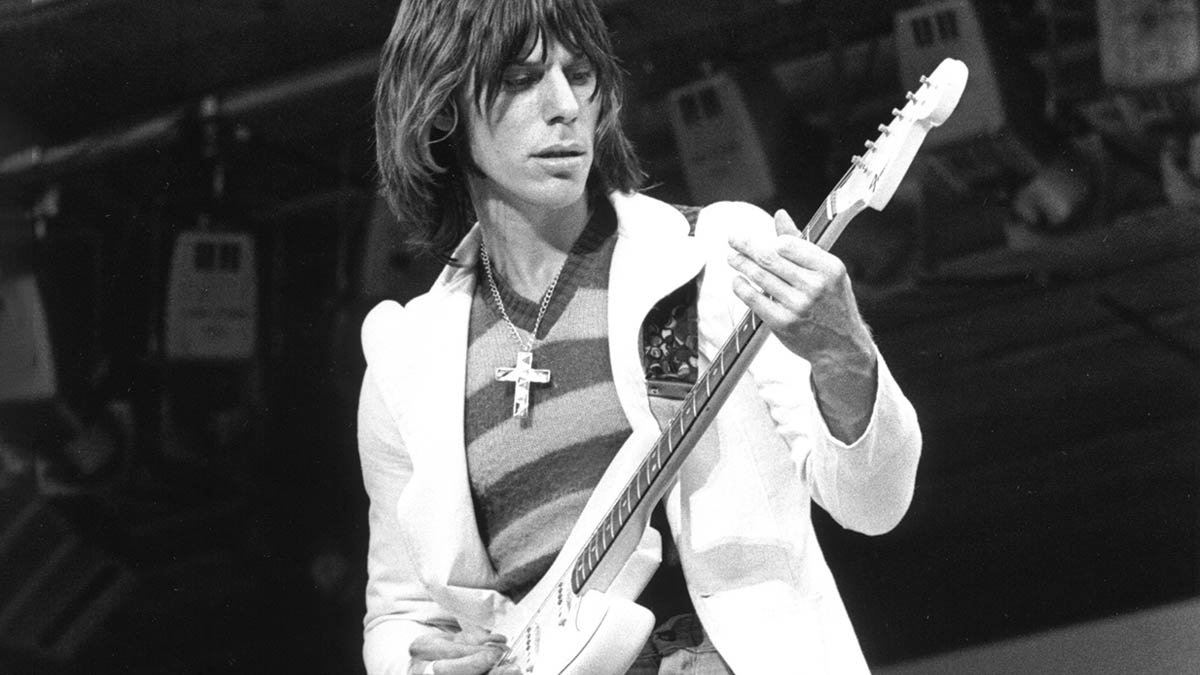

Jeff Beck in his own words: “My Strat is another arm – it’s part of me. It doesn’t feel like a guitar at all… It’s a tool of great inspiration and torture”

In these classic interviews, the late Jeff Beck, a man who typically preferred to let the guitar do the talking, looks back on his career and discusses his gear discoveries and creative epiphanies

Jeff Beck’s playing was unforgettable and unique. Who better than Jeff himself, then, to explain how his approach to guitar evolved? We open the archives to revisit Jeff explaining his art, in his own words, in classic interviews.

His first guitar (Guitarist, Summer 2009)

“My first experience with a guitar was as a kid when I was at a friend’s house who was slightly spoiled, he had a record player, a tape recorder, a guitar – all the toys. He’d got bored with the guitar and it only had a couple of strings on it. I started playing around with it and he said, ‘Do you wanna borrow it?’ I said, ‘Yes, please!’

“I remember carrying it home in the rain and taking my coat off to wrap around it to protect it. Right then, I felt a kind of protective thing towards the guitar. I didn’t have any strings so I used some model aeroplane control line wire, the kind that made the model fly round in circles. The people next-door-but-one had a zither and that was actually the first stringed instrument that I touched.”

Playing a Strat for the first time (Guitarist, Summer 2009)

“Well, me and a friend got a train and a bus up to London from Croydon and we asked a porter where all the guitars were. He happened to know and said Charing Cross Road, so we jumped on a bus, ran upstairs and looked out the window for guitar stores.

“My mate suddenly said, ‘Oh my God!’ We belted down the stairs, stumbling over one another, ran in front of all the traffic and there we found a Tele and a Strat in the window of Jennings Musical Instruments [the original Vox Amplifier Shop, at 100 Charing Cross Road].

“We stood there motionless, salivating, for at least five minutes and my mate said, ‘Shall we go in?’ I said, ‘No, no, we can’t go in!’ We were completely freaked out.

“After a while we went in and I said, ‘I’d like to try the Fender Stratocaster, please,’ and the guy said, ‘Yes, gentlemen, certainly sir. You are intending to buy it, are you?’ We didn’t have a pot to piss in, but we said, ‘Yeah, yeah…’ I played it for a while and it was a totally magical experience. Then I put my muddy boot up on an amp and the guy said, ‘Right, get out!’ I was happy that I’d played the Strat and didn’t care about being thrown out of the store.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

We made friends with a sales guy who used to let us play any guitar in the shop. He was great, he’d leave us alone and say, ‘Just don’t nick anything!’

“The next time I went back, the guy says, ‘Hmm, I remember you…’ I started playing some Chet Atkins on the Strat and people started coming in off the street to listen. The guy says, ‘Keep playing, keep playing!’ I thought, ‘You bastard! I’m getting all your bloody customers for you, I’ll put my foot on your amp all day long!’

“The place always smelled of pipe smoke and the sales guys were very intimidating. Another shop in Charing Cross Road we used to bug was called Lew Davis. There we discovered a slapback echo device and we were in heaven.

“We made friends with a sales guy who used to let us play any guitar in the shop. He was great, he’d leave us alone and say, ‘Just don’t nick anything!’ We never did and they couldn’t get rid of us. Then some 15-year-old kid would come in and his dad would buy him a Strat outright for cash. Case and all! Strap, strings, pick… We’d sit there scowling.”

Going solo after The Yardbirds (Guitarist, Summer 2009)

“I enjoy talking about these times – they’re still fresh in my head. They were wonderful times and, unfortunately, they didn’t last for us because The Yardbirds depended more heavily on guitar than they knew until I walked out, or was thrown out. I was a bit upset about the non-stop touring and the package tours without any real reward.

“I hardly saw any money and then I got really ill and thought, ‘Why am I doing this for 60 bucks a week?’ We’d had three chart successes in England and I thought, ‘What’s going on?’ I ate bad fish in France and got food poisoning. I was sick for four days in this hotel and the rest of the band left me to go night‑clubbing in St Tropez.

“My head hurt so much I couldn’t even move it on the pillow. When it eventually subsided someone put me on a plane back to England and I don’t even know how I got home. I wanted the band to call me, but they’d gone to Australia without me.

“I just went to ground. A fan found out where I lived and he pretty much saved my life. It was the lowest point in my career. I was on special painkillers and this fan saw my Corvette outside, knocked on my door and said, ‘You can’t drive, you’re too ill.’ I said, ‘Who the hell are you?’ He showed me a newspaper report that the band had gone on tour and said, ‘You’ve got to get the bus,’ and he took care of me.

“I got thrown out of my lodgings, went back home and my mum said, ‘Get out, we don’t want you here, either!’ How much worse could it get? Then finally things started to turn around and I started getting some success in my own name. I had a couple of hits in 1967 with Hi Ho Silver Lining and Tallyman.”

Relying on guitar alone (Total Guitar, September 2016)

“It’s so difficult because I didn’t sing. Eric [Clapton] said, and it was words of great wisdom, ‘Get used to the fact that you hate your voice because I did.’ And I went, ‘But you sound good; I sound unbearably bad. I loathe it.’ I would never enjoy it even if we had another single like [Hi Ho] Silver Lining, I just couldn’t bear it. He said, ‘I’m telling you, if you don’t, it’s going to be tough.’

“And it was tough, but then I can turn around and say, ‘Blow By Blow, put that in your pipe and smoke it, mate.’ But he’s right, if I did come up with a song and everybody loved it, it would instil confidence automatically and I might even get to like what I sound like, but letting that out there is more than I can bear.

Every musician I knew was raving about Mahavishnu Orchestra. I thought, ‘This is a little bit of me, this. I’ll have some of that.’ The mastery of the playing, it was unequalled

“It’s just not me. I listen to Jimi who had a peculiar voice and it wasn’t a great voice, but it was just magic. He never did scream, it was always the guitar that screamed for him and I still marvel at him even today.

“I never listened to more Jimi than I do now because I’ve got some really rare recordings, it’s just humiliating to know that he was doing that up to 1970, all in a period of about three-and-a-half years.

“Things took a funny turn in the early ’70s. It all turned out well when I heard John McLaughlin because his performance on the Miles Davis Jack Johnson album and with Mahavishnu Orchestra said, ‘Here’s where you can go.’ And every musician I knew was raving about them. I thought, ‘This is a little bit of me, this. I’ll have some of that.’ The mastery of the playing, it was unequalled.”

On reinventing himself (Total Guitar, September 2016)

“I think it’s good to do that and it’s been easy because if you have a massive hit, where are you going to go? You’ll make the worst step ever and slip over, but not having any big hits – and I mean giant hits – it makes it a lot easier to just jump into another genre because you’re not cheating somebody out of something they like. I’m an experimenter. It’s rich because every album I’ve done, except for a couple of techno-y records, is different.”

On the nature of Strats (Total Guitar, September 2016)

“My Strat is another arm – it’s part of me. It doesn’t feel like a guitar at all. It’s an implement which is my voice. A Les Paul feels like a guitar and I play differently on that and I sound too much like someone else. With the Strat, instantly it becomes mine so that’s why I’ve welded myself to that. Or it’s welded itself to me, one or the other.

“Really, you’ve got to hand it to the Fender Strat because there are songs in [that guitar]. It’s a tool of great inspiration and torture at the same time because it’s forever sitting there challenging you to find something else in it, but it is there if you really search. It does respond to touch and the tonal variation is unlimited, really, especially with the whammy bar. I have it set up so it becomes almost like a pedal steel.”

What being a musician means (Guitarist, Summer 2009)

“It probably didn’t actually cross my mind until a few years ago when I realised that all the things I hated, such as the touring and the long bus journeys, once you come to terms with the fact that this is what you have to do and then start enjoying it, then it’s not a problem.

“I go 600 miles on a bus now, whereas in the past I would refuse to go six miles without screaming about it. It’s better than flying and we have a lot of fun. There’s all the thorny edginess of a soap opera wrapped up in a tour, but it’s part of life and you’re enjoying life in a kind of private bubble. Everyone has their jokes, their humour, their problems and it’s great. It’s a whole life in a bus.

“You get to be a gypsy for three months and feel like you’re exempt from any outside responsibilities. I would never have believed it, but I’ve just started to take a laptop on the road to keep in touch with home via the internet! Being a musician means everything to me.”

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.

“Such a rare piece”: Dave Navarro has chosen the guitar he’s using to record his first post-Jane’s Addiction material – and it’s a historic build

“The best guitar player I ever heard”: Nashville guitar extraordinaire Mac Gayden – who worked with Bob Dylan, Elvis, Linda Ronstadt and Simon & Garfunkel – dies at 83

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)