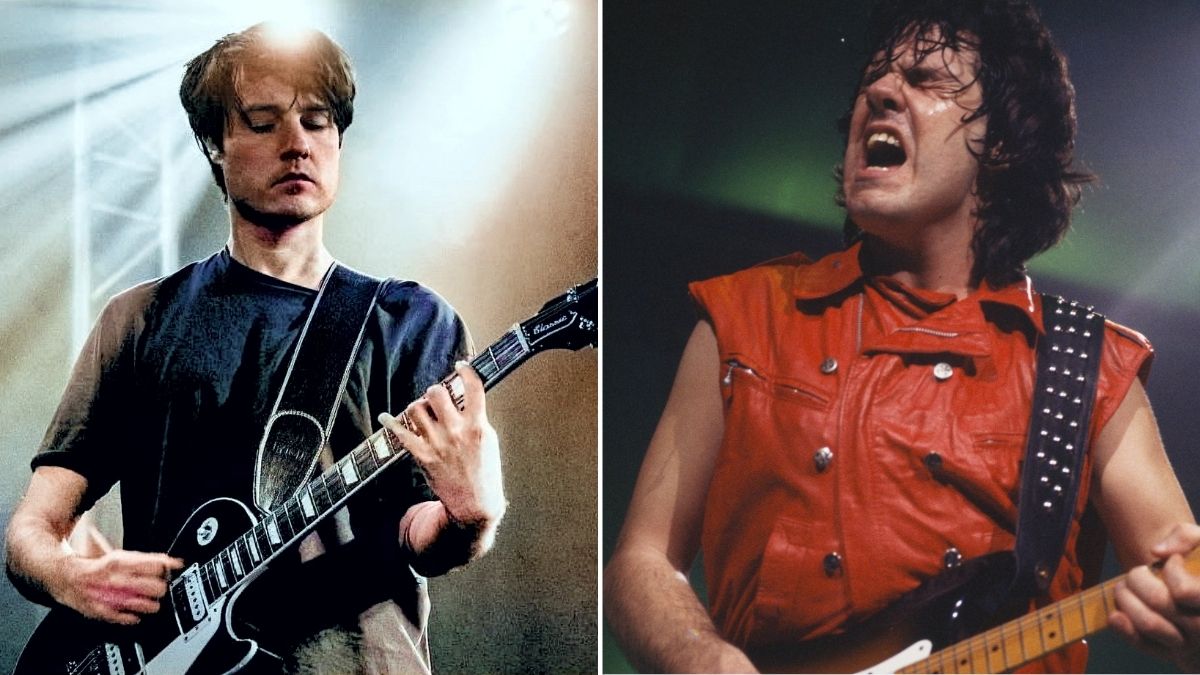

Interview: Soundgarden's Kim Thayil on Alternate Tunings, 'King Animal' and More

When the members of Soundgarden—singer and guitarist Chris Cornell, guitarist Kim Thayil, bassist Ben Shepherd and drummer Matt Cameron—reunited in 2010 after more than a decade apart, making a new album was the last thing on anyone’s mind. According to Thayil, the band reconvened only to address some outstanding business matters. But musical connections can have a powerful allure. Within a short time, they picked up their instruments and began booking scattered live dates, including a headlining appearance at 2010’s Lollapalooza and, the following year, a full-scale summer shed tour.

As it turns out, the live shows were only a harbinger of bigger things to come. Says Thayil, “If you get the four of us in a room together, we’re not just going to whip out ‘Outshined.’ We’re more inclined to plug in and start pulling out some new riffs.”

The result of that inclination is the new King Animal, Soundgarden’s first album of new material in 16 years and a worthy addition to the band’s storied catalog. Indeed, all the characteristics that contributed to establishing Soundgarden as one of the most successful and forward-thinking hard rock acts of the Nineties are firmly in evidence on the new record: Pile-driving riffs juxtaposed against jerky, odd-metered rhythms; finely honed melodies that are dirtied up with all manner of guitar dissonance, feedback and squeals; the use of unorthodox alternate tunings to conjure atypical melodies and tonal colors; and, of course, Cornell’s distinctive feral wail.

That the band was able to seemingly pick up right where it left off doesn’t appear to surprise the now 52-year-old Thayil. “For the most part when I write songs I’m thinking, What would Chris’ voice sound like on this? What would Matt play on the drums? What would Ben do?” he says. “And I think the other guys feel the same way. We all envision and are very aware of each other’s styles and think about the band collectively when we’re writing.”

And so while in the leadoff track, “Been Away Too Long,” Cornell sings, “You can’t go home,” Soundgarden appear to have found their way back. “The whole thing started as a business concern, then moved to a performing thing and, finally, to us being a creative unit again,” Thayil says. “Which has been really great.”

The guitarist recently sat down with Guitar World to talk about how King Animal came to be. He also took time to consider Soundgarden’s trailblazing history, discuss the gear that has helped to shape his distinctive sound and reveal just what he’d been doing all those years when the band was broken up.

Soundgarden have been back together for a few years now, but it wasn’t until recently that there was talk of recording new material.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

I think when we first got back together the interest was only in attending to aspects of our legacy—things like merchandising, our online presence—that didn’t exist. And there were some legal and financial issues we had to address as a partnership. In the time since the band had split in 1997, there had been quite a change in the music industry. Our record company, A&M, was bought by Universal and was pretty much turned into a back-catalog label. Our management was downsized, and became, like, a voicemail and a P.O. box. And the band was broken up. So there was no label, no management and no band to pay attention to any of our affairs.

You reformed in order to change that?

We wanted to work things out. I think it was in January 2010 that we restarted our fan club, put up a web page and began to develop a web site. We were working on merchandising deals for T-shirts and posters and some of our records, and making them available online. Then we started in on the social media stuff. Because we had no e-presence. And all the rumors and interest that was generated from that led to offers for us to play live. So it was just a matter of time before we got in a room together to jam. And that was fun. It went well. So it was, “Let’s play a show.” We did a few shows and then we played Lollapalooza. And through performing and rehearsing, we naturally jammed and improvised and introduced riffs and ideas to one other. That stimulated the interest in writing and recording together. And now here we are.

A stylistic hallmark of Soundgarden’s music—and one that is very much present in the new material—has always been the band’s tendency to write and play in altered tunings. Where did that interest initially stem from?

Well, the whole drop-D tuning thing was probably popularized in Seattle as a consequence of our success. And we couldn’t be stagnant and just stay there, so we started playing around with other tunings. We liked the fact that what we were playing didn’t sound like what our friends and peers were playing. So we started introducing things like open slide tunings into our songs. Then we had what we called the “digga digga” tuning, which was drop-D with the A string dropped to G. That really took off for us around [1991’s] Badmotorfinger. And also the [low to high] E E B B B B tuning that Chris and Ben used on [1994’s] Superunknown. [This tuning can be heard on Superunknown cuts like “My Wave” and “The Day I Tried to Live.”]

I recall that the song “Mind Riot” from Badmotorfinger was recorded with all six strings tuned to varying octaves of E.

Chris came up with that. And I believe it came from a conversation he had with [Pearl Jam bassist] Jeff Ament. Jeff said to Chris, “Hey man, wouldn’t it be crazy if someone did a song where every string was tuned to E?” Well, that wasn’t a completely uncommon tuning. It was done well before us. But Chris was like, “That would be weird!” And he came up with “Mind Riot.” But I think Jeff had said it as a joke.

You mentioned earlier that you felt the drop-D tuning that was so prevalent in grunge music came from you guys.

Well, there weren’t a lot of bands doing the drop-D thing properly. That all kind of came from us. Because, in the beginning, the big Seattle bands were probably us and Green River, and then Mother Love Bone. The fact that Alice in Chains and Nirvana started using it was because we used it.

How did you come to discover the tuning?

There was a conversation between me, [Melvins singer and guitarist] Buzz Osborne and [Green River singer and future Mudhoney frontman] Mark Arm in Mark’s apartment in the U District [the University District in Seattle] in ’85 or ’86. We were just sitting around listening to records, and Buzz was telling us about Black Sabbath. He said, “Hey, you know on this song Tony Iommi uses this tuning where he tunes his E string down to D.” And we were all like, “Really?” All I knew of altered tunings back then was slide guitar tunings, like what the country guys used. And I knew Sonic Youth was experimenting with a lot of tunings. I was not aware of the Melvins using drop-D, but I’m sure they were.

But what I was most aware of was Buzz letting Mark and me know that Sabbath did it. So I went and started playing around with that. And I wrote the song “Nothing to Say,” and Chris wrote “Beyond the Wheel,” and we became married to that tuning. I remember that the Alice in Chains guys at the time were more like a glam-metal boogie band, and one day I ran into Jerry [Cantrell] at a D.O.A. concert, and he says to me, “Man, I love that song ‘Nothing to Say.’ What are you doing there?” And I told him, “Well, it’s in drop-D tuning.” And Alice in Chains became a different band almost overnight!

Another trademark of your guitar approach is your use of feedback and squalls as melodic and lead devices. You can hear it on songs like Badmotorfinger’s “Jesus Christ Pose” or, on the new album, “A Thousand Days Before.”

From our earliest days we were known as a band that would leave a lot of space for squealing and humming. Our very first recording was “Tears to Forget,” which appeared on the Deep Six compilation album. I remember that at the end of the session we had an extra track left, and so I did a whole track of just feedback from beginning to end. Then we mixed it into the song. And that was unheard of at the time, at least among us guys. I remember people saying, “They wasted a whole fucking track with Kim just fucking around!” Then when we rerecorded the song for Sub Pop [for 1987’s Screaming Life EP] we did the same thing. [laughs]

In general though, my sound is largely a result of the guitar I play, the Guild S-100, which I’ve been using since I was 18. It’s very microphonic. If you pick beneath the bridge or above the nut, the sounds are quite loud acoustically. That facilitates making weird noises. And I couple that with a few pedals. In the early days it was usually wah and chorus, but now I’m using delay a little more. On the new album I had a T-Rex delay pedal, and you can hear it on things like “Worse Dreams” and the intro to “By Crooked Steps.” So those effects help to accentuate and augment the kind of squeals I get from the Guild.

Is the Guild still your main guitar today?

Yes. Though on the new album I also used a couple of [Gibson] ES-335s. One in particular was a Trini Lopez that belonged to [King Animal producer] Adam Kasper. Like the Guild, that guitar has a long space between the bridge and the tailpiece where the strings can resonate pretty well. And you can also play behind the nut, so you can get a lot of weird sounds. And it’s semihollow, so it’s also sensitive to feedback. For amps, I was using mostly the Mesa/Boogie Electra Dyne. I also had a Mesa combo, a Tremoverb, I think, that belonged to Matt [Cameron].

Your partnership with Chris Cornell stretches back more than a quarter century. What was it that first attracted you to him?

I think it was how easily we wrote together, though back at the beginning of Soundgarden he was mostly writing on drums. But Chris, [original Soundgarden bassist] Hiro [Yamamoto] and I found it really easy to rehearse for a few hours and come up with a whole handful of ideas and at least one new song. We were able to be prolific. In all my previous bands I had been the primary songwriter, but in this band it was definitely very collaborative, at least initially. The collaborative nature kind of diminished after Hiro left, though we still write in different combinations. That leads to songs like “Jesus Christ Pose” or, on the new album, “By Crooked Steps.”

During the years that Soundgarden was inactive, Chris formed Audioslave and released a few solo albums, and Matt joined Pearl Jam. You kept a pretty low profile.

Are you asking what was I doing all that time? I considered myself semi-retired. I liked reclaiming my life. Because I didn’t need the money; I still don’t need the money. I like being creative, but I didn’t want to have to worry about publishing. I didn’t want to deal with contracts and managers and lawyers and accountants. And once you say, “Kim Thayil’s making a record,” it becomes, “We need a contract, we need a lawyer, we need a manager. And hey, what about a tour?” So I was like, “You know, I’m just gonna go have fun with my friends. I’m going to play music recreationally.” And every once in a while I’d go in and record on a friend’s project or help out a producer like Adam Kasper or Steve Fiske. Whenever Steve does a Pigeonhead record, I’m there. When Adam Kasper was working on the Probot record [with Dave Grohl], I came in. That’s fun for me. There are no expectations, and I’m able to just live my life and not be “rock star guy.”

But then after a few years of that I did start to think, Shit man. All those damn solo records you were talking about making! You ever actually gonna record those? [laughs] Now we’ll have to wait and see.

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.

“I heard the Money solo and thought, ‘This is amazing!’ So I sent David a telegram saying, ‘Remember me? I'm in a band now called Roxy Music’”: Phil Manzanera on his friendship with David Gilmour, and the key to the Pink Floyd man's unmistakable tone

“It’s really quite genius, but also hard to learn – it sounds insane, but sometimes the easiest songs still get me nervous”: Kiki Wong reveals the Smashing Pumpkins song she had the most trouble with