Jethro Tull: Tull Tales

Originally published in Guitar World, September 1999

An album-by-album look at classic Jethro Tull.

Long before Austin Powers made “shag” part of the popular vernacular, another quintessential Brit with a tweedy accent was introducing America to the quirky side of English culture. Like Powers, his clothes came from another era, and his sense of social conventions seemed to have been frozen in time. He was even known to make frequent references to “wood.”

It’s been years since Ian Anderson has had anything approaching Powers-like stardom in America. But back in the early Seventies, as the soul, wit and flute-wielding/acoustic guitar-plucking madman behind prog-rockers Jethro Tull, Anderson helped to herald an age of musical theatrics and experimental excesses on landmark albums like Stand Up, Aqualung and Thick As a Brick—just three of the 20-plus original studio albums Jethro Tull has released in its 32-year history.

Now Tull, a band that never really went away, is back once again with a new album by the cyberspace-savvy name of jtull.com (label??) and a summer tour that has the group running across Europe and into America at the end of August. It’s a grueling schedule of recording and touring that the band has followed nearly every year since its inception. But it’s exactly this routine which has, as Anderson puts it, “helped Tull to survive almost in spite of itself.”

“We’ve never been a hit band that appeared regularly on television or in the pop charts,” he explains over a cup of coffee near his home in the southwest of England. “We don’t have record sales that are driven by singles, by radio play, by MTV videos or whatever. In fact, most of our 50 million or so album sales have occurred in dribs and drabs over a long period of time and in a lot of countries all over the world.”

What Tull does have is a strong and loyal fanbase that helps the group survive against the odds. Says Anderson, “This kind of operation is based on the commitment and loyalty of the fans, not necessarily how good or bad your latest record or even your latest tour might be. Because they will forgive you a lot.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Jethro Tull has needed a pardon on more than one occasion. Back in 1973, for example, when the group reached for the limits of excess with the critically reviled, album-length Passion Play. And again, amid the punk boom of 1976, when, having given the world such early Seventies musical treasures as “Aqualung,” “Locomotive Breath,” “Bungle in the Jungle” and “Living in the Past,” Tull embarked upon the ill-conceived rock opera Too Old to Rock and Roll: Too Young to Die, an attempt, in Anderson’s words, to “reach a lot of younger kids again.”

But along with the bad, much good has come too. Aqualung and Thick As a Brick today rank among the best-selling and most-influential albums of the Seventies, while Stand Up (1969), Warchild (1974) and Songs from the Wood (1977) remain strong favorites among even casual fans of the group. Likewise Crest of a Knave, the 1987 Grammy Award winner which, coming after a long dry spell, helped Tull earn back some of its American following with radio-friendly tracks like “Steel Monkey,” “Farm on the Freeway” and “Jump Start.” In the past 30 years, few groups have demonstrated such resilience in the face of shifting musical trends.

As jtull.com demonstrates, Jethro Tull is still up to the job of being prog-rock’s most resourceful group. The new album evokes some of Tull’s heaviest and most adventurous work, with riff-oriented songs that hark back to Benefit, as well as straightforward rock songs that would have sounded right at home on Aqualung.

“There’s lot of elements within it that I imagine will make people say, ‘Ah, yeah, that’s the kind of Jethro Tull stuff we remember,’ ” says Anderson. “It’s a rock album for people in big-boy’s trousers.”

Having said that, Anderson is quick to add that the trousers come with a fashionably understated jacket. “The album doesn’t have loads of effects and complex stuff,” he says. “It’s pretty sparse-sounding, kind of stripped down to the essentials.”

“I think we’ve listened and learned from our last three albums,” offers Martin Barre, the group’s guitarist. Next to Anderson, Barre is the second longest-serving member of Tull, having joined the group in 1968, prior to the recording of its second album, Stand Up. “We’ve found that there have been very few tracks from those albums that played well live, and it’s so important to us that we have really strong material to play at gigs. So the new album is a lot more straight-ahead. There’s no going back to the odd time signatures. It’s always been fun for us to learn the complex arrangement of a complex piece of music. But the punters have got to understand it and enjoy it as well.”

For the most part, the “punters” have followed along quite well. They first got onboard back in 1967, when Britain’s blues boom was casting its shadow over the land. It was the year that Ian Anderson hooked up with guitarist Mick Abrahams, bassist Clive Bunker and drummer Glenn Cornick and became a sensation on the London blues scene practically overnight. Named for an 18th century agriculturist—certainly not the last time Ian Anderson would draw upon obscurity for influence—Jethro Tull soon became the resident band at London’s prestigious Marquee club, a gig that enabled them to record their first album, This Was. It was while recording the album that Anderson began to feel sharply the limitations which the blues genre placed on his creativity.

“Mick Abrahams was of the old rock and blues school in the U.K.,” says Anderson. “He was a respected guitar player who had a very defined style and he could play within it convincingly. But outside of that style, he was a no-hoper: he just couldn’t learn anything musically if it didn’t fall into the styles that he knew.”

In short order, Abrahams, a favorite with Tull’s early fans, was fired and Barre recruited in his place. A player of admittedly limited ability, Barre was eager for Anderson’s guidance; Anderson, for his part, was only too glad to offer it, directing the young guitarist away from familiar rock and blues rhythms toward complex arpeggiated patterns and unusual time signatures. With Barre holding down electric guitar duties, Anderson would add layers of rustic-sounding acoustic, mandolin, balalaika and—his famous mainstay—flute. The songs that resulted from this menagerie of instruments were unlike anything anyone had heard before. Among the influences of rock, jazz, folk and Eastern music, Anderson injected his songs with images of an England historically depicted in wood-cut images, complete with feasts and faires, beggars and dandies, minstrels and country squires. Jethro Tull had arrived.

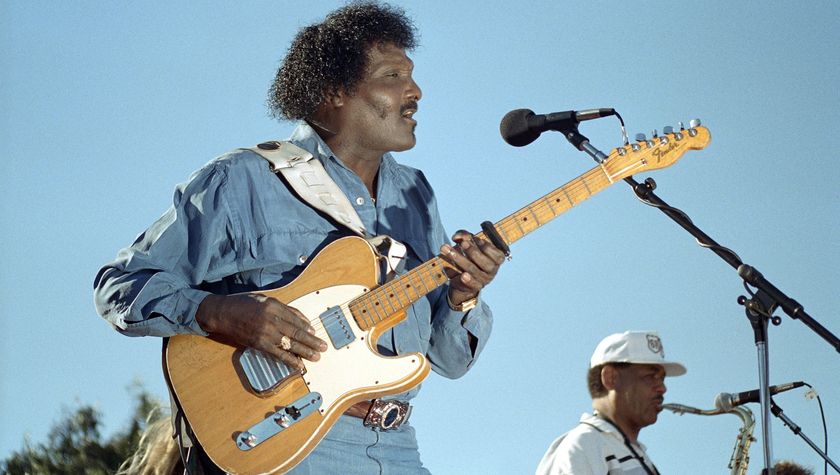

The group’s image was duly changed to suit the new music. Gone were the corduroy trousers and jean shirts; in were wardrobes of balloon-sleeve shirts, velvet pants and garish vests. Anderson cut the most memorable figure with his neo-Renaissance greatcoat, tights, codpiece and rustic leather boots that gave his slight frame a deceptively towering appearance. The crowning touch was “the stand”—Anderson’s distinctive manner of crooking up his right leg while playing the flute, so that he perched on the stage like a hairy, flightless bird.

Now in his fifties, Anderson can still get the old leg up, although his hair has receded and the shaggy wardrobe was retired around the time Sid Vicious made safety pins a facial accessory. These days, he cuts a more modest figure up on the stage. The music, however, remains as adventurous as ever.

“I keep creating partly for fear of boredom,” says Anderson. “I’m genuinely terrified of the idea that one day I won’t be doing this and I won’t be doing anything particularly interesting either.” And despite having written nearly all of the material on Tull’s albums and his three solo records (his third, The Secret Language of Birds, is due in February 2000), Anderson’s well of creativity is far from depleted. “I’m very motivated by the occasional creative payoff that comes when something goes really well, be it a song, a recording or performance,” he says. “The payoff is enormous—when you get it. Most of the time, though, I’m filled with self-loathing and general frustration at the limitations I have as a musician.”

In other words, the career musician’s life isn’t as pretty as it looks.

Says Anderson: “I don’t think successful musicians were really put on this planet in order to have a great time, pat themselves on the back and say, ‘Oh, what a clever boy I am!’ I think that, like most artists, we were put on the planet to suffer just a little. And we do.”

For all of its levity and wacky Briticisms, the music of Jethro Tull has inevitably dwelled on the dark side of human nature. It is the product of much soul searching on Anderson’s part as well as his reluctance to embrace the easy answers and hedonism of the status quo. Even in the early Seventies, when sex, drugs and rock and roll were the party platform adopted by virtually every rock band, Jethro Tull were the lone dissenters. “I wasn’t into the drug culture and party culture of the times,” says Anderson. “It always offended me that people assumed I was on amphetamines, or something.” His temperance earned him the wrath of at least one fellow musician. “We were Led Zeppelin’s support act on a rather lengthy arena tour. And although they were party animals and certainly lived life to the excess, we got on fine with them. But Robert Plant didn’t like the idea that I wasn’t playing the game. I suspect he found that irritating about me, and I think that’s part of the reason he and I never hit it off.”

Anderson’s sober attitude toward drugs extended to his political beliefs, and at a time when criticizing the status quo was de rigueur for rock stars, he stayed true to his conservative views. “There’s a line in ‘Living in the Past’ that caused a bit of a problem with some people,” he says. “It goes, ‘Now there’s revolution, but they don’t know why they’re fighting.’ That was one of the things that got me into trouble with people of my generation and with other musicians. No one likes folks who appear to be bucking the trend. So many musicians were politically and socially going down this prescribed track of appearing to have left-wing credentials, whilst at the same time raking in vast piles of money and living in big houses in Laurel Canyon. I found that a little odd.”

But Anderson was not so conservative when it came to criticizing two of England’s most established orders—the Church of England and Britain’s “stiff upper lip” propriety. Half of Aqualung is devoted to songs in which Anderson indulges his personal grudge against religious hypocrisy, while Thick As a Brick is a tirade against society’s tendency to encourage social decorum and financial success at the expense of personal expression and individuality.

Explains Anderson, “Most of what I’ve written songs about are things that come out of the confusing emotional, spiritual and psychological period of time when you’re going through puberty. All of that stuff is still fermenting like a very old wine. I can still uncork that bottle now when I’m writing a song and identify with that earlier version of me. That’s why I maintain that I feel very much the same person I was when I was 14 or 15 years old. I just really feel like I’m the same guy.”

With the eminent release of the group’s latest effort, Guitar World asked Anderson to spin us back down the years with a first-ever comprehensive overview of the group’s studio output. Never one to make light work of a daunting task, Anderson fulfilled our request with a vengeance, filling no less than three 60-minute tapes with his reminiscences before we finally, and with a deep sigh, punched the stop button. What follows is an excerpt of our afternoon spent living in the past.

This Was (Chrysalis, 1968)

“When we went in to make This Was, I felt okay that we were playing blues, but I also felt that we were just being somewhat imitative of other groups. By the time we finished the record, I was aware of the difficulties I would have working with Mick Abrahams, and not only because of his limited ability outside of playing blues guitar. He was content to play three or four nights a week in pubs, but the rest of us saw the record as a stepping stone to something bigger—as a chance to travel abroad and go to America. Mick didn’t want to work six or seven nights a week. He didn’t want to travel, and he refused to go on an airplane. We just had a huge logistical problem, as well as a musical problem that could only be resolved by finding somebody else. Mick left acrimoniously, and went on to form his own blues band, Blodwyn Pig. But we patched up soon after.

“One very good thing did come out of our association, however: I had been a guitar player since I was 16 or 17, and it was only when I met Mick that I quit playing guitar and started working on the flute. And obviously, the flute is the thing I’m best known for. I owe that to Mick.”

Stand Up (Chrysalis, 1969)

“This was Martin Barre’s first album with us, and it marks the turning point in our music, away from the blues and toward progressive rock. It is a very broad, eclectic album of progressive rock, and the end result is a set of songs that nobody else could have written. I was particularly pleased with the record, and still am, because nobody else was doing that then and the songs are very idiosyncratic in terms of their performance and writing. Looking back on it, it’s one of the records that I feel was a really important one. I’m glad it wasn’t the first album; I’m glad we had done something else first, just to cut our teeth on. But it was a very good second album to make.”

Benefit (Chrysalis, 1970)

“I guess you could say that this was our guitar riff album. It was done in a year when a lot of people were working with ‘the riff,’ an idea that had obviously come to prominence with bands like Cream, Hendrix and Led Zeppelin. Since that style of guitar playing is very electric, there is very little acoustic guitar on Benefit. It’s a rather dark and stark album, and although it has a few songs on it that are rather okay— ‘To Cry You a Song’ and ‘Sossity, You’re a Woman’—I don’t think it has the breadth, variety or detail that Stand Up has. But it was an evolution in terms of the band playing as a band. It also marked the point where John Evans came into the band to play piano and organ, so it was in a way a natural part of the group’s evolution.”

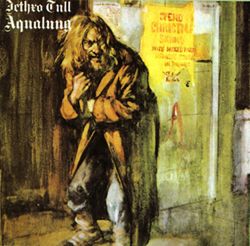

Aqualung (Chrysalis, 1971)

“Aqualung marks the point at which I had the confidence as a songwriter and as a guitar player to actually pick up and play the guitar and be at the forefront of the band. It’s also the album on which I began to address religious issues in my music, and I think that happened simply because the time was right for it. Addressing religious issues in simplistic pop-rock terms was permissible then. I’d have to disguise some of those sentiments to make it pass muster today.

“Aqualung wasn’t a concept album, although a lot of people thought so. The idea came about from a photograph my wife at the time took of a tramp in London. I had feelings of guilt about the homeless, as well as fear and insecurity with people like that who seem a little scary. And I suppose all of that was combined with a slightly romanticized picture of the person who is homeless but yet a free spirit, who either won’t or can’t join in society’s proscribed formats.

“So from that photograph and those sentiments, I began writing the words to ‘Aqualung.’ I can remember sitting in a hotel room in L.A., working out the chord structure for the verses. It’s quite a tortured tangle of chords, but it was meant to really drag you here and there and then set you down into the more gentle acoustic section of the song.

“With ‘Locomotive Breath,’ I knew I wanted a song about a runaway train, where things are going out of control and you can’t get off the train. It’s safe to say that kind of situation mirrored an aspect of the band’s life at the time, what with all the touring we were doing. We actually had to record Aqualung in a rather short time between tours, so it was done very quickly. Island Studios had just opened up, and it was a shakedown period for the studio; there were a lot of technical problems. Adding to them, the band was having problems recording ‘Locomotive Breath.’ We just couldn’t get the feeling, and I was failing to convey to the band what the song was about and how it should work. So I went out and played high-hat and bass drum for four minutes to lay down a rhythm track; this was in the days before drum machines and sequencers. Then I played an acoustic guitar part and some electric guitar parts, and then we tacked on John Evans’ piano intro at the front of it, and the others overdubbed their parts onto mine. So nobody actually played on that track at the same time, but it’s not a bad performance whatsoever. That was the only time we ever did anything like that back then.”

Thick As a Brick (Chrysalis, 1972)

“Since people thought Aqualung was a concept album, we decided to give them one. Thick As a Brick was tongue in cheek, what with the album’s pretense that the lyrics had been written by a 12-year-old school boy named Gerald Bostock. Monty Python had just come to prominence, and people were in tune with that slightly surreal type of British humor. And at the same time, the album expressed some serious sentiments about English society, as well as some rather serious music writing. But it was also meant to be a bit of fun.

“The phrase ‘thick as a brick’ is a North English colloquial term meaning ‘stupid.’ Like the religious themes on Aqualung, the theme of Thick As a Brick came out of my adolescent feelings about society and how it tries to bend you away from your will and toward its will, as if you’re not bright enough to make your own choices. I wasn’t a precocious child, but I knew how it felt to be one of the more academically gifted people; I knew what it felt like to be ostracized, despised and feared by the rank and file, who weren’t terribly bright. Nobody likes the clever kids. So the album came to represent the gulf between growing up clever and the social discrepancy that results from that: the fact that you were really disliked by some of the kids.

“While writing the album, I’d get up every morning and compose a little something, then take it to the band later that morning for rehearsal. We’d work out the parts and perhaps advance the song toward the next stage of its development. We did two weeks of solid rehearsal and then recorded it in about 10 days. Some linking sections were created in the studio, but the blood and guts had been worked out well in advance. It wasn’t a difficult album to make, because all of the material was there and we just had to get it on tape.”

Living in the Past (Chrysalis, 1972)

“Living in the Past was simply an attempt to compile our singles into one album. We had released a number of singles up to this point—‘Living in the Past,’ ‘Teacher,’ ‘Witches Promise’—and they were all contrived for a very specific reason. A lot of English bands had been criticized for becoming successful in the U.K. and then going off to the U.S. and abandoning their English fans. Once we started touring in the U.S.A., we used the singles as a way of keeping the water warm back in the U.K., so as not to risk losing our audience there.

“The singles were never songs that were leftover from album sessions; in fact, they were completely divorced from the album recording process. ‘Living in the Past’ was written and recorded during our first U.S. tour, in ’69. It was written in Boston, the backing track was recorded in New York and the vocals in San Francisco or Los Angeles. It was mixed and the tape sent back to the U.K. It was released [in the U.K.] while we were on tour.”

A Passion Play (Chrysalis, 1973)

“With Thick As a Brick, we took the idea of the concept album and had some fun with it. Now we thought it was time to do something a bit more serious and make an album that wasn’t a spoof and wasn’t meant to be fun. We ended up going to record the album at Chateau D’Herouville in France, where people like Elton John and Cat Stevens had made records. Our original plan was not to make another concept album. The project started off as a collection of songs, including two that ended up going onto our next album, War Child: ‘Bungle in the Jungle’ and ‘Skating Away (On the Thin Ice of a New Day).’ A certain theme had begun to emerge among the songs—how the animal life is mirrored in the dog-eat-dog world of human society—but the project just wasn’t working out. So we abandoned what we’d done and went back to England. [Material from these sessions was collected in the double-CD Nightcap (Chrysalis, 1995)—GW Ed.]

“Back home, I ended up almost completely rewriting all of the material we’d worked on in France, and this became A Passion Play. The concept grew out of wondering about the possible choices one might face after death. It was a dark album, just as we had intended, but it was missing some of the fun and variety that was in Thick As a Brick. The critics savaged us. Chris Wells of Melody Maker and Bob Hillburn at the Los Angeles Times wrote really negative reviews that everybody jumped on and reprinted or based their own reviews on. It really snowballed from there, and we got a fair old pasting for that one. On reflection, the album is a bit one-dimensional; it’s certainly not one of my favorites, although it has become something of a cult album with some fans.”

War Child (Chrysalis, 1974)

“ ‘Bungle in the Jungle,’ which is perhaps the best-known track off War Child, was the key track for the aborted project we began in France. It’s a rather odd song for Jethro Tull, I think. Every so often there are those songs that fall into the conventional pop-rock structure—songs like ‘Teacher,’ for instance— but that style isn’t our forte. We’re not very good at it because I’m not that kind of a singer, and it doesn’t come easy to me to do that stuff. But ‘Bungle’ one of those songs that was nice to have done. It’s got the Jethro Tull ingredients, but it’s a little more straight-ahead. It’s Jethro Tull in tight leather trousers.”

Minstrel in the Gallery (Chrysalis, 1975)

“Minstrel is one of two albums that were made during the year we recorded abroad to avoid the U.K.’s exorbitant tax rate on performing artists. Both Minstrel and its follow-up, Too Old to Rock and Roll, were made in Monte Carlo and in the same year, although they were released in different years. Minstrel is actually a reflective album, because a lot of the music for it was written at a time when I was looking back with some nostalgia on my life in the U.K. I’d always lived there, and suddenly I was out for a year. So a lot of the songs— like ‘Baker Street Mews’ and the title track—are reflective of London city life. The music also reflects my life as a musician since at that time I was not in a permanent relationship and living out of a suitcase, in hotel rooms and rented apartments.”

Too Old to Rock and Roll: Too Young to Die (Chrysalis, 1976)

“When Jethro Tull started out, during the blues boom, we were turning our backs on all the things that had to do with commercial pop success; we were the punks of our generation. Six or seven years later, there was a full turnaround again, when the punk movement in the U.K. turned its back on all the progressive rock and arty music and got back to the basics of aggressive, simplistic, nihilistic music.

“That theme became the subject matter of Too Old to Rock and Roll. The album presents an aging rock and roll rebel who finds his career being undone by the latest breed of rock musician. It was not directly a response to punk, but it was certainly influenced by this very cyclic nature of pop music.

“Perhaps understandably, some members of the press took the album as our attempt to ‘get with’ the punks. But in fact we were really trying to point out that this business is cyclic, and that if you stick around long enough, you do come into fashion again.”

Songs from the Wood (Chrysalis, 1977) and Heavy Horses (Chrysalis, 1978)

“After Too Old to Rock and Roll, we returned to England, and I settled down, got married and bought a home. It gave me an opportunity to evaluate and reflect upon the cultural and historical significance of making that commitment to English residency, not only as a taxpayer but in the spiritual sense of saying, ‘This is where I’m going to live.’

“Our next two albums, Songs from the Wood and Heavy Horses, reflect that change in environment and change in mindset. As a result, a lot of things that went into those two albums have to do with British folklore and mythology. Songs from the Wood, in particular, is an album that, for all the band members, was a reaffirmation of our Britishness. Heavy Horses was a somewhat darker, heavier album, but essentially it came from the same spirit and explored rather similar themes.

“These two albums represent one of the several times in Jethro Tull’s lengthy discography that the same idea followed from one album to the next. Stand Up is sort of an ‘up’ album, followed by Benefit, which is sort of a ‘down,’ dark album. Likewise with Thick As a Brick and Passion Play. When you’re making an album every year, I think you do tend to oscillate between having feelings of cheerfulness followed by feelings of introspection. I think that’s true of those two albums, and they do hang together as a pair.”

Stormwatch (Chrysalis, 1979)

“We closed the Seventies with this album, and it is a rather dark album, with gloomy themes about the environment. The mood of the late Seventies was that, even if the Russians don’t get us, the upper atmosphere will. I played about half the instruments on the album because [bassist] John Alcock was too ill to play at that time.”

A (Chrysalis, 1980)

“A started life as a solo album. I just wanted to take a break from the band and do something different, and I wanted to see if working with other people might make the music take on a different sound or feel. [Former Roxy Music keyboardist] Eddie Jobson had supported us on a few U.S. tours, and he came onboard and brought along his drummer, Mark Craney. I set about principally with the idea of working with just Eddie and Mark, but then I asked Martin to come along to do a bit of work on it, and he just ended up staying on. Dave Pegg, from Fairport Convention, had just joined Jethro Tull, and I figured since he had never played on a Jethro Tull album, it was okay to ask him to play on this record.

“At the time that we finished the album, our former manager, Terry Ellis, persuaded me that this should be a Jethro Tull album because I had Martin on it, and because he thought a solo album should just be me plunking on a guitar. So I let myself be persuaded. Unfortunately, statements were put out to the press before I could discuss the matter with the band. Suddenly, everyone in Jethro Tull outside of Martin and Dave Pegg thought they’d been sacked and replaced with Eddie and Mark. Our drummer, Barrie Barlow, had left the band to take some time off after Stormwatch. It was just a temporary thing, but I think after it was announced that A would be a Jethro Tull album, he just had a bad feeling about things and that temporary split became a permanent split. So it was not a nice thing.”

Broadsword & the Beast (Chrysalis, 1982)

“This album came out at a difficult time for us. It was our first album in two years. Chrysalis Records had brought in an American rock and roll producer they thought we should work with—his name escapes me now. He just wanted to get the songs on tape as quickly as possible and then mix it back in America, where we weren’t around. After the second week of working with him, we said to the record company, ‘Get this guy out of here.’

“It was just before Christmas, and we were stuck without a producer. So we got out the Yellow Pages and we looked up ‘record producers.’ Which sounds ridiculous, but it’s absolutely true. And we went down the list, and the first name we recognized was Paul Samwell Smith, who had worked with Cat Stevens and was, of course, an original member of the Yardbirds.

“Paul came down that night and we started work. And he was great, because he was a really objective guy to have in the studio. At that time I was planning to build my own home studio, and Paul could kind of nursemaid everyone through their parts on the record while I looked over brochures of mixers and made plans for my home studio. He really helped out a time when I wasn’t personally looking for the stress and strain of having to produce, write, engineer and mix and all the stuff that I do.”

Under Wraps (Chrysalis, 1984)

“Under Wraps was the first album we made in my home studio. When we made the album, we set about trying to combine the benefits of music that originated from what was then new sampling technology with our traditional band approach. It was an unusual combination of musical sounds, some of which were cold and calculating and others that were more evocative. I enjoyed the album because, as a vocalist, I really stretched myself to the limit doing that album, in terms of its range and the structure of the melodies. But, of course, that album became my undoing when it came time to perform it live. I seriously damaged my voice later in 1984 when we toured and I had to sing all of that material every night. My voice has never really quite recovered.”

Crest of a Knave (Chrysalis, 1987)

“This, of course, had been our biggest success in America for quite some time. It won the Grammy [Best Heavy Metal/Rock Album], but that was sort of incidental to everything. I just think we had an album that was commercially uplifting because it had three radio-friendly tracks. So we found ourselves back in favor again, with more ready acceptance at radio, first with ‘Steel Monkey,’ then with ‘Farm on the Freeway’ and ‘Jump Start.’

“We worked with sampling technology again for Crest of a Knave. ‘Steel Monkey’ was based around a sequencer riff, and it didn’t have any flute in it. So it was yet another atypical Jethro Tull song that was a radio hit. By comparison, both ‘Farm on the Freeway’ and ‘Budapest’ are very typical Tull songs. ‘Budapest’ is the kind of song I like to write because it embodies a lot of different nuances which I think are subtly joined together. It sort of moves from classical to slightly bluesy to folk, and it just slips between them and you don’t see the stitching. The song is like a really good Elton John hair piece: you can’t see the joints too obviously.”

- Rock Island

- (Chrysalis, 1988)

- “This was another instance in which we released a dark album after a bright-sounding, upbeat album. Rock Island didn’t produce a lot of classic-sounding Jethro Tull songs, but it does have a lot of idiosyncratic Jethro Tull-sounding songs. It’s just a more somber album, and I guess you have to be in the right mood to listen to it. Like if your granny’s just died or the dog got run over, you might put that album on to make you feel even worse.”

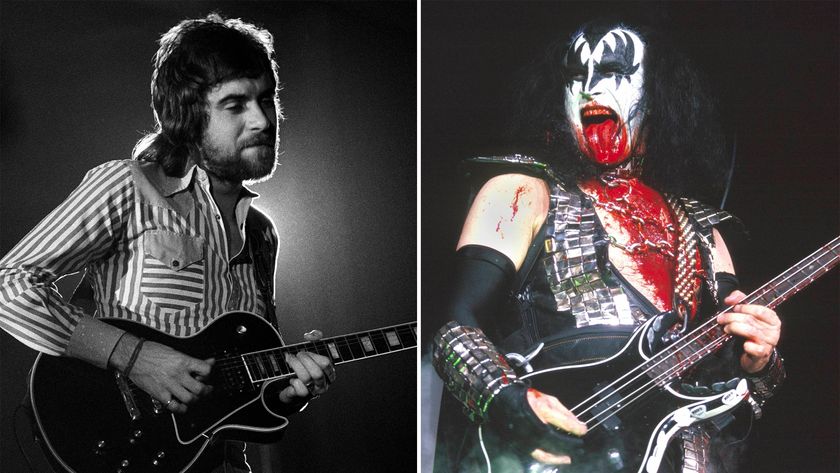

“I had to use the same microphone that Gene Simmons used with all the blood coming out of his mouth. Can you imagine that!”: Mick Rogers recalls Kiss supporting Manfred Mann's Earth Band in their early days

“Once Dave got his Roland Space Echo, it changed the vibe… that, and a lot of marijuana”: They inspired everyone from Oasis to the Smashing Pumpkins. Now English post-punk luminaries the Chameleons are back for more

![[L-R] George Harrison, Aashish Khan and John Barham collaborate in the studio](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/VANJajEM56nLiJATg4P5Po-840-80.jpg)