Interview: Steve Hackett on His New Album, 'Beyond the Shrouded Horizon'

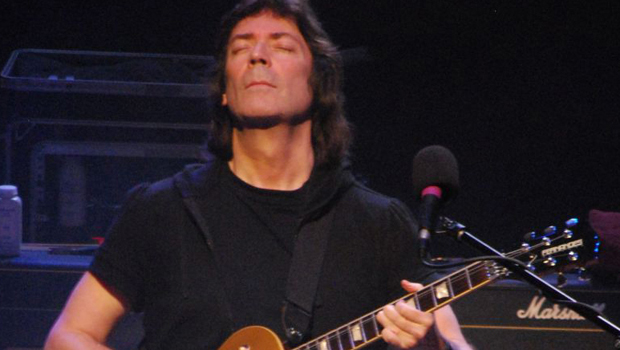

Steve Hackett stamped his impression on the guitar community when he joined Genesis in 1970.

Reserved as he was during those first few performances, Hackett quickly assumed the role as one of the country’s most innovative guitarists, pioneering the tapping and sweeping techniques — techniques that are now part of every ax chopper’s lexicon.

Last year Hackett was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame for his work with Genesis during what the rock community likes to refer to as its Golden Age.

Post-Genesis, Hackett put out one album with the short-lived supergroup GTR, 24 solo studio albums and a handful of live albums. Throughout his career, he’s continued to stretch his craft. Although Hackett is widely recognized as a major player of progressive rock, Bay of Kings (1983) and Momentum (1988) both showcased Steve’s mastery at the classical guitar. Blues with a Feeling (1995) stretched him even further when he explored blues.

Beyond the Shrouded Horizon is set to release September 27, and, although Hackett says he didn’t set out to assemble an all-star cast, that’s exactly what happened, and he’s lucky. Chris Squire of Yes, Nick Beggs of Kajagoogoo and solo artist Amanda Lehmann are among the names that appear on the album. Hackett says they’re all virtuoso performers, and he’s excited that they could all come together on this project. GuitarWorld.com is streaming a song from the new album, "A Place Called Freedom," right here.

GUITAR WORLD: In another interview, you refer to Jimi Hendrix as “riding the storm.” What’d you mean by that?

I was referring to his ability to play through feedback. It’s no easy thing — when you’re a guitarist — to play through feedback, to “ride that storm” in a sense. I remember him doing that live. I saw his last big show at the Isle of Wight Festival, and indeed when he was playing — specifically when he was playing “All Along the Watchtower” — and it’s raining, you know, it’s a very wet night — I remember there was this sense of sport at that time, that — and what he was doing as a musician — they seemed to be one. It was dangerous. He was trying to make himself play through it.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

I’ve seen that gig that he did on video, and you can tell he’s having a hard time. But then there we are in the midst of not wanting him to turn it down. The whole idea of Hendrix’s approach was astounding, which was one where he didn’t let professionalism get in the way of taking risk. No matter how big the audience, he wasn’t afraid to improvise. Walking that tightrope. He never separated the idea that you should be up there enjoying yourself or discovering things, even if you’re playing a professional show. It didn’t seem to be an issue for him.

Are you ever afraid of letting professionalism get in the way?

All the time. Then I did quite a bit of shows where I realized that a lot of performance is improvisation. Even if you adhere to form quite strictly, I think the spirit is the most important thing at the end of the day.

On your website, you mentioned that the new album is a sequel to Out of the Tunnel’s Mouth. How so? Did you know that going into it?

I did, because all of the material was recorded at the same time, in parallel. I wasn’t able to finish those pieces at the time. So it’s a bit like working on separate canvases at the same time. Also, I had other things going on in my life — litigations, contesting the rights of some of those tracks. I’d put some of them to the side. I didn’t like the idea of the band not being attached to it.

Of the album, you also said, “It’s not just about the romantic places, but the people that inhabit those places.” Tell me about some of those places. Are they real? Based on reality? I remember reading you mentioning a song inspired by Jack Kerouac’s “On the Road.”

Yeah, that would be the "On the Road" song, “Prairie Angel." That was inspired by a farmer’s daughter. A young man and his buddies agree to chasing this most beautiful woman they’ve ever seen in their lives. And yet nothing happens. Everything is unspoken because it’s amidst this vast landscape of the plains. It’s one of those things we only dream of over here — the stuff of John Wayne movies. In a sense it’s imaginary pioneering, taking this pioneer encounter in the midst of all of that and in the way she symbolizes the land and some of those elements. The song is very much influenced by Americana.

After 24 albums, does it still feel fresh?

It does. I still get a thrill out of making music. I also get a thrill out of making it right. I don’t have too much time, because the clock is ticking, I suspect. I don’t mess around with the things I don’t love. I jump in with two feet these days. I’m thinking of the guitar work on “The Phoenix Flown." Recently I saw — at a Joe Bonamassa show — and then when I was talking to him — during playing — he played one of my tunes, “Los Endos” from way back. He was very much Joe, who plays blues guitar, but he played with this sort of commitment, and he brought a freshness to it, even though we’ve all heard changes in blues guitar at the time. It’s what the solo does within that landscape, within that fixed perimeter.

So when I was playing this part on “The Phoenix Flown,” I was thinking of a tone that he had at one point where he played a bit fast but within that played slowly and a bit sweeter with an upper harmonic on it and a bit of reverb and I thought, I recognize myself in these sounds, where the guitar starts to walk and get a little more fiery, where it’s a little more voice-like. Lots of guitarists are always trying to chase “the woman’s voice.” It’s where you go, “That note — that could be a voice.” I sometimes hear it from a distance, and I realize that could be an opera, where someone’s in the next room calling you. I look for the soprano.

So you hear the woman’s voice too?

I hear the voice in the guitar. And I definitely hear the guitar in the voice these days, yes.

You’re said to have pioneered the tapping and sweeping technique. How does that feel?

In 1971, on my first Genesis album, Nursery Cryme, I used tapping extensively. You can hear it all over the album. And Eddie Van Halen graciously credited that album with being an influence. By my third album with Genesis — their fifth — the first track has both tapping and sweep picking on it, which I’m also credited with inventing. That’s 1973. I can’t help it if I invented those things; I did. Those things which are part of the vocabulary of every shredder out there. And I credit both of those happenings to Bach, because I tried to play things on one string. I started tapping when I was trying to play a Bach line on one string. And sweep picking was really a bowing technique on the violin where you’re going backwards and forwards very quickly. So it borrows from far back.

So you were hunting for a sound you weren’t sure you could get.

I didn’t think I could get that. I didn’t know if it would work, or if I was capable of playing entire lines like that. At shows, I was always afraid of playing slightly ahead of the beat. I was always speeding up. And that can become a problem, of course. But I found that you could play phenomenally fast, so for a short time I would play that way. But I would say that diversity was more of my calling card more than speed. And I’m anxious to play many things, going for that operatic guitar sound. And so I like when you can play really fast — you can make it sound like a piccolo line. It’s another way of looking at speed. Is that a keyboard? Is that a wind instrument? I’m also interested when instruments start to impersonate each other.

Do you have a favorite technique?

I try not to make a distinction between playing guitar and singing. How can I put it? I don’t want the guitar to be a poor second cousin to the keyboard. There are times when you think you might be listening to the keyboard. It was common with the guys in Genesis. We had guitarists who were trying to sound like keyboard players and keyboard players who were trying to sound like guitarists. Sometimes a third instrument, a third sound gets born from it.

Would you say that you’ve decided to write music around the guitar?

Oh, certainly. I think that’s a good way of looking at it. I would say I don’t want to be limited to what the guitar can do. I think the guitar is unlimited as an instrument. It has a certain sound. And that’s why we love the guitar. The electric can impersonate brass and the voice and at time the violin. Then there’s the twelve string where it can sound like a cross between the harpsichord and the bells. And then the classical guitar, with the nylon strings, you can definitely hear the harpsichord. And with the electric — it’s phenomenal — hearing anything from a scream to a whisper.

The guitar is an incredible instrument. With the keyboard, I guess you can access more harmonies in one go, but I think the secret is to make people feel that limitless stretch. One of the reasons why I favor the guitar so much is that with the different tuning you can make so much. You can give the harp a run for its money.

You’ve been all over the world. What city or experience has influenced your guitar playing the most?

I’m influenced by everything, everywhere. My bags are permanently packed, so I’m always gathering influence. I’m influenced by everything from Americana to Victoriana. From Indian music to the music in Hungary and Germany and Gypsy music. And I also am heavily influenced when guitar gets bright blow. I’m thinking of Muddy Waters now.

Do you have memory of seeing one guitarist that truly inspired you?

Yeah, I remember seeing Andres Segovia on TV. And I’m watching his fingers, and there are all these notes coming out, but his hand hardly seems to be moving at all. And I found that absolutely thrilling. He was playing a Bach piece. I discovered many years later that the piece was written for the violin. So whether you’re caressing the guitar as Segovia did or shredding it, it’s the most adaptable instrument you’ll ever be able to get your hands on.

Steve Hackett's new album, Beyond the Shrouded Horizon, will come out via Inside Out Music on September 27. Pre-orders signed by Hackett are available now from HACKETTSONGS WEBSTORE.