Jeff Beck Discusses Gear, Technique and Hendrix in 1985 Guitar World Interview, Part 2

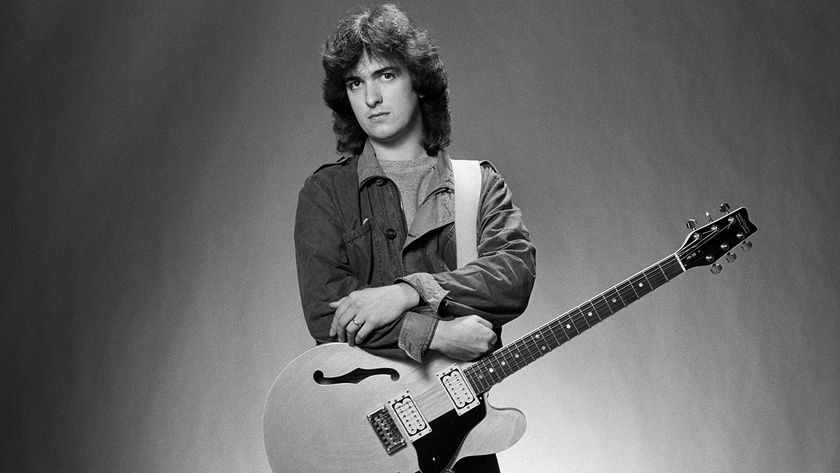

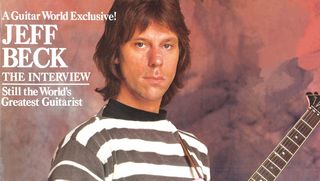

Here's part two of our interview with Jeff Beck from the March 1985 issue of Guitar World, which featured Ron Wood on the cover (Part one of the interview is from the January 1985 issue, which featured Beck on the cover). This half of the story also features input from Seymour Duncan, Stanley Clarke, Jan Hammer, Chris Dreja and Jim McCarty.

Part II of our encounter with rock's Jack of Spades takes the form of this survey of the many musical milestones in Jeff Beck's consistently astonishing career. The Yardbirds, The Jeff Beck Group, The ARMS Tour and beyond –- all are heard from in this special report.

Since 1964, when he first put it down on wax, there’s been no doubt about it: Jeff Beck has a sound, a way with the guitar that's at once unique and characteristic, instantly recognizable yet constantly evolving. Unlike many of his contemporaries among the sixties guitar heroes, Beck has had the courage to try on a number of musical styles for size; and if there have been, inevitably, times when he's seemed like the fairy-tale emperor with no clothes, he's nevertheless continued to live up to his role as one of the great guitar innovators.

Whatever the musical setting, though, there are singular elements in a Jeff Beck solo, a style that tells you immediately who's at work. Some of those elements are easier than others to point out: his extremely strong wrist and finger vibrato; his fierce attack and fat tone; his acute microtonal sense of pitch when he bends or slides into a note; his adroit manipulation of the tremolo bar to stretch a note into a phrase; his highly developed sense of phrasing, unusual in a rock guitarist for its rhythmic and melodic sophistication; his frequent use of double stops and slides; his ability to wring painfully true notes from beyond the twentieth fret; and perhaps most significantly for the development of rock guitar, his deep understanding of the electric guitar as an electric instrument, which means that over the years Beck has been one of the explorers of the guitar solo as a configuration of sounds and textures rather than simply of notes. Add the magic of inspiration and you've got the net result: a Beck solo that sounds like no one else's.

Staying a pop culture hero for twenty years is no mean feat; and Beck's recent return to the musical fray, with Mick Jagger, Rod Stewart, Tina Turner, Stanley Clarke and his old Yardbirds mates on Box of Frogs, marks his emergence from three years of near-silence. With the imminent release of his own Get Workin' LP, produced by the ubiquitous Nile Rodgers, it seemed to us at GW that the time was right to try to put the career, the achievements, the musicianship of one of the all-time great ax-slingers into some kind of perspective.

That's why we thought the scrapbook appropriate. Here are the observations and comments of the man himself, as well as those of some of the musicians who've worked most closely with him over the years. We hope that the portrait that emerges of the musician-and the man-will help shed light on the most important thing: the music of Jeff Beck.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

GUITAR WORLD: How do you approach your solos? Are you a spontaneous or a planned player?

I'm a very emotional person. If I've got something on my mind, that would stop me from giving my best. That's why it's not a good idea for people to ring me up and ask me to save an iffy track, because I might put it further in the dark. If I'm on form and I'm not being bothered too much by mental problems or whatever, I can whip out something good. That's why I've done quite a few overdubs for Tina Turner and things like that, because even before she made this comeback I said yes to her, just because I love Tina Turner.

And besides, I thought, this is a good way of getting out of a depression: just seeing somebody else's problems on tape, and then seeing the slot that they want me to fill in, gets my mind to working at about a hundred miles an hour, because I've got to be quick and I've got to thrill them, all in about two or three hours' time. That is a great challenge. It's something you can hardly duplicate for yourself because you know you've got more time if you need it. Besides, it's good fun doing it.

The fun and the challenge both show on the tracks you did for Tina.

Well, I play purely from the heart, y'know, and so if it doesn't work the first couple of hours, forget it. Unless we feel like we're somehow on the right track then I'll keep on going. That's it, really; I don't have any magic where I just press a button and it happens. It'll either happen or it won't. With Tina I had a fantastic time -- we got blasted at the end of the sessions, and she carved her name onto my guitar with an ice pick [laughs].

Rumor has it that you've dropped a couple of solos on Mick Jagger's solo LP as well.

Oh, I did more than that: I went down to Compass Point with Bill Laswell for three weeks, and I did seven tracks with him, I think. But I don't know exactly how much of that stuff he's using yet. [Ed. note: at deadline time, Jagger's solo LP still hadn't been mixed.]

A lot of guitarists tend to play in the patterns that just naturally fall under their fingers and repeat themselves because of it. But that doesn't seem to be the way you play.

Well, it's no use playing round on a blues mode if the tune you have doesn't have anything to do with that type of mood. If it's a major thing, then you're much freer to do more futuristic stuff, but with a minor key you're really restricted, you can't piss about too much with it. If it's a ballad you can pick up on the melody line from the singer and jazz around with it, and then it's up to the artist and the producer to say how much jazzing about they can put up with. Sometimes when I do an overdub solo, they'll keep four or five of my attempts and then mix the bits that they like to make a solo up out of them. It's not against the rules, really -- I can learn my own solos then [laughs]. But that's the whole beauty of multi-track recording, isn't it?

Your sound is so immediately recognizable -- when you hear a Jeff Beck solo, no matter where, you know right away who it is.

Yeah, I'm afraid the stain is dyed right through to the bones now, I can never get that out [laughs].

Well, what do you think are the essential ingredients of the Jeff Beck sound?

Just total lunacy, really. I think the thing to do is to forget that you're going to make a dreadful mistake and just play on straight through it. Go for one of those glorious moments that happen. If it happens everybody's hopping up and down with delight and if it doesn't they're laughing [laughs], so you try some other tack. I don't think most solos sound much good when the guy sits down and works out exactly what he's going to do. It's different if it's a hook that's going to be on AM radio, then it's worth doing it that way; but I don't really do that sort of song, y'know.

Do you have any favorite solos from all the records you've made?

No, not really. They usually trigger off a memory that has nothing to do with the playing, some personal thing I went through. It's not until somebody else comes up and reminds me of something I've done that I'll even think about it. I'm just thinking about tomorrow, which is a good sign because they say when you're thinking about yesterday you're too old.

You must feel the pressure of being Jeff Beck, in quotes, with people waiting for you to play can-you-top-this all the time.

Well, yeah, obviously. You've got to brace yourself and be brave and go out there and give the people something you can't just hide away. But like you say, when people are just starting to get into stuff that I did five years ago, like the puns in "Space Boogie" and "Star Cycle" off the last album [There and Back] -- well, there are kids of twenty who've just dialed in to that. It's good, but I wish they would listen a bit closer the first time around, because I can't re-release that. I've got to go on to say something new.

Speaking about a long time, do you get any flack from the record company about how long things take for you to do?

No, I think they've been the most wonderful, enduring company. They have respect for me, so they haven't pushed me about it. Any other record company would've just potted me away, I think [laughs]. They're getting a little bit worried now because the record is so powerful that they want to make sure it's channeled in a very between-the-balls way: they want a sure-fire hit album, I think, and they want to feel part of it, which is good. In the old days I'd just turn up at Epic in New York with the master tapes and they'd say thank you very much and take me out for a meal, and that would be the end of it. But nowadays record companies really want hits on a record more than they ever did; they want to hear five or six hits on an album.

That's the Michael Jackson syndrome.

Yeah, he set the standard for everybody else, I think.

Thirty-five million records is kind of an impossible standard.

But I'm glad he did that, because Epic got off my back a bit when that money started rolling in [laughs]. But they've really been good.

If you had a dream project that you could suddenly do, what would it be?

I've often toyed with the idea of doing a rock thing with a full orchestra. I listen to classical music all the time, and I often wish that I was playing somewhere in the beautiful, wide sound that a full orchestra gets. I don't think anybody's really done that yet. You'd put the guitar where, say, an opera singer would be, so that there'd be vast spaces where the guitar would solo, and then would come these huge attacks -- very exciting and dramatic stuff, that's what I have in mind. I've laid some groundwork for that kind of thing, actually, made some inquiries with composers, but they're really not talking the same language half the time. I'd have to write the music for it to work, and somehow I just don't seem to get round to doing that [laughs].

Are there any composers in particular that you listen to?

Not really. I don't try to lift ideas or inspiration from it that way. It might just be one piece that hits me on the radio: melodically, you can pick up a hell of a lot from that, probably more so than if you were listening to a rock station. Of course, that's just me, but it might be worth somebody out there listening to those things; too many people snap them off immediately because they're not rock and roll. But it's beautiful stuff being played by amazing musicians, and even though you may not copy something directly, you may be more inspired to think of your own original style. A lot of players don't do that these days; they just copy one another.

JIM McCARTY on Beck the Unpredictable:

Jim McCarty played drums in the Yardbirds, as well as adding background vocals and co-writing the tunes. He's known Beck for twenty years, and after a sixteen-year hiatus, worked with him again on the Box of Frogs LP.

Working with Jeff in the Yardbirds was up and down a lot of the time, because we really expected quite a bit from him-after all, he had to follow in the footsteps of Eric Clapton. He wasn't really used to that pressure; suddenly he was in the big time, because when he joined the group we became #1 with "For Your Love." So I think he used to panic quite a bit, but he soon got into the swing of things.

The great thing about Jeff was, because we leaned on him so much -- we relied on him to fill up the sound -- he developed a lot of his futuristic ideas, things that people called gimmicks at the time. We'd been used to playing with Clapton, who was playing much straighter r&b solos, and then Jeff was something much wider -- he was interested in people like Les Paul, and all these footpedals and fuzztones and feedback, something we haven't had before which was very exciting.

It was always unpredictable what he'd do, because maybe if he didn't like the sound of his amp he'd just kick it offstage. His playing is still unpredictable: it's never what you 'd expect. If you ask him to play a solo, he'll play something just off the top of his head, and you'll think, what's he doing, playing a different song? Then when you hear it back a few times you realize it really is a great solo. That's what happened again with Box of Frogs. He just seems to be so far ahead all the time.

The problem for Jeff is that he always has to think in terms of what he's going to do next: he has to live up to the name. I still think he's the greatest rock guitarist there is, and he's still got a lot of very far-reaching ideas. But he's a complex character, isn't he? I mean, he plays from his heart all the time, and it takes quite a lot out of him. I know that he's spent periods where he hasn't even gotten out of bed because he's been so low. But he's come back, and he's playing rock and roll again, which I think is great.

SEYMOUR DUNCAN on His Favorite Rock and Roll Player

Seymour Duncan, who manufactures pickups and amplifiers, has worked closely with Beck on his equipment.

I had met Beck earlier but I really got working with him personally in about 1973. He was recording at CBS, doing his second album with BBA. One day his crew manager, Ralph Baker, invited me over because he knew how much of a Beck freak I was. I had this guitar neck, a Telecaster neck that I took the rose of Singapore off and put maple Singapore on with large Gibson frets, and so I took that over to Jeff, and he said, Oh, this is great.

So a few days later I brought back this Telecaster, which I put two humbuckers in and cut the tailpiece so I could get the humbuckers closer to the bridge, and I put a new type of maple neck with Gibson frets on it. Well, he just fell in love with the guitar, and I found out that he recorded "Cause We Ended as Lovers" with it. He could do the volume and tone control thing on it so well, where on the Les Paul he couldn't. To this day he still uses that guitar for sessions, and I was pretty proud of it.

As far as what Jeff looks for in a pickup for his sound, he needs something that will keep up with him, that will respond when he hits a note a certain way, because he relies on his picking technique to make contrasts in his music. So he doesn't want to hit a note soft and have the same sound as when he's hitting it hard. Really, he's looking for a medium output, not a high.

That's why I designed the J.B. Humbucker. I know he doesn't endorse anything, but it was just my appreciation of him. It's a pickup that when you play it, you get out of it what you put into it. So when Jeff plays soft and subtle, and then when he goes crazy on the fingerboard, it'll respond to all that-to the sensitivity of the playing, to the harshness and everything. It's like you're talking with the guitar. Before this, he'd used a whole variety of pickups, from catalog Strats to standard humbuckers to Alnico Twos. The Alnicos are what he's been using for some time: I had them in the old Steve Marriott sunburst Strat he used on There and Back.

Jeff's an amazing player. At the ARMS show we were trying out new pickups and stuff, and he started playing things I never knew he could play, free jazz and things like that. It's another side of him you never see. But he has to have things right for him-the right sound and the right guitar. He's been in a real happy part of his life for the past six to eight months, doing a lot of great things, recording with a lot of people and having a great time. I've listened to him over the years going through all the different changes, the different types of playing, and he's still my favorite rock and roll guitar player.

CHRIS DREJA on Jeff’s Emotional Quality

Chris Dreja played rhythm guitar, and later bass, in The Yardbirds, did background vocals and co-wrote the music. He, too, plays on Box of Frogs.

I'll tell you, in those days Jeff spoke very much through his guitar-it was as if when he started to play he became this amazing multiple personality. It was just incredible. We all feel, I think, that the period Jeff spent with the band was the most creative. Bear in mind that we played with three guitar players, none of them slouches; but if you asked me who I still liked to listen to, I'd definitely say Jeff. His scope of inventiveness was probably the widest of the three, and coupled with his emotional quality it made him my favorite to play with. See, Jeff can play very aggressive stuff that's not like brain damage because there's an emotional quality about it that's extremely pleasant even when it's high-powered. That's something that's in the soul, and it gives his playing a durable quality.

It was a very memorable occasion getting back together with him for Box of Frogs. The thing about Jeff is that we always found he was well able to come in and wrap himself around anything we had written; he'd come in and put the melon on top - know what I mean? Quite honestly, in the fifteen-year gap since we last worked together that hasn't changed at all. There is a sort of chemical thing there, so much so that after all these years it still works.

He's so original, he just thinks from a totally different perspective: you never know quite where you're going with Jeff. He doesn't string notes together in the obvious ways; even if he has to play in a style that needs to be identifiable, he'll play it on the fretboard in such a way that it becomes totally original. For example, he has an ability to go from a low note to a high note like I've never seen anybody else do: you wonder how he's done it, you figure that there has to be an overdub, but he's doing it all at once. The quality of the notes and that actual sound that he gets is very identifiable, such a positive, rock-solid sound. And it just flows out of him.

JAN HAMMER on Working With a Guitar Manhandler

Keyboardist Jan Hammer played with Beck at the height of his fusion period, furnished Beck with tunes and mixed many of their joint efforts.

I would say Jeff's method of working is always pretty much the same: all very spontaneous and very natural, which is what makes him so special. There's very little thought involved, which always makes the best music. His sound is him, it's the hands, it's how he handles- or manhandles- a guitar. The tone doesn't live alone, it's not separated from the notes that he's playing. The distinctive quality comes partly from inspiration, obviously, and partly from the tone, but really from a combination of these elements as shaped by his hands.

I'm not a guitar player-I'm a very very amateur picker-but I can tell l one thing: he gets away with things that are totally illegal as far as how you should play. There are certain things that are not fast in a classical sense, where you say, Oh, this guy studied, he's got technique-like an AI DiMeola or a John McLaughlin, that kind of speed. But this guy gets by on such short cuts; it's astounding, you know, because he's obviously cheating, from a classical point of view. But I don't consider that cheating because I do the same thing- we're on the same wavelength. If there's a way to do something you see, why not do it that way?

That's what makes Beck so astounding, to the point where people will think he's playing two parts. I remember he played me some stuff once where there were two rhythm parts, some old Motown things. He played them for me himself. See, when he first heard them he didn't know that there were two rhythm guitarists doing two parts, so he just figured it out himself and learned to play both parts at once.

People talk about his ego, but I never really saw his ego at work: whenever there were troubles it was more because he wanted so much to be validated and accepted by his peers. Somehow, at certain times in his career, he didn't believe that he was making it, he felt he wanted to be good enough to impress any musician and he didn’t 't realize he was doing it. So he went through these introspective periods where he felt he had to pull back, even though it meant cancelling forty cities and blowing millions of dollars.

STANLEY CLARKE on Working With a True Artist

Stanley Clarke knows how to bend a few strings himself, and he 's had the chance to play with Beck on several studio dates as well as during a world tour.

The thing that I liked most about Jeff was that his music is very much like the way he is as a person, very exciting, pumped-up. When you 're around Jeff at his house, he's into his cars, kinda laidback; but once you get close to him and really know him well you can see that all that is a front-inside he's wild. But only on certain occasions, like when you're on tour, do you get to see that, the real Jeff. For me it was great to play with him, because I love people who have an overabundance of energy: sometimes when you play with musicians you get a feeling like you're wearing them down, and it makes you play less. But Jeff's got a well of energy. It's a shame the band we had never got to play the States.

The real genius of Jeff Beck is that he plays on the fact that he's not a schooled musician, and I think he's one of the few artists that has it really working for him the things he comes up with are truly spontaneous. If you sit with Jeff and try to talk with him about music, like if I was talking to somebody I went to school with, he'd say, Wait a minute, man, this guy here, are you sure he can play?

So you don't talk to about music. Any of the music we did together we never talked about, we just put it together, and the nice thing is that it's put together with the same care that a classical musician would take-the guy knows exactly what he wants to do. I remember one of my albums that he played on. He came into the studio at about one a.m., and I was blown out because I'd worked from twelve in the afternoon. So I said, Jeff, you've gotta get this thing in an hour, man, and he just said, No, mate. So they got the coffee up and I passed out, woke up at seven a.m. and the shit was there, it was burning. He just took the time, and you'll wait for him because you know that you 're gonna have something that you're gonna be listening to and digging as a fan. A true artist.

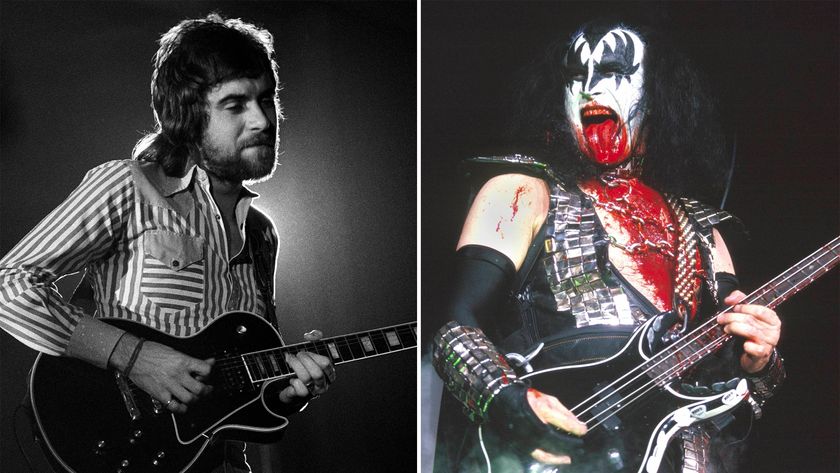

“I had to use the same microphone that Gene Simmons used with all the blood coming out of his mouth. Can you imagine that!”: Mick Rogers recalls Kiss supporting Manfred Mann's Earth Band in their early days

“It’s a whole new generation in sound. There’s nothing lacking”: Alex Lifeson reveals the gear that has finally converted him to digital modeling