Jeff Beck – the lost interview: “There are many guitarists who can play like a typewriter. Technically they’re great, but that’s not my style”

In this interview from 1999, Jeff Beck talks candidly of how it might all end before staring a career downturn in the face and getting back on the horse with the spectacular Who Else!

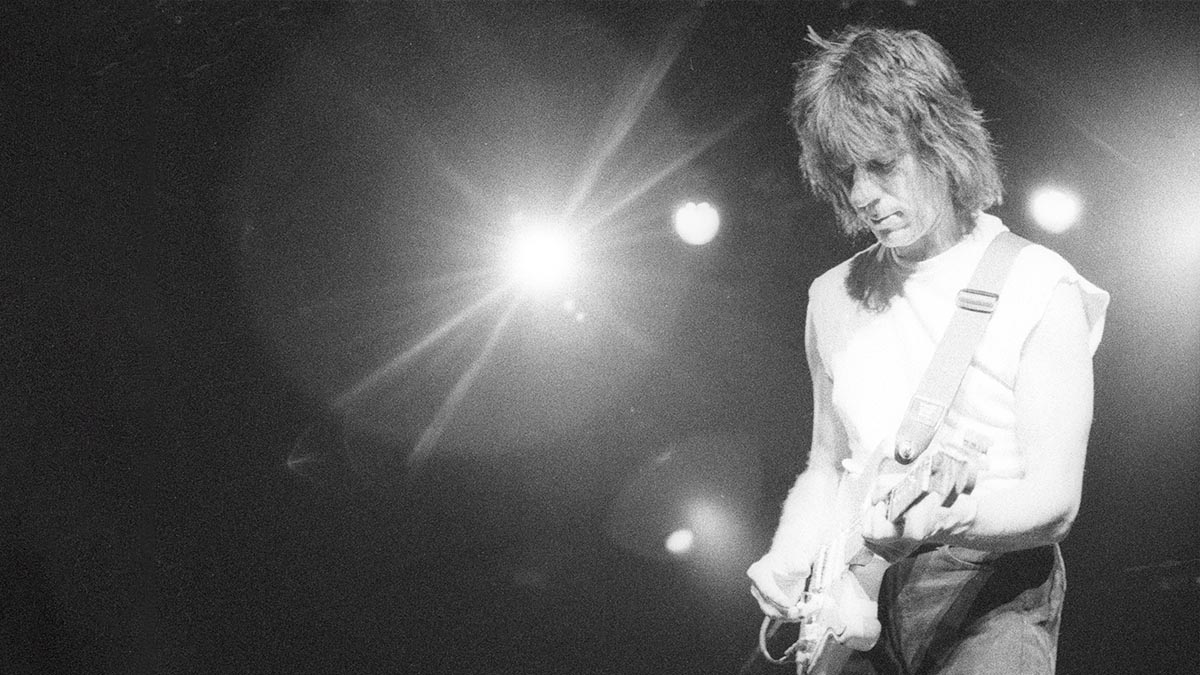

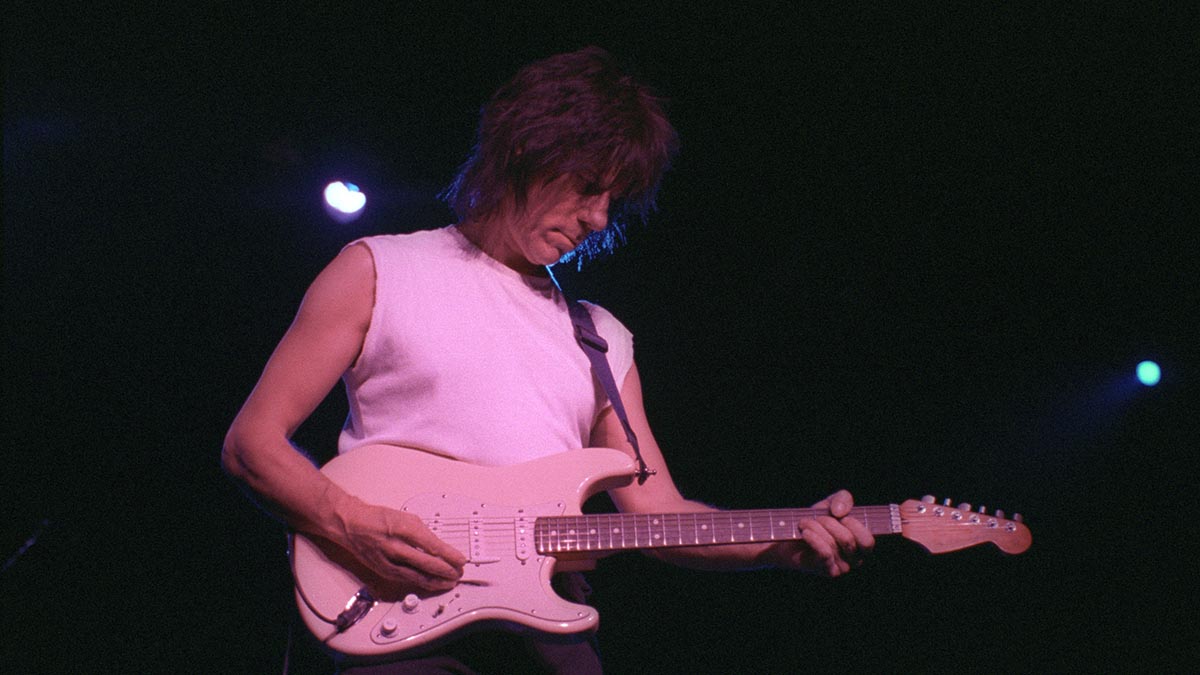

In mid-February of 1999 I flew from San Francisco to London to interview Jeff Beck. I had interviewed Jeff several times before, starting in December 1992 with a wonderful experience at his home in Sussex where we talked at length about his Crazy Legs album and his hero, guitarist Cliff Gallup of Gene Vincent’s Blue Caps.

Over the years, I interviewed him about various projects he was involved in and saw and shot photos of him on tour numerous times. But the one thing I really wanted to do was an in-depth interview with Beck about one of his solo albums.

It took almost 10 years after Beck’s previous solo outing, Guitar Shop, was released, but I finally got the opportunity I was waiting for – Player magazine in Japan flew me to London to interview Jeff about his forthcoming album, Who Else!, and Jeff and I met up on February 19, 1999, at London’s Royal Garden Hotel, near the British royal residence, Kensington Palace.

In the afternoon, I shot photos of him in the private confines of a basement lobby surrounded by meeting rooms, where occasionally a bewildered businessman or two would walk by and give us a confused glare. That evening we met up again at the bar on the hotel’s top floor to do the interview.

When I showed up, Jeff was waiting at the bar and drinking a beer (it was a Beck’s, of course – what else!). We talked about the album’s background, including its beginnings in 1996 with sessions he had done in Los Angeles produced by Steve Lukather, as well as the smoking-hot band consisting of guitarist Jennifer Batten, bassist Randy Hope-Taylor and drummer Steve Alexander, that he formed in 1998 to road test new material.

During the course of the interview, Jeff was extremely and unusually candid, honest and forthcoming about the struggles he went through to bring the album to fruition. My biggest and only regret was that this interview would be published only in Japan and in Japanese.

After Jeff passed away, I revisited this interview for the first time in more than 20 years. The section where he talked about having only a limited time left on this earth choked me to tears. Here he was only 54, and he was already facing his own mortality.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

I’m glad he lived almost another 24 years after that – although I wish he could have stayed with us a lot longer – but I’m especially relieved that he kept the promise he made back then to be more prolific and released five additional studio albums and eight live albums. He also toured frequently. The following is a condensed version of the interview, published for the first time in English.

I’d like to start with the question everyone has probably been asking you…

“Which is, why has it taken me 10 years to come out with a new album? I had a few diversions, subversions, all kinds of things. The last nine years were rough for music. It has been jumping around all over the place like a fox.

“I could never tell where anything was going to go. I was also really depressed about not being able to keep the original three-piece band together: me, Tony Hymas and Terry Bozzio. That was such a cooking band. And the idea was great – for Tony to go bananas on the keyboards and cover bass, rhythm and everything else.

“Unfortunately, we didn’t get the dimension that we wanted. I felt that after the initial tour, the failure of the album [Guitar Shop] to do anything more than a little blip was very depressing. We put a lot of work into it. Bear in mind that Guitar Shop was a startup album as well, after another long period of no output from me. I was doing a lot for other people, and I thought, ‘Well, I can make a living doing this.’

“So I went into this rather uncomfortable but laid-back mode. Unfortunately, the closer you are friends with who you’re working with, the less you’re paid. I often did things for nothing because they were my friends. I got really disillusioned with my playing as well. I knew there were these other guitarists coming up around the block, and they could really play.”

Did you feel like they were a threat?

“Not a threat. It was just telling me it was time to move on. I wasn’t going to let that happen, but they did shove me aside for a while. I just thought I should be an observer rather than a participant. Right in the depths of my depression, I put some money into building a home studio. When all else was lost, I did the one thing I never thought I’d do, and I built my own studio. That gradually started the healing process – not that there was anything broken but me.

When all else was lost, I did the one thing I never thought I’d do, and I built my own studio. That gradually started the healing process – not that there was anything broken but me

“Everyone goes through drug rehab and all that. I never had that problem. But I have other problems, like having difficulty holding relationships together. It’s really confounding to be blasted in the newspapers by a status-climbing girlfriend. It’s a bit rough. It was a compound series of events that I could have done without. The capper of it all was when the newspapers were coming around and banging on my door. I had to wait for all of that stuff to blow over before I felt I could start to pull myself together.”

“I want to talk about my ordeal one day. It’s sufficiently charged with interest, either in novel form or as a biographical movie. There’s a hell of a movie in there. I could sell the rights to Aaron Spelling. You could call it ‘East Sussex, TN 566’ or ‘Sex in East Sussex.’ [Laughs] I also distracted myself by restoring my house, which was a great thing to do. It gave me a complete other interest besides my guitar, cars and getting into trouble. Having made a series of lame excuses, here we are in 1999.”

Did the problems you were having with your relationships influence your music at all?

“I’ve got some pretty deep blues on tapes lying about. I went into this mode where I wanted everything I’ve done that was lying fallow destroyed. All the stuff that was boiling around eventually made it. I got so messed up with loads and loads of tapes that I had no idea what I had done or where it was.

“There were no labels on the DATs or cassettes. I would just shove something in the deck, and if it didn’t make me smile I’d take it right out. Usually it just made me real depressed. On seldom occasions it might have a nice, pristine start to something really good. I didn’t have anybody around to say, 'Wow! That was really good. Stay with it. The hook is great.' I preferred to wait to get Tony Hymas involved so I could pick his writing to pieces instead of criticizing my own work.”

Tony has often been one of your most helpful critics.

“It’s torture for him listening to me trying to interpret his songs. And it’s torture for me to try to interpret his songs, to try to supplant some kind of notion of what I want to do without sounding like some goof who can’t remember what I want. I got pretty graphic with some of the stuff that you hear on the record.”

Is that why things didn’t work out with Steve Lukather? Was he too much of a fan to tell you when he didn’t think things were as good as they could be?

“He came around at a bad time. The idea was to get Steve involved with his wacky humor, but at that time I was about as low as I could get. He did lift me a bit, but it was a temporary thing. It probably would have been better to just let me wallow in my misery for a while. I ended up getting this false sense of elation during the writing period. You’d probably like some of the material. I’m sure there are people who would freak out over it.”

Steve was definitely raving about it.

“There was some good stuff. Don’t get me wrong. I just wasn’t hearing that little birdie whispering in my ear going, ‘This is the stuff.’ If that doesn’t happen, I’m done. I need to go out somewhere else. I need to move along.”

But you put a good amount of time into it. You recorded over at his studio in Los Angeles for a few months and then about a year later the two of you were working at David Gilmour’s studio in London.

“The first initial try out took place at Steve’s studio in Los Angeles. Everything was great. Then I came back to L.A. again to start recording, and I was in the middle of these problems. And I got very ill. It was very serious. I don’t think I felt right for four months. I slowly made a gradual recovery. After three months, I went out and tried to wash my car and fainted. I just brushed the sponge over the roof and I collapsed. I really thought I was finished.

“It was some bizarre strain of Legionnaires disease, not the strain that kills you, but something related to it. It was horrible. I went to the doctor and he said, 'I don’t want to shock you, but I’ve looked at other patients who have the same thing as you and it may take months before you recover.' I didn’t need to hear that.

“Eventually I got better and we started up again at David Gilmour’s studio. Everything was perfect. The weather was wonderful. But we were still stuck in a rut with the material. Along comes Tony with three great tracks that blew everything else I’d written into the weeds. I suddenly sensed there was a disagreeable situation with trying to juxtapose his material on top of what we already had.

“It sounded like another album. We couldn’t make it flow. So I thought that I’d better be faithful to Tony because he’s always written from the heart. What I’d written was promising, but it needed development. Steve is such a good soul that even when I played badly he’d say, ‘Man, it’s boiling hot in here!’ But I needed somebody to push me.”

You share the same affliction that has bothered guitarists like Eric Johnson and Danny Gatton. It seems like what you hear in your head is beyond what your fingers can do.

“Exactly. The fingers are not saying what the head is saying, or the heart. I was just so frustrated because all I needed was a silly-ass melody to get people going. That’s what I do. There are many guitarists who can play like a typewriter. Technically they’re great, but that’s not my style. There’s no Stevie Wonder writing for me anymore. He would write beautiful ballads, and I would just interpret them the way I heard them.”

There was talk of you collaborating with Eric Johnson, and you worked with John McLaughlin. And you’ve been working with Jennifer Batten in your band. Did you start working with other guitarists to push yourself?

“It was more because I wanted to work. But it was a bit of a blow, only having the odd chance to play with people every few months. I found myself getting into the mode where I was thinking, ‘The phone will ring today. Something will happen.’ I have to tell you that’s not likely to happen in my neck of the woods. I don’t have too many musician friends living in my area. In fact, I had very little enthusiasm for any friendship at all the last few years.”

“I have a couple of good friends who aren’t musicians. One is a film director and the other is a mechanic. I get tremendous confidence boosts from them, but not enough musical input. But having said that, the film director friend was a great support when I suggested doing something that was a cross between the Prodigy and myself. He said, ‘That’s the stuff. I could hear that working well.’ So I developed tiny little snippets of this stuff and sizable chunks of other stuff.

What happened with Terry Bozzio? You managed to get him back for your 1995 tour with Santana.

“That was another weird thing. Playing 46 gigs together should have resulted in us coming closer together. Unfortunately, we shouldn’t have done a big, over-the-top tour without a new product. That was bad planning. Doing the gigs was the positive side of the experience. Once again, being disparate characters we pushed each other away.

“Tony was obviously champing at the bit to do his own projects, and Terry was starting to make inroads to superstardom as a drummer in his own right. I’m not going to say, “Hey! Come back here,” and take a piece of rope and drag him back when I didn’t have any new material. It was all down to the big ‘M.’ ‘Where is the bloody material?’

“I’m very sad it didn’t work, especially since we had Pino Palladino on bass. I felt sure that we’d get something going. Even though Tony, Pino and I live in the same country, we might as well live 15,000 miles apart. We live our own lives. People say it only takes two steps to get from one coast to another in England, but it doesn’t matter when you’re living very separate lives. And Terry was living in Austin, Texas, with his wife and baby. It didn’t seem likely, unless we had some really masterful plan, that we could work things out.

“Then we came up with another plan, which was to work with Terry and Tony Levin. It would have been very interesting to have Tony playing Stick. Then Jennifer Batten came along and I thought, ‘Right on! Let’s do a four-piece band.’ I think that would have been incredible. But it seemed that Terry and Tony were just on loan. There wasn’t any camaraderie. There was less than there was with the original band.”

Over the years you’ve developed quite a collaborative relationship with keyboardists, such as Tony Hymas, Jan Hammer, Jed Leiber and Max Middleton. What drives you toward keyboardists?

“The fact that they know chords. [Laughs] The first keyboardist I worked with was Nicky Hopkins, on Beck-ola. He added something, but he also took away something. It was a fair trade at the time. I lost the raucousness. As soon as you hear the piano, it makes things sound civilized. It makes it sound safe and familiar.

“Before that, I could leave holes – dangerous, great chasms where nothing was going on. I had freedom to pop in and out where I wanted with Rod. It was a tennis match – voice against guitar. I could change riffs to catch Rod’s attention. With Ronnie, I could play different riffs and he’d follow me. He’d just look at my fingers. But when you’ve got a keyboard player looking the other way, he gets lost really quickly.”

You went through a few false starts on this album. When did you finally get on the path that led to the finished effort?

“Having gone through all sorts of negative emotions and disasters as well as a colossal loss of money, I suddenly came out of this cloud and went, ‘I’ve got to do something. This is serious.’ I went down and visited Tony and said, ‘Look. Never mind the fancy Lukather session. We need to listen to what I’ve got to say.’ I took a bunch of very interesting techno music to him and he stared at the ground blankly. He didn’t seem to be into it.

“Then the next thing you know Psycho Sam came out of him. I said, ‘That’s what I’m talking about!” I went down to the studio again and threw some more ideas down on tape. Gradually we pieced it together. It was a slow, agonizing process, but when we started hearing how the band was sounding with the new material when we played live it was very promising.

“After that I discovered Declan which was written by an Irish folk artist named Donal Lunny. I love it. It’s a real tear-jerker. If they clap for that song when I play in Ireland, I shall be very happy. I’m worried to see how they respond to this British guitarist playing their hallowed music. I hope I don’t get hit over the head with a bottle of Guinness.

“I’ve never played in Ireland either, except recently when I did a crazy weekend with Ronnie Wood and Scotty Moore with D.J. Fontana on drums. That was amazing fun. I did the All the King’s Men record [1997] with them, which was also great. We recorded so much more material that never made it on the record. But it was so difficult to write stuff for Scotty to play.

“It was a total East/West vibe. There was no excuse for us to play together other than the fact that we respect each other and we wanted people to know that we care for these musicians who are still alive and kicking. Moore and Fontana’s playing was so eclipsed by what happened with Elvis after the Louisiana Hayride.

“I didn’t know that D.J. Fontana was once a member of Gene Vincent’s Blue Caps. He replaced Dickie ‘Be-Bop’ Harrell. What a band that must have been! I have a picture and some lost session tapes of a Dallas show with the Blue Caps Mark II, with D.J. Fontana on drums and Johnny Meeks on guitar. I have some very rare footage that I got from the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

“They showed it at an induction ceremony, and I said, 'You’ve got to send me this. I’m not going to go on stage unless you promise to send it to me.' I’ve got some tapes from Australian television – Johnny Meeks, with blond hair! And they’ve got no caps on. There he is, chewing gum, singing. He is so sharp-looking. The world must have been at their feet back then.”

What inspired you the most when you were making this record?

“I’m a great fan of the Prodigy. They kick butt and they make that great, wallowing-in-the-mud sort of festival music. I love it. It’s like the Who and the Yardbirds. I love their drum sounds. They’re punky, but they’re articulated and beautiful. It’s not trashy.

“I wanted to capture that power with my guitar on top of it. I wanted to marry that notion of techno with a real drummer. I ended up using drum machines some of the time, though. I’m not a purist. I’ll go wherever I need to go to get the result.”

Did you add any new equipment to your rig or are you still using the basic Strat and Marshall setup?

“I don’t have any equipment. [Laughs] It’s still the same old, same old. To me it’s like a ’50s toaster. You just plug it in and switch it on. If I don’t hear me in there, I don’t like what I’m plugged into. There are millions of fantastic guitar sounds, but they always sound exactly the same no matter who's playing.

“They’re not transparent enough to reveal the character. I could use maybe one flurry of notes with that kind of sound, but I prefer the sound of a really loud amp blasting away. I like for there to be some size. I like to hear the room. I don’t like to stuff the mic right up against the cone.”

Your single notes have a horn-like quality, like a saxophone.

“I try to avoid shattering the eardrum. A Stratocaster can be too bright. I kill off all of the top end on the guitar by turning the tone control all the way down, and I set the controls on the amp where the throat is still there. Then I overload it to get this honking, choked-up sound.”

I don’t want to fizzle out and become some retro act

Are we going to have to wait another 10 years for your next album, or have you gotten over that hurdle?

“I don’t know if I have another 10 years left. If for no other reason, I only have a limited amount of birthdays left. It’s about time that I did something. I’m committed in a big way to doing a lot more. I have a lot of stuff left over, so if I see some good results from this I won’t be touching the ground again for quite a while.

“Now that I’m in the latter part of my life, it’s best to enjoy it and appreciate it. I don’t want to fizzle out and become some retro act. I’m really concerned about what is going on out there. Television has sunken to unbelievable depths. I can’t believe that we’re entertained by Jerry Springer and watching people kick the shit out of each other. They emulate that here in England, and it is so cheesy. It makes me want to throw my TV out the window.

“That invention is probably the greatest communicator of the 20th century, but how come for 24 hours a day we get filth like Jerry Springer and all of these rubbishy soaps? There is so much knowledge that is stuffed away that should be on television. If I ever made a million quid I’d start my own TV channel. Why do we need 50 channels of sports or to be able to tune in the Italian weather forecast? I don’t get it.

“The internet is much better. You can search out the information that you want. I’m very relieved that I was born when I was born, and not in the ’70s. I’m not envious of that generation.

“And then there is the whole ‘Girl Power’ thing. I think women are entitled to kick men’s asses, but at the same time they are mocking us. It’s so easy for them to turn a simple peck on the cheek relationship into ‘I’ll have your Cadillac, your Porsche and everything else you have.’ It’s best to have nothing and marry a rich wife.”

You’re much more aware of what is going on around you musically than other 54-year-old rock musicians. Most musicians your age are clinging desperately to the past and trying to revive their past glories. What keeps you looking ahead?

“I never at any phase in my career felt that that was my time, but now I do. Perhaps it is my turn now.”

Chris is the co-author of Eruption - Conversations with Eddie Van Halen. He is a 40-year music industry veteran who started at Boardwalk Entertainment (Joan Jett, Night Ranger) and Roland US before becoming a guitar journalist in 1991. He has interviewed more than 600 artists, written more than 1,400 product reviews and contributed to Jeff Beck’s Beck 01: Hot Rods and Rock & Roll and Eric Clapton’s Six String Stories.

“My guitar tech ran in and said, ‘Hey, you want to meet Pete?’ I was too scared”: The Smithereens’ love affair with The Who goes way back – yet when guitarist Jim Babjak got the chance to meet Pete Townshend, he turned it down

“Every tour was the best I could have done. It was only after that I would listen to more Grateful Dead and realize I hadn’t come close”: John Mayer and Bob Weir reflect on 10 years of Dead & Company – and why the Sphere forced them to reassess everything

![John Mayer and Bob Weir [left] of Dead & Company photographed against a grey background. Mayer wears a blue overshirt and has his signature Silver Sky on his shoulder. Weir wears grey and a bolo tie.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/C6niSAybzVCHoYcpJ8ZZgE.jpg)

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)