Joe Satriani Discusses His Approach to Composition —and How Every Song Remains a Work in Progress

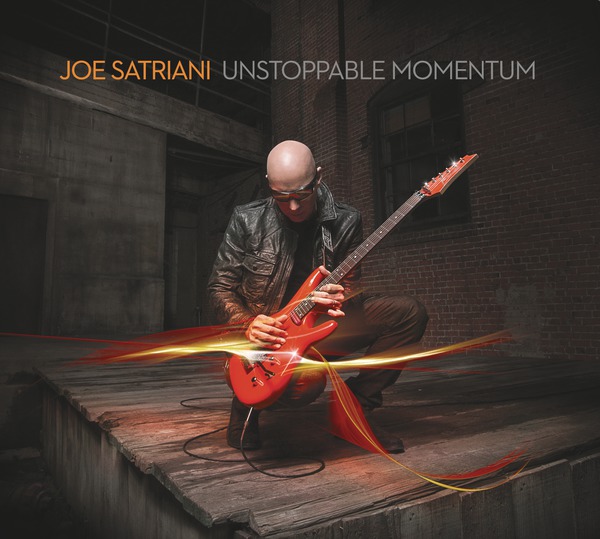

In support of his 14th studio album, Unstoppable Momentum, Joe Satriani is spending September and October on tour in the US.

Joining him are longtime band member/keyboardist Mike Keneally, and a new rhythm section: bassist Bryan Beller and drummer Marco Minnemann.

Although he is recognized as a virtuoso, Satriani views his relationship with the guitar as much more than the mastery of technique. His focus is on songwriting — creating melodies and drawing his audience in with instrumental storytelling, rather than showing off speed and flash.

He recently discussed his approach to composition and how each song remains a work in progress.

GUITAR WORLD: What does it take to be your band member?

I don’t know. I never think of it that way. I think there’s a lot of synchronicity in play. If somebody mentions somebody, or in this case, I started playing with Mike a few years ago because I was looking for a keyboard player who could play guitar really well, only so they would understand what I was going through as the soloist. Mike popped into my head at the last minute.

Getting Mike in the band introduced me to Marco, because I hadn’t really known about Marco until I was riding on a tour bus in Europe with Mike and he would say, “Check out this thing I just did with my drummer Marco Minnemann.” I listened and I thought, Oh my god! This guy is insane. One of these days I should play with him. So sometimes it’s just like that. It’s a combination of free association and synchronicity and you wind up playing with people. It’s not like you hold auditions or anything like that.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The title track is also the longest track on the album, at 5:14. In this era of 140 characters and six-minute online videos, are you battling shortened audience attention spans? Do you write and sequence the albums and shows with that in mind?

Never, no. I never thought of it that way. I do what I think feels best. I take every song as a unique opportunity to develop a strong melody, and if it calls on any special techniques or arrangements, then I will use those. I don’t think about anything else, other than does it sound and feel right to me, am I telling the story truthfully, am I getting the emotion of the story right. After that, if the song is too short or too long, then so be it.

Is songwriting, or performing, a visual experience? Is there an image in your mind when you’re creating the music?

Certainly, yes. I think every song has got a series of movies in my head that kind of guide me to edit the melodic content appropriately. I’m always afraid that there’s going to be too many notes or too few notes, and if I’m writing about a particular person or event that I’ve experienced, or even something that I dreamt up, I’m putting the music up against those images in my mind and making sure that they correlate completely.

How close do you come the original idea? Does the song sometimes take a completely different direction from what you thought it was going to be as you began to connect the melody and the imagery?

Yes, sometimes. We’ve put out a lot of songs, and over the fourteen studio albums there have been some crazy excursions in songwriting, but I never get the feeling that I’m finished, really. I have to say that I’m saved by the touring, because the albums kind of get abandoned because you run out of time and money, which is probably a good idea to force us to stop tweaking on it. When I’m out on tour, I get to work on it over and over again, so in many ways I’m still working on songs from the first couple of records because we still play that stuff.

Every night I play “Satch Boogie,” I try something different with it and I ask myself, Is that better than what I put on the album? The albums usually are your first attempts at playing something, so if it’s a physically difficult piece, the album actually is a document of you playing it when you’ve had the least amount of experience with it.

Twenty years later, if you’re still playing it live, you’ve had all these years, two decades, to practice it, to learn the alternate fingering, the better place to feel it, so for me, the catalog is always something that I’m still working on. I don’t view it as something that I finished, let’s say, fifteen or twenty years ago and I’ve stopped working on it. I’m always working on it.

When and how did you learn to be musically flexible?

I’m still learning that. I don’t think I ever learned it completely. I think every night onstage I’m trying to bend more and more. That’s a really good question because it makes you ask yourself, Am I flexible enough? You always want to feel like there’s more room to bend into that you haven’t experienced yet, and you want to try to play with people that stretch you. I don’t want to use too many metaphors in a row! The whole idea of it being a stretch sometimes is great. You want to challenge yourself as much as you can.

Photo: Chapman Baehler

Read more of this interview here.

— Alison Richter

Alison Richter interviews artists, producers, engineers and other music industry professionals for print and online publications. Read more of her interviews right here.

Alison Richter is a seasoned journalist who interviews musicians, producers, engineers, and other industry professionals, and covers mental health issues for GuitarWorld.com. Writing credits include a wide range of publications, including GuitarWorld.com, MusicRadar.com, Bass Player, TNAG Connoisseur, Reverb, Music Industry News, Acoustic, Drummer, Guitar.com, Gearphoria, She Shreds, Guitar Girl, and Collectible Guitar.

“I just learned them from the records. I don’t read tabs or anything, I don’t read music – I learned by ear”: How a teenage Muireann Bradley put a cover of Blind Blake’s Police Dog Blues on YouTube and became a standard bearer for country blues

“The Strat was about as ‘out’ as you could get. If you didn’t have a Floyd Rose, it was like, ‘what are you doing?’”: In the eye of the Superstrat hurricane, Yngwie Malmsteen stayed true to the original