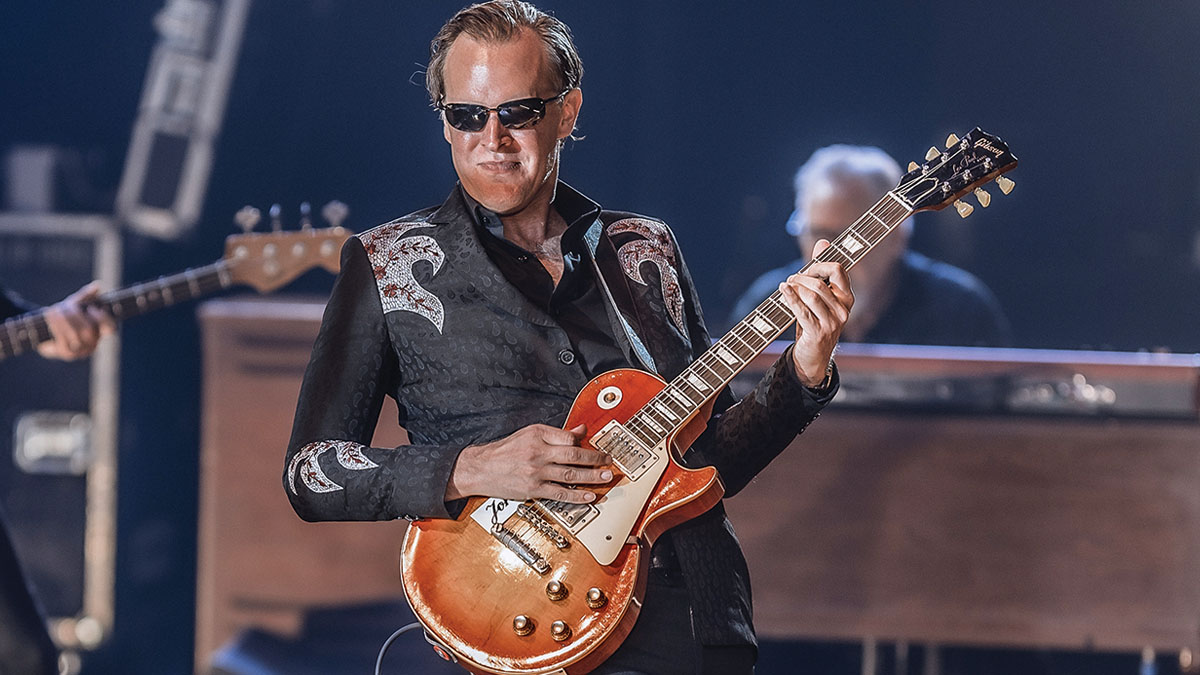

“90 percent of my guitars are in mint condition – untouched and unmolested... The last 10 percent – those are the ones I play on the road”: Joe Bonamassa on his legendary collection, perseverance, and how he picks his touring guitars

The blues guitar titan looks back on the 2003 album that saved his career, explains why – 20 years later – he's recorded a sequel, and reveals how his legendary guitar collection gave a new voice to slept-on blues tracks

Over the past two decades, Joe Bonamassa has been a familiar face in these pages, as a widely appreciated, virtuosic blues guitarist, as well as an avid caretaker of the instrument’s legacy, who has collected and preserved not only hundreds of guitars, but also mountains of classic amplifiers and guitar ephemera.

As such, it might be difficult for readers today to imagine a time when he was just another struggling guitarist trying to make his mark in music. But after being ushered into the ranks of B.B. King and Danny Gatton before age 13, and forming the band Bloodline with Waylon Krieger, Erin Davis, and Berry Oakley Jr. – the sons of Robby Krieger of the Doors, Miles Davis, and the Allman Brothers Band bassist – Smokin’ Joe Bonamassa, as he was known then, tanked as a solo artist.

And what was his plan B when his high-profile 2000 debut, A New Day Yesterday, and its 2002 follow-up, So, It’s Like That, failed to meet expectations? “Uh, I don’t know, become a cop?” he says today, drolly. Instead of trading his love of the beat for a life on the beat, though, he took the experience as a call to follow his own instincts.

Now that he had some real blues to sing about, Bonamassa went back to his musical roots in search of the spark that lit him up years earlier. He found it, and in turn a rabid audience, with his 2003 covers record, Blues Deluxe, which featured a rejuvenated Bonamassa taking on songs by Robert Johnson, B.B. King, John Lee Hooker, Buddy Guy, and others.

“I’ve had a couple of breakouts,” he says. “I would say in 2003 [with Blues Deluxe], after we started getting some traction in Europe, and then in 2009 when we did the Royal Albert Hall for the first time – that was the real explosion. But everything had been leading up to that moment.”

Blues Deluxe Vol. 2, which was released in October, doesn’t cover the same old ground, though. Backed by his core band as well as a bright and blustery horn section and jump-blues piano, Bonamassa puts his spin on the Peter Green-era Fleetwood Mac roadhouse jam Lazy Poker Blues, Bobby Bland’s soul classic Twenty-Four Hour Blues, and six other blues tunes.

There’s also a pair of originals, one co-written with Tom Hambridge, and the album-closer, Is It Safe to Go Home, written by Josh Smith – Bonamassa’s fellow Guitar World columnist – who also produced the album.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

We talked with Bonamassa about how things have changed for him since his first Blues Deluxe installment, curating obscure cuts from lesser-known blues artists, and, of course, the vintage guitars and tube amps he used to bring Blues Deluxe Vol. 2 to life.

Twenty years ago, Blues Deluxe was something of a last-ditch effort to save your music career. Can you take us back to those days?

“I was on Sony Music and was dropped. By 2003, I had no record deal, no prospects and couldn’t draw a crowd. My manager and I had to make a choice. It’s either we’re gonna close the doors [and] I’ll be a session guy or a road player or whatever. And he said, ‘Let’s just make a blues record and fuck it all,’ you know?

“Because at that point we were listening to consultants, and radio this and that, and it just wasn’t me. So, I made a ‘me’ record, and it was the first record I made that really connected to people. We were very lucky that it connected the way it did. We made the record in seven days with $10,000.

“I thought [doing Blues Deluxe Vol. 2] would be a fun project – pick some songs, do it in the [same] spirit and ask the question, ‘Hey, am I better now or worse now than I was 20 years ago?’ I think I’m a better singer now, and I think a more mature artist, and that’s pretty much [why] we picked songs that meant something, that were a little more sophisticated than the first record; with real strings and horns because we had a budget – unlike the first record.”

Why do you think the original Blues Deluxe resonated with an audience where your first two albums didn’t?

“When an artist stops listening to other people’s advice about what they should be doing and goes, ‘I’m gonna do it my way,’ that’s when you start winning. You have to tap into something in your soul that you believe in, because if you don’t believe in it, how are you gonna get anybody else to believe in it? That’s really what happened, and I think that’s why it resonated at that point.”

When an artist stops listening to other people’s advice about what they should be doing and goes, ‘I’m gonna do it my way,’ that’s when you start winning

There are definitely some more obscure names here than on the first volume. How did you narrow down the tracklist?

“Josh [Smith, producer] had a list, I had a list. We both agreed that we wanted to do Twenty-Four Hour Blues off Dreamer [1974] from Bobby Bland. I wanted to do I Want to Shout About It, because that was always one of my favorite Ronnie Earl songs, and then [Well I] Done Got Over It, the Bobby Parker song. And then we did the Pee Wee Crayton song Win-O. It’s just one of those things where before you know it, you’ve got a record.”

From a guitar-playing perspective, did these songs challenge you in a way that maybe the ones on the first volume didn’t?

“From a guitar standpoint, none of it’s giant stuff. I mean, you just gotta play the blues, you know? But when you’re 25 and nobody gives a shit, you’ve got two chips on your shoulders.

“When you’re 45 and established, you’re not so keen on just ramming your guitar prowess down everybody’s throat all the time. To me, the challenge is mitigating those urges to overplay, but really stinging the notes and making it say something.”

When you’re 45 and established, you’re not not so keen on just ramming your guitar prowess down everybody’s throat all the time

How do you think you’ve grown during the two decades the Blues Deluxe albums bookend?

“I’m more seasoned, and you hear things differently. You phrase things differently. That’s one of the most obvious differences between [now and] 20 years ago. My voice is clearer, it’s higher, and it’s just because I learned how to sing. When I was 25, I didn’t know how to sing. I was shouting into a microphone and wondering why it sounded so rough. But then I took all the lessons and figured it out.”

When in your life did a name like Pee Wee Crayton come into play?

“Before I heard Pee Wee’s music, I saw a picture of him holding a very rare ’55 Fiesta Red Strat that Leo Fender built for him. He was an L.A. guy, and the guitar is a very famous guitar, which is at the Blues Hall of Fame Museum in Memphis. He had a run from like, ’58 to ’61 – those were his years, and he was a big star in the blues community.

“He had a great way of phrasing and playing and singing, and just the song structures I thought were cool. He’s just one of those guys that, once you do the deep-dive into the late-Fifties blues, his name will always come up.”

I use those vintage Les Pauls and Teles and Strats and 335s because I want to get the right sound for the music

With your extensive guitar collection, you’re able to bring anything to the table. When revisiting the Blues Deluxe concept, did you dig back into your gear vault?

“Well, I didn’t use the Jubilee Marshalls. I still use them live, but I basically used a high-powered tweed [Fender] Twin, a Dumble-modded Fender Vibrolux with an Ultraphonix mod, and a [Marshall] JTM45 with a 4x12. And then for the two or three songs we cut in Nashville, I used the 3x10 Fender Bandmaster 1956 and a low-powered Twin 1956. But I use those vintage Les Pauls and Teles and Strats and 335s because I want to get the right sound for the music.”

Also, you recently acquired the famous Norman Harris Broadcaster. That’s a pretty important piece, not only for Fender but for the electric guitar in general.

“There’s two things about Leo Fender. He got so many things right the first time – like, a Broadcaster is essentially a Telecaster. But because of a gentleman’s agreement between Fred Gretsch and Leo Fender, they dropped the word Broadcaster. So a Nocaster is essentially a Broadcaster, but they cut the word Broadcaster off the logo. They call them clipped logos.

“By October of ’51, with the television now becoming a thing, they renamed it a Telecaster. Now, the difference between an October ’51 Telecaster and a Broadcaster, other than a very few things – like, the knobs were taller in ’50, whatever – it’s essentially the same guitar. But when you see Broadcaster on the headstock, the price goes up because it is a ’50, and it does represent the first-year DNA.

“Now, that guitar is 73 years old and just as relevant today as it was 73 years ago. There’s not many things that have ever been designed, not just musically, but in general, that could say that. I mean, cars don’t look the same, houses don’t look the same, you know what I mean?

Broadcasters are a very important guitar in the sense that it represents the beginning of a historical journey in American manufacturing

“Things have moved on. Yet, for some reason, the Telecaster, the classic-design Les Paul, which to me is a ’57, the Stratocaster series two, gen-three P-Bass with the Strat head, the Jazzmaster, the Jaguar, all this stuff didn’t go through a lot of delineations. Leo got it right the first time.

“The Jazz bass, other than the stack knob versus the three-knob configuration, it’s essentially the same. So the Broadcasters are a very important guitar in the sense that it represents the beginning of a historical journey in American manufacturing.”

What is in your current circle of favorite guitars?

“Ninety percent of my guitars are in mint condition, untouched, unmolested. Perfect museum grade. Then there’s about 50 to 60 guitars that are the last 10 percent, [which] are the ones I play on the road. Those are more beat up. So, as a collector, you have to go, is your ego large enough to take a mint ’54 Strat and put some scratches into it on the stage? I was like, no, you know?

“For me, that thing’s been preserved for 70 years, and it’s my job to keep it preserved. Am I lucky enough to have another one that’s beat up that I could play? Absolutely. So I have to thread both lines. I’m a player first; that’s what affords me the guitars. But I also have to go, ‘Okay, this is gonna be for the collection, this is gonna be for the stage.’”

There are so many covers records now, full of songs that are well-worn paths. I don’t need to add to the noise

Were you true to the instruments played by the artists you were covering?

“Yeah, I busted out the Flying V for the Albert [King] thing. Albert used the ’67 on Born Under a Bad Sign, and the Korina, but he had three. And so I actually ended up using my ’67 sparkling burgundy V that’s in mint condition on the record.

“I had the [1958 “Famous Amos”] Korina with me and just the ‘67 pinged harder, and it was a little harder to play, too. But for Lazy Poker Blues, that’s the ’59 sunburst Les Paul. Done Got Over It, that’s the ’59 sunburst Les Paul. Twenty-Four Hour Blues, that’s a 1961 ES-355 mono, so it’s basically a 335 but with 355 appointments, no Varitone, and not stereo.”

Were there any wildcard songs, just “out there” ideas that made the cut?

“Josh brought an original song that I thought was really good, and we cut it [for] the end of the record, a song called Is It Safe to Go Home. I think it’s one of the stars of the record.”

Were there any covers that were out of left field?

“We pretty much curated everything, you know? We sifted through a bunch of songs and just like, ‘Hey, can I pull this off?’ But the other thing is, does it need to be done? There are so many covers records now, full of songs that are well-worn paths. I don’t need to add to the noise, you know what I mean? I’d rather pick songs that are killer or that mean something to us.”

- Blues Deluxe Vol. 2 is out now via J&R Adventures.

Jim Beaugez has written about music for Rolling Stone, Smithsonian, Guitar World, Guitar Player and many other publications. He created My Life in Five Riffs, a multimedia documentary series for Guitar Player that traces contemporary artists back to their sources of inspiration, and previously spent a decade in the musical instruments industry.

“It was tour, tour, tour. I had this moment where I was like, ‘What do I even want out of music?’”: Yvette Young’s fretboard wizardry was a wake-up call for modern guitar playing – but with her latest pivot, she’s making music to help emo kids go to sleep

“There are people who think it makes a big difference to the sound. Stevie always sounded the same whether it was rosewood or maple”: Jimmie Vaughan says your fretboard choice doesn’t matter – and SRV is his proof

![John Mayer and Bob Weir [left] of Dead & Company photographed against a grey background. Mayer wears a blue overshirt and has his signature Silver Sky on his shoulder. Weir wears grey and a bolo tie.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/C6niSAybzVCHoYcpJ8ZZgE.jpg)

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)