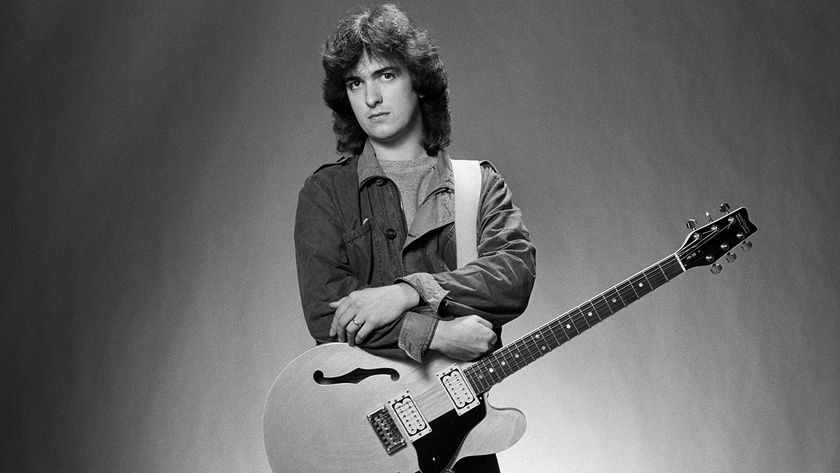

Jimmie Vaughan: Powerful Stuff

Originally published in Guitar World, July 2010

As he releases his first new album in nine years, Jimmie Vaughan celebrates the music he loves and remembers the brother he lost 20 years ago.

It's been nine years since Jimmie Vaughan released his last album, 2001’s Do You Get the Blues? But when it came time to record his new Plays Blues, Ballads and Favorites, Vaughan, who produced the album himself, didn’t have to think long about the sound he wanted to create with it.

“I wanted the dirt and the fun to be there, because that’s what made me fall in love with music when I was a teenager,” Vaughan says. “The audiophile freaks may hate this, because it sounds like a jukebox—it’s all raw, made with tube and tape, and nothing’s pristine. I’m just trying to capture what I hear in my head. That’s all I’ve ever tried to do.”

That’s a significant statement, considering that Vaughan has spent the past four decades playing and keeping alive the raw and authentic blues-rock that is a signature of the Austin, Texas, scene. Many people credit Vaughan’s younger brother, the late Stevie Ray, with helping that city become known far and wide as the southwest’s premier electric blues town. But it was Jimmie who helped advance Austin’s musical culture in the Seventies and Eighties as a member of the critically acclaimed Fabulous Thunderbirds. And it was Jimmie who inspired Stevie to try his hand at the guitar.

Jimmie always gave his little brother a lot to look up to. At 16, the elder Vaughan was flashing his chops in Dallas’ most popular band, the Chessmen, featuring drummer Doyle Bramhall. They even opened for Jimi Hendrix, who must have been surprised to see a white Texan teen copping his licks note for note. Of course, that’s nothing compared to what blues titan Freddie King would have thought if he ever stumbled on the kid who played around town billed as “Freddie King Jr.” “I could play all his songs,” Jimmie once recalled. “But I couldn’t sing any of them.”

Getting ever deeper into the blues, Jimmie moved to Austin with his band Texas Storm in 1969, and helped to kick-start a vibrant scene there. When Stevie arrived to become Jimmie’s bassist, no one could have predicted that he would eventually be the guy to make the world take notice of what was going on in this Texas college town.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Jimmie’s Fabulous Thunderbirds became the bedrock of Austin’s blues world, serving as the house band for the great club Antone’s. After sharing the stage with countless blues greats, including Muddy Waters, Buddy Guy and the three Kings of the blues, Freddie, Albert and B.B., Jimmie and the T-Birds seemed destined to be Austin’s first great blues export. But Stevie broke big first with his 1983 debut, Texas Flood. Ironically, his success paved the way for the T-Birds’ breakthrough hit, 1986’s “Tuff Enough.” Two years later, the band achieved mainstream success when its song “Powerful Stuff” was featured on the multi-Platinum soundtrack to the film Cocktail.

After leaving the T-Birds in 1989, Jimmie had one piece of unfinished business before launching a solo career: recording a long-anticipated album with Stevie. The brothers cut Family Style in 1990. The release should have been a triumph, but Stevie was killed two months beforehand, and the celebration became a memorial.

After taking a couple of years off, Jimmie finally made his solo debut with 1994’s Strange Pleasure. The album contained “Six Strings Down,” Jimmie’s acoustic lament for his brother, but the overriding theme was triumph over grief. It made a strong statement about the need to pick yourself up and keep moving after disaster strikes. “We all have to do that every day,” Vaughan says. “We don’t go the other way, because we just can’t.”

Sixteen years after its release, Strange Pleasure stands up as a modern blues masterpiece. The strength of the album’s songwriting was highlighted when classic rock hit machine Steve Miller covered three of its songs on Bingo!, his new album and first studio recording in 17 years.

On Plays Blues, Ballads and Favorites, Vaughan turned to some of his favorite blues and R&B songs from a lifetime of musical devotion. “It’s almost harder to do other people’s songs, because you’re setting yourself up to feel like you’re failing after years of hearing something as an ideal,” he says. “You can’t nail it as well as they did, and I hold myself to a high standard. But I tried to just have fun playing music I love.”

GUITAR WORLD You started out as a young buck of the blues, learning from the masters. Now you are one of the real-deal oldschool cats. Was that a natural evolution or a freaky occurrence?

JIMMIE VAUGHAN It’s so scary that I can’t even think about it. [laughs] I’m just doing what I love, and in a lot of ways I feel like I just got here. When I was a kid I said, “I want to be a blues guitarist when I grow up.” It was a total fantasy, and I’m still trying to do that.

GW So you don’t feel like you’ve nailed that down yet?

VAUGHAN You can’t ever quite be satisfied with something like that. I was always fascinated listening to guys like Albert Collins, Freddie King and B.B. King and thinking, How in the world do they know what they are going to play? I’ve been on a lifelong quest to figure that out, and all I can say to this day is that it’s all about feeling.

As a soloist, it all comes down to, “When they open that gate, what are you going to say?” After all these years, I still don’t always know the answer, and that gives me the feeling that it all could blow up anytime I’m onstage.

GW Come on, that’s not true.

VAUGHAN [laughs] I’m just telling you how it feels. Every time I go out there, I get excited and my hackles go up, and I jump out and it’s fun. I still love getting myself in the right frame of mind to go play, and I still love the sense of not knowing what’s going to happen. Every night is different. You can do all the right things all day and have a scary show, or you can stumble in, doing all the wrong things, and have a great gig. There’s no guarantee. And you’re on your own up there. It’s just a great, fun thing to do.

GW So it still feels exciting?

VAUGHAN Always! I play all day, every day. I just never stop playing, because that’s what I love to do. Basically, I’m living the dream, so I have nothing to complain about. Not only do I get to play music all the time but I also get to do it just the way I want. I like the niche I’ve found, and I’m just trying to play what I hear in my head, not be the most amazing guitarist in the world. For me, music is all about the space, the phrasing and how everything flows. I like stuff that feels like someone is talking to me, and that’s what I try to do—just express myself with phrasing and emotion.

GW What have you learned after so many years of studying the blues greats?

VAUGHAN When it’s time to solo, they hit it hard. They come out of the chute and play something so great that they could stop after a few notes and it would be the coolest thing you’ve ever heard. And they got that from the sax players I love, like Gene Ammons. The whole Texas single-note guitar school, starting with T-Bone Walker and Gatemouth Brown, which I am part of, was inspired by sax lines and the way that amplifiers first allowed guitars to come out of the rhythm section.

The best way I can think about it is, it’s like talking; you want to hear someone tell a really good story in his own voice. You can’t figure it out like a math problem, because you have to call on your feelings. It’s really hard to talk about an approach to soloing in a way that makes sense. It’s not like I intellectualize it. I’ve talked it about more right now than I have consciously thought about it in the last three or four years. Because for me it’s very physical and emotional.

GW It’s been 20 years since Stevie’s death. Has your view of his musical legacy changed?

VAUGHAN Well, no. I’m always amazed about the stories I hear from people all over the world, about the reach he had and the impact his music had on people’s lives. I’m happy and proud about that, but it’s hard for me to put his legacy in any kind of perspective.

I started playing before he did. I showed him how to play, and then he went off and did his thing, and…well, I’m still here. So I don’t think about his playing; I think about mine. He was my little brother. It’s hard to separate that fact from talking about his “legacy” or to even to separate him from me. Do you understand? You’re asking about his playing, his music, his legacy, but he’s my brother.

I know that he has a huge following and his music still impacts people. When he was here, it was incredible, but I was here too, and… [pauses]

GW I can hear how difficult this is to talk about. Is it easier to process and deal with after 20 years?

VAUGHAN No, it’s not. It really and truly is not.

GW A lot of your music expresses a deep joy at just being alive, which I especially hear on Strange Pleasure, which you recorded four years after Stevie’s death. To me, that was a message about how to continue on after tragedy and despair, and it projects a strong message without ever saying it.

VAUGHAN Thanks. This stuff is real emotional to me. It’s very real. A lot of people don’t get it, so I guess it’s not for everyone, but I’m glad that some people hear all that, because that means some of the emotions and thoughts I am trying to project get through.

There are only two kinds of music: the kind you like and the kind you don’t. You can do anything with music and shouldn’t think about it in terms of genres or rules. Within music, there is total liberty. No one can make you like something or play something, and no one can take it from you—not the government, nobody. That’s what makes music so great. It encompasses everything.

GW Are you still playing stock Jimmie Vaughan Tex-Mex Strats? And what are you running through?

VAUGHAN Yes. I’m still playing some of the first ones that they gave me. I tweak them up the way I like them, because I like to tinker, but I also play them right out of the box. I’ve also been playing a Fender Coronado with DeArmond pickups, which is a real oddball and a lot of fun.

I played Matchless for many years and still love them, but Fender has out a new Bassman reissue with a lacquered tweed finish [’59 Bassman LTD] that just sounds great right off the shelf. On the album, I used one of those and a 4x10 Matchless, and that’s it.

I really don’t use any effects, except for an occasional tremolo. I’ve always felt like the Stratocaster itself is a gadget that can give you an awfully wide range of sounds.

GW Are you still open to changing your guitar approach?

VAUGHAN My guitar playing is constantly in a state of change. That’s the fun of the whole thing. Every song is an excuse for me to play lead, a blank canvas for me to paint on, and I don’t want them to be the same. I’m still learning all the time. In fact, I still take music lessons.

GW What do you study?

VAUGHAN Theory, music knowledge… I work on all the basic stuff with a music teacher. I’m just constantly in a state of pushing it and exploring, because that’s what I love doing.

GW So you don’t subscribe to the belief that “book learning” can kill the feel?

VAUGHAN No. I don’t think you lose anything; you just add. Just because I learn a scale or some new changes doesn’t mean I’m going to use it. But if the right situation comes up, I’ve got it in my trick bag. I still play my blues, but I enjoy all music. I really have the best job in the world, because I do what I love, and that’s what I’ve always done.

GW You’ve talked in the past about how hard it was to play sober after years of drinking. Does that struggle fade away after doing it for so long?

VAUGHAN It gets easier and more comfortable all the time, but it never goes away. You just stay with it, and the older you get, the more comfortable you get and the more confident you are that you simply can do it. That excuse goes away. That’s not to say you don’t have problems anymore, but you have a different way of dealing with it, and that makes it easier.

“The concept of the guitar duel at the end was just appalling”: Crossroads is an essential piece of '80s guitar lore, but not every guitar legend was a fan of the film

“Zal is really nobody’s guitar hero. Fans say he’s the most underrated player ever; many guitarists rate him amongst the best... but I’ve never heard anyone call him their ‘guitar hero’”: Billy Rankin on lessons learned from the legendary Zal Cleminson