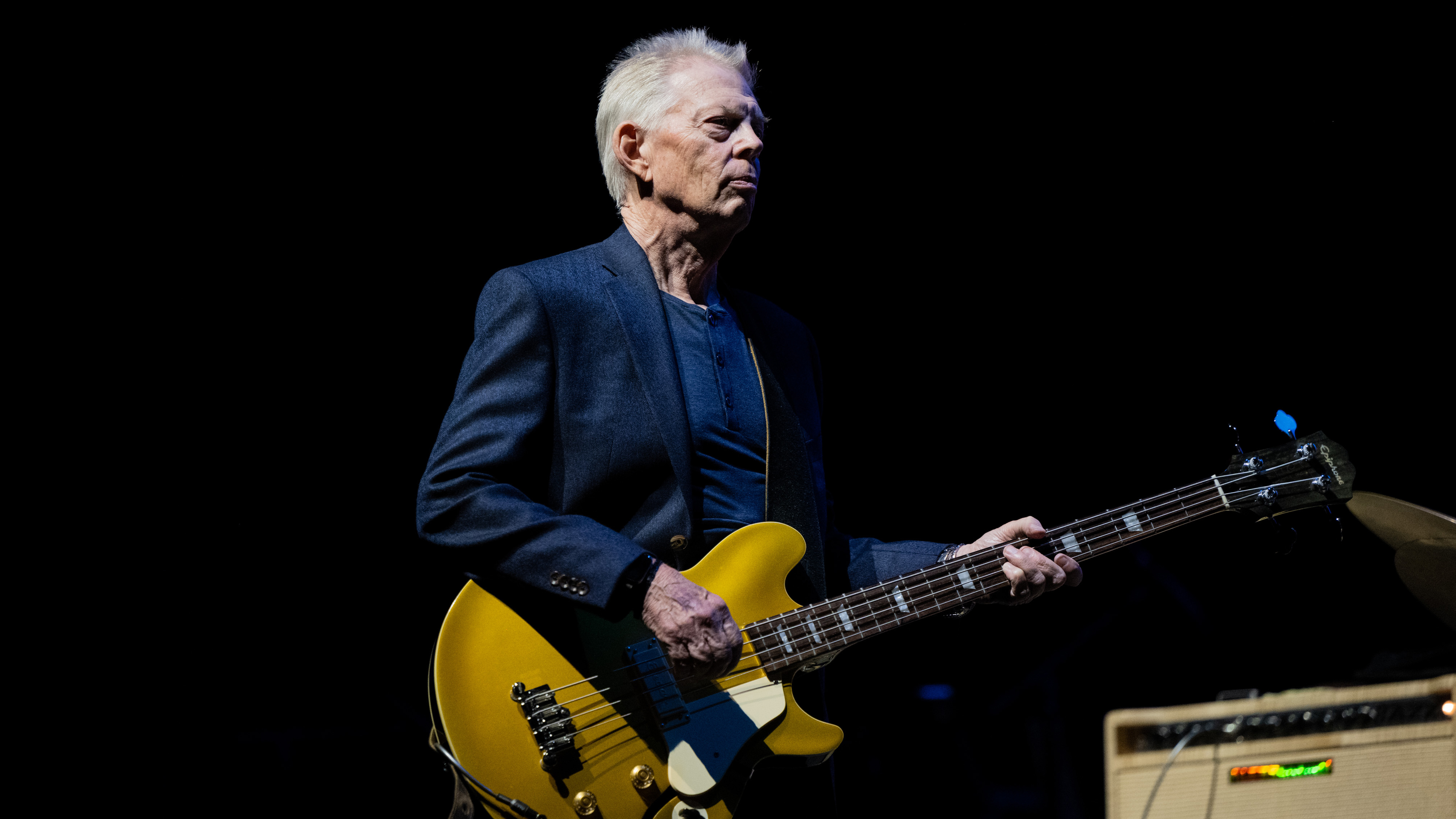

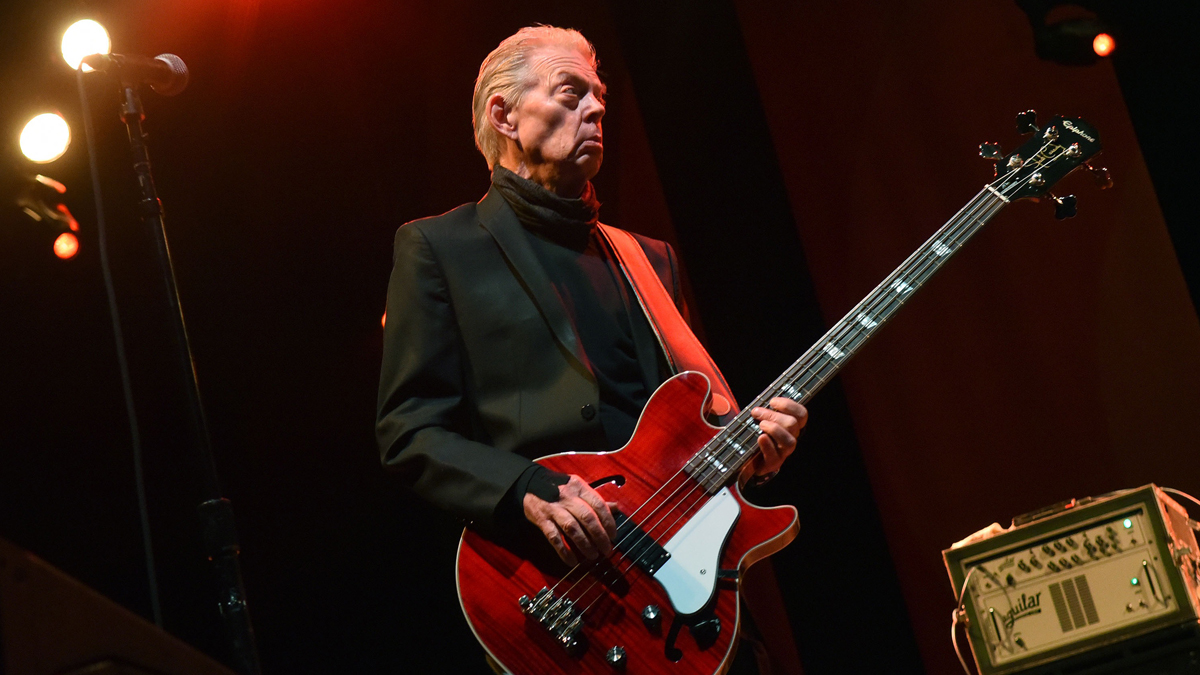

Jefferson Airplane's Jack Casady on why he plays hollowbody basses, road-testing his Epiphone signature models, and the most pivotal point of his playing career

As he hits the road with Hot Tuna, the low-end legend talks all things bass, and recalls how Jefferson Airplane crafted their 1967 psychedelic rock classic, Surrealistic Pillow

Long considered one of rock’s first bass heroes, Jack Casady has been thumping and plucking four-strings in front of audiences since the mid ‘60s – first as a member of the Jefferson Airplane, and then as part of Hot Tuna.

At the age of 78, he still enjoys playing, with Hot Tuna – which features Casady and his long-time musical partner/collaborator/guitarist Jorma Kaukonen – set to close out 2022 with a string of live dates in the US.

Casady has played several bass models over the years, but the two he is most synonymous with are electric-hollowbodied instruments – a Guild Starfire early on, and then later his Epiphone Jack Casady Signature Bass, which resembles the Gibson Les Paul Signature Bass from the '70s.

To this day, the bassist continues to collect accolades for his work. This past October, Jefferson Airplane were given their own star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, the ceremony of which was attended by the band’s sole surviving members: Casady, Kaukonen, and Grace Slick. Fittingly, the star is located right in front of Musician’s Institute.

The four-string veteran spoke with Guitar World shortly before he was due to hit the road once again, discussing his trademark basses, a pivotal moment in his playing, and Jefferson Airplane's 1967 psychedelic rock classic, Surrealistic Pillow, which turned 55 years old this year.

What drew you to semi-hollow basses in the first place?

“I started playing guitar at 12 and bass at 16 in the 1960s, when I could first get my hands on a bass guitar. A Fender bass – I did a fill-in job with it, using the new Precision that was out.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“And then that year, the Jazz Bass had come out and I fell in love with the instrument. I played it all summer when I was 16 in Washington in a club band with Danny Gatton. I modified that Jazz Bass when I came out to California to join the Jefferson Airplane within the first three months of their formation, through a conversation with Jorma, because we had been in a high school band in 1958 together.

“I played the first three albums with that Jazz Bass with a P-pickup in it, so it was really a three-pickup instrument. But I always loved the sound of stand-up bass tones, and that’s why I’m really drawn to Jorma’s guitar playing with an acoustic guitar. I always wanted to match something up that wasn’t quite as brittle as a solid-body instrument.

“So, after the first three albums with Jefferson Airplane, I discovered a Guild Starfire bass, semi-hollowbody, and I really liked it.

“It had some of the tone qualities of an acoustic instrument, and I was able to do some harmonic things: working with overtones and getting a fuller bass sound. It would be like me chasing the stand-up bass sound on an electric instrument.

“And once I found that semi-hollowbody Guild Starfire, I dove into working with the electronics with Owsley Stanley. We modified the electronics and boosted the Alnico magnet pickups.

“Back in those days we were chasing a hi-fi sound – we were trying to get better fidelity all the time. I learned all that from my father, who was a dentist, but as a hobby he was an audiophile. He loved to make amplifiers and put sound systems together to listen to records and get better fidelity.

“So, I was kind of trained in that – to get something that sounded a little better.”

How have your bass choices changed over the years?

“I chose instruments based on tone. There’s so much stuff out there to play, and of course, you can get into collecting instruments, and that’s another matter altogether. But really, I don’t have too much use for an instrument that doesn’t make me want to play it.

“So, over the years, I’ve had my hand in developing instruments. Two instruments – one is in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the second generation of that Starfire bass. The first one got stolen right after I played it at Woodstock – with the customized electronics in it – and that got returned to me 48 years later.

“I played with SVT for a while when Hot Tuna took a little hiatus in the late ‘70s, and in the mid ‘80s I went back to playing a number of solidbody basses with really long scales and round-wound strings, and tried different sound combinations. But I went back to that hollowbody sound when I discovered a hollowbody Les Paul bass that was briefly put out in the early ‘70s.

“In the late ‘90s, through a gentleman that worked at Gibson/Epiphone, Mike Lawson, he put me through to Gibson and then Epiphone, so I could do a sort of ‘rebirth’ to this bass. But I wanted to build the pickups myself and change a few things on it. So, I was able to do that, and the Jack Casady Epiphone Bass is a true hollowbody.

“The Guild had a block down the back, and that block was designed to prevent any kind of feedback that hollowbodies would have if you’re playing at a loud volume. This bass was designed with a fluted piece that was glued to the back of the bass on the inside, but only about three-eighths of an inch in height – so it actually left a hollowed space inside the bass, and it had a really nice, sweet tone to it.

“But one of the other big differences was it had a full-scale 34-inch neck, whereas the Guild Starfire had a short-scale. There were things that you lose and gain with a short-scale and long-scale neck.

“We put that together in ’97, and I’m proud to say it's still selling really well, and I’m really proud of it. Every time there is a new production run – which is about every two years – I take two right off the top, nothing special about them, set them up, put my strings on them, go out, and play right away.

“Now, of course I’ve got some basses that have matured and are 20/30 years old, and you like to play those because there’s the warmth that comes from the age. But, I would say that since I’ve had that Jack Casady Bass out, I’ve changed the basses every time there’s a new production run and I play it in person to make sure it’s good. So, I’ve got hands on with that product.”

Can you pinpoint a pivotal moment with your bass playing?

“I’ve got to say probably going into the studio for the first time. And don’t forget, I had a tape recorder – a 1959 Wollensak, which was the high-end personal tape recorder. So, I had my hands a little bit in the recording world.

“But most folks didn’t even get a chance to hear what they sounded like – unless you had a recording contact and got into the studio. It was a great revelation for me to get in a studio and hear back what I actually sounded like. That was a big moment for me.

“And to have those early years doing the Takes Off album and then Surrealistic Pillow, that was a time to get in the studio and have fun in the there for its own sake. Up until then, it was pretty much a case of trying to get the sound you got on stage in the studio.

“And once you realize that that could only go so far, you started to enjoy that atmosphere and uniqueness to that sound environment in the studio, and start to work with that. I found that to be really a watershed moment for me playing bass.”

This year marks 55 years since the release of Jefferson Airplane’s Surrealistic Pillow album, which spawned the classics Somebody to Love and White Rabbit. What do you recall about its recording?

“That was recorded right down from me at the RCA Recording Studios, and we lived up in San Francisco then, so we would fly down to do a project.

“I think the first album was four days, the second album – Surrealistic Pillow – was two weeks. The first album was a three-track, and you had one track to bounce, and basically walked in there, played the material we played on stage and played it as a set.

“Surrealistic Pillow was the beginning of the four-track. So, just like the Beatles used it for multiple overlaying and whatnot, you had a lot more choices. That was part of the excitement of the time – having the latest/advanced equipment.

“At the same time, recording Surrealistic Pillow and all the tracks on there was really a special time. I remember it being a two-week period where you just submerged yourself in the studio.

“Unlike the first album – where it had been material all worked out that we had played for quite a while live – the material for Surrealistic Pillow came in partially written, or we wrote it all on the spot.

“Those two songs [Somebody to Love and White Rabbit] had been played by Grace in the Great Society – but they were new songs to us. So, we took those songs apart and put them back together as we would play them.

“Somebody to Love was a great rock song, and I just remember for a bass player, playing in F# was a great key to play in – you would walk up to the F#. But I just remember trying to write a good bassline to try and carry that song along.

“With White Rabbit, I drew upon my classic listening background of Ravel and Bolero – instead of just the drums coming in at the beginning of that, I came in with the bass doing those quadruplets to start out the song.

“It just all fell together. It was exciting and easy, but everybody really lived in that time. You just immersed yourself in that music.”

- Hot Tuna tour the US through November/December and into 2023 – all upcoming dates are on their official website .

Greg is a contributing writer at Guitar World. He has written for other outlets over the years, and has been lucky to interview some of his favorite all-time guitarists and bassists: Tony Iommi, Ace Frehley, Adrian Belew, Andy Summers, East Bay Ray, Billy Corgan, Alex Lifeson, Geddy Lee, Les Claypool, and Mike Watt, among others (and even took lessons from John Petrucci back in the summer of ’91!). He is the author of such books as Grunge Is Dead: The Oral History of Seattle Rock Music, Shredders: The Oral History of Speed Guitar (And More) and Touched by Magic: The Tommy Bolin Story.

“It holds its own purely as a playable guitar. It’s really cool for the traveling musician – you can bring it on a flight and it fits beneath the seat”: Why Steve Stevens put his name to a foldable guitar

“Finely tuned instruments with effortless playability and one of the best vibratos there is”: PRS Standard 24 Satin and S2 Standard 24 Satin review