There are interesting parts and I’m playing off of the arpeggiated stuff that he does.

“A lot of the mid-tempo stuff is in our DNA and has been established for a long time, since Being There. Even singing with Jeff, I can make my voice sound exactly like what it needs to be. We’ve got this brotherly thing happening after all this time.”

I think it’s the magic of a take, frankly, beyond anything. It’s the chills that you get when you come down on the last note or when you listen to the playback... That’s the drug, for me

Even though they can anticipate what might happen, there’s still a mystical element that keeps Stirratt returning to the studio. “I think it’s the magic of a take, frankly, beyond anything. It’s the chills that you get when you come down on the last note or when you listen to the playback. You think ‘This might be pretty special’. That’s the drug, for me. It’s trying to find magic in the air and going after that. It’s what makes everything else worthwhile.”

Capturing that magic often happens quickly, especially when recording with everyone on the floor.

“With Wilco, things happen live, and the first take could really be the take. We talked about it not being unlike a Nashville session. When we started to take on more of a cosmic country direction, we realized that so many of the records we liked were done this way – pretty fast – and I think the Buck Owens or ’70s Waylon Jennings records were like that.

“Plus, Jeff had great live vocal takes and this material really lent itself to that. I think that now, we work so much faster and we’re just better at what we do.”

And they really have been working together for a long time. Making a lifelong career of playing in Wilco isn’t something that came easy. Like any band, their success didn’t go in a straight line: It took almost a decade to find the right collection of players.

“Going back to the ’90s, it was no holds barred, substances, and the gamesmanship that happens with kids in bands. Around 2005, we were getting out of that. We didn’t have the aspects that you have in young bands during their first few years – the power moves or Machiavellian stuff going on. It’s really been incredible.

“We’ve had this ‘third act’ for 18 years now and I feel like I’ve grown with this line-up. It’s wonderful to have this camaraderie with a larger group and to work on your craft and your own instrument. We have it so good in a way, with an older, more traditional rock and roll mentality.”

Playing with a different rhythm section keeps you sharp and gives you different ideas

When the band isn’t on the road, each member continues to seek out musical opportunities – an extremely important aspect for growth and continued creativity. Upon reuniting, they bring that experience to the stage and studio.

“Pat Sansone is doing Nashville sessions, Nels Cline is in the jazz world, and there’s a sharpness that people bring back to the situation. It’s all learning, it’s all experience. That’s what I’ve always really loved. Playing with a different rhythm section keeps you sharp and gives you different ideas. Some of the times I’ve been most stifled is when I couldn’t converse or have musical conversations with other people.”

Now that they’re hitting the road again, the task of learning material for festival dates and touring season can be an intimidating task. In addition to working through Wilco’s material, Stirratt is also getting reacquainted with music from The Autumn Defense, a side project with multi-instrumentalist Pat Sansone.

“The catalog is huge, and I do find that any sort of playing helps with muscle memory and the connection of old material. Even as I’m learning songs, I’m just playing a lot. In this situation, I’m learning 21 songs: The whole new record. The preparation is daunting in terms of the amount of material, and there are covers to learn too.

“I like to work on stuff in the early morning; I tend to wake up and run the material a couple of times because that’s when I retain the most. We also get vocal stems and I drive around and learn the vocal parts. That’s something we weren’t able to do before, so it’s pretty deluxe to have that now.”

Despite all of the time and preparation that goes into touring, Stirratt still has a bucket list and sincerely appreciates the band, crew, and fans for showing up time and time again.

“Iceland is somewhere I still haven’t played, and I’d love to get to Africa sometime. I love going to most of the places and they’re still really magical to me – even the Midwest and places we’ve been to a million times. The support from the fans and the crew is great; it’s always been this culture in and among itself.

“There’s a heavy social implication to it, and the fans get together and it’s beautiful. The crew is like that too. I’d like to say that it’s a reflection of the band, but it’s even more than that.

“We can’t believe this is still happening and I have to say how fortunate we are,” he says. “No-one could ever ask for more.”

- Cruel Country is out now via dBpm Records.

“When I first heard his voice in my headphones, there was that moment of, ‘My God! I’m recording with David Bowie!’” Bassist Tim Lefebvre on the making of David Bowie's Lazarus

“One of the guys said, ‘Joni, there’s this weird bass player in Florida, you’d probably like him’”: How Joni Mitchell formed an unlikely partnership with Jaco Pastorius