“At that tempo it was like playing a brand-new song. I had to watch Bernard Purdie’s foot!” How Jerry Jemmott stayed on top of Aretha Franklin’s Respect – and recovered from his mistakes – at the Fillmore West in 1971

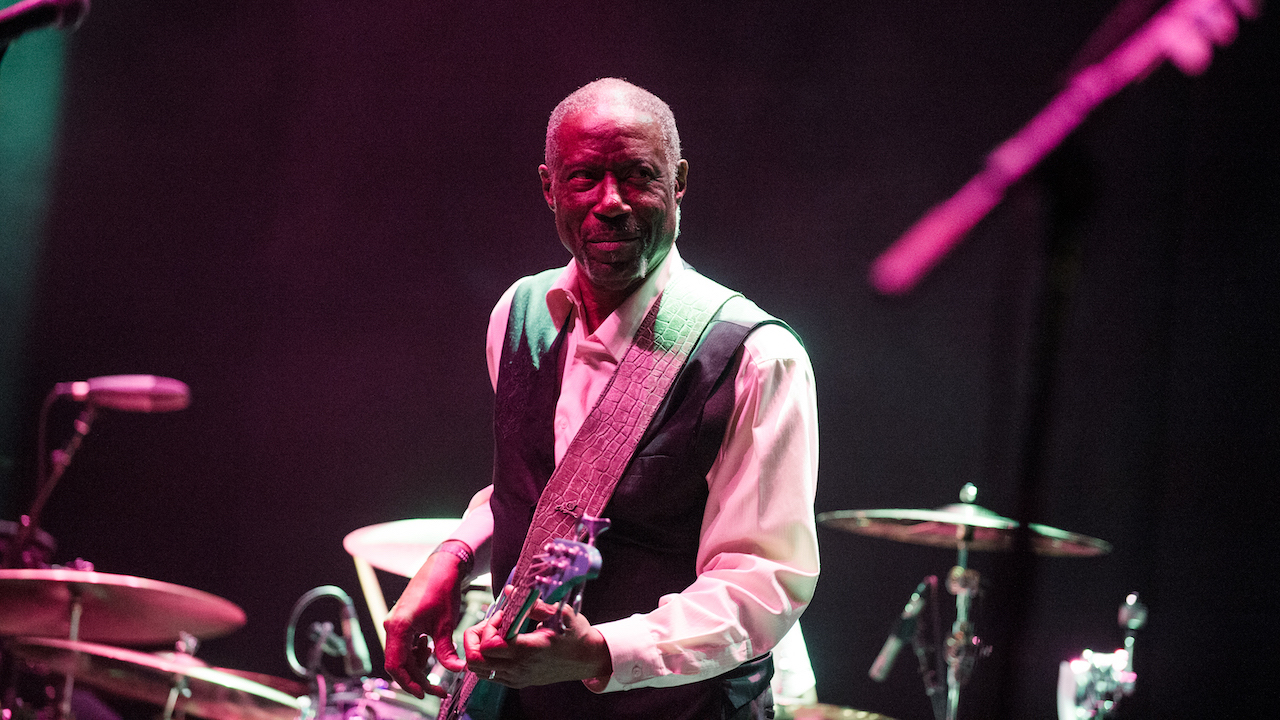

Jerry Jemmott plucked his sunburst ’65 Jazz Bass in front of his Acoustic 360 rig

In R&B, it’s a time-tested tradition as old as spin moves and shiny suits: An artist records a hit song and immediately plays it at a brighter tempo live. And so it was with Aretha Franklin's Respect, from her desert-island disc Live at Fillmore West, recorded in San Francisco in early March 1971.

“In addition to us playing all the songs faster, Respect was counted off fast,” said Jerry Jemmott, who sat in the bass chair plucking his sunburst '65 Jazz Bass in front of his Acoustic 360 rig. “It was the opener, and King Curtis and Aretha wanted to get the excitement going. There's a version from Montreux that was up near 200 BPM; I had to watch Bernard Purdie's foot!”

As a result of the pumped-up pace, Jemmot's Fillmore bassline is equal part instinct, experience, creativity, pure groove, and “just trying to hang on!”

Although Aretha Franklin was surrounded by a Curtis-collected all-star band that included Jemmott, drummer Bernard Purdie, guitarist Cornell Dupree, organist Billy Preston, the Memphis Horns, and guest Ray Charles, live is still live. Thus, when the announcer introduced Franklin, the crowd let out a roar that caused Jemmott to miss Purdie's stick count-off and the first bar.

He recovers in time for bar 2 – but in bar 7, believing Franklin is about to sing the verse, he plays a G before quickly getting back to C on beat two. In one last unsure live moment, when Franklin unexpectedly starts verse one in bar 11, Jemmott plays a C before instantly adjusting to G on beat two.

Blips aside, speaking to Bass Player in 2011, Jemmott recalled his inspiration for the part: “It was the combination of knowing what Duck Dunn played on the original Otis Redding version, and what Tommy Cogbill played on Aretha's studio version, along with my bassline on Aretha's Think, which was permeating all of my parts back then. But at that tempo it was also like playing a brand-new song.”

Two key Jemmott principles come into play in the opening measures. One is his Think-like pivot on the root and 5th, with ghost-notes and pickups added to funk things up in between the I and IV chords. “Think really came from country music. I always liked the simplicity and solid footing of country basslines.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The other concept is his creation of a two-bar phrase for both verses and choruses, in which the first measure sticks to the root-and-5th rhythmic side, while the second adds melodic motion (the walk-up to the C first heard in bar 2). “I call it harmonic propulsion,” noted Jemmott. Bars 6 and 8 typify this usage of chromatic passing tones – part of his uptown New York jazz background.

The first chorus reveals another key to the part: Jemmott's use of open D and A strings to pivot off. “I was not the more studied person I am now, so some of those G's might be open strings instead of 5th-fret D string. The melodic idea in the second verse came to me spontaneously, but I later realized that's something Duck played on Otis's version.”

The bridge is marked by a slightly straighter feel, with no 16th motion and mostly roots and 5ths. “I always like to change up in the bridge to distinguish it as something different. Here, I wanted to give the part a chance to breathe, so for me the line almost functions like a pedal point.”

In the fourth verse and chorus, Jemmott employs subtle theme development to keep his part evolving: specifically, his restatement of the Duck Dunn idea, but this time over the V chord as well as the IV chord.

The final chorus inspires more subtle development. This includes Jemmott's initial use of an open E, and his use of a low F for the first time. He also alters the rhythm of the IV-chord measures nicely. The band shows its dynamic savvy by collectively dropping the volume while still percolating.

Jemmott has one final move heading into the last stretch: he applies his harmonic propulsion by adding a walk-up in the C7 measures. This effectively changes what was a two-bar phrase to a one-bar phrase, doubling the intensity with gospel-like grandeur.

Jemmott advised that before you attempt to play the song, first listen to the track to get the vibe and scope out any tricky measures.

“Ultimately, the part is about supporting, reacting to, and pushing Aretha. It was a tremendous thrill to play with two giant talents at once in Aretha and King Curtis on that tour. In addition to the unbelievable energy, it was very spiritual-like going through a baptism every night!”

Chris Jisi was Contributing Editor, Senior Contributing Editor, and Editor In Chief on Bass Player 1989-2018. He is the author of Brave New Bass, a compilation of interviews with bass players like Marcus Miller, Flea, Will Lee, Tony Levin, Jeff Berlin, Les Claypool and more, and The Fretless Bass, with insight from over 25 masters including Tony Levin, Marcus Miller, Gary Willis, Richard Bona, Jimmy Haslip, and Percy Jones.