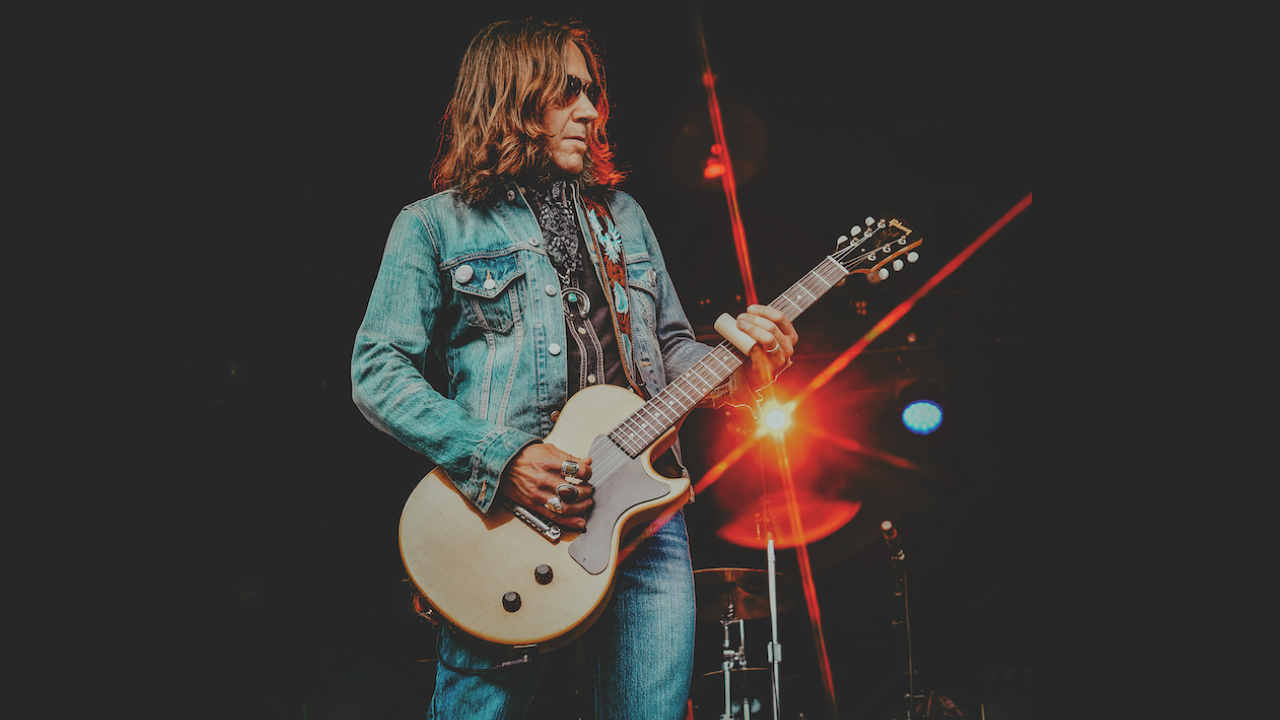

Alt-J's Joe Newman: "I'll never be a John Mayer. I'm one of those people that just explores the guitar – I'm on that journey now"

The songwriter reveals how a newfound appreciation for YouTube guitarists, gear and the instrument itself informed Alt-J's latest folk-leaning effort, The Dream

It has been almost five years since Alt-J released their last album, Relaxer. You’d expect any player to evolve in that time, but listening to the band's frontman Joe Newman on their new album The Dream, it’s clear he’s had something of a revelation.

“I think I’m giving the guitar a voice now,” says the songwriter for the English indie stalwarts at one point in our conversation. Indeed, The Dream’s second track, U&ME, proves that to literally be the case, when Newman weaves in a name check for his “Candy Tangerine Telecaster” on the second verse.

That’s not to say the more seismic societal changes of recent years haven't found their way into The Dream – it’s a record that weaves their self-described art school “cowboy” writing process in and out of themes of isolation, substance abuse, crypto hype and grief.

Relaxer has often been described as Alt-J’s folk album, but in some ways it feels like a tag more appropriate for The Dream – a collection of stories born against a backdrop of upheaval, much like The Dust Bowl, or Civil War eras. The almost entirely acoustic Get Better represents Newman’s most intimate and stark arrangement yet – a guitar-and-vocal arrangement that embodies the loneliness of the time.

However, it’s also an album that reaps the results of Newman’s lockdown woodshedding: of days holed up in his garden studio watching YouTube guitarists, and exploring for the first time the world of gear, tonal obsession and dreamy techniques that proves so addictive to those of us who inhabit that realm.

Newman tell us about his Dream guitars (including a Yuriy Shishkov Masterbuilt Telecaster), the only amp they ever use in recording (spoiler: it was once owned by David Gilmour) and how he, finally, came to see himself as a guitarist.

A lot of people deepened their relationship with songwriting and the guitar across the pandemic period. Has that been the case for you?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Having so much time to focus on the guitar over the pandemic meant that I started appreciating the instrument itself

“I’ve always loved writing. I feel like it's a really nice corner of my life that I can walk into and don't have to worry about anything. So it didn't deepen my love for writing. But I think having so much time to focus on the guitar meant that I started appreciating the instrument itself. I started looking at YouTubers and following famous vintage guitar stores around the UK and US, and I started getting into guitarists like Michael Lemmo [of Norman's Rare Guitars].

“I started watching great guitarists play in comfortable settings, where everyone's just relaxed. I was sitting in my studio – it's a very small space – but it was private and it was a sanctuary. I came to realize that over the 20 years I've been playing guitar, I’ve had a really good foundation and that made me happy. I appreciated I had something to show for it, which is a developing style of playing.”

We’re often hoping to tap into something in ourselves when we start looking for new gear – some sort of self-image we’re trying to attain. What did it mean to you at that point? What were you after?

“I think I liked what I was doing and I started to see myself as a guitarist and not a songwriter. I started going through a long drawn-out fantasy that I was a guitarist as well, and started writing songs that included guitar solos. Then I got good feedback from the band, who kept on wanting to re-listen to my work. And that's it for me: that's the key signifier that you're doing something exciting.

“I was also treating writing solos like writing mini songs. There's a landscape to a good solo and you want to sing a good solo, too. I drew from David Gilmour and also Michael Lemmo. When he plays on Guitar of The Day, he creates these delicious melodies on one string. I wanted to emulate those people because they had perfected the instrument. It felt like if I perfected the instrument, it would also legitimize me wanting to buy the instrument, you know?”

One of the guitars you used a lot was reportedly a Larrivée P-05 parlor, which was used to write much of the album. What is it about that instrument that works so well for you?

“I’ve always liked parlor guitars, because they are movable. I grew up playing big-body acoustic guitars and I don't like having to get my arms around it. And I also like the idea that you can write anywhere with a parlor guitar.

“Also, my dad is always searching for a good bargain and he loves guitars, so you bring those two features together and you find yourself the Larrivée. I love that guitar. I've got so many nice guitars, though I'm always I'm always secretly like, ’But it plays best on this Larrivée.’

“Currently, I've been doing a lot of writing on this Gibson ES-330 single pickup. It's the first Gibson I've ever owned and it's from 1961. I play that all the time and I'm dedicated to the idea that it will be played on the next album. But there are songs that I play on that I think I’d prefer to play on the Larrivée…”

Do you always have that argument and then wind up going with the Larrivée on the record?

“Well, what normally happens is that the Larrivée is there to double up on all of the electric guitar that's played, unless it's a pure acoustic song. But the reason why I don't use a Larrivée is because you can't go very far up the neck before you're in struggle, er, town…”

We all know struggle town!

“Yeah. And you don't want to get lost in an unnecessarily difficult action when you can just do it on the ES-330 and it's fine. Plus, there's something nice about playing something that's really fucking old, so I do love that guitar [as well].

Playing electric guitar is the treat after you've got through the main course of playing the acoustic

“I think the Larrivée is like an emergency guitar that I keep in the house, but it’s also the guitar I use the most. Then I always find that playing electric guitar is like the treat after you've got through the main course of playing on an acoustic guitar.

“Even when I was younger, my dad had all these Ovations in our house and I would diligently play them because they hurt my fingers! I knew that, ‘I’ll learn this on the acoustic so that when I play it on the electric, it's just easy and fun and sounds good.’ I think maybe that's why everything starts on the acoustic. That's built into me.”

It’s interesting to note you double-track the electric and acoustic sounds. It explains that thick, percussive finger tone in your recordings.

“I think one of the other nice, stable things about the albums to date is that we've only ever recorded through one amp. It’s a late ‘60s Vox AC30 and I believe it was it was owned by [Elvis Costello and Madness producer] Clive Langer. Our producer Charlie Andrew used to work with Clive and is now the custodian, but before Clive owned it, I believe it was David Gilmour’s.

80 percent of The Dream was re-amped through the Vox AC30. Vocals, drums, bass, backing vocals, guitar... everything goes through it

“All of the guitar parts from An Awesome Wave to The Dream have been played on that amp. But on this album, about 80 percent of what was tracked was re-amped through the AC30. So that's vocals, drum parts, bass, backing vocals, guitar... everything goes through it.

“It's never left its tour case. It has been taken off at the top and bottom, and you've got this foam that's disintegrated into the back of the amp and into the grill at the front. It's been fixed a few times, but no one's touched it because the aesthetic holds the soul of the amp. So we just decided we want everything to go through the amp.

“A lot of Alt-J’s guitar sound has also been that amp with the tremolo on it. There’s just this kind of dustiness, you can almost feel it between your fingers. It's like silk.”

Let’s talk about the song Get Better, which was written during the pandemic and documents a story of grief. It feels like there’s a folk ethos throughout the album but it’s most pronounced there. Why did that seem right for that particular song?

“I think we saw Get Better as a poem. It's the only song where I can get just as much from reading it as I would from listening to the song, so we wanted to strip that back. Folk music has been a pillar of what we have done to date. Gus comes from an English folk background and we grew up being huge on Irish folk. It's a story being passed down, isn't it? That's the whole tradition of imparting information or fables to the next generation, so we saw this as an opportunity to do something similar.

“I said to Gus, ‘I’ve written a really, really sad song.’ And he said, ‘It's okay!’ I was a bit worried about it, because it carries so much weight and I thought, ‘Will people feel I'm a charlatan if I release this, and it's found out that I didn't experience this?’ And he was like, ‘You don't need a doctor's note to write a sad song.’ So I took that and I went with it.

“For me, as for most people in this world, the fear of losing someone is something that you think about in different volumes throughout your day, or throughout your week or your year. It's there. And so, over time, I'd collected all of these bits of writing.

“When we were in lockdown, and you're seeing in the six o'clock news this death tally going up... all these unexpected deaths, of people dying of this previously non-existent virus, which is all of a sudden claiming lives and ruining families.

“It felt like almost everyone was going through something like this. So I played it to Gus, the keyboardist, and he started crying. And I was like, ‘Oh, gosh, this is a good song…’”

Were you concerned about writing a ‘pandemic song’? What made it work, do you think?

“It came about organically. It wasn't my intention to write a song like that. I'm very aware that there's this desire for some to be the first voice that defines the crisis and, if you're looking at it like that, you're doing it for the wrong reasons. You want notoriety – and that's not how you win hearts and minds.

“For me, it took a long time to discover I was writing a song about it. It was kind of an abstract period of time, until I decided to pay tribute to the frontline workers. I’m always moved by the mundane ways in which bravery occurs in real life and I wanted to acknowledge them because I was moved, as we all were, for everyone who was going to work on the frontline.

“But I don't think we can really comprehend the poignancy of this period until we have time to look back on it from a distance, in a period of relative normality. So as much as it's a song that was written within the pandemic, I would say it was more of a song about someone coming to terms with the unchangeable fact that life continues, with or without ‘x’.”

What other gear were you using on the record?

“There are four guitars on this album. I only had the Larrivée when I started watching YouTubers like Rhett Shull and Michael Lemmo and stuff – all my Teles were in lock-up – so I was like, 'I'm a guitarist. Fuck it, I'm going to buy a guitar.’ I bought a Custom Shop Nocaster, and I bought it because I loved the color: it was Candy Tangerine, but it’s also one of my favorite guitars to play. That's on a lot of the album.

“There's also a 1962 [Fender] Stratocaster that I bought for half-price, because in the '70s someone painted it in black car sealant. The guy, who is an engineer, rewired it with a Yamaha pickup, but he was like, 'This is the best pickup, I guarantee. I don't want to sell this, I have to... but it's the best Stratocaster I've ever played.' I was just like, 'Fuck it. I'm writing an album. I want to put this on there, and I want to give this guitar voice.'

“Then the other was a Masterbuilt Yuriy Shishkov Tele. It's built like a Les Paul [with a mahogany body and set neck, ebony 'board with block inlays and two humbuckers]. But it's this Tele-Les Paul [hybrid] thing. It’s the best looking guitar I own, but I play it the least.”

Is it so nice that you're afraid of it?

“It's fucking heavy. And it's the neck – it's all in one. So I can't take it on tour because I don't want to crack the neck. It’s got gold hardware and the finish is like white chocolate and I just love it. There's a guitar solo on this album, on a song called Powders, which I played on this. So I am married to this guitar.

“And then there's another guitar. It was a Jimi Hendrix Anniversary Strat that I ended up giving to my dad. And I played Happier When You're Gone on that."

So is this period the first time you’ve really dug into choosing your own instruments?

“That’s right. I think there's something really satisfying about players that respect their instrument and can play it fluently, those who are passionate about the world of guitars. It's nice to think that I could play my way into that realm if I worked hard.

“I'm not there yet. I’ll never be a John Mayer, but I'm one of those people that just explores the guitar and will find something that's worth other people listening to. That's how I see it, and I'm on that journey now – as I think I was once with my voice – with the guitar. It's nice to know that I've got an extra-curricular activity planned for the next 10 years!”

- The Dream is available now.

Matt is Deputy Editor for GuitarWorld.com. Before that he spent 10 years as a freelance music journalist, interviewing artists for the likes of Total Guitar, Guitarist, Guitar World, MusicRadar, NME.com, DJ Mag and Electronic Sound. In 2020, he launched CreativeMoney.co.uk, which aims to share the ideas that make creative lifestyles more sustainable. He plays guitar, but should not be allowed near your delay pedals.