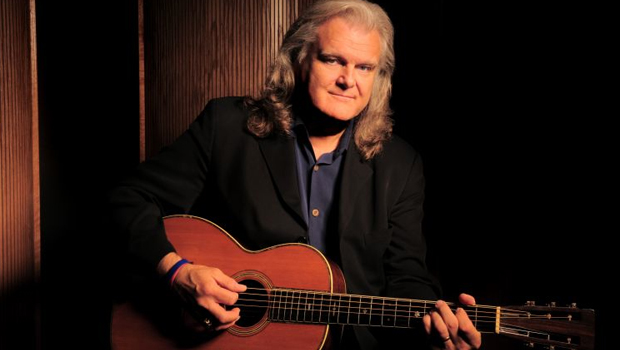

Interview: Ricky Skaggs Discusses New Album, 'Music To My Ears,' and Working with Jack White

In 1997, Ricky Skaggs launched Skaggs Family Records and created an in-house organization, including his recording studio, Skaggs Place, in order to take full control of his career.

As he explained during the keynote address at the 2009 Nashville Recording Workshop, there he could make records without "having 15 people sitting around a table telling me why bluegrass won't sell."

At the time, this was considered a bold step, particularly in Nashville. The record industry was still in full force, radio stations had not relinquished all of their independence to corporate giants, and the Internet had not upturned the ownership and distribution paradigm.

Skaggs, a 14-time Grammy winner, has been making music for more than 50 years. With his band, Kentucky Thunder, he strives to keep bluegrass in the forefront and continues bringing new fans to the genre, which also gives him something of a “hipness factor” across the musical spectrum. Mention bluegrass to rock, country and blues enthusiasts, and they all know Skaggs’ name.

His latest album, Music to My Ears, was released in the fall of 2012, around the time he was inducted into the Gospel Music Hall of Fame and was given the Academy of Country Music (ACM) Pioneer award. In this interview, Skaggs discusses his love for bluegrass music and his dedication to carrying its torch.

GUITAR WORLD: When you describe having one foot in the present and one in the past, how big a part does that play in the fact that your passion for this music continues to grow?

I’ve always tried to see it bigger than what a lot of people see. I see it as being accepted in so many other genres. Having Barry Gibb on this record [on the track “Solder’s Son”], having him play with me at the Ryman on Bluegrass Night and seeing how he got three standing ovations — and that’s where, when someone comes out with electric bass or piano or drums, there’s certain people that will get up and walk out of those shows; we’ve seen it happen — it’s pretty amazing to see that bluegrass is really loved, cherished and admired in so many other genres of music. That’s what keeps me excited about it, to see how many different people we can take this music to.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

When Jack White called and wanted me to do a video and play mandolin with The Raconteurs, I didn’t know anything about The Raconteurs at that time. I knew Jack, I knew the White Stripes, I knew the music that they had made, but when I started listening to what they did, I could hear the fact that they wanted to do a bluegrass version of a song called “Old Enough.” When I got down there, I didn’t know exactly what I was going to run into, but it was a fun thing.

I try to keep my heart and myself available for those little, “God moments,” are what I call them, where someone calls the office and says, “Would Ricky be interested in doing this?” Some things work and probably some wouldn’t, but certainly the thing with Barry Gibb has, and Bruce Hornsby when he and I did a record together and went out and toured it [Ricky Skaggs & Bruce Hornsby, 2007].

Great music is great music, period. It doesn’t matter if you stick the name bluegrass on it. I think people call things bluegrass that I wouldn’t necessarily call bluegrass, but what they’re calling country music today I’m not sure that I would call country music. But I love music and I try to encourage people.

I used to be a whole lot more fuddy-duddy stick in the mud about, “Well, this ain’t bluegrass and that ain’t bluegrass,” because people were coming up to me in the ’80s when I was having country hits like “Don’t Get Above Your Raising” and “Highway 40 Blues,” things that we were pulling from bluegrass, and they’d say, “Oh man, I love that bluegrass you’re doing.” I’d say, “Well, that’s not really bluegrass. Real bluegrass …” and then I’d tell them “Stanley Brothers, Flatt and Scruggs, Bill Monroe, people like that, that’s real bluegrass.”

I’m not so much that way anymore. When people say that, I say, “Thanks, I appreciate that,” because if you trim all the fat off of it and get to the meat of what I’m about, you’ll hear my roots, and they’ve always been bluegrass and old-time mountain music and gospel. They’ve always had those foundation stones that were laid in my life as a kid. That’s what I’ve built everything on with my music. It all stems from that.

There was a time when we could turn on the radio and hear those foundations — country, R&B and rock — on the same station. We got that education, and we didn’t think so much, Is this country or not? Now, people listen to stations that play one genre of music all day, or even one artist. Do you believe this underestimates the audience and what they might like if given a chance to hear it?

I do. I absolutely do. If you look at what the young kids are doing, they may not download all of my new record. They’ll go to iTunes and listen and they may not like “You Can’t Hurt Ham” because they don’t know the story of Bill Monroe that Gordon Kennedy and I told in the song, but they may hear “Music To My Ears” or the Barry Gibb song, like that, and download that and maybe one more thing for 99 cents. Then they may download a song or two from Joe Walsh’s new record, and who knows what else. That’s what they have on their iPhones — a mix of Skaggs and Clapton and Jeff Beck and whoever.

I think that the label heads on Music Row have had to create certain titles so they know how to market it and what to go after. But look at a new group like The Band Perry. They all grew up in East Tennessee, went to East Tennessee State, graduated from the bluegrass school up there and now they’re country stars opening for Alan Jackson and Keith Urban. There’s another group called Edens Edge and they all grew up on gospel music, loving The Whites, and now they’re making it as country. They’re not singing old-time traditional bluegrass tunes. They’ve taken that as a foundation, like what I’ve done, and they’ve built on that.

So I do agree with you. I think the label heads and people in the industry have shot themselves in the foot many times because they sell short the impact that bluegrass and real traditional country music have had on the whole world of music. When you see someone like Keith Richards that idolizes George Jones — I saw them come together. I worked on The Bradley Barn Sessions [1994] and Keith was so nervous before George Jones came in.

Keith got there about 10 in the morning and George didn’t get there until 11 or 11:30. Keith was shaking like a leaf on a tree because he was going to meet his idol that he’d listened to all his life. I know how people are affected by greatness, and when you hear George Jones, that’s greatness, there’s no doubt about it. Keith Richards, that’s greatness, what he does, the guitar he plays with the Stones, there’s nobody that could have done what he’s done. There are probably people that would shake like a leaf at the chance to meet him, but we’re talking about country music here and its influence and impact and how people are affected by people in country music.

Gordon Kennedy helped co-produce this album, Brent King engineered, and Lee Groitzsch is your studio manager. They are your longtime colleagues. How has that working relationship grown?

It’s just grown and grown. I trust these guys incredibly. This is the first time Sharon and I had an opportunity — the dates came in kind of quick, because normally we book six months out or even longer, sometimes a year out with fairs and stuff like that, but there was this music festival on the big island of Hawaii and they called my booking agent, made a deal and flew us over.

They said, “Oh, by the way, the resort would love to put Mr. Skaggs up for five nights on the house with his wife.” I said, “Sharon, what an opportunity! Let’s go! Let’s get away!” It was kind of a bad time to go because I knew I had a deadline to meet on July 20 for the album. But this was toward the end of June, so we decided that we were going to go. They paid for five days, we paid for two more, stayed a whole week and just had a ball. We had more rest on this trip than we’ve ever had on any vacation ever and we just loved it.

While I was gone I told the boys, “I can’t be gone 10 days out of the studio, so you’re going to have to do some work for me.” I had Brent take some vocal tracks that I had sung. I had sung six or eight songs, and I usually give him three or four tracks to choose from.

Normally I would sit down and choose my own vocals, but Brent went through them and put them together, and when I came back and listened to them I didn’t have to change one word. That was something that he did for me this time that I normally would do myself, and that comes with trust. Gordon did some overdubs on the Barry Gibb song while I was gone. He played electric guitar, did a couple of tracks, I got back home and everything was fine. Why did I have to be here? I didn’t have to worry about anything!

I guess in the past I've always been so … I don’t know if it’s controlling, or I’ve just been involved in my music from start to finish. This time I relinquished a little of my control and allowed some of the other guys to rise to the occasion and do more than engineer.

They helped in some of the production as well. It is great to have lifelong — I say “lifelong” because they feel like lifelong — Brent and Lee have engineered probably my last 10 records, maybe more, and Gordon has been here since Mosaic [2010], he’s come along and been involved in pretty much everything I’ve done. I love working with him. He’s a great musician, a great singer, great guitar player, has great ears, and I really like making music with him. It’s a great thing to have people you can trust.

Read more of this Ricky Skaggs interview here.

Alison Richter interviews artists, producers, engineers and other music industry professionals for print and online publications. Read more of her interviews right here.

Alison Richter is a seasoned journalist who interviews musicians, producers, engineers, and other industry professionals, and covers mental health issues for GuitarWorld.com. Writing credits include a wide range of publications, including GuitarWorld.com, MusicRadar.com, Bass Player, TNAG Connoisseur, Reverb, Music Industry News, Acoustic, Drummer, Guitar.com, Gearphoria, She Shreds, Guitar Girl, and Collectible Guitar.

“A virtuoso beyond virtuosos”: Matteo Mancuso has become one of the hottest guitar talents on the planet – now he’s finally announced his first headline US tour

“His songs are timeless, you can’t tell if they were written in the 1400s or now”: Michael Hurley, guitarist and singer/songwriter known as the ‘Godfather of freak folk,’ dies at 83