Jack Bruce: “Jimi Hendrix regarded the guitar as an extension of himself. But in an instrumental sense, I would argue that Eric Clapton was probably better”

In this classic 2003 interview, the pioneering bass guitarist and rock legend talks Cream, explains why Clapton was better than Hendrix and confesses his love for gangsta rap

In the late '50s and early '60s, the bass guitar was a simpler, safer beast. You listened to your guitarist and plunked away at your root notes, taking care not to step on the drummer’s toes, of course.

That was just the way it was, and that was the way it would always be – that is, until the bass guitar’s role was changed forever by a small group of pioneering players, including Paul McCartney and the late John Entwistle. And, of course, Jack Bruce.

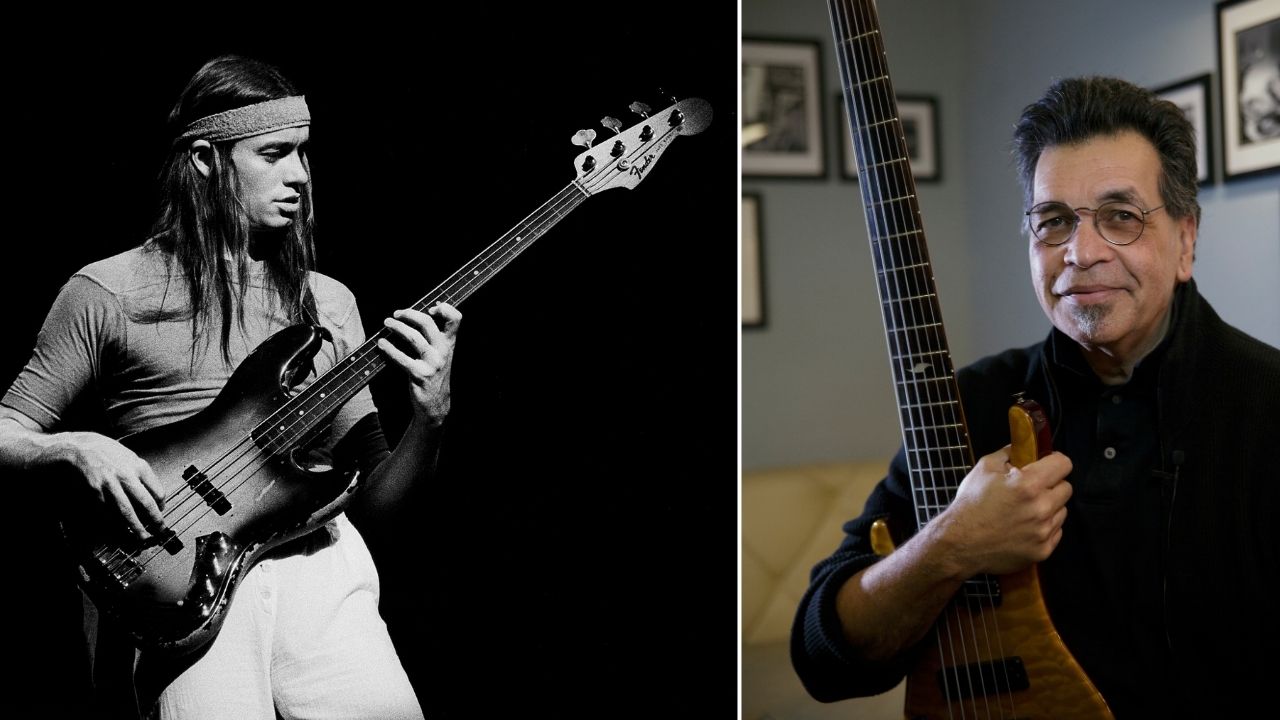

Born in Lanarkshire, Scotland, in 1943, Bruce brought an acute melodic awareness to the bass guitar from the moment he picked one up.

By the time he was 30 he was a veteran of Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated, the Graham Bond Organization – an incarnation of which featured the young John McLaughlin – John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, innumerable sessions and, of course, Cream, in which he created a mesmerizing, blues- and jazz-laced rock spectacle alongside drummer Ginger Baker and Eric Clapton.

After Cream split in 1968, Bruce released a string of solo albums that demonstrated his trademark blend of jazz, rock, blues, and – latterly – world and ethnic influences. He also participated in a number of high-profile tours in Ringo Starr’s band and elsewhere, and worked with Gary Moore and Ginger Baker in the BBM project.

In April and May 2003, Bruce’s solo albums Songs For A Tailor, Things We Like, Harmony Row, Out Of The Storm, How’s Tricks?, Jet Set Jewel, Jack Bruce And Friends Live At The Free Trade Hall, Manchester, and a compilation, An Introduction To Jack Bruce were reissued on CD, along with a Cream album, The BBC Sessions.

Bruce was on fine form when we spoke to him that year, and why not? He was in the autumn years of a life well lived.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Are you pleased with the reissues?

“Of course. It’s nice to have them out, but it’s especially nice to have Jet Set Jewel out at last because I never thought it would come out. I thought its time had come and gone. Basically it wasn’t a commercial enough album for what the suits wanted: Rob Stigwood was selling out to Polygram at the time, and I guess they wanted the Bee Gees.”

You obviously weren’t disco enough for them?

“Well, yes, although if you listen carefully there are some elements of pea-soup hi-hat in there. After that I parted ways with Stigwood, although I was stuck in limbo for two years – the old story of the record company saying, we don’t want to work with you, but we’re not going to let you work for anybody else! It was contractual, evil things.”

Jack Bruce And Friends Live is also previously unreleased.

“I’d forgotten all about that show being recorded. I think that was a pretty good example of that band. It’s very good playing, but obviously sound-wise it’s a little different to what I would have preferred. But there’s not much you can do about that.”

There’s also the Cream At The BBC CD.

“The BBC guys were great. With the limited equipment they had – and the people there were even more limited than most people! – they got a tremendously good sound, I think. They were only allowed to use a certain amount of recorded music, so you had to play live.”

There are interviews with Eric Clapton on there, but none by you.

“Well, I guess in those days Eric was the spokesman. It was like that, wasn’t it? They didn’t want us rowdy lot, it was all contrived and controlled. At that time Eric was the face of the band. I don’t mind.”

You attended 14 different schools as a child. One of them was the Royal Scottish Academy of Music, where you had won a scholarship for cello and composition. But you left, reportedly because you were discouraged by the professors’ lack of interest in your ideas.

“Well, yes. That sounds a bit arrogant, but then you are at that age. I got that scholarship when I was very young, I was 16, I think. I was still at school and going to the Academy part-time.

Charles Mingus was a big influence, as obviously he was a bass player and a great composer

“Some of it was great: I mean, the first harmony teacher was really good, but he was a complete Bach freak and he spent all his time looking for mistakes in Bach, like doubled major thirds and tritones and everything. And that was his life! Apart from that he liked to tap-dance on the bass pedals of the organ, so I wasn’t really learning a lot. Plus I’d discovered money and girls – more important things. Basically I was really interested in jazz, and they were so against it.

“Charles Mingus was a big influence, as obviously he was a bass player and a great composer. There were these practice rooms with really nice upright Steinway pianos, and I used to spend hours improvising, but they’d come in and tell me to stop. I played a Modern Jazz Quartet EP to this guy at the Academy, and he just sneered at it, you know.”

The classical training you received there must have been useful, though.

“It was in the early days. It’s nice to be able to write things. All those early songs are written down – even things like Cream’s White Room were actually scored.”

Did other bass players influence you?

“Yes, very much so, like Mingus and Charlie Haden. I saw Ray Brown very early on, although he wasn’t an influence. Percy Heath was the first bass player I saw live.”

In 1962 you joined Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated, with Charlie Watts on drums. I assume you and he made a good rhythm section?

“Oh yes, it was. I always liked Charlie’s playing. He hadn’t quite found his thing yet. He loves jazz, he worships it in a way, and I think he’s what you might call a gentleman drummer. He’s got a lovely backbeat.

“I think drummers like to play with me because I make them sound good. That is the function of the bass player. I remember going to a clinic that Billy Cobham was doing and someone asked him who his favorite bass player was.

“He didn’t know I was there, but he actually said ‘Jack Bruce’. I think the reason he gave was the rhythmic approach and the harmonic approach that I had picked things up in the right way.”

When did you switch from upright to electric bass?

“In about 1963, ’64. I always played upright with Alexis Korner. I got asked to do this Ernest Ranglin session and they said, we want bass guitar. So I borrowed one. It was an Epiphone semi-acoustic with black nylon strings, but for me it was great. I suddenly realized that I could play louder than the drums, so I immediately switched.”

You left your next band, the Graham Bond Organization, after three years because Ginger Baker said your playing was too busy. How did you feel about that at the time?

I was getting a lot of criticism, not just from Ginger, but from a lot of areas, for this melodic, so-called ‘busy’ approach, instead of playing four in the bar or something

“I almost gave up. I was very hurt by the whole thing. I thought I was doing some interesting things. But I was getting a lot of criticism, not just from Ginger, but from a lot of areas, for this melodic, so-called ‘busy’ approach, instead of playing four in the bar or something. I was influenced by James Jamerson, for instance – people like that.”

What was it you liked about Jamerson’s playing?

“Everything – the way he was playing melodies rather than just root notes. That kind of polyphonic idea appealed to me on the bass, as opposed to just a supporting role.”

I bet Ginger changed his tune as the years went by.

“I don’t know if he ever did, really. He probably still thinks I should be standing there going thump, thump.”

Was there generally a view back then that melodic bass was intrusive?

“Well, there weren’t many people doing what I was trying to do. It just hadn’t happened yet, so it was down to people like me to make it happen.”

Cream was my great opportunity for me to play too many notes and get away with it!

You turned down Marvin Gaye’s offer to join his band in America because you were about to get married. Do you ever wonder what it would have been like to play with Marvin?

“Of course. I wonder what might have happened, because much later on I became good friends with Jamerson. Marvin was very encouraging to me, to continue finding this style. But then, of course, Cream wouldn’t have happened, and that was my great opportunity for me to play too many notes and get away with it!”

Was it only with Cream that you were allowed to express yourself on the bass as much as you wanted?

“Well, I was always doing that, really. Obviously with Cream we were able to do that because it was a jamming-type band. Cream was like a jazz band, but we didn’t tell Eric that... we were like a little free-jazz trio with Eric as Ornette Coleman, but without him knowing it.”

You sometimes played a Fender VI.

“Yes. I started playing that with Graham Bond, because when John McLaughlin left it meant that I could do little guitar-type solos and stuff. It wasn’t really a very playable instrument because the strings were very close together for a bass, and the scale was too big for a guitarist. It was a kind of hybrid. I enjoyed it for a while, it was fun.”

What were your first impressions of Eric Clapton’s playing?

“He was so obviously ahead of everybody else at that time, with his approach and his knowledge of the blues. I also played with him briefly in John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers – he was just leaving when I joined. He was just going on his famous world tour, but he only made it as far as Greece and came back after he saw some meat hanging up with flies on it... That’s the story, anyway.”

You also played with Jimi Hendrix very early on in his career.

“I was the first guy to bring Jimi on stage. We’d heard of him through a friend who had claimed to have seen him play in New York. Cream was playing at – I think – St. Martin’s School Of Art, and I was having a pre-gig pint. This guy came up and said, ‘Hi, I’m Jimi Hendrix, can I sit in with your band?’ And I said, ‘Well, I dunno, let’s go and find out.’

“So we went across the road and Eric was very keen for him to play and Ginger, of course, was completely against it. But he did play, and he blew us all away, playing with his teeth and all that. Eric was stunned. There’s a demo that we did the next day, and you can tell in Eric’s playing that he’s trying to emulate some of that stuff.”

You talked with Hendrix about forming a band together. How close did this come to reality?

“That was actually going to happen. Jimi was all for having a play. At that point he was trying to find a new direction, musically, and that could easily have been it. I was all for it because I think one of the problems Jimi had was that he didn’t play with people who kicked him up the arse, basically.

“I’m not knocking Mitch Mitchell, but to me he was like a British jazz player, he was kind of laid-back. He played a lot of rhythms but I don’t think it pushed Jimi in the way that we would have.”

In an instrumental sense, I would argue that Eric was at least as good as Jimi, probably better

At their peak, which was the better trio – Cream or the Jimi Hendrix Experience?

“Certainly I would say that Cream were a more interesting band, although obviously we didn’t have Jimi. But I would say that Eric was a better guitar player. Obviously Jimi was Jimi, and he could have played the Indian nose flute and it wouldn’t have mattered, because he was playing himself – I think he regarded the guitar as an extension of himself. But in an instrumental sense, I would argue that Eric was at least as good as Jimi, probably better. I think Cream had something quite magical as a band when we were playing live.”

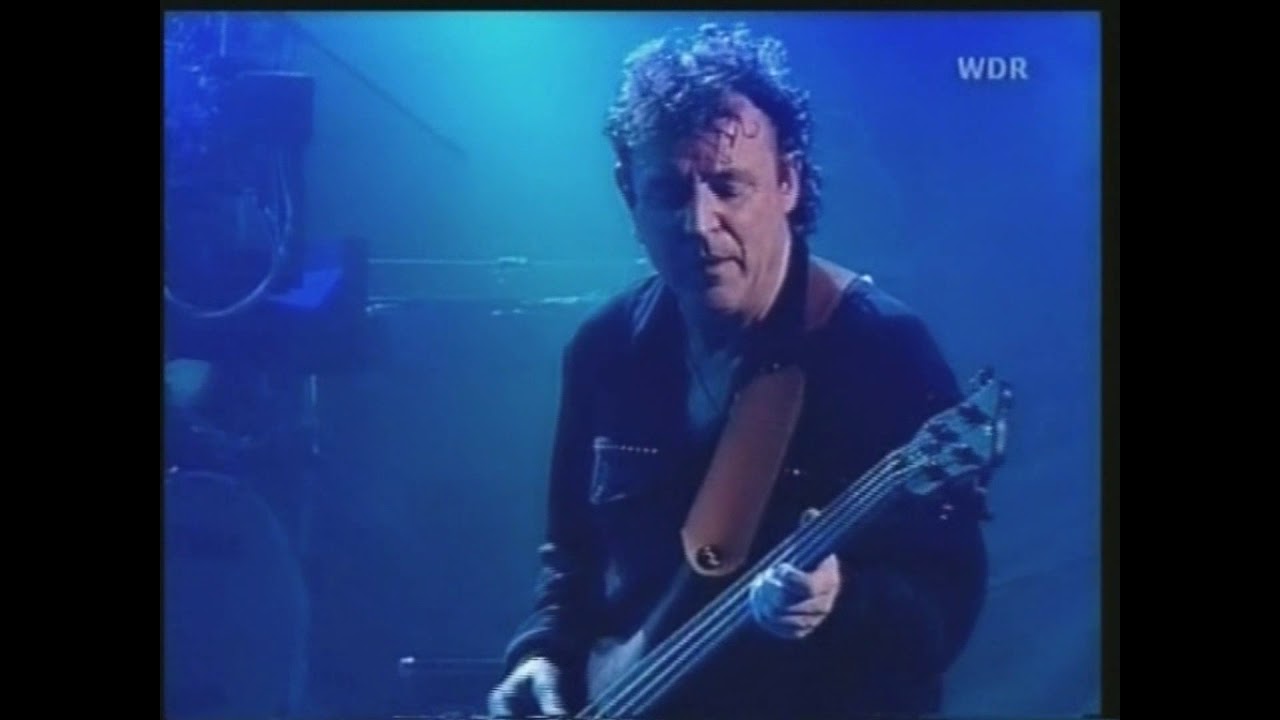

You described being in Lifetime, with John McLaughlin, as the musical time of your life. Why is that?

“It was the most challenging music, which I really enjoy. For instance, on one tune I’d be playing in E and singing in C, plus there were quite difficult things like polytonalities and so on, and it was rhythmically very advanced. So when that band gelled, there was nothing like it. People who saw it still tell me that. It was like Cream, but down the road a bit.”

From Songs For A Tailor onwards, you’ve combined rock, jazz and classical styles in your music, plus what we would call world music. Do you compose with a particular style in mind, or does it come out more organically?

“It just happens. The second album was written in one afternoon. The early ones were written almost as song cycles, although I hate to use these pretentious words. They were written in the order they came out on the record.”

I don’t think musicians ever really retire. You just fall off your perch.

Are you more of a rock player than, say, a jazz player?

“Yes, if you have to put labels on it, although I think I’ve managed to come up with a style of my own. My own thing, as it were. But since the '50s, when rock ’n’ roll and R&B started to influence things, I think you’ve been able to forge your own style. Especially if you play the music that you write, you’re not constrained by other people’s writing.”

I noticed you’ll be 60 this year.

“Aaagh! So did I. But I don’t think musicians ever really retire. You just fall off your perch.”

Far from slowing down, your career seems to have accelerated in the last few years.

“Yes. I had some time off a while back and just thought, 'Oh, I might as well do some work while I can.' I’m not touring so much this year, I’m finishing off my new record and then I’ve got some things later on.”

Is BBM finished now or is there any likelihood of a reunion?

“I think it would be a BM-something else! One of the Bs might not be there next time. That was a great band, but there were some problems with one of the Bs... I speak to Gary Moore a lot. The last thing we did was the Remembering John Lee Hooker record, which was fun. We’re always talking about doing an album together.”

Are you still playing fretless Warwicks?

“Yes, but more and more I’m using this old Gibson EB-1. God knows how old it is, I think it’s from the Fifties. It’s got this big, old-fashioned, woofy sound. I use that a little bit more, but my first love is still the Warwick fretless, and I’ve got loads of those.

“I do like them, it’s just that when I’m playing songs like With A Little Help From My Friends with Ringo Starr, it doesn’t sound quite right on a fretless. So the EB-1 is more of that period, plus it’s violin-shaped.”

Didn’t you suggest the extended upper horn to Warwick when they were designing the Thumb bass?

“Yes, because the balance was terrible. I bought one and I thought it was promising, so I helped them out. Normally I go for the bubinga and wenge woods and MEC pickups.”

Are you a five- and six-string bassist?

“Well, I’ve still got a Fender VI which they gave me, and a couple of five-string fretlesses, but I just don’t really see the point of a six-string for me. I like four strings: The limitations make you come up with ideas. If you’ve got all those notes, you can just play them. Obviously I’ll use a five-string if I want to tune down and go to a low C or something.”

Of all the basses you’ve ever owned, what was your favorite?

“I’m not a big collector, but I’ve got what is supposedly the eighth Fender bass ever made, with the Telecaster headstock. It has 0008 on it. It’s on my wall, and I occasionally play it, but I wouldn’t take it on the road or anything. It looks great, it’s got the original pickup.

“I’ve also got a really nice plexiglas fretless that Dan Armstrong made for me. I think there’s only one other, and Paul McCartney’s got it. But I think the Warwick Thumb that I’ve had for 10 years is my favorite, as well as the EB-3 that I played with Cream, which has a very thin, wide neck, the way I like it.”

The way I play the distortion comes from the fingers anyway. But I like the amps to be clean

What about amps?

“I use the Hartke stuff, I’ve been using those for years. I used to work with those guys too, to help them come up with idea of valves and transistors in the same setup. At the time I was using two amps, so we worked on making that happen.”

Do you prefer a clean sound or do you like a bit of overdrive?

“Well, the way I play the distortion comes from the fingers anyway. But I like the amps to be clean. In the old days, that wasn’t possible above a certain volume, although now I don’t play as loud as I used to.”

Any effects?

“No, I don’t use anything. When I’m recording I don’t even use an amp, I just stick it straight in. The tone controls are pretty flat too. I think pedals for bass just get in the way of the sound, although in the '70s I went through a period of using different things – choruses, phasers and so on.

“I had this one amazing little effects thing called an Effectron Junior, like a little digital delay thing. You could play a chord and then just stand twiddling knobs for five minutes and that was the solo!”

I think pedals for bass just get in the way of the sound

Did you ever play slap bass?

“No, I never thought it was for me. I kind of fooled around with it but I just thought, it’s not me. I’m glad I didn’t get into it. I remember in the '80s it was the done thing and everybody was doing it. There were a few good people like Larry Graham and Mark King. I liked the way Mark was doing it, but not all those people who did it just because you had to do it. It never struck me as being that great.”

What current music are you listening to?

“My kids introduced me to gangsta rap, so I’m pretty up on that. Missy Elliott does a lot for me, she’s a poet. I used to like Cypress Hill a lot, I thought they were fantastic. I thought they were like the Beatles, they had all that musicality and all that humor. Anything original and not too serious, I like.”

My kids introduced me to gangsta rap, so I’m pretty up on that. I used to like Cypress Hill a lot, I thought they were fantastic. I thought they were like the Beatles

I’d like to hear your thoughts on John Entwistle.

“He was great. Loud! Very loud. He was an unusual sort of a player, he had his own thing going.”

Bootsy Collins?

“He’s a great guy, he’s a lot of fun.”

“I knew him a little bit, as much as anybody could at that point. It was towards the end when I knew him, and he was in a bit of a state. The sound that he had, you watch a TV show now and there’s loads of guys doing it.”

Flea?

“I’ve got a lot of time for him, especially his backflips. He does them better than me.”

Joel McIver was the Editor of Bass Player magazine from 2018 to 2022, having spent six years before that editing Bass Guitar magazine. A journalist with 25 years' experience in the music field, he's also the author of 35 books, a couple of bestsellers among them. He regularly appears on podcasts, radio and TV.